CHIANG SHIH-CH'uan a CH'ing DYNASTY POET-PLAYWRIGHT By

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Kūnqǔ in Practice: a Case Study

KŪNQǓ IN PRACTICE: A CASE STUDY A DISSERTATION SUBMITTED TO THE GRADUATE DIVISION OF THE UNIVERSITY OF HAWAI‘I AT MĀNOA IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY IN THEATRE OCTOBER 2019 By Ju-Hua Wei Dissertation Committee: Elizabeth A. Wichmann-Walczak, Chairperson Lurana Donnels O’Malley Kirstin A. Pauka Cathryn H. Clayton Shana J. Brown Keywords: kunqu, kunju, opera, performance, text, music, creation, practice, Wei Liangfu © 2019, Ju-Hua Wei ii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I wish to express my gratitude to the individuals who helped me in completion of my dissertation and on my journey of exploring the world of theatre and music: Shén Fúqìng 沈福庆 (1933-2013), for being a thoughtful teacher and a father figure. He taught me the spirit of jīngjù and demonstrated the ultimate fine art of jīngjù music and singing. He was an inspiration to all of us who learned from him. And to his spouse, Zhāng Qìnglán 张庆兰, for her motherly love during my jīngjù research in Nánjīng 南京. Sūn Jiàn’ān 孙建安, for being a great mentor to me, bringing me along on all occasions, introducing me to the production team which initiated the project for my dissertation, attending the kūnqǔ performances in which he was involved, meeting his kūnqǔ expert friends, listening to his music lessons, and more; anything which he thought might benefit my understanding of all aspects of kūnqǔ. I am grateful for all his support and his profound knowledge of kūnqǔ music composition. Wichmann-Walczak, Elizabeth, for her years of endeavor producing jīngjù productions in the US. -

From Story to Script: Towards a Morphology of the Peony Pavilion–– a Dream/ Ghost Drama from Ming China

From Story to Script: towards a Morphology of The Peony Pavilion–– a Dream/ Ghost Drama from Ming China Xiaohuan Zhao University of Otago, Donghua University This article is an attempt to analyze the dramatic structure of the Mudan ting 牡丹 亭 (Peony Pavilion) as a piece of fantasy which Tang Xianzu 湯顯祖 (1550–1616) created through the utilisation of structural devices and techniques of magic tales. The particular model adopted for the textual analysis is that formulated by Vladimir Propp in Morphology of Russian Folktale. This paper starts with a comparison of Russian magic tales Propp investigated for his morphological study and Chinese zhiguai 志怪 tales which provide the prototype for the Mudan ting with a view of justifying the application of the Proppian model. The second part of this paper is devoted to a critical review of the Proppian model and method in terms of function versus non-function, tale versus move, and character versus tale / theatrical role. Further information is also given in this part as a response to challenges and criticisms this article may incur as regards the applicability of the Proppian model in inter-cultural and inter-generic studies. Part Three is a morphological analysis of the dramatic text with a focus on the main storyline revolving around the hero and heroine. In the course of textual analysis, the particular form and sequence of functions is identified, the functional scheme of each move presented, and the distribution of dramatis personae in accordance with the sphere(s) of action of characters delineated. Finally this paper concludes with a presentation of the overall dramatic structure and strategy of this play. -

Politics, Classicism, and Medicine During the Eighteenth Century 十八世紀在德川日本 "頌華者" 和 "貶華者" 的 問題 – 以中醫及漢方為主

East Asian Science, Technology and Society: an International Journal DOI 10.1007/s12280-008-9042-9 Sinophiles and Sinophobes in Tokugawa Japan: Politics, Classicism, and Medicine During the Eighteenth Century 十八世紀在德川日本 "頌華者" 和 "貶華者" 的 問題 – 以中醫及漢方為主 Benjamin A. Elman Received: 12 May 2008 /Accepted: 12 May 2008 # National Science Council, Taiwan 2008 Abstract This article first reviews the political, economic, and cultural context within which Japanese during the Tokugawa era (1600–1866) mastered Kanbun 漢 文 as their elite lingua franca. Sino-Japanese cultural exchanges were based on prestigious classical Chinese texts imported from Ming (1368–1644) and Qing (1644–1911) China via the controlled Ningbo-Nagasaki trade and Kanbun texts sent in the other direction, from Japan back to China. The role of Japanese Kanbun teachers in presenting language textbooks for instruction and the larger Japanese adaptation of Chinese studies in the eighteenth century is then contextualized within a new, socio-cultural framework to understand the local, regional, and urban role of the Confucian teacher–scholar in a rapidly changing Tokugawa society. The concluding part of the article is based on new research using rare Kanbun medical materials in the Fujikawa Bunko 富士川文庫 at Kyoto University, which show how some increasingly iconoclastic Japanese scholar–physicians (known as the Goiha 古醫派) appropriated the late Ming and early Qing revival of interest in ancient This article is dedicated to Nathan Sivin for his contributions to the History of Science and Medicine in China. Unfortunately, I was unable to present it at the Johns Hopkins University sessions in July 2008 honoring Professor Sivin or include it in the forthcoming Asia Major festschrift in his honor. -

Representing Talented Women in Eighteenth-Century Chinese Painting: Thirteen Female Disciples Seeking Instruction at the Lake Pavilion

REPRESENTING TALENTED WOMEN IN EIGHTEENTH-CENTURY CHINESE PAINTING: THIRTEEN FEMALE DISCIPLES SEEKING INSTRUCTION AT THE LAKE PAVILION By Copyright 2016 Janet C. Chen Submitted to the graduate degree program in Art History and the Graduate Faculty of the University of Kansas in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy. ________________________________ Chairperson Marsha Haufler ________________________________ Amy McNair ________________________________ Sherry Fowler ________________________________ Jungsil Jenny Lee ________________________________ Keith McMahon Date Defended: May 13, 2016 The Dissertation Committee for Janet C. Chen certifies that this is the approved version of the following dissertation: REPRESENTING TALENTED WOMEN IN EIGHTEENTH-CENTURY CHINESE PAINTING: THIRTEEN FEMALE DISCIPLES SEEKING INSTRUCTION AT THE LAKE PAVILION ________________________________ Chairperson Marsha Haufler Date approved: May 13, 2016 ii Abstract As the first comprehensive art-historical study of the Qing poet Yuan Mei (1716–97) and the female intellectuals in his circle, this dissertation examines the depictions of these women in an eighteenth-century handscroll, Thirteen Female Disciples Seeking Instructions at the Lake Pavilion, related paintings, and the accompanying inscriptions. Created when an increasing number of women turned to the scholarly arts, in particular painting and poetry, these paintings documented the more receptive attitude of literati toward talented women and their support in the social and artistic lives of female intellectuals. These pictures show the women cultivating themselves through literati activities and poetic meditation in nature or gardens, common tropes in portraits of male scholars. The predominantly male patrons, painters, and colophon authors all took part in the formation of the women’s public identities as poets and artists; the first two determined the visual representations, and the third, through writings, confirmed and elaborated on the designated identities. -

National Ballet of China Feng Ying, Artistic Director the Peony Pavilion Ballet in Two Acts and Six Scenes Adapted from Tang Xianzu’S Play of the Same Name

07-08 Peony_Gp 3.qxt 6/29/15 2:42 PM Page 1 Lincoln Center Festival lead support is provided by American Express July 8 – 10 David H. Koch Theater National Ballet of China Feng Ying, Artistic Director The Peony Pavilion Ballet in two acts and six scenes Adapted from Tang Xianzu’s play of the same name Producer Zhao Ruheng Adaptation and Director Li Liuyi Composer, Arranger, and Orchestrator Guo Wenjing Choreographer Fei Bo Set Designer Michael Simon Costume Designer Emi Wada Lighting Designers Michael Simon, Han Jiang National Ballet of China Symphony Orchestra Conductors Zhang Yi, Liu Ju Approximate performance time: 2 hours, including one intermission Major support for Lincoln Center Festival 2015 is provided by The Andrew W. Mellon Foundation. This performance is made possible in part by the Josie Robertson Fund for Lincoln Center. Lincoln Center Festival 2015 is made possible in part with public funds from the New York City Department of Cultural Affairs, New York State Council on the Arts, and the National Endowment for the Arts. Endowment support for the Lincoln Center Festival 2015 presentation of the National Ballet of China is provided by Blavatnik Family Foundation Fund for Dance. The Lincoln Center Festival 2015 presentation of the National Ballet of China is made possible in part by generous support from Yang Lan and The Joelson Foundation. National Ballet of China’s participation in Lincoln Center Festival is made possible by the support of the Ministry of Culture of China and the China National Arts Fund. 07-08 Peony_Gp 3.qxt 6/29/15 2:42 PM Page 2 LINCOLN CENTER FESTIVAL 2015 THE PEONY PAVILION July 8, 2015, at 8:00 p.m. -

How I Enjoyed the Peony Pavilion!

FEATURE How I Enjoyed The Peony Pavilion! By Chia-Hui Shih I enjoyed the performance of The Peony Pavilion so much that I wrote of my experiences with the show in two parts: first my overall impression as a layman and then my appreciation of the performance on each of the three days that the show lasted. Part I: A Layman’s Experience On September 22 to 24, I watched The Peony Pavilion at the Barclay Theater in Irvine, Calif. It was presented by a Chinese Kunqu opera company from Suzhou, Jiangsu Province. Tang Xian Zu (the Ming Dynasty, 1550- 1616) wrote the libretti, originally consisting of 55 acts. I have never seen a Kunqu production, nor even heard any recital of Kunqu. My closer encounter with the play came some twenty years The melodies (if they could be called ago when I read a play written by Bai Xian Yong melodies, more like tones) in Kunqu are quite (the producer of The Peony Pavilion) named different from those in the popular Jingju (Peking “Visiting a Garden, Startled in a Dream”. It was Opera), are more monotonous—at least to the based on one episode of The Peony Pavilion. untrained ears of mine. On the other hand, the non-singing parts, such as the movement of eyes, hands, and arms; walking styles of men and women; and the dialogue were quite similar to those in Jingju. Actually I had expected that the spoken lines would be the dialect of Suzhou, but it turned out to be a mixture of Mandarin and some Jiangsu dialects, including that of Suzhou. -

The Zhou Dynasty Around 1046 BC, King Wu, the Leader of the Zhou

The Zhou Dynasty Around 1046 BC, King Wu, the leader of the Zhou (Chou), a subject people living in the west of the Chinese kingdom, overthrew the last king of the Shang Dynasty. King Wu died shortly after this victory, but his family, the Ji, would rule China for the next few centuries. Their dynasty is known as the Zhou Dynasty. The Mandate of Heaven After overthrowing the Shang Dynasty, the Zhou propagated a new concept known as the Mandate of Heaven. The Mandate of Heaven became the ideological basis of Zhou rule, and an important part of Chinese political philosophy for many centuries. The Mandate of Heaven explained why the Zhou kings had authority to rule China and why they were justified in deposing the Shang dynasty. The Mandate held that there could only be one legitimate ruler of China at one time, and that such a king reigned with the approval of heaven. A king could, however, loose the approval of heaven, which would result in that king being overthrown. Since the Shang kings had become immoral—because of their excessive drinking, luxuriant living, and cruelty— they had lost heaven’s approval of their rule. Thus the Zhou rebellion, according to the idea, took place with the approval of heaven, because heaven had removed supreme power from the Shang and bestowed it upon the Zhou. Western Zhou After his death, King Wu was succeeded by his son Cheng, but power remained in the hands of a regent, the Duke of Zhou. The Duke of Zhou defeated rebellions and established the Zhou Dynasty firmly in power at their capital of Fenghao on the Wei River (near modern-day Xi’an) in western China. -

READING BODIES: AESTHETICS, GENDER, and FAMILY in the EIGHTEENTH-CENTURY CHINESE NOVEL GUWANGYAN (PREPOSTEROUS WORDS) by QING

READING BODIES: AESTHETICS, GENDER, AND FAMILY IN THE EIGHTEENTH-CENTURY CHINESE NOVEL GUWANGYAN (PREPOSTEROUS WORDS) by QING YE A DISSERTATION Presented to the Department of East Asian Languages and Literatures and the Graduate School of the University of Oregon in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy June 2016 DISSERTATION APPROVAL PAGE Student: Qing Ye Title: Reading Bodies: Aesthetics, Gender, and Family in the Eighteenth Century Chinese Novel Guwangyan (Preposterous Words) This dissertation has been accepted and approved in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Doctor of Philosophy in the Department of East Asian Languages and Literatures by: Maram Epstein Chairperson Yugen Wang Core Member Alison Groppe Core Member Ina Asim Institutional Representative and Scott L. Pratt Dean of the Graduate School Original approval signatures are on file with the University of Oregon Graduate School. Degree awarded June 2016 ii © 2016 Qing Ye iii DISSERTATION ABSTRACT Qing Ye Doctor of Philosophy Department of East Asian Languages and Literature June 2016 Title: Reading Bodies: Aesthetic, Gender, and Family in the Eighteenth Century Chinese Novel Guwangyan (Preposterous Words) This dissertation focuses on the Mid-Qing novel Guwangyan (Preposterous Words, preface dated, 1730s) which is a newly discovered novel with lots of graphic sexual descriptions. Guwangyan was composed between the publication of Jin Ping Mei (The Plum in the Golden Vase, 1617) and Honglou meng (Dream of the Red Chamber, 1791). These two masterpieces represent sexuality and desire by presenting domestic life in polygamous households within a larger social landscape. This dissertation explores the factors that shifted the literary discourse from the pornographic description of sexuality in Jin Ping Mei, to the representation of chaste love in Honglou meng. -

On Wang Rongpei's Drama Translation Strategy

ISSN 1923-1555[Print] Studies in Literature and Language ISSN 1923-1563[Online] Vol. 17, No. 3, 2018, pp. 28-34 www.cscanada.net DOI:10.3968/10688 www.cscanada.org On Wang Rongpei’s Drama Translation Strategy: A Case Study of The Peony Pavilion CAO Shuo[a]; GAO Jingyang[b],*; JIANG Ying[b],* [a] Associate Professor. School of Foreign Languages, Dalian University Key words: The Peony Pavilion; Wang Rongpei; of Technology, Dalian, China. Translation strategy [b]School of Foreign Languages, Dalian University of Technology, Dalian, China. *Corresponding author. Cao, S., Gao, J. Y., & Jiang, Y. (2018). On Wang Rongpei’s Drama Translation Strategy: A Case Study of The Peony Pavilion. Supported by Planning Fund of Social Sciences in Liaoning Province Studies in Literature and Language, 17(3), 28-34. Available (LI3DYY035). from: http://www.cscanada.net/index.php/sll/article/view/10688 DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.3968/10688 Received 22 September 2018; accepted 28 November 2018 Published online 26 December 2018 Abstract INTRODUCTION As a special literary form, drama is characterized by Kunqu Opera has a very high value of history, literature personalization, colloquialization, rhythm and the feature and art, embodying a rich aesthetic connotations and of performability. For a long time, the focus of drama profound cultural implications. During the development translation studies has also fallen on the “performability” of Kunqu Opera, the literati and artists crafted Kunqu at home and abroad. The Peony Pavilion is one of the Opera meticulously and learnt widely from other masterpieces in ancient China. With its beautiful and opera in instruments, vocal music, performances and elegant lyrics, engaging anecdotes and vivid characters, choreography, making it extremely popular in the The Peony Pavilion has an enduring popularity on the society. -

The Peony Pavilion

Advances in Social Science, Education and Humanities Research, volume 232 4th International Conference on Arts, Design and Contemporary Education (ICADCE 2018) Tension and Flow: an Analysis on the Emotional Structure of The Peony Pavilion Yanping Chen Collage of Literature and Journalism Sichuan University Chengdu, China 610064 Abstract—Influenced by the conditions of developed and even resonance. Through this subtle influence, readers commodities economy and Yang Ming philosophy of mind, receive irreplaceable emotional education. This is an there emerged a new wave of social thoughts focusing on emerging emotional concept that is different from traditional secularism and affirming human desire in the middle and late feudal ethics and is based on the affirmation of lust. It was Ming Dynasty. Tang Xianzu, who has fully absorbed the rejected and guarded by the feudal Guardian. In the 42nd essence of this emerging social thought trend, has involved it chapter of “A Dream of Red Mansions”, the secret warning into the legendary The Peony Pavilion in a creative way. This of Xue Baochai's warning to Lin Daiyu was the evidence, work, which affirms the desires of the secular people, has and she used the admonitory words: "I'm most afraid of stroked the dominant social concept with the core of Cheng being changed by miscellaneous book". It also proves that Zhu’s Neo-Confucianism in a very clear-cut manner. In the the book "The Peony Pavilion" shaped the temperament of works, this sharp contradiction is deeply expanded. The emotional tensions reflected in the development and evolution the girls in the Ming and Qing Dynasties. -

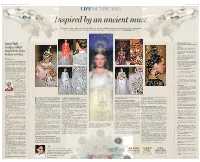

DUNHUANG Inspired by an Ancient Muse

18 CHINA DAILY | HONG KONG EDITION Tuesday, November 12, 2019 | 19 LIFE DUNHUANG Inspired by an ancient muse The Mogao Caves — part of the ancient Silk Road — provide endless inspiration for designer Xiong Ying, helping her to take her fashion house, Heaven Gaia, to new levels on the international stage, Chen Nan reports. Great Hall History set in stone Digging in designs reflect • In 366, the first cave is carved by Yuezun, a Bud dhist monk who happens to visit Dunhuang. inspiration from • The first largescale boring of grottoes begins in Dunhuang during the Northern Liang (401439) Gansu caverns kingdom period. • Rulers of the Northern Wei (386534), Western Wei (535556) and Northern Zhou (557581) By LIN QI dynasties follow Buddhism and contribute to the [email protected] expansion of the grottoes. When construction of the Great Hall of the Peo • Booming trade along the ancient Silk Road gradu ple began in 1958, thenpremier Zhou Enlai sug ally helps the Mogao Caves become prominent in the gested while overseeing the project that talented seventh and the eighth centuries. During the reign of young Chinese have the opportunity to partici empress Wu Zetian of the Tang Dynasty (618907), pate. more than 1,000 caves exist at the site. Chang Shana, then 27, was among the artists chosen. A teacher at the Central Academy of Arts • Dunhuang is ruled by the Tibetan Tubo regime and Design (now Tsinghua University’s Academy from 781 to 848, who dig 56 caves. of Arts and Design) at the time, Chang got the chance after being noticed in China’s art world for • Local warlords govern Dunhuang from 848 to her accurate copies of the mural paintings inside 1036, creating many family grottoes. -

Peony Review

RESURRECTION: A PEONY BLOOMS IN NEW YORK (PUBLISHED AUGUST 1999, THREE-PART SERIES, CHINANOW.COM) “HOW LITTLE IT IS KNOWN THAT THAT WHICH CANNOT BE IN THE REALM OF REASON [理] SIMPLY HAS TO BE IN THE REALM OF LOVE [情]!” --Tang Xianzu, Author’s Preface to The Peony Pavilion [牡丹亭] (1598) EVERY ASPECT OF THE PEONY PAVILION THAT OPENED ON JULY 7 TO A SOLD-OUT 965- seat house radiated the labors of love invested in this politically and culturally fraught production. Despite an international debacle that sidelined the original 1998 production and the rancorous debates over conflicts between Western and Chinese performance methods, the passion director Chen Shizheng [陈士争] instilled in his Peony cannot be doubted, even when ardor blinded better judgement. The seminal opera of the late-Ming (1368-1644) culture of love [情], Peony Pavilion is widely regarded as Tang Xianzu’s greatest work and exemplifies Chinese Kunqu Opera at the height of its sophistication and complexity. One hour longer than Wagner’s Ring Cycle, Peony uses 160 characters to spin a 22-hour tale. Set against the political and military machinations of Southern bandits and the vagaries of feudal appointments, a love story both timeless and stateless unfolds between Du Liniang (played by Qian Yi [钱 熠]]) and Liu Mengmei (Wen Yuhang [温 宇 航]). Driven by visions of each other in their dreams, Liu renames himself in honor of the beauty beckoning him from underneath the plum tree. Holding no hope that she will be able to consummate her dream-love due to traditional conventions of betrothal, Du slowly pines to her death.