Python Library Reference Release 2.1.1

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

SETL for Internet Data Processing

SETL for Internet Data Processing by David Bacon A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Computer Science New York University January, 2000 Jacob T. Schwartz (Dissertation Advisor) c David Bacon, 1999 Permission to reproduce this work in whole or in part for non-commercial purposes is hereby granted, provided that this notice and the reference http://www.cs.nyu.edu/bacon/phd-thesis/ remain prominently attached to the copied text. Excerpts less than one PostScript page long may be quoted without the requirement to include this notice, but must attach a bibliographic citation that mentions the author’s name, the title and year of this disser- tation, and New York University. For my children ii Acknowledgments First of all, I would like to thank my advisor, Jack Schwartz, for his support and encour- agement. I am also grateful to Ed Schonberg and Robert Dewar for many interesting and helpful discussions, particularly during my early days at NYU. Terry Boult (of Lehigh University) and Richard Wallace have contributed materially to my later work on SETL through grants from the NSF and from ARPA. Finally, I am indebted to my parents, who gave me the strength and will to bring this labor of love to what I hope will be a propitious beginning. iii Preface Colin Broughton, a colleague in Edmonton, Canada, first made me aware of SETL in 1980, when he saw the heavy use I was making of associative tables in SPITBOL for data processing in a protein X-ray crystallography laboratory. -

R L W D by Oktie Hassanzadeh A

R L W D by Oktie Hassanzadeh A thesis submitted in conformity with the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Graduate Department of Computer Science University of Toronto Copyright © 2012 by Oktie Hassanzadeh Abstract Record Linkage for Web Data Oktie Hassanzadeh Doctor of Philosophy Graduate Department of Computer Science University of Toronto 2012 Record linkage refers to the task of nding and linking records (in a single database or in a set of data sources) that refer to the same entity. Automating the record linkage process is a challenging problem, and has been the topic of extensive research for many years. Several tools and techniques have been developed as part of research prototypes and commercial so- ware systems. However, the changing nature of the linkage process and the growing size of data sources create new challenges for this task. In this thesis, we study the record linkage problem for Web data sources. We show that tra- ditional approaches to record linkage fail to meet the needs of Web data because 1) they do not permit users to easily tailor string matching algorithms to be useful over the highly heteroge- neous and error-riddled string data on the Web and 2) they assume that the attributes required for record linkage are given. We propose novel solutions to address these shortcomings. First, we present a framework for record linkage over relational data, motivated by the fact that many Web data sources are powered by relational database engines. is framework is based on declarative specication of the linkage requirements by the user and allows linking records in many real-world scenarios. -

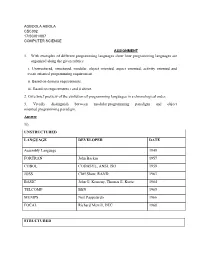

1. with Examples of Different Programming Languages Show How Programming Languages Are Organized Along the Given Rubrics: I

AGBOOLA ABIOLA CSC302 17/SCI01/007 COMPUTER SCIENCE ASSIGNMENT 1. With examples of different programming languages show how programming languages are organized along the given rubrics: i. Unstructured, structured, modular, object oriented, aspect oriented, activity oriented and event oriented programming requirement. ii. Based on domain requirements. iii. Based on requirements i and ii above. 2. Give brief preview of the evolution of programming languages in a chronological order. 3. Vividly distinguish between modular programming paradigm and object oriented programming paradigm. Answer 1i). UNSTRUCTURED LANGUAGE DEVELOPER DATE Assembly Language 1949 FORTRAN John Backus 1957 COBOL CODASYL, ANSI, ISO 1959 JOSS Cliff Shaw, RAND 1963 BASIC John G. Kemeny, Thomas E. Kurtz 1964 TELCOMP BBN 1965 MUMPS Neil Pappalardo 1966 FOCAL Richard Merrill, DEC 1968 STRUCTURED LANGUAGE DEVELOPER DATE ALGOL 58 Friedrich L. Bauer, and co. 1958 ALGOL 60 Backus, Bauer and co. 1960 ABC CWI 1980 Ada United States Department of Defence 1980 Accent R NIS 1980 Action! Optimized Systems Software 1983 Alef Phil Winterbottom 1992 DASL Sun Micro-systems Laboratories 1999-2003 MODULAR LANGUAGE DEVELOPER DATE ALGOL W Niklaus Wirth, Tony Hoare 1966 APL Larry Breed, Dick Lathwell and co. 1966 ALGOL 68 A. Van Wijngaarden and co. 1968 AMOS BASIC FranÇois Lionet anConstantin Stiropoulos 1990 Alice ML Saarland University 2000 Agda Ulf Norell;Catarina coquand(1.0) 2007 Arc Paul Graham, Robert Morris and co. 2008 Bosque Mark Marron 2019 OBJECT-ORIENTED LANGUAGE DEVELOPER DATE C* Thinking Machine 1987 Actor Charles Duff 1988 Aldor Thomas J. Watson Research Center 1990 Amiga E Wouter van Oortmerssen 1993 Action Script Macromedia 1998 BeanShell JCP 1999 AngelScript Andreas Jönsson 2003 Boo Rodrigo B. -

Python in Education Teach, Learn, Program

ANALYZING THE ANALYZERS THE ANALYZING Python in Education Teach, Learn, Program Nicholas H. Tollervey ISBN: 978-1-491-92462-4 Python in Education Teach, Learn, Program Nicholas H.Tollervey Python in Education by Nicholas H. Tollervey Copyright © 2015 O’Reilly Media, Inc. All rights reserved. Printed in the United States of America. Published by O’Reilly Media, Inc., 1005 Gravenstein Highway North, Sebastopol, CA 95472. O’Reilly books may be purchased for educational, business, or sales promotional use. Online editions are also available for most titles (http://safaribooksonline.com). For more information, contact our corporate/institutional sales department: 800-998-9938 or [email protected]. Editor: Meghan Blanchette Interior Designer: David Futato Production Editor: Kristen Brown Cover Designer: Karen Montgomery Copyeditor: Gillian McGarvey Illustrator: Rebecca Demarest April 2015: First Edition Revision History for the First Edition 2015-03-11: First Release See http://oreilly.com/catalog/errata.csp?isbn=9781491924624 for release details. The O’Reilly logo is a registered trademark of O’Reilly Media, Inc. Python in Educa‐ tion, the cover image, and related trade dress are trademarks of O’Reilly Media, Inc. While the publisher and the author have used good faith efforts to ensure that the information and instructions contained in this work are accurate, the publisher and the author disclaim all responsibility for errors or omissions, including without limi‐ tation responsibility for damages resulting from the use of or reliance on this work. Use of the information and instructions contained in this work is at your own risk. If any code samples or other technology this work contains or describes is subject to open source licenses or the intellectual property rights of others, it is your responsi‐ bility to ensure that your use thereof complies with such licenses and/or rights. -

Using String Metrics to Improve the Design of Virtual Conversational Characters: Behavior Simulator Development Study

JMIR SERIOUS GAMES García-Carbajal et al Original Paper Using String Metrics to Improve the Design of Virtual Conversational Characters: Behavior Simulator Development Study Santiago García-Carbajal1*, PhD; María Pipa-Muniz2*, MSc; Jose Luis Múgica3*, MSc 1Computer Science Department, Universidad de Oviedo, Gijón, Spain 2Cabueñes Hospital, Gijón, Spain 3Signal Software SL, Parque Científico Tecnológico de Gijón, Gijón, Asturias, Spain *all authors contributed equally Corresponding Author: Santiago García-Carbajal, PhD Computer Science Department Universidad de Oviedo Campus de Viesques Office 1 b 15 Gijón, 33203 Spain Phone: 34 985182487 Email: [email protected] Abstract Background: An emergency waiting room is a place where conflicts often arise. Nervous relatives in a hostile, unknown environment force security and medical staff to be ready to deal with some awkward situations. Additionally, it has been said that the medical interview is the first diagnostic and therapeutic tool, involving both intellectual and emotional skills on the part of the doctor. At the same time, it seems that there is something mysterious about interviewing that cannot be formalized or taught. In this context, virtual conversational characters (VCCs) are progressively present in most e-learning environments. Objective: In this study, we propose and develop a modular architecture for a VCC-based behavior simulator to be used as a tool for conflict avoidance training. Our behavior simulators are now being used in hospital environments, where training exercises must be easily designed and tested. Methods: We define training exercises as labeled, directed graphs that help an instructor in the design of complex training situations. In order to increase the perception of talking to a real person, the simulator must deal with a huge number of sentences that a VCC must understand and react to. -

Study of Twitter Sentiment Analysis Using Machine Learning Algorithms on Python

International Journal of Computer Applications (0975 – 8887) Volume 165 – No.9, May 2017 Study of Twitter Sentiment Analysis using Machine Learning Algorithms on Python Bhumika Gupta, PhD Monika Negi, Kanika Vishwakarma, Goldi Assistant Professor, C.S.E.D Rawat, Priyanka Badhani G.B.P.E.C, Pauri, Uttarakhand, India B.Tech, C.S.E.D G.B.P.E.C Uttarakhand, India ABSTRACT 2. ABOUT SENTIMENT ANALYSIS Twitter is a platform widely used by people to express their Sentiment analysis is a process of deriving sentiment of a opinions and display sentiments on different occasions. particular statement or sentence. It’s a classification technique Sentiment analysis is an approach to analyze data and retrieve which derives opinion from the tweets and formulates a sentiment that it embodies. Twitter sentiment analysis is an sentiment and on the basis of which, sentiment classification application of sentiment analysis on data from Twitter is performed. (tweets), in order to extract sentiments conveyed by the user. In the past decades, the research in this field has consistently Sentiments are subjective to the topic of interest. We are grown. The reason behind this is the challenging format of the required to formulate that what kind of features will decide for tweets which makes the processing difficult. The tweet format the sentiment it embodies. is very small which generates a whole new dimension of In the programming model, sentiment we refer to, is class of problems like use of slang, abbreviations etc. In this paper, we entities that the person performing sentiment analysis wants to aim to review some papers regarding research in sentiment find in the tweets. -

Redacted VV MQP Report with Math

______________________________________________________________________________ Developing Models to Visualize & Analyze User Interaction for Financial Technology Websites ______________________________________________________________________________ Project Team Amanda Ezeobiejesi Computer Science Guy Katz Industrial Engineering Alissa Ostapenko Computer Science and Mathematical Sciences Project Advisor Professor Michael Ginzberg Foisie Business School Project Co-Advisors Professor Rodica Neamtu Department of Computer Science Professor Sara Saberi Foisie Business School Professor Jon Abraham Department of Mathematical Sciences This report represents the work of WPI undergraduate students submitted to the faculty as evidence of completion of a degree requirement. WPI routinely publishes these reports on its website without editorial or peer review. For more information about the projects program at WPI, please see: http://www.wpi.edu/academics/ugradstudies/project-learning.html Abstract Vestigo Ventures manually processes website traffic data to analyze the business performance of financial technology companies. By analyzing how people navigate through company websites, Vestigo aims to understand different customer activity patterns. Our team designed and implemented a tool that automatically processes clickstream data to visualize different customer activity within a website and compute statistics about user activity. This tool will provide Vestigo insight on the effectiveness of their clients’ website structures and help them make recommendations to their clients. 1 Acknowledgements Our team would like to extend our sincere gratitude to the individuals mentioned below, from Vestigo Ventures, Cogo Labs, and Link Ventures, as well as our advisors for their support and encouragement throughout the duration of this project: Vestigo Ventures Ian Sheridan, a managing director and co-founder of Vestigo Ventures, who made this project possible. He established the initial connection with WPI and checked in on us from time to time. -

An Introduction to Python (PDF)

Introduction to Python Heavily based on presentations by Matt Huenerfauth (Penn State) Guido van Rossum (Google) Richard P. Muller (Caltech) ... Monday, October 19, 2009 Python • Open source general-purpose language. • Object Oriented, Procedural, Functional • Easy to interface with C/ObjC/Java/Fortran • Easy-ish to interface with C++ (via SWIG) • Great interactive environment • Downloads: http://www.python.org • Documentation: http://www.python.org/doc/ • Free book: http://www.diveintopython.org Monday, October 19, 2009 2.5.x / 2.6.x / 3.x ??? • “Current” version is 2.6.x • “Mainstream” version is 2.5.x • The new kid on the block is 3.x You probably want 2.5.x unless you are starting from scratch. Then maybe 3.x Monday, October 19, 2009 Technical Issues Installing & Running Python Monday, October 19, 2009 Binaries • Python comes pre-installed with Mac OS X and Linux. • Windows binaries from http://python.org/ • You might not have to do anything! Monday, October 19, 2009 The Python Interpreter • Interactive interface to Python % python Python 2.5 (r25:51908, May 25 2007, 16:14:04) [GCC 4.1.2 20061115 (prerelease) (SUSE Linux)] on linux2 Type "help", "copyright", "credits" or "license" for more information. >>> • Python interpreter evaluates inputs: >>> 3*(7+2) 27 • Python prompts with ‘>>>’. • To exit Python: • CTRL-D Monday, October 19, 2009 Running Programs on UNIX % python filename.py You could make the *.py file executable and add the following #!/usr/bin/env python to the top to make it runnable. Monday, October 19, 2009 Batteries Included • Large collection of proven modules included in the standard distribution. -

An Introduction to Python Release 2.2.2

An Introduction to Python Release 2.2.2 Guido van Rossum Fred L. Drake, Jr., editor PythonLabs Email: [email protected] A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library. First printing, April 2003 (14/4/2003). Published by Network Theory Limited. 15 Royal Park Clifton Bristol BS8 3AL United Kingdom Email: [email protected] ISBN 0-9541617-6-9 Further information about this book is available from http://www.network-theory.co.uk/python/manual/ Additional section authors: Using Lists as Stacks by Ka-Ping Yee Floating Point Arithmetic — Issues and Limitations by Tim Peters Unicode Strings by Marc-Andre Lemburg Summary of changes made for this edition by Network Theory Ltd: Minor editing of text and examples for formatting as a book. Added Publisher’s preface. Moved Abstract to Introduction. Additional entries and modifications to index. Some paragraphs, sentences and footnotes removed/edited for con- ciseness. A complete set of differences can be found at http://www.network- theory.co.uk/python/manual/src/ Copyright c 2001Python Software Foundation. All rights reserved. Copyright c 2000 BeOpen.com. All rights reserved. Copyright c 1995-2000 Corporation for National Research Initiatives. All rights reserved. Copyright c 1991-1995 Stichting Mathematisch Centrum. All rights re- served. See the end of this document for complete license and permissions infor- mation. Contents Publisher’s Preface 1 Introduction 3 1 Whetting Your Appetite 5 1.1 WhereFromHere...................... 6 2 Using the Python Interpreter 7 2.1InvokingtheInterpreter................... 7 2.2 TheInterpreterandItsEnvironment........... 9 3 An Informal Introduction to Python 11 3.1Using Python as a Calculator ............... -

Python Is Eating the World: How One Developer’S Side Project Became the Hottest Programming Language on the Planet

Python is eating the world: How one developer’s side project became the hottest programming language on the planet By Nick Heath Image: Dan Stroud under the Creative Commons licence Guido van Rossum at Dropbox headquarters in 2014. Frustrated by programming language shortcomings, Guido van Rossum created Python. With the language now used by millions, Nick Heath talks to van Rossum about Python’s past and explores what’s next. In late 1994, a select group of programmers from across the US met to discuss their new secret weapon. Barry Warsaw was one of the 20 or so developers present at that first-ever workshop for the newly- created Python programming language and recalls the palpable excitement among those early users. “I can remember one person in particular who said, ‘You cannot tell anybody that I’m here because our use of Python is a competitive advantage.’ It was their secret weapon, right?” Even at that early meeting, at the then US National Standards Bureau in Maryland, Warsaw says it was evident that Python offered something new in how easy it was to write code and simply get things done. “When I first was introduced to Python, I knew there was something special. It was some combination of readability, and there was a joy to writing Python code,” he remembers. Today enthusiasm for Python has spread far beyond that initial circle of developers, and some are predicting it will soon become the most popular programming language in the world, as it continues to add new users faster than any other language. -

(Pdf) of the School of Squiggol: a History of the Bird−Meertens

The School of Squiggol A History of the Bird{Meertens Formalism Jeremy Gibbons University of Oxford Abstract. The Bird{Meertens Formalism, colloquially known as \Squig- gol", is a calculus for program transformation by equational reasoning in a function style, developed by Richard Bird and Lambert Meertens and other members of IFIP Working Group 2.1 for about two decades from the mid 1970s. One particular characteristic of the development of the Formalism is fluctuating emphasis on novel `squiggly' notation: sometimes favouring notational exploration in the quest for conciseness and precision, and sometimes reverting to simpler and more rigid nota- tional conventions in the interests of accessibility. This paper explores that historical ebb and flow. 1 Introduction In 1962, IFIP formed Working Group 2.1 to design a successor to the seminal algorithmic language Algol 60 [4]. WG2.1 eventually produced the specification for Algol 68 [63, 64]|a sophisticated language, presented using an elaborate two- level description notation, which received a mixed reception. WG2.1 continues to this day; technically, it retains responsibility for the Algol languages, but practi- cally it takes on a broader remit under the current name Algorithmic Languages and Calculi. Over the years, the Group has been through periods of focus and periods of diversity. But after the Algol 68 project, the period of sharpest focus covered the two decades from the mid 1970s to the early 1990s, when what later became known as the Bird{Meertens Formalism (BMF) drew the whole group together again. It is the story of those years that is the subject of this paper. -

Introduction to Computational & Quantitative Biology (G4120)

ICQB Introduction to Computational & Quantitative Biology (G4120) Fall 2019 Oliver Jovanovic, Ph.D. Columbia University Department of Microbiology & Immunology Lecture 5: Introduction to Programming October 15, 2019 History of Programming 1831 Lady Ada Lovelace writes the first computer program for Charles Babbage’s Analytical Engine. 1936 Alan Turing develops the theoretical concept of the Turing Machine, forming the basis of modern computer programming. 1943 Plankalkül, the first formal computer language, is developed by Konrad Zuse, a German engineer, which he later applies to, among other things, chess. 1945 John von Neumann develops the theoretical concepts of shared program technique and conditional control transfer. 1949 Short Code, the first computer language actually used on an electronic computer, appears. 1951 A-O, the first widely used complier, is designed by Grace Hopper at Remington Rand. 1954 FORTRAN (FORmula TRANslating system) language is developed by John Backus at IBM for scientific computing. 1958 ALGOL, the first programming language with a formal grammar, is developed by John Backus for scientific applications 1958 LISP (LISt Processing) language is created by John McCarthy of MIT for Artificial Intelligence (AI) research. 1959 COBOL is created by the Conference on Data Systems and Languages (CODASYL) for business programming, and becomes widely used with the support of Admiral Grace Hopper. 1964 BASIC (Beginner’s All-purpose Symbolic Instruction Code) is created by John Kemeny and Thomas Kurtz as an introductory programming