Translation Approaches in Rendering Names of Tourist Sites

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A List of Achievement Tion of the Grand Canal As an Example

18 | Thursday, July 29, 2021 HONG KONG EDITION | CHINA DAILY LIFE | WORLD HERITAGE uanzhou has been added system and pursuit of the harmony to the UNESCO World between people and their environ- Heritage List, marking Inclusion of Quanzhou as a UNESCO World Heritage Site shows China’s ment, Lyu Zhou, director of Tsing- the end of a long-awaited hua University National Heritage Q process. Preparation of long, concerted efforts in cultural conservation, Wang Kaihao reports. Center, said at a side event on con- the city’s bid for World Heritage sta- servation and sustainable develop- tus was launched in 2001. ment of historic urban landscapes Talking about the selection pro- held at the ongoing 44th Session of cess of World Heritage candidates in the World Heritage Committee in China, President Xi Jinping said in Fuzhou, capital of Fujian province. 2016 that the work should highlight “The effort of seeking World Heri- the historical and cultural values of tage status is just a channel to Chinese civilization, reflect Chinese enhance the protection of old cities, people’s spiritual pursuit, and show which is a challenge commonly a complete and real image of China faced across the world in urban in both ancient and modern times to development,” Lyu said. the rest of the world. “Many of our experiences, includ- With the inscription of “Quan- ing comprehensive conservation of zhou: Emporium of the World in cultural heritage sites, the timely Song-Yuan China”, China now has 56 drafting of plans and people-centric UNESCO World Heritage sites, of ideas (in site protection), can be ref- which 38 are cultural, 14 natural and erential for the international com- four a mix of cultural and natural munity.” sites — higher than most other coun- In China, there are about 70 local tries in each category. -

Confucius & Shaolin Monastery

Guaranteed Departures • Tour Guide from Canada • Senior (60+) Discount C$50 • Early Bird Discount C$100 Highly Recommend (Confucius & Shaolin Monastery) (Tour No.CSSG) for China Cultural Tour Second Qingdao, Qufu, Confucius Temple, Mt. Taishan, Luoyang, Longmen Grottoes, Zhengzhou, Visit China Kaifeng, Shaolin Monastery 12 Days (10-Night) Deluxe Tour ( High Speed Train Experience ) Please be forewarned that the hour-long journey includes strenuous stair climbing. The energetic may choose to skip the cable car and conquer the entire 6000 steps on foot. Head back to your hotel for a Buffet Dinner. ( B / L / SD ) Hotel: Blossom Hotel Tai’an (5-star) Day 7 – Tai’an ~ Ji’nan ~ Luoyang (High Speed Train) After breakfast, we drive to Ji’nan, the “City of Springs” get ready to enjoy a tour of the “Best Spring of the World” Baotu Spring and Daming Lake. Then, after lunch, you will take a High-Speed Train to Luoyang, a city in He’nan province. You will be met by your local guide and transferred to your hotel. ( B / L / D ) Hotel: Luoyang Lee Royal Hotel Mudu (5-star) Day 8 – Luoyang ~ Shaolin Monastery ~ Zhengzhou Take a morning visit to Longmen Grottoes a UNESCO World Heritage site regarded as one of the three most famous treasure houses of stone inscriptions in China. Take a ride to Dengfeng (1.5 hour drive). Visit the famous Shaolin Monastery. The Pagoda Forest in Shaolin Temple was a concentration of tomb pagodas for eminent monks, abbots and ranking monks at the temple. You will enjoy world famous Chinese Shaolin Kung-fu Show afterwards. -

Umithesis Lye Feedingghosts.Pdf

UMI Number: 3351397 INFORMATION TO USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. Broken or indistinct print, colored or poor quality illustrations and photographs, print bleed-through, substandard margins, and improper alignment can adversely affect reproduction. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if unauthorized copyright material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. ______________________________________________________________ UMI Microform 3351397 Copyright 2009 by ProQuest LLC All rights reserved. This microform edition is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States Code. _______________________________________________________________ ProQuest LLC 789 East Eisenhower Parkway P.O. Box 1346 Ann Arbor, MI 48106-1346 TABLE OF CONTENTS ABSTRACT iv ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS vi INTRODUCTION The Yuqie yankou – Present and Past, Imagined and Performed 1 The Performed Yuqie yankou Rite 4 The Historical and Contemporary Contexts of the Yuqie yankou 7 The Yuqie yankou at Puti Cloister, Malaysia 11 Controlling the Present, Negotiating the Future 16 Textual and Ethnographical Research 19 Layout of Dissertation and Chapter Synopses 26 CHAPTER ONE Theory and Practice, Impressions and Realities 37 Literature Review: Contemporary Scholarly Treatments of the Yuqie yankou Rite 39 Western Impressions, Asian Realities 61 CHAPTER TWO Material Yuqie yankou – Its Cast, Vocals, Instrumentation -

Conservation of Ancient Sites on the Silk Road

PROCEEDINGS International Mogao Grottes Conference at Dunhuang on the Conservation of Conservation October of Grotto Sites 1993Mogao Grottes Ancient Sites at Dunhuang on the Silk Road October 1993 The Getty Conservation Institute Conservation of Ancient Sites on the Silk Road Proceedings of an International Conference on the Conservation of Grotto Sites Conference organized by the Getty Conservation Institute, the Dunhuang Academy, and the Chinese National Institute of Cultural Property Mogao Grottoes, Dunhuang The People’s Republic of China 3–8 October 1993 Edited by Neville Agnew THE GETTY CONSERVATION INSTITUTE LOS ANGELES Cover: Four bodhisattvas (late style), Cave 328, Mogao grottoes at Dunhuang. Courtesy of the Dunhuang Academy. Photograph by Lois Conner. Dinah Berland, Managing Editor Po-Ming Lin, Kwo-Ling Chyi, and Charles Ridley, Translators of Chinese Texts Anita Keys, Production Coordinator Jeffrey Cohen, Series Designer Hespenheide Design, Book Designer Arizona Lithographers, Printer Printed in the United States of America 10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1 © 1997 The J. Paul Getty Trust All rights reserved The Getty Conservation Institute, an operating program of the J. Paul Getty Trust, works internation- ally to further the appreciation and preservation of the world’s cultural heritage for the enrichment and use of present and future generations. The listing of product names and suppliers in this book is provided for information purposes only and is not intended as an endorsement by the Getty Conservation Institute. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Conservation of ancient sites on the Silk Road : proceedings of an international conference on the conservation of grotto sites / edited by Neville Agnew p. -

4 Days Jiuzhaigou (Double Entry) and Huanglong Private Tour (By Air)

[email protected] +86-28-85593923 4 days Jiuzhaigou (double entry) and Huanglong private tour (by air) https://windhorsetour.com/jiuzhaigou-tour/jiuzhaigou-huanglong-indepth-tour Jiuzhaigou Fly to Jiuzhaigou for an in depth exploration of beautiful Sichuan and local Tibetans life. Two full days offers you a more relaxing opportunity to soak in the atmosphere. Matched with Huanglong National Park enjoy the countless lakes. Type Private Duration 4 days Theme Photography Trip code WS-402 Price From US$ 456 per person Itinerary Jiuzhaigou Vally and Huanglong National park are two hottest popular travel destinations in Sichuan. Jiuzhaigou Vally features breathtaking scenery by its fabled blue and green lakes, spectacular waterfalls, narrow conic karst land forms and its unique wildlife. Huanglong is famous for its colorful lakes, snow-capped peaks, glaciers, mountain landscape, diverse forest ecosystems, waterfall and hot springs. Day 01 : Arrival at Jiuzhaigou / Huanglong National Park Upon arrival at Jiu-Huang airport, pick you up and drive to Huanglong Park (2 hours driving) for sightseeing around 3 - 4 hours, Huanglong National Park is famous for its colorful lakes. Considering your physical condition, you can either enjoy the tour by foot or cable car. Afterward, drive to Jiuzhaigou for overnight. B = Breakfast Day 2-3 : Jiuzhaigou National Park Sightseeing- 2 full days (B) You'll have two full days to visit Jiuzhaigou National Park. With crystal clear lakes, waterfalls, virgin forest, and Tibetan villages to explore, two days will give you enough time to relax and soak in the atmosphere of Jiuzhaigou. You can take the pollution-free sightseeing buses to the top of the valley, then walk down to appreciate the nice scenery along the way. -

Place Names on Taiwan's Tombstones: Facts, Figures, Theories

Place Names on Taiwan's Tombstones Place Names on Taiwan's Tombstones: Facts, Figures, Theories Oliver Streiter, Mei-fang Lin, Ke-rui Yen, Ellen Hsu, Ya-wei Wang National University of Kaohsiung Yoann Goudin, Ecole des Hautes Etudes en Sciences Sociales, Paris Abstract This paper presents a corpus-based study on 8.500 place names inscribed on Taiwan's tombstones. Research on place names on Taiwan's tombstones is promising new perspectives in the research on migration, identity, local customs, or Han culture in general. But how much 'identity' or 'migration' are actually coded in the location names? How can such dimensions reliably be identified? Using the place names, their geographic references, their linguistic features, together with other inscriptions, symbols or images on the tomb, we show how place names can be successfully analyzed. Dimensions encoded in the places names are the religious orientation, ethnic identity, social identity, local identity and historical migrations. New, never published data on Taiwanese tombstones are revealed during our analysis, for some of which the explanation pose new challenges. Keywords: Corpus-based study, Taiwan’s tombstone, migration, identity, local custom, Han culture 1. Introduction 1.1 From Cultural Features to Corpus Tombs and tombstones are important artifacts of a culture which allow analyzing and understanding concepts that are fundamental in a culture. Tombs and tombstones are part of a larger complex of death rituals, which as a rite of transition, is expected to illuminate our understanding of a culture. 34 Oliver Streiter A systematic investigation of the cultural concepts related to death rituals, in time and space, is possible through an electronic corpus that combines qualitative data with objective criteria for comparison and generation. -

Dengfeng Observatory, China

90 ICOMOS–IAU Thematic Study on Astronomical Heritage Archaeological/historical/heritage research: The Taosi site was first discovered in the 1950s. During the late 1970s and early 1980s, archaeologists excavated nine chiefly tombs with rich grave goods, together with large numbers of common burials and dwelling foundations. Archaeologists first discovered the walled towns of the Early and Middle Periods in 1999. The remains of the observatory were first discovered in 2003 and totally uncovered in 2004. Archaeoastronomical surveys were undertaken in 2005. This work has been published in a variety of Chinese journals. Chinese archaeoastronomers and archaeologists are currently conducting further collaborative research at Taosi Observatory, sponsored jointly by the Committee of Natural Science of China and the Academy of Science of China. The project, which is due to finish in 2011, has purchased the right to occupy the main field of the observatory site for two years. Main threats or potential threats to the sites: The most critical potential threat to the observatory site itself is from the burials of native villagers, which are placed randomly. The skyline formed by Taer Hill, which is a crucial part of the visual landscape since it contains the sunrise points, is potentially threatened by mining, which could cause the collapse of parts of the top of the hill. The government of Xiangfen County is currently trying to shut down some of the mines, but it is unclear whether a ban on mining could be policed effectively in the longer term. Management, interpretation and outreach: The county government is trying to purchase the land from the local farmers in order to carry out a conservation project as soon as possible. -

Research on the Space Transformation of Yungang Grottoes Art Heritage and the Design of Wisdom Museum from the Perspective of Digital Humanity

E3S Web of Conferences 23 6 , 05023 (2021) https://doi.org/10.1051/e3sconf/202123605023 ICERSD 2020 Research on the Space transformation of Yungang Grottoes Art Heritage and the Design of wisdom Museum from the perspective of digital Humanity LiuXiaoDan1, 2, XiaHuiWen3 1Jinzhong college, Academy of fine arts, Jinzhong ShanXi, 030619 2Nanjing University, School of History, Nanjing JiangSu, 210023 3Taiyuan University of Technology Academy of arts, Jinzhong ShanXi 030606 *Corresponding author: LiuXiaoDan, No. 199 Wenhua Street, Yuci District, Jinzhong City, Shanxi Province, 030619, China. ABSTRACT: The pace transformation and innovative design of Yungang art heritage should keep pace with times on the setting of “digital humanity” times, make the most of new research approaches which is given by “digital humanity” and explore a new way of pace transformation of art heritage actively. The research object of this topic is lineage master in space and form and the transformation of promotion and Creativity of Yungang Grotto art heritage. The goal is taking advantage of big data basics and the information sample collection and integration in the context of the full media era. Transferring Yungang Grotto art materially and creatively by making use of the world's advanced "art + science and technology" means, building a new type of modern sapiential museum and explore the construction mode of it and the upgraded version of modern educational functions. approaches which is given by “digital humanity” and explore a new way of pace transformation of art heritage 1 Introduction actively. During the long race against the "disappearance" Yungang Grotto represent the highest level of north royal of cultural relics, the design of the wise exhibition grotto art in the 5th century AD. -

The Social Costs of Marine Litter Along the East China Sea: Evidence from Ten Coastal Scenic Spots of Zhejiang Province, China

Article The Social Costs of Marine Litter along the East China Sea: Evidence from Ten Coastal Scenic Spots of Zhejiang Province, China Manhong Shen 1,2, Di Mao 1, Huiming Xie 2,* and Chuanzhong Li 3 1 School of Economics, Zhejiang University, Hangzhou 310027, China; [email protected] (M.S.); [email protected] (D.M.) 2 School of Business, Ningbo University, Ningbo 315211, China; [email protected] (M.S.); [email protected] (H.X.) 3 Department of Economics, University of Uppsala, 751 20 Uppsala, Sweden; [email protected] * Correspondence: [email protected] Received: 28 February 2019; Accepted: 18 March 2019; Published: 25 March 2019 Abstract: Marine litter poses numerous threats to the global environment. To estimate the social costs of marine litter in China, two stated preference methods, namely the contingent valuation model (CVM) and the choice experiment model (CEM), were used in this research. This paper conducted surveys at ten different beaches along the East China Sea in Zhejiang province in October 2017. The results indicate that approximately 74.1% of the interviewees are willing to volunteer to participate in clean-up programmes and are willing to spend 1.5 days per month on average in their daily lives, which equates to a potential loss of income of USD 1.08 per day. The willingness to pay for the removal of the main types of litter ranges from USD 0.12–0.20 per visitor across the four sample cities, which is mainly determined by the degree of the removal, the crowdedness of the beach and the visitor’s perception. -

A Symbol of Global Protec- 7 1 5 4 5 10 10 17 5 4 8 4 7 1 1213 6 JAPAN 3 14 1 6 16 CHINA 33 2 6 18 AF Tion for the Heritage of All Humankind

4 T rom the vast plains of the Serengeti to historic cities such T 7 ICELAND as Vienna, Lima and Kyoto; from the prehistoric rock art 1 5 on the Iberian Peninsula to the Statue of Liberty; from the 2 8 Kasbah of Algiers to the Imperial Palace in Beijing — all 5 2 of these places, as varied as they are, have one thing in common. FINLAND O 3 All are World Heritage sites of outstanding cultural or natural 3 T 15 6 SWEDEN 13 4 value to humanity and are worthy of protection for future 1 5 1 1 14 T 24 NORWAY 11 2 20 generations to know and enjoy. 2 RUSSIAN 23 NIO M O UN IM D 1 R I 3 4 T A FEDERATION A L T • P 7 • W L 1 O 17 A 2 I 5 ESTONIA 6 R D L D N 7 O 7 H E M R 4 I E 3 T IN AG O 18 E • IM 8 PATR Key LATVIA 6 United Nations World 1 Cultural property The designations employed and the presentation 1 T Educational, Scientific and Heritage of material on this map do not imply the expres- 12 Cultural Organization Convention 1 Natural property 28 T sion of any opinion whatsoever on the part of 14 10 1 1 22 DENMARK 9 LITHUANIA Mixed property (cultural and natural) 7 3 N UNESCO and National Geographic Society con- G 1 A UNITED 2 2 Transnational property cerning the legal status of any country, territory, 2 6 5 1 30 X BELARUS 1 city or area or of its authorities, or concerning 1 Property currently inscribed on the KINGDOM 4 1 the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries. -

CHINA VANKE CO., LTD.* 萬科企業股份有限公司 (A Joint Stock Company Incorporated in the People’S Republic of China with Limited Liability) (Stock Code: 2202)

Hong Kong Exchanges and Clearing Limited and The Stock Exchange of Hong Kong Limited take no responsibility for the contents of this announcement, make no representation as to its accuracy or completeness and expressly disclaim any liability whatsoever for any loss howsoever arising from or in reliance upon the whole or any part of the contents of this announcement. CHINA VANKE CO., LTD.* 萬科企業股份有限公司 (A joint stock company incorporated in the People’s Republic of China with limited liability) (Stock Code: 2202) ANNOUNCEMENT OF UNAUDITED RESULTS FOR THE SIX MONTHS ENDED 30 JUNE 2020 The board of directors (the “Board”) of China Vanke Co., Ltd.* (the “Company”) is pleased to announce the unaudited results of the Company and its subsidiaries for the six months ended 30 June 2020. This announcement, containing the full text of the 2020 Interim Report of the Company, complies with the relevant requirements of the Rules Governing the Listing of Securities on The Stock Exchange of Hong Kong Limited (the “Hong Kong Stock Exchange”) in relation to information to accompany preliminary announcement of interim results. The printed version of the Company’s 2020 Interim Report will be delivered to the holders of H shares of the Company and available for viewing on the websites of the Hong Kong Stock Exchange (www.hkexnews.hk) and of the Company (www.vanke.com) in September 2020. Both the Chinese and English versions of this results announcement are available on the websites of the Company (www.vanke.com) and the Hong Kong Stock Exchange (www.hkexnews.hk). In the event of any discrepancies in interpretations between the English version and Chinese version, the Chinese version shall prevail, except for the financial report, of which the English version shall prevail. -

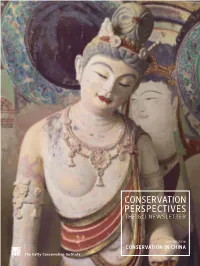

Conservation in China Issue, Spring 2016

SPRING 2016 CONSERVATION IN CHINA A Note from the Director For over twenty-five years, it has been the Getty Conservation Institute’s great privilege to work with colleagues in China engaged in the conservation of cultural heritage. During this quarter century and more of professional engagement, China has undergone tremendous changes in its social, economic, and cultural life—changes that have included significant advance- ments in the conservation field. In this period of transformation, many Chinese cultural heritage institutions and organizations have striven to establish clear priorities and to engage in significant projects designed to further conservation and management of their nation’s extraordinary cultural resources. We at the GCI have admiration and respect for both the progress and the vision represented in these efforts and are grateful for the opportunity to contribute to the preservation of cultural heritage in China. The contents of this edition of Conservation Perspectives are a reflection of our activities in China and of the evolution of policies and methods in the work of Chinese conservation professionals and organizations. The feature article offers Photo: Anna Flavin, GCI a concise view of GCI involvement in several long-term conservation projects in China. Authored by Neville Agnew, Martha Demas, and Lorinda Wong— members of the Institute’s China team—the article describes Institute work at sites across the country, including the Imperial Mountain Resort at Chengde, the Yungang Grottoes, and, most extensively, the Mogao Grottoes. Integrated with much of this work has been our participation in the development of the China Principles, a set of national guide- lines for cultural heritage conservation and management that respect and reflect Chinese traditions and approaches to conservation.