Rush 2013.Pdf

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Midnight Special Songlist

west coast music Midnight Special Please find attached the Midnight Special song list for your review. SPECIAL DANCES for Weddings: Please note that we will need your special dance requests, (I.E. First Dance, Father/Daughter Dance, Mother/Son Dance etc) FOUR WEEKS in advance prior to your event so that we can confirm that the band will be able to perform the song(s) and that we are able to locate sheet music. In some cases where sheet music is not available or an arrangement for the full band is need- ed, this gives us the time needed to properly prepare the music and learn the material. Clients are not obligated to send in a list of general song requests. Many of our clients ask that the band just react to whatever their guests are responding to on the dance floor. Our clients that do provide us with song requests do so in varying degrees. Most clients give us a handful of songs they want played and avoided. Recently, we’ve noticed in increase in cli- ents customizing what the band plays and doesn’t play with very specific detail. If you de- sire the highest degree of control (allowing the band to only play within the margin of songs requested), we ask for a minimum of 100 requests. We want you to keep in mind that the band is quite good at reading the room and choosing songs that best connect with your guests. The more specific/selective you are, know that there is greater chance of losing certain song medleys, mashups, or newly released material the band has. -

2016 ARRL Boxboro Info for Parents.Pages

The ARRL New England Convention at the Holiday Inn, Boxborough, MA September 9-10-11, 2016 Friday Evening DXCC Dinner Saturday Evening Banquet Keynote Speaker David Collingham, K3LP Keynote Speaker Historian Donna Halper The VP8S South Sandwich & South Georgia Heroes of Amateur Radio, Past, Present, and DXpedition Future Social Hour 6PM, Dinner 7PM Social Hour 6PM, Dinner 7PM David Collingham, K3LP, was a co-leader of the fourteen Donna Halper is a respected and experienced media member team that visited South Sandwich and South historian, her research has resulted in many Georgia Islands in February 2016 to put VP8STI & appearances on both radio and TV, including WCVB's VP8SGI on the air. David has participated in dozens of Chronicle, Voice of America, PBS/NewsHour, National DXpeditions as noted on his K3LP.COM website. He will Public Radio, New England Cable News, History be sharing his experiences from his last one with us. Channel, ABC Nightline, WBZ Radio (Boston) and many more. She is the author of six books, including Boston Radio 1920 - a history of Boston radio in words and pictures. Ms. Halper attended Northeastern University in What is the ARRL Boxboro Convention? Boston, where she was the first woman announcer in the school's history. She turned a nightly show in 1968 on The ARRL (American Radio Relay League), a the campus radio station into a successful career in national organization for amateur radio, hosts ham broadcasting, including more than 29 years as a radio conventions across the US each year. Held at the programming -

Apr-May 1980

MODERN DRUMMER VOL. 4 NO. 2 FEATURES: NEIL PEART As one of rock's most popular drummers, Neil Peart of Rush seriously reflects on his art in this exclusive interview. With a refreshing, no-nonsense attitude. Peart speaks of the experi- ences that led him to Rush and how a respect formed between the band members that is rarely achieved. Peart also affirms his belief that music must not be compromised for financial gain, and has followed that path throughout his career. 12 PAUL MOTIAN Jazz modernist Paul Motian has had a varied career, from his days with the Bill Evans Trio to Arlo Guthrie. Motian asserts that to fully appreciate the art of drumming, one must study the great masters of the past and learn from them. 16 FRED BEGUN Another facet of drumming is explored in this interview with Fred Begun, timpanist with the National Symphony Orchestra of Washington, D.C. Begun discusses his approach to classical music and the influences of his mentor, Saul Goodman. 20 INSIDE REMO 24 RESULTS OF SLINGERLAND/LOUIE BELLSON CONTEST 28 COLUMNS: EDITOR'S OVERVIEW 3 TEACHERS FORUM READERS PLATFORM 4 Teaching Jazz Drumming by Charley Perry 42 ASK A PRO 6 IT'S QUESTIONABLE 8 THE CLUB SCENE The Art of Entertainment ROCK PERSPECTIVES by Rick Van Horn 48 Odd Rock by David Garibaldi 32 STRICTLY TECHNIQUE The Technically Proficient Player JAZZ DRUMMERS WORKSHOP Double Time Coordination by Paul Meyer 50 by Ed Soph 34 CONCEPTS ELECTRONIC INSIGHTS Drums and Drummers: An Impression Simple Percussion Modifications by Rich Baccaro 52 by David Ernst 38 DRUM MARKET 54 SHOW AND STUDIO INDUSTRY HAPPENINGS 70 A New Approach Towards Improving Your Reading by Danny Pucillo 40 JUST DRUMS 71 STAFF: EDITOR-IN-CHIEF: Ronald Spagnardi FEATURES EDITOR: Karen Larcombe ASSOCIATE EDITORS: Mark Hurley Paul Uldrich MANAGING EDITOR: Michael Cramer ART DIRECTOR: Tom Mandrake The feature section of this issue represents a wide spectrum of modern percussion with our three lead interview subjects: Rush's Neil Peart; PRODUCTION MANAGER: Roger Elliston jazz drummer Paul Motian and timpanist Fred Begun. -

Rush Three of Them Decided to - Geddy Recieved a Phone Reform Rush but Without Call from Alex

history portraits J , • • • discography •M!.. ..45 I geddylee J bliss,s nth.slzers. vDcals neil pearl: percussion • alex liFesDn guitars. synt.hesizers plcs: Relay Photos Ltd (8); Mark Weiss (2); Tom Farrington (1): Georg Chin (1) called Gary Lee, generally the rhythm 'n' blues known as 'Geddy' be combo Ogilvie, who cause of his Polish/Jewish shortly afterwards also roots, and a bassist rarely changed their me to seen playing anything JUdd, splitting up in Sep other than a Yardbirds bass tember of the sa'l1le year. line. John and Alex, w. 0 were In September of the same in Hadrian, contacted year The Projection had Geddy again, and the renamed themselves Rush three of them decided to - Geddy recieved a phone reform Rush but without call from Alex. who was in Lindy Young, who had deep trouble. Jeff Jones started his niversity was nowhere to be found, course by then. In Autumn although a gig was 1969 the first Led Zeppelin planned for that evening. LP was released, and it hit Because the band badly Alex, Geddy an(i John like needed the money, Geddy a hammer. Rush shut them helped them out, not just selves away in their rehe providing his amp, but also arsal rooms, tUfned up the jumping in at short notice amp and discovered the to play bass and sing. He fascination of heavy was familiar with the Rush metaL. set alreadY, as they only The following months played well-known cover were going toJprove tough versions, and with his high for the three fYoung musi voice reminiscent of Ro cians who were either still bert Plant, he comple at school or at work. -

Rolling Stone Magazine's Top 500 Songs

Rolling Stone Magazine's Top 500 Songs No. Interpret Title Year of release 1. Bob Dylan Like a Rolling Stone 1961 2. The Rolling Stones Satisfaction 1965 3. John Lennon Imagine 1971 4. Marvin Gaye What’s Going on 1971 5. Aretha Franklin Respect 1967 6. The Beach Boys Good Vibrations 1966 7. Chuck Berry Johnny B. Goode 1958 8. The Beatles Hey Jude 1968 9. Nirvana Smells Like Teen Spirit 1991 10. Ray Charles What'd I Say (part 1&2) 1959 11. The Who My Generation 1965 12. Sam Cooke A Change is Gonna Come 1964 13. The Beatles Yesterday 1965 14. Bob Dylan Blowin' in the Wind 1963 15. The Clash London Calling 1980 16. The Beatles I Want zo Hold Your Hand 1963 17. Jimmy Hendrix Purple Haze 1967 18. Chuck Berry Maybellene 1955 19. Elvis Presley Hound Dog 1956 20. The Beatles Let It Be 1970 21. Bruce Springsteen Born to Run 1975 22. The Ronettes Be My Baby 1963 23. The Beatles In my Life 1965 24. The Impressions People Get Ready 1965 25. The Beach Boys God Only Knows 1966 26. The Beatles A day in a life 1967 27. Derek and the Dominos Layla 1970 28. Otis Redding Sitting on the Dock of the Bay 1968 29. The Beatles Help 1965 30. Johnny Cash I Walk the Line 1956 31. Led Zeppelin Stairway to Heaven 1971 32. The Rolling Stones Sympathy for the Devil 1968 33. Tina Turner River Deep - Mountain High 1966 34. The Righteous Brothers You've Lost that Lovin' Feelin' 1964 35. -

Geddy Lee DI-2112 Signature

POWER REQUIREMENTS •Utilizes two (2) standard 9V alkaline batteries (not included). NOTE: Input jack activates batteries. To conserve energy, unplug when not in use. Power Consumption: approx. 55mA. Geddy Lee Signature •USE DC POWER SUPPLY ONLY! Failure to do so may damage the unit and void warranty. DC Power Supply Specifications: SansAmp DI-2112 -18V DC regulated or unregulated, 100mA minimum; -2.1mm female plug, center negative (-). •Refer to “Power Considerations” in Noteworthy Notes on page 8. WARNINGS: • Attempting to repair unit is not recommended and may void warranty. • Missing or altered serial numbers automatically void warranty. For your own protection: be sure serial number labels on the unit’s back plate and exterior box are intact, and return your warranty registration card. ONE YEAR LIMITED WARRANTY. PROOF OF PURCHASE REQUIRED. Manufacturer warrants unit to be free from defects in materials and workmanship for one (1) year from date of purchase to the original pur - chaser and is not transferable. This warranty does not include damage resulting from accident, misuse, abuse, alteration, or incorrect current or voltage. If unit becomes defective within warranty period, Tech 21 will repair or replace it free of charge. After expiration, Tech 21 will repair defective unit for a fee. ALL REPAIRS for residents of U.S. and Canada: Call Tech 21 for Return Authorization Number . Manufacturer will not accept packages without prior authorization, pre-paid freight (UPS preferred) and proper insurance. FOR PERSONAL ASSISTANCE & SERVICE: Contact Tech 21 weekdays from 9:00 AM to 5:00 PM, EST. Hand-built in the U.S.A. -

265 Edward M. Christian*

COPYRIGHT INFRINGEMENT ANALYSIS IN MUSIC: KATY PERRY A “DARK HORSE” CANDIDATE TO SPARK CHANGE? Edward M. Christian* ABSTRACT The music industry is at a crossroad. Initial copyright infringement judgments against artists like Katy Perry and Robin Thicke threaten millions of dollars in damages, with the songs at issue sharing only very basic musical similarities or sometimes no similarities at all other than the “feel” of the song. The Second Circuit’s “Lay Listener” test and the Ninth Circuit’s “Total Concept and Feel” test have emerged as the dominating analyses used to determine the similarity between songs, but each have their flaws. I present a new test—a test I call the “Holistic Sliding Scale” test—to better provide for commonsense solutions to these cases so that artists will more confidently be able to write songs stemming from their influences without fear of erroneous lawsuits, while simultaneously being able to ensure that their original works will be adequately protected from instances of true copying. * J.D. Candidate, Rutgers Law School, January 2021. I would like to thank my advisor, Professor John Kettle, for sparking my interest in intellectual property law and for his feedback and guidance while I wrote this Note, and my Senior Notes & Comments Editor, Ernesto Claeyssen, for his suggestions during the drafting process. I would also like to thank my parents and sister for their unending support in all of my endeavors, and my fiancée for her constant love, understanding, and encouragement while I juggled writing this Note, working full time, and attending night classes. 265 266 RUTGERS UNIVERSITY LAW REVIEW [Vol. -

Orpe=Civ= V=Kfdeq Italic Flybynightitalic.Ttf

Examples Rush Font Name Rush File Name Album Element Notes Working Man WorkingMan.ttf Rush Logo, Album/Song RUSH Working Man Titles Fly By Night, regular and FlyByNightregular.ttf. orpe=civ=_v=kfdeq italic FlyByNightitalic.ttf Caress Of Steel CaressOfSteel.ttf Rush Logo, Album Title Need to Photoshop to get the correct style RUSH CARESS OF STEEL Syrinx Syrinx.ttf Rush Logo, Album/Song RUSH 2112 Titles ALL THE WORLD'S A STAGE (core font: Arial/Helvetica) Cover text Arial or Helvetica are core fonts for both Windows and Mac Farewell To Kings FarewellToKings.ttf Rush Logo, Album/Song Rush A Farewell To Kings Titles Strangiato Strangiato.ttf Rush Logo Similar to illustrated "Rush" Rush Hemispheres Hemispheres.ttf Album Title Custom font by Dave Ward. Includes special character for "Rush". Hemispheres | RUSH THROUGH TIME RushThroughTime RushThroughTime.ttf Album Title RUSH Jacob's Ladder JacobsLadder.ttf Rush Logo Hybrid font PermanentWaves PermanentWaves.ttf Album Title permanent waves Moving Pictures MovingPictures.ttf Rush Logo, Album Title Same font used for Archives, Permanent Waves general text, RUSH MOVING PICTURES Moving Pictures and Different Stages Exit...Stage Left Bold ExitStageLeftBold.ttf Rush Logo RUSH Exit...Stage Left ExitStageLeft.ttf Album Title Exit...Stage Left SIGNALS (core font: Garamond) Album Title Garamond, a core font in Windows and Mac Grace Under Pressure GraceUnderPressure.ttf Rush Logo, Album Title, Upper Case character set only RUSH GRACE UNDER PRESSURE Song Titles RUSH Grand Designs GrandDesigns.ttf Rush Logo RUSH Grand Designs Lined GrandDesignsLined.ttf Alternate version Best used at 24pt or larger Power Windows PowerWindows.ttf Album Title, Song Titles POWER WINDOWS Hold Your Fire Black HoldYourFireBlack.ttf Rush Logo Need to Photoshop to get the correct style RUSH Hold Your Fire HoldYourFire.ttf Album Title, Song Titles HOLD YOUR FIRE A Show Of Hands AShowofHands.ttf Song Titles Same font as Power Windows. -

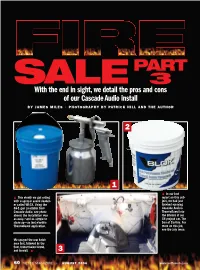

With the End in Sight, We Detail the Pros and Cons of Our Cascade Audio Install by JAMES MILES • PHOTOGRAPHY by PATRICK HILL and the AUTHOR

PART SALE 3 With the end in sight, we detail the pros and cons of our Cascade Audio install BY JAMES MILES • PHOTOGRAPHY BY PATRICK HILL AND THE AUTHOR 2 1 L In our last L This month we got rolling report on this sub- with a spray-in sound deaden- ject, we had just er called VB-1X. Using the finished spraying SG-1 gun (available from Cascade Audio’s Cascade Audio, see photo ThermaGuard into above) the installation was the interior of our as easy—and as simple to C4 project car, The clean up—as last month’s Son of Zombie. For ThermaGuard application. more on this job, see the July issue. We sprayed the rear hatch area first, followed by the floor, transmission tunnel, and firewall. L 3 60 VETTE MAGAZINE • AUGUST 2006 www.vetteweb.com the July issue, we lined the inside of our project ’87 with Cascade Audio’s ThermaGuard to help keep the heat out of Inthe cockpit. This month, we took the install to the next level, with Cascade’s VB-1X, a spray-on sound deadener that’s similar to a truck-bed coat- ing. The volume differences were instantly notice- able, and thanks to a Radio Shack-issue decibel meter and the Neil Peart drum solo “Der Trommler,” we know the extent of the changes. Following the final coat of VB-1X, we went a step further and added some of Cascade’s V-Max material to the trouble areas inside the C4— namely, the transmission tunnel, rear hatch, and B-pillar. -

No Permanent Waves Bbbbbbbbbbbbbbbbbbbbbbb

No Permanent Waves bbbbbbbbbbbbbbbbbbbbbbb No Permanent Waves Recasting Histories of U.S. Feminism EDITED BY NANCY A. HEWITT bbbbbbbbbbbbbbbbbbbbbbb RUTGERS UNIVERSITY PRESS NEW BRUNSWICK, NEW JERSEY, AND LONDON LIBRARY OF CONGRESS CATALOGING-IN-PUBLICATION DATA No permanent waves : recasting histories of U.S. feminism / edited by Nancy A. Hewitt. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 978‒0‒8135‒4724‒4 (hbk. : alk. paper)— ISBN 978‒0‒8135‒4725‒1 (pbk. : alk. paper) 1. Feminism—United States—History. 2. First-wave feminism—United States. 3. Second-wave feminism—United States. 4. Third-wave feminism—United States. I. Hewitt, Nancy A., 1951‒ HQ1410.N57 2010 305.420973—dc22 2009020401 A British Cataloging-in-Publication record for this book is available from the British Library. This collection copyright © 2010 by Rutgers, The State University For copyrights to previously published pieces please see first note of each essay. Pieces first published in this book copyright © 2010 in the names of their authors. All rights reserved No part of this book may be reproduced or utilized in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, or by any information storage and retrieval system, without written permission from the publisher. Please contact Rutgers University Press, 100 Joyce Kilmer Avenue, Piscataway, NJ 08854‒8099. The only exception to this prohibition is “fair use” as defined by U.S. copyright law. Visit our Web site: http://rutgerspress.rutgers.edu Manufactured in the United States of America To my feminist friends CONTENTS Acknowledgments xi Introduction 1 NANCY A. HEWITT PART ONE Reframing Narratives/Reclaiming Histories 1 From Seneca Falls to Suffrage? Reimagining a “Master” Narrative in U.S. -

GEDDY EASTON 'LEE Master of the ,Hook Bass + Power = Progressive Pop ERIC 'JOHNSON the Wat M Tone of a TEXAS TWISTER

- 802135 MAY 1986 $2.50 Inside This Issue: A SPECIAL Billy Idol's STEVE STEVENS (not -so-secret) CASSETTE Secret See Page 54 Weapon For Details THE CARS' RUSH'S ELLIOT GEDDY EASTON 'LEE Master Of The ,Hook Bass + Power = Progressive Pop ERIC 'JOHNSON The Wat m Tone Of A TEXAS TWISTER PLUS: Lonnie Mack Albert Collins Roy Buchanan , 'Tony MacAlpine o Curtis Mayfield MORE BASS, MORE SPACE IN THE MODERN WORLD Power Windows is the best Rush albutn in years because the band ----and the bass---- has returned to the roots of its sound ... tneticulously. BY JOHN SWENSON It has been a long, vertiginous and damn exciting roller coaster ride for Rush over the past decade-and-a-half. The group has gone from being unabashed Led Zeppelinites to kings of the concept album to the thinking man's heavy metal band to an uneasy combination of eighties record ing styles and seventies relentlessness. One thing Rush has never done is rest on its collective laurels-bassist Geddy Lee, guitarist Alex Lifeson and drummer Neil Peart have always been the first to point out the band's shortcomings when they feel legitimate deficiencies have surfaced. Accordingly, Lee was quick to admit his dissatisfaction with the band's last album, Grace Under Pressure , even though the record , which went platinum, has con solidated the band's position as one of Mercury/Polygram's most important acts. "We realized with Grace Under Pres sure ," said Lee on completion of the new album , Power Windows, "that we were not a techno-pop band. -

ATTENTION All Planets of the Solar Federationii'

i~~30 . .~,.~.* ~~~ Welcome to the latest issue of 'Spirit'. From this issue we are reverting to quarterly publication, hopefully next year we will go back to bi-monthly, once the band are active again. Please join me in welcoming Stewart Gilray aboard as assistant editor. Good luck to Neil Elliott with the Dream Theater fan zine he is currently producing, Neil's address can be found in the perman ant trades section if you are interested. Alex will be appearing at this years Kumbaya Festival in Toronto on the 2nd September, as .... with previous years this Aids benefit show will feature the cream of Canadian talent, Vol 8 No 1 giving their all for a good cause. Ray our North American corespondent will be attending Published quarterly by:- the show (lucky bastard) he will be fileing a full report (with pictures) for the next issue, won't you Ray? Mick Burnett, Alex should have his solo album (see interview 23, Garden Close, beginning page 3) in the shops by October. Chinbrook Road, If all goes well the album should be released Grove Park, in Europe at the same time as North America. London. Next issue of 'Spirit' should have an exclus S-E-12 9-T-G ive interview with Alex telling us all about England. the album. Editor: Mick Burnett The band should be getting back together to Asst Editor: Stewart Gilray begin work writing the new album in September. Typist: Janet Balmer Recording to commence Jan/Feb of next year Printers: C.J.L. with Peter Collins once more at the helm.