A Survey of Legislative Attempts at Architectural and Historical

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

TÁBOR, Czech Republic (September 2019)

TÁBOR, Czech republic (September 2019) Project Erasmus +“ Educating Innovative and Creative Citizens with 5 European partnership schools.This is the meeting-about students from foreign countrie- s,making contacts,breaking the barriers and broadening their horizons in different fields. Each project is different and unique. The goals of meeting are different On Friday we visited Třeboň. It´s a famous historic as well. This year we have been“ town and a fishing centre and we enjoyed it. However hosts“ and the theme was“ Wa- our first stop weren´t lakes but Schwanzenbergs´ ter and historical sites.“The me- tomb. After that we went to the lake Svět (translated eting was held from 11 th- 16 th World) and to the centre of the town. Then we had September in 2019.The main goal a trip on a boat around Svět, which finished our trip was to present presentations in in Třeboň. On Saturday we visited Táborská setkání English.Each foreign group has with students from our partner schools (Konstanz, prepared their own presentations Skofia Loka, Wels and Pezszyna). Sunday was our back at home. The topic was „ the last day, we visited Kutná Hora. The weather was main function of water at histo- fantastic. We stopped at Kostnice, which we know is rical sites.“The next goal was to ossuary in English.We stayed there a little and chec- make short videos during the pro- ked out the city and the cemetary. After that we went ject ´s days. to the castle of Saint John the Baptist. It was very in- teresting. -

Kinsky Trio Prague

KINSKY TRIO PRAGUE Veronika Böhmová - Piano Lucie Sedláková H ůlová - Violin Martin Sedlák - Cello Founded in 1998, the KINSKY TRIO PRAGUE is one of the outstanding Czech chamber ensembles. Since 2004 the Trio has had the honour of bearing the name ‘KINSKY’ by kind permission of the aristocratic Czech family from Kostelec nad Orlicí. The Trio studied at the Academy of Music in Prague under Václav Bernášek, cellist of the Kocian Quartet and has taken part in several master classes (e.g. with the Guarneri Trio and the Florestan Trio). The Kinsky’s international career has taken them all over Europe (Austria, Germany, Switzerland, Italy, Spain, Belgium, England, France), the U.S., Canada, Mexico and also the Seychelles. In 2007 - 2009 the Kinsky Trio Prague organized its own series of chamber concerts at the Stone Bell House, an historic inn on the Old Town Square in their home city of Prague. They regularly record for Czech Radio, and their concerts have also been broadcast in Mexico and the U.S. Since 2009 the Kinsky Trio Prague regularly record CDs for the French label Praga Digitals (distributed by Harmonia Mundi). Their recording of complete piano trios by Bohuslav Martin ů has been warmly recommended by international music critics (Diapason, Gramophone, Classica, Harmonie, etc.). The other CDs include compositions by Czech composers Foerster, Novák, Janá ček and Fibich, and less known Russian trios by Borodin, Rimsky Korsakov and Arensky. …The Kinsky Trio catch the spirit of both early sets very neatly in performances of great charm and dexterity. ... Gramophone 10/2009 …Kinsky Trio Prague resurrects these admirable pages with a communicative verve at each moment. -

Hussite Prague Master Jan Hus Saturday 4Th July Centres Czech History Is Full of Gripping and Surprising Twists and Turns

Master Jan Hus In the footsteps of A day with Jan Hus on Prague City Tourism Information & Services in Six Tourist Information Hussite Prague Master Jan Hus Saturday 4th July Centres Czech history is full of gripping and surprising twists and turns. When Summer in Prague Jan Hus was burned at the stake in Constance for his views and – Old Town Hall – Staroměstské náměstí 1 criticism of the Catholic Church 600 years ago on 6th July 1415 none To mark the 600 years since the events that led Prague City Tourism have prepared a day full of fun – Rytířská Street 31 (from August in Rytířská 12, corner of Na Můstku) suspected what profound changes Czech society would undergo thanks to the burning of Hus in 1415, let us follow in his and surprises while getting to know the persona – Wenceslas Square (upper part) – corner of Štěpánská Street 2015 to him in the following decades. His name came to stand for principled footsteps. One of the most important personages of Master Jan Hus and the Prague sites tied to him. – Lesser Town Bridge Tower defi ance. This theologian, preacher and Master of Prague University – Václav Havel Airport Prague – Terminal 1 and Terminal 2 was to be one of the leading religious authorities, whose ideas spread of Czech history will lead us via matchless and Would you like to meet the ghost of Jan Želivský or tel. +420 221 714 714 and e-mail: [email protected] beyond Czech borders. The European reformation of the 16th century historically distinctive Prague sites. and get to know more about Czech Hussite past? owed much to what Hus called for. -

2015 Annual Report Prague City Tourism CONTENTS

2015 Annual Report Pražská informační služba – Prague City Tourism 2015 Annual Report Arbesovo náměstí 70/4 / Praha 5 / 150 00 / CZ www.prague.eu Prague City Tourism 2015 Annual Report Prague City Tourism CONTENTS 4 INTRODUCTION BY THE CEO 34 PUBLISHING 6 PROFILE OF THE ORGANIZATION 36 OLD TOWN HALL About Us Organization Chart 38 EDUCATION DEPARTMENT Prague Cultural History Walks 10 MARKETING AND PUBLIC RELATIONS Tour Guide Training and Continuing Education Online Campaign The Everyman's University of Prague Facebook and other Social Media Marketing Themes and Campaigns 40 RESEARCH: PRAGUE VISITORS POLL International Media Relations and Press Trips Domestic Media Relations 44 2015 IN PRAGUE CITY TOURISM FIGURES Partnerships and Collaborations Exhibitions, Trade Shows and Presentations 45 PRAGUE CITY TOURISM FINANCES AND ECONOMIC RESULTS IN 2015 24 VISITOR SERVICES 50 TOURISM IN PRAGUE 2015 Tourist Information Centres Domestic and International Road Shows 56 PRAGUE CITY TOURISM: 2016 OUTLOOK Prague.eu Web Site E-Shop Guide Office INTRODUCTION BY THE CEO From Visions to Results An inseparable part of our overall activities was supporting foreign media, 2015 has been a year of significant professional journalists and bloggers, as well as tour operators and travel agents visiting our advancements for our organization. Its new destination. We provided them with special-interest or general guided tours and corporate name – Prague City Tourism – entered shared insights on new and noteworthy attractions that might be of interest to the public consciousness and began to be used their readers and clients, potential visitors to Prague. by the public at large. A community of travel and tourism experts has voted me Person of the Year, Record numbers of visitors to our capital city also requires significant informational and I was among the finalists of the Manager resources, whether printed (nearly 1,400,000 copies of publications in 13 language of the Year competition. -

Objevování Zlaté Prahy AJ

4 steps: This symbol tells you to read about Prague´s history and its legends. This symbol tells you where to go. This symbol tells you to answer our questions. The answers must be written in to a special form. This symbol tells you to complete the rows of our crossword puzzle. Our recommendations: - Be fair! You are representing your school. - Remember that you are a team! - Look around carefully! - Use your brain:) - Don´t wait for your friends. You´ll make it without their help. - Use your map. - And play... Agentura Wenku s.r.o. | Na Hanspaulce 799/37 | 160 00 Praha 6, Dejvice | IČ: 28431375 tel.: +420 222 365 709 | mobil: +420 724 623 660 | [email protected] | www.wenku.cz EXPLORING OF THE GOLDEN PRAGUE p. 2 POWDER TOWER (PRAŠNÁ BRÁNA): Powder Tower was built by Matěj Rejsek in 1475. It got its present name in the 17th century when it was used to store gunpowder . Down Celetná street to the Old Town Square. CELETNÁ STREET (CELETNÁ ULICE): one of the oldest streets in Prague. Do you know why it is called Celetná? Because of bread rolls! They were first baked here in the Middle Ages and they were called „calty“. Questions A OLD TOWN SQUARE (STAROMĚSTSKÉ NÁMĚSTÍ): Prague's heart since the 12th century. The Old Town Square has been the scene of great events, both glorious and tragic. One of those tragic was an execution of the Czech lords who had led the rebellion against Emperor Ferdinand II (they were defeated in a battle at Bílá hora in 1620). -

Prague: the Jewel of Eastern Europe 28° 32° June 4-12, 2021 80° 79° 78° 77°

Prague: The Jewel of Eastern Europe 28° 32° June 4-12, 2021 80° 79° 78° 77° Prague, capital city of the Czech Republic, is bisected by 32° 36° 76° the Vltava River. Nicknamed “the City of a Hundred Spires,” it is known for its Old Town Square, the heart of its historic core, with colorful baroque buildings, Gothic churches and the medieval Astronomical Clock, which gives an animated hourly show. Completed in 1402, the iconic, pedestrian Charles Bridge is lined with statues of Catholic saints, recalling its past as the capital of the Holy Roman Empire. The Czech Republic is one of Europe’s recent success stories. Since the fall of the Soviet Union, it has celebrated its freedom and independence with wide sweeping reforms and a new-found economic prosperity. Much of this progress reached its peak when, on May 1st 2004, they were admitted to membership of the European Union. Much of its charm, however, lies in the history and cultural wealth that its ancient position in Europe created. While our tour focuses on the capital city of Prague, we will also explore the rural side of the country with excursions to the provinces and a dinner cruise along the Vltava River, that for so long dominated the region’s commerce. This then is truly one of the jewels of Eastern Europe. Prague Program Highlights reserve early! • Welcome dinner evening of arrival; • Walking tour of Prague around Wenceslas Square and the Old Town with its famous Astronomical Clock atop the 14th-century Town Hall. We’ll continue through the Jewish $3,699 Ghetto to St. -

Old Town Square (Staromestske Namesti) Jan Hus Memorial

Old Town Square (Staromestske Namesti) in town. Behind the Tyrn Church is a gorgeously restored medieval courtyard called Ungelt. The row of pastel houses in front of Tyn Church has a mixture of Gothic, Renaissance, and Baroque facades. To the right of these buildings, shop-lined Celetna street leads to a square called Ovocny Trh (with the Estates Theatre and Museum of Czech Cubism, and beyond that, to the Municipal House and Powder Tower in the New Town. Continue spinning right until you reach the pointed 250-foot-tall spire marking the 14th-century OldTown Hall Across the square from the Old Town Hall (opposite the Astronomical Clock), touristy Melantrichova street leads directly to the New Town's Wenceslas Square passing the craft-packed Havelski Market along the way. Twenty-Seven Crosses Embedded in the pavement at the base of the Old Town Hall tower (near the snack stand), you'll see white inlaid crosses marking the spot where 27 Protestant nobles, merchants, and intellectuals were beheaded in 1621 after rebelling against the Catholic Hapsburgs. Today the sacred soil is home to a hot-dog vendor, and few notice the crosses in the pavement. Astronomical Clock ▲▲Join the gang for the striking of the hour on the Town Hall clock worth (daily 8:00-21:00). Two outer rings show the hour: Bohemian time (gold Gothic numbers on black background, counts from sunset-find the zero, between 23 and l...supposedly the time of tonight's sunset) and modern time (24 Roman numerals, XII at the top being noon, XII at the bottom being midnight). -

Christmas Markets December 7-14, 2020

Christmas Markets December 7-14, 2020 Prague walking tour & & Christmas markets Walking tour of Cesky Krumlov & time at the Christmas markets Vienna walking tour & Christmas markets Schloss Hof tour & Christmas market Walking tour of Bratislava & time at the Christmas markets Budapest city tour & Christmas markets Prague Cesky Krumlov DAY 1 MONDAY, DECEMBER 7 FLIGHT TO PRAGUE, CZECH REPUBLIC Today we will meet at the Des Moines airport and sit back, relax, and enjoy our flight to Prague, Czech Republic! DAY 2 TUESDAY, DECEMBER 8 PRAGUE, CZECH REPUBLIC Welcome to Prague, the capital of the Czech Republic. We will be met by our guide and motorcoach for the short drive to our centrally located hotel. After settling in, we will depart on a city walking tour from Prague’s Old Town to Charles Bridge. Highlights will include Wenceslas Square, Powder Gate, and Old Town Square. The heart of the city’s historic core, Old Town Square is filled with colorful Baroque buildings, Gothic churches, and the medieval Astronomical Clock that offers an animated hourly show. The remainder of the day is yours to explore the festive atmosphere of the Prague Christmas markets. The main markets are located in Old Town Square and Wenceslas Square, with smaller markets scattered around the city. Wander among the brightly decorated wooden huts filled with handmade crafts ranging from ceramics, jewelry, and wooden toys to embroidered lace, scented candles, and dolls. For dinner on your own, savor local food and drink prepared fresh at the markets. Roasted ham, barbequed sausages, Hungarian flatbread topped with garlic and cheese, spicy gingerbread, Czech beers, and honey wine are all popular market foods and beverages! DAY 3 WEDNESDAY, DECEMBER 9 PRAGUE, CZECH REPUBLIC (BL) Following breakfast, we’ll continue exploring Prague on foot. -

Humanitas Spring 2003

Humanities and Modern Culture humanitas Spring 2003 The Prague Field School and the Travel Study Award —Jerry Zaslove In 2002 The Institute for the Humanities provided two stipends to assist humanities students to attend the Prague Field School. The program is organized through the Office of International and Exchange Student Services and the Humanities Department. In this eighth year of the credit program with Charles University, twenty students were resident in Prague for eight weeks of in-depth study of Central European culture, art and society. The program includes Keir Niccol courses in language, art history, film, literature and Shades of Apprehension political science. In two short essays, Tim Came and —Keir Niccol Keir Niccol— SFU undergraduates and recipients of Driving away from the airport and down an unnamed the stipends—reflect on aspects of their experience highway, more like a byway, the bus veers around a corner into what I surmise to be a suburb. Rolling down the small and their encounters with the contemporary road, I gape at the brown and tan stucco residences on European world and its legacies. Information about either side, trying to glean as much as possible from these first few, crucial moments of fatigue-filtered, jet-lagged this program can be obtained through the Office impression. Rounding the road’s arc, I glance to my left and of International and Exchange Student Services. notice a single slender figure atop a pillar. The pillar’s grey stone culminates in a same-coloured nymph, balancing in Information about the Travel Study Award can be a moment of stride upon one nimble, slight leg. -

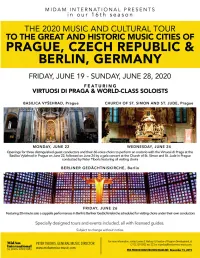

Published on February 11, 2019; Disregard All Previous Documents 1

Subject to change without notice; Published on February 11, 2019; disregard all previous documents 1 Subject to change without notice; Published on February 11, 2019; disregard all previous documents 2 Subject to change without notice; Published on February 11, 2019; disregard all previous documents 3 Subject to change without notice; Published on February 11, 2019; disregard all previous documents 4 2020 Music Tour to Prague and Berlin Registration Deadline: November 15, 2020 Two performances in The Basilica Vyšehrad and The Church of St. Simon and St. Jude On Monday, June 22 and Wednesday, June 24 Mozart’s Vesperae solennes de confessore, K. 339 Earl Rivers, conductor College-Conservatory of Music University of Cincinnati, Ohio And Director of Music Knox Presbyterian Church, Cincinnati, Ohio Virtuosi di Praga Oldřich Vlček, Artistic Director & World-class soloists PLUS Friday, June 26 An a cappella solo performance opportunity by visiting choirs In Berliner Gedächtniskirche A minimum of three groups must agree to perform for this concert to go forward. The Basilica Vyšehrad The Church of St. Simon and St. Jude Berliner Gedächtniskirche MidAm International, Inc. · 39 Broadway, Suite 3600 (36th FL) · New York, NY 10006 Tel. (212) 239-0205 · Fax (212) 563-5587 · www.midamerica-music.com Subject to change without notice; Published on February 11, 2019; disregard all previous documents 5 2020 MUSIC TOUR TO PRAGUE AND BERLIN: Itinerary Day 1 – Friday, June 19, 2020 – Arrive Prague • Arrive in Prague. MidAm International, Inc. staff and The Columbus Welcome Management staff will meet you at the airport and transfer you to Hotel Don Giovanni (http://www.hotelgiovanni.cz/en) for check-in. -

Prague Royal Route

PRAGUE ROYAL ROUTE POWDER GATE – OLD TOWN SQUARE – CHARLES BRIDGE – LESSER QUARTER SQUARE – NERUDOVA STREET – PRAGUE CASTLE Exit Courtyard by Marriott Prague City A and get the tram #15 to Masarykovo nádraží. Then pass the Republic Square ands there is the Municipal House. s Powder Gate B A monumental gatefF leading into the Old Town. The Gothic building dating from 1475 was designed by MatěCj Rejsek. It was used as a gunpowder storage facility. At the end of the nineteenth century it was rebuilt into its present form by J. Mocker. Old Town Square BC Old Town City Hall, theC Church of Our Lady before Týn, House at the Stone Bell, Kinský Palace, St Nicholas Church and the Jan Hus Memorial can all be found on the square. You will not regret a climb to the top of the Old Town Hall tower. The view of the square and beyond is spectacular. Old Town City Hall C The Old Town City Hall offers two tours. You can climb up the stairs to the Town Hall Tower and enjoy a beautiful view of Prague’s historical centre from a height of almost 70 meters. The second tour will take you through the city hall’s interior (a chapel with apostles, historical halls and a Romanesque-Gothic underground). No less interesting is the city hall’s exterior, dominated by the remarkable Old Town Astronomical Clock. Charles Bridge D A walk on the Charles Bridge will present the interesting history of this oldest preserved connecting line between the two Prague embankments. We recommend strolling across it at night to enjoy the magnificent view of the Prague Castle all lit up. -

Ernst Mach and Wolfang Pauli's Ancestors in Prague

Ernst Mach and Wolfgang Pauli's Ancestors in Prague By Frantisek Smutny Summary 77;c Siviss p/iy.sici.sl JFbZ/gareg PauZi ^7900—7958,1 descends /rom a nolaZde Jewis/i /amZZy o/ /»(/iZf'.sZier.s and èooZcseZZers at Prague. TZiis essay presents /uogrop/»'caZ eZata and Prague /ortunes o/ Ziis /atZier, grantZ/atZier and great- grand/atZier. 7 /te roots o//riendsZttp Zietween ZFoZ/gang PauZi's /atZier and tZie JamiZy ofErnst MaeZi, tZien pro/es.sor at tZie unZrersZty o/Prague, are documented and a Z^potZiests is suggested concerning motives tZiat induced JFoZ/ PascZieZes, JFoZJgang PauZi's/atZier, to cZioosejust "PauZi" as Ziis new surname. "77iepast is Ziead-turning" KareZ CapeZc Preamble In view of a biography of the most famous Swiss physicist after Einstein, Wolfgang Pauli (1900—1958), the undersigned planned to do some research on Pauli's grandfather in Prague while visiting in spring 1986 for a physics meeting to be held in Liblice. To this end I had asked the organizer of this meeting, Dr. Y. Dvorak from the Czechoslovak Aca- demy of Sciences, in late 1985 whether he could propose somebody to help me in the mentioned task. Dr. Dvorak's proposition of a colleague of his was a very lucky one, and I am most grateful to him. Indeed, the very first letter that Dr. Frantisek Smutny wrote me on 28 January 1986, in which he expressed his surprise at learning that Pauli's family had lived in Prague, already contained everything I had wished to find out. The following essay, however, contains much more.