State of Iowa Property Assessment Appeal Board

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Schedule 6 2-2012.Indd

Weather, special events and traffic conditions may alter service. #6 WEST 9TH-DOUGLAS Route 6 Check out SATURDAY & SUNDAY SERVICE W. 9th/DOUGLAS–Merle Hay Mall www.ridedart.com Service from Southridge Mall to Downtown, Broadlawns Hospital, Harding Hills, INDIANOLA–Southridge Mall Veterans Hospital, Hay Market Mall and Merle Hay Mall Saturday & Sunday Service N NORTHBOUND Accessible and Leave Leave Leave Arr/Lv Leave Leave Leave Arrive Schedules South SE 14th & Hartford & W 6th & 9th & Hickman Douglas & Merle Hay Maps for all other routes Ridge Indianola Indianola Walnut University & 18th L. Beaver Mall All Trips - - - - - - - - - - - - 7:45 7:50 7:55 8:01 8:10 AM 8:21 8:31 8:37 * 8:42/45 8:50 8:55 9:01 9:10 9:19 9:30 9:36 * 9:42/45 9:50 9:55 10:01 10:10 10:18 10:30 10:36 * 10:42/45 10:50 10:55 11:01 11:11 Latest information about 11:18 11:30 11:36 * 11:42/45 11:50 11:55 12:01 12:11 DART Services PM 12:18 12:30 12:36 * 12:42/45 12:50 12:55 1:01 1:11 and changes 1:18 1:30 1:36 * 1:42/45 1:50 1:55 2:01 2:11 2:18 2:30 2:36 * 2:42/45 2:50 2:55 3:01 3:11 3:18 3:30 3:36 * 3:42/45 3:50 3:55 4:01 4:11 4:18 4:30 4:36 * 4:42/45 4:50 4:55 5:01 5:11 5:11 5:23 5:29 5:35 TO GARAGE - - - - - - - - - - - - Employer Support #6 INDIANOLA Program SATURDAY & SUNDAY SERVICE Currently, around 60 organizations Service from Hay Market Mall & Merle Hay Mall to Veterans Hospital, Harding Hills, in the Des Moines area offer this Broadlawns Hospital, Downtown and Southridge Mall benefit, paying up to 100% of employees’ monthly transit fares. -

2Special Advertising Section

2 Special Advertising Section shop MERLE HAY MALL GRAND OPENING, SUNDAY, JULY 24 AT 8 AM Soon! The world’s largest and most respected gourmet coff ee company will soon call Merle Hay Mall home! Starbucks, Inc. is currently Just opened! Fun and funky fashion-forward private label constructing an 1,836 square-foot store at the sportswear and accessories for “tweens” ages 7 to 14. east entrance to the mall, across from Applebees. This store will be the fi rst stand-alone store in the Des Moines area. Enjoy tasty beverages, food and merchandise in the comfortable indoor seating area or at the outdoor umbrella tables. In a hurry? Swing through the drive-up window! Opening mid-August. In the Target hallway across from Old Navy shopshop MERLE HAY MALL SpecialSpecial AdvertisingAdvertising Section 3 ISSUE NO. 6: AUGUST/SEPTEMBER/OCTOBER, 2005 Mall Events 4 There’s always something going on at Merle Hay Mall! Look Smart 6 AUGUST 5–31 Get the skinny on the latest fall fashions. Shop Savvy 7 Check out these tips for the back-to-school shopper. Otis’s Fun Forest 8 will be given away to area schools! Ready for a challenge? Try this wordpuzzle! Raising money for your school while you shop at Merle Hay Mall is easy! Here’s how: 1) Shop any store in Merle Hay Mall. VISIT US ONLINE! WWW.MERLEHAYMALL.COM 2) Bring your receipt(s) to Customer Service. All receipts must be from purchases made at Merle Hay Mall from August 5–31, 2005. Each receipt can only be submitted once. -

Track Record of Prior Experience of the Senior Cobalt Team

Track Record of Prior Experience of the Senior Cobalt Team Dedicated Executives PROPERTY City Square Property Type Responsibility Company/Client Term Feet COLORADO Richard Taylor Aurora Mall Aurora, CO 1,250,000 Suburban Mall Property Management - New Development DeBartolo Corp 7 Years CEO Westland Center Denver, CO 850,000 Suburban Mall Property Management and $30 million Disposition May Centers/ Centermark 9 Years North Valley Mall Denver, CO 700,000 Suburban Mall Property Management and Redevelopment First Union 3 Years FLORIDA Tyrone Square Mall St Petersburg, FL 1,180,000 Suburban Mall Property Management DeBartolo Corp 3 Years University Mall Tampa, FL 1,300,000 Suburban Mall Property Management and New Development DeBartolo Corp 2 Years Property Management, Asset Management, New Development Altamonte Mall Orlando, FL 1,200,000 Suburban Mall DeBartolo Corp and O'Connor Group 1 Year and $125 million Disposition Edison Mall Ft Meyers, FL 1,000,000 Suburban Mall Property Management and Redevelopment The O'Connor Group 9 Years Volusia Mall Daytona Beach ,FL 950,000 Suburban Mall Property and Asset Management DeBartolo Corp 1 Year DeSoto Square Mall Bradenton, FL 850,000 Suburban Mall Property Management DeBartolo Corp 1 Year Pinellas Square Mall St Petersburg, FL 800,000 Suburban Mall Property Management and New Development DeBartolo Corp 1 Year EastLake Mall Tampa, FL 850,000 Suburban Mall Property Management and New Development DeBartolo Corp 1 Year INDIANA Lafayette Square Mall Indianapolis, IN 1,100,000 Suburban Mall Property Management -

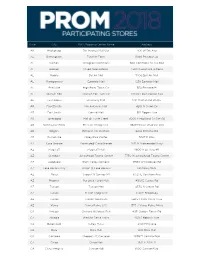

Prom 2018 Event Store List 1.17.18

State City Mall/Shopping Center Name Address AK Anchorage 5th Avenue Mall-Sur 406 W 5th Ave AL Birmingham Tutwiler Farm 5060 Pinnacle Sq AL Dothan Wiregrass Commons 900 Commons Dr Ste 900 AL Hoover Riverchase Galleria 2300 Riverchase Galleria AL Mobile Bel Air Mall 3400 Bell Air Mall AL Montgomery Eastdale Mall 1236 Eastdale Mall AL Prattville High Point Town Ctr 550 Pinnacle Pl AL Spanish Fort Spanish Fort Twn Ctr 22500 Town Center Ave AL Tuscaloosa University Mall 1701 Macfarland Blvd E AR Fayetteville Nw Arkansas Mall 4201 N Shiloh Dr AR Fort Smith Central Mall 5111 Rogers Ave AR Jonesboro Mall @ Turtle Creek 3000 E Highland Dr Ste 516 AR North Little Rock Mc Cain Shopg Cntr 3929 Mccain Blvd Ste 500 AR Rogers Pinnacle Hlls Promde 2202 Bellview Rd AR Russellville Valley Park Center 3057 E Main AZ Casa Grande Promnde@ Casa Grande 1041 N Promenade Pkwy AZ Flagstaff Flagstaff Mall 4600 N Us Hwy 89 AZ Glendale Arrowhead Towne Center 7750 W Arrowhead Towne Center AZ Goodyear Palm Valley Cornerst 13333 W Mcdowell Rd AZ Lake Havasu City Shops @ Lake Havasu 5651 Hwy 95 N AZ Mesa Superst'N Springs Ml 6525 E Southern Ave AZ Phoenix Paradise Valley Mall 4510 E Cactus Rd AZ Tucson Tucson Mall 4530 N Oracle Rd AZ Tucson El Con Shpg Cntr 3501 E Broadway AZ Tucson Tucson Spectrum 5265 S Calle Santa Cruz AZ Yuma Yuma Palms S/C 1375 S Yuma Palms Pkwy CA Antioch Orchard @Slatten Rch 4951 Slatten Ranch Rd CA Arcadia Westfld Santa Anita 400 S Baldwin Ave CA Bakersfield Valley Plaza 2501 Ming Ave CA Brea Brea Mall 400 Brea Mall CA Carlsbad Shoppes At Carlsbad -

State City Shopping Center Address

State City Shopping Center Address AK ANCHORAGE 5TH AVENUE MALL SUR 406 W 5TH AVE AL FULTONDALE PROMENADE FULTONDALE 3363 LOWERY PKWY AL HOOVER RIVERCHASE GALLERIA 2300 RIVERCHASE GALLERIA AL MOBILE BEL AIR MALL 3400 BELL AIR MALL AR FAYETTEVILLE NW ARKANSAS MALL 4201 N SHILOH DR AR FORT SMITH CENTRAL MALL 5111 ROGERS AVE AR JONESBORO MALL @ TURTLE CREEK 3000 E HIGHLAND DR STE 516 AR LITTLE ROCK SHACKLEFORD CROSSING 2600 S SHACKLEFORD RD AR NORTH LITTLE ROCK MC CAIN SHOPG CNTR 3929 MCCAIN BLVD STE 500 AR ROGERS PINNACLE HLLS PROMDE 2202 BELLVIEW RD AZ CHANDLER MILL CROSSING 2180 S GILBERT RD AZ FLAGSTAFF FLAGSTAFF MALL 4600 N US HWY 89 AZ GLENDALE ARROWHEAD TOWNE CTR 7750 W ARROWHEAD TOWNE CENTER AZ GOODYEAR PALM VALLEY CORNERST 13333 W MCDOWELL RD AZ LAKE HAVASU CITY SHOPS @ LAKE HAVASU 5651 HWY 95 N AZ MESA SUPERST'N SPRINGS ML 6525 E SOUTHERN AVE AZ NOGALES MARIPOSA WEST PLAZA 220 W MARIPOSA RD AZ PHOENIX AHWATUKEE FOOTHILLS 5050 E RAY RD AZ PHOENIX CHRISTOWN SPECTRUM 1727 W BETHANY HOME RD AZ PHOENIX PARADISE VALLEY MALL 4510 E CACTUS RD AZ TEMPE TEMPE MARKETPLACE 1900 E RIO SALADO PKWY STE 140 AZ TUCSON EL CON SHPG CNTR 3501 E BROADWAY AZ TUCSON TUCSON MALL 4530 N ORACLE RD AZ TUCSON TUCSON SPECTRUM 5265 S CALLE SANTA CRUZ AZ YUMA YUMA PALMS S C 1375 S YUMA PALMS PKWY CA ANTIOCH ORCHARD @SLATTEN RCH 4951 SLATTEN RANCH RD CA ARCADIA WESTFLD SANTA ANITA 400 S BALDWIN AVE CA BAKERSFIELD VALLEY PLAZA 2501 MING AVE CA BREA BREA MALL 400 BREA MALL CA CARLSBAD PLAZA CAMINO REAL 2555 EL CAMINO REAL CA CARSON SOUTHBAY PAV @CARSON 20700 AVALON -

Marion Meginnis HP 601 December 3, 2014 Term Paper Intent and Outcome: a River Town Retrieves Its Past in 1979, Davenport

Marion Meginnis HP 601 December 3, 2014 Term Paper Intent and Outcome: A River Town Retrieves Its Past In 1979, Davenport began a massive multiple listing effort to nominate properties to the National Register. For Iowa, the effort was unprecedented; it was the first such nomination to be approved by the state and its scope was larger than that of any other Iowa municipality.1 When completed in the 1980’s, more than half of all Iowa National Register properties were located in Davenport.2 In many cities across America, the 1966 passage of the National Historic Preservation Act, the development of state historic preservation offices and enthusiasm for local history surrounding the nation’s Bicentennial celebration triggered local preservation efforts like Davenport’s. Other factors impacting cities and society in the 1970s and 1980s were also in play--a shrinking downtown and move to the suburbs, new voices in the political arena, aggressive transportation planning and dramatic shifts in the area’s economy-- that helped and hindered historic preservation in the old town by the Mississippi. For those whose lives were touched by the effort in Davenport as activists, politicians, business people, journalists, or citizens, what occurred…or is remembered today…varies over the two decades being explored. Davenport is a Mississippi River town platted in 1836 by French/Native American trader Antoine LeClaire. Its geography confuses the unfamiliar since it is sited at one of the few places where the great river flows west. So what would be “west” for most Mississippi River towns is Davenport’s “north.” Any discussion of the city must include a mention of its Iowa and Illinois sister cities. -

Front of Book Blueline.Qxd

THE MACERICH COMPANY Trans formation ANNUAL REPORT 97 MACERICH TRANSFORMS OPPORTUNITIES INTO GROWTH DIVIDEND PAID PER SHARE TOTAL REVENUES IN MILLIONS $1.78 $221.2 $1.66 $1.70 $155.1 $.87 $102.5 $86.0 94 95 96 97 94 95 96 97 The Company has The 37% compounded increased its dividend annual growth rate in each year since becoming total revenue reflects the a public company. Company’s acquisition success. FFO PER SHARE, QUARTERLY $0.61 $0.53 $0.54 $0.48 $0.49 $0.51 $0.47 $0.45 $0.46 $0.42 $0.43 $0.40 $0.41 $0.37 $0.38 $0.34 94 94 94 94 95 95 95 95 96 96 96 96 97 97 97 97 Quarters 1-4 1994 Quarters 1-4 1995 Quarters 1-4 1996 Quarters 1-4 1997 Funds from Operations (FFO) per share have increased for 11 consecutive quarters, tes- timony to the Company’s commitment to per share growth. Great Falls Fargo Billings Rapid City Sioux Falls Sioux City Des Moines Sandy Cedar Rapids Greeley Davenport Boulder Reno Moline Colorado Springs Antioch San Rafael Grand Junction Modesto Walnut Creek Capitola Fresno Oklahoma City Downey Ventura Lakewood Panorama City Santa Ana Marina del Rey Dallas Manhattan Beach Huntington Beach MACERICH PROPERTY LOCATIONS Antioch, California Cedar Rapids, Iowa Des Moines, Iowa Grand Junction, Colorado County East Mall Lindale Mall SouthRidge Mall Mesa Mall 488,883 square feet 691,940 square feet 993,875 square feet 851,354 square feet Billings, Montana Clarksville, Indiana Downey, California Great Falls, Montana Rimrock Mall Green Tree Mall Stonewood Mall Great Falls Marketplace 581,688 square feet 782,687 square feet 927,218 -

Dsmpartnership.Com Edwards Park City Park KNOXVILLE

1 44 Woodward 1 44 Golf Club PERRY 1 41 Perry Municipal WOODWARD To Ames 330 Airport Big North To Marshalltown BAXTER Creek Northeast 29 Miles 223 Lake 28 Miles ALLEMAN 65 169 17 ELKHART Chichaqua Jester Park Tournament Wildlife Club of Iowa Habitat Park POLK GRANGER Jester Park Golf Course CITY Briarwood Otter Creek Golf Course Golf Course MINGO MINBURN MileLong Bridge 41 5 35 Faith Baptist Polk County Bible College and Theological Seminary Beaver Creek Golf Club ANKENY VALERIA Public Course Ankeny Saylorville Golf and Country Club 69 Lake 69 117 BONDURANT 160 Hyperion 80 LAMBS GROVE Field Club Ankeny 80 Cottonwood Westwood Regional Camp Dodge Recreation Golf Course 44 Airport 44 Area Woodland Hills DALLAS CENTER GRIMES JOHNSTON Golf Course NEWTON Margo Frankel 65 COLFAX Woods State Park MITCHELLVILLE Jasper County To Grinnell East 30 Miles River Valley Golf Course 65 Terrace Hills 35 80 Golf Course Dallas Co unty 80 Thomas RR ALTOONA Mitchell VA C entral Hillcrest County Park Country Club URBANDALE Iowa Health 6 Merle Hay Mall Care System 6 Broadlawns Urbandale 6 Grand View Medical Golf and University Center Bright 169 ITT TechnicalCountry Club 235 Institute - Grandview Copper Creek Golf 6 Golf Course Club and Clive Mercy Iowa Lutheran Mercy Medical Events Center CLI VE Greenbelt Waveland Drake Medical Hospital ADEL Sugar Creek Des Moines Center - Park WINDSOR Golf Course University WAU KEE West Lakes Center Golf Course Golf HEIGHTS 6 and Country Club Valley West Mall Methodist Toad Valley University of PRAIRIE CITY West Hospital Iowa -

Store # State City Mall/Shopping Center Name Address Date 2918

Store # State City Mall/Shopping Center Name Address Date 2918 AL ALABASTER COLONIAL PROMENADE 340 S COLONIAL DR Coming Soon in September 2016! 2218 AL HOOVER RIVERCHASE GALLERIA 2300 RIVERCHASE GALLERIA Coming Soon in September 2016! 2131 AL HUNTSVILLE MADISON SQUARE 5901 UNIVERSITY DR Coming Soon in September 2016! 219 AL MOBILE BEL AIR MALL MOBILE, AL 36606-3411 Coming Soon in September 2016! 2840 AL MONTGOMERY EASTDALE MALL MONTGOMERY, AL 36117-2154 Coming Soon in September 2016! 2956 AL PRATTVILLE HIGH POINT TOWN CENTER PRATTVILLE, AL 36066-6542 Coming Soon in September 2016! 2875 AL SPANISH FORT SPANISH FORT TOWN CENTER 22500 TOWN CENTER AVE Coming Soon in September 2016! 2869 AL TRUSSVILLE TUTWILER FARM 5060 PINNACLE SQ Coming Soon in September 2016! 2709 AR FAYETTEVILLE NW ARKANSAS MALL 4201 N SHILOH DR Coming Soon in September 2016! 1961 AR FORT SMITH CENTRAL MALL 5111 ROGERS AVE Coming Soon in September 2016! 2914 AR LITTLE ROCK SHACKLEFORD CROSSING 2600 S SHACKLEFORD RD Coming Soon in July 2016! 663 AR NORTH LITTLE ROCK MC CAIN SHOPPING CENTER 3929 MCCAIN BLVD STE 500 Coming Soon in July 2016! 2879 AR ROGERS PINNACLE HLLS PROMDE 2202 BELLVIEW RD Coming Soon in September 2016! 2936 AZ CASA GRANDE PROMNDE AT CASA GRANDE 1041 N PROMENADE PKWY Coming Soon in September 2016! 157 AZ CHANDLER MILL CROSSING 2180 S GILBERT RD Coming Soon in September 2016! 251 AZ GLENDALE ARROWHEAD TOWNE CENTER 7750 W ARROWHEAD TOWNE CENTER Coming Soon in September 2016! 2842 AZ GOODYEAR PALM VALLEY CORNERST 13333 W MCDOWELL RD Coming Soon in September -

Store # Phone Number Store Shopping Center/Mall Address City ST Zip District Number 318 (907) 522-1254 Gamestop Dimond Center 80

Store # Phone Number Store Shopping Center/Mall Address City ST Zip District Number 318 (907) 522-1254 GameStop Dimond Center 800 East Dimond Boulevard #3-118 Anchorage AK 99515 665 1703 (907) 272-7341 GameStop Anchorage 5th Ave. Mall 320 W. 5th Ave, Suite 172 Anchorage AK 99501 665 6139 (907) 332-0000 GameStop Tikahtnu Commons 11118 N. Muldoon Rd. ste. 165 Anchorage AK 99504 665 6803 (907) 868-1688 GameStop Elmendorf AFB 5800 Westover Dr. Elmendorf AK 99506 75 1833 (907) 474-4550 GameStop Bentley Mall 32 College Rd. Fairbanks AK 99701 665 3219 (907) 456-5700 GameStop & Movies, Too Fairbanks Center 419 Merhar Avenue Suite A Fairbanks AK 99701 665 6140 (907) 357-5775 GameStop Cottonwood Creek Place 1867 E. George Parks Hwy Wasilla AK 99654 665 5601 (205) 621-3131 GameStop Colonial Promenade Alabaster 300 Colonial Prom Pkwy, #3100 Alabaster AL 35007 701 3915 (256) 233-3167 GameStop French Farm Pavillions 229 French Farm Blvd. Unit M Athens AL 35611 705 2989 (256) 538-2397 GameStop Attalia Plaza 977 Gilbert Ferry Rd. SE Attalla AL 35954 705 4115 (334) 887-0333 GameStop Colonial University Village 1627-28a Opelika Rd Auburn AL 36830 707 3917 (205) 425-4985 GameStop Colonial Promenade Tannehill 4933 Promenade Parkway, Suite 147 Bessemer AL 35022 701 1595 (205) 661-6010 GameStop Trussville S/C 5964 Chalkville Mountain Rd Birmingham AL 35235 700 3431 (205) 836-4717 GameStop Roebuck Center 9256 Parkway East, Suite C Birmingham AL 35206 700 3534 (205) 788-4035 GameStop & Movies, Too Five Pointes West S/C 2239 Bessemer Rd., Suite 14 Birmingham AL 35208 700 3693 (205) 957-2600 GameStop The Shops at Eastwood 1632 Montclair Blvd. -

THE MACERICH COMPANY (Exact Name of Registrant As Specified in Charter)

UNITED STATES SECURITIES AND EXCHANGE COMMISSION WASHINGTON, DC 20549 FORM 8-K CURRENT REPORT Pursuant to Section 13 or 15(d) of the Securities Exchange Act of 1934 Date of report (Date of earliest event reported) May 12, 2020 THE MACERICH COMPANY (Exact Name of Registrant as Specified in Charter) MARYLAND 1-12504 95-4448705 (State or Other Jurisdiction (Commission (IRS Employer of Incorporation) File Number) Identification No.) 401 Wilshire Boulevard, Suite 700, Santa Monica, California 90401 (Address of Principal Executive Offices) (Zip Code) Registrant’s telephone number, including area code (310) 394-6000 N/A (Former Name or Former Address, if Changed Since Last report) Check the appropriate box below if the Form 8-K filing is intended to simultaneously satisfy the filing obligation of the registrant under any of the following provisions (see General Instruction A.2. below): ☐ Written communications pursuant to Rule 425 under the Securities Act (17 CFR 230.425) ☐ Soliciting material pursuant to Rule 14a-12 under the Exchange Act (17 CFR 240.14a-12) ☐ Pre-commencement communications pursuant to Rule 14d-2(b) under the Exchange Act (17 CFR 240.14d-2(b)) ☐ Pre-commencement communications pursuant to Rule 13e-4(c) under the Exchange Act (17 CFR 240.13e-4(c)) Securities registered pursuant to Section 12(b) of the Act: Name of each exchange Title of each class Trading symbol(s) on which registered Common stock of The Macerich Company, MAC The New York Stock Exchange $0.01 par value per share Indicate by check mark whether the registrant is an emerging growth company as defined in Rule 405 of the Securities Act of 1933 (17 CFR §230.405) or Rule 12b-2 of the Securities Exchange Act of 1934 (17 CFR §240.12b-2). -

GGP Evolving 2007 Annual Report

ORT P 7 ANNUAL RE 7 ANNUAL 200 GENERAL GROWTH PROPERTIES | 2007 ANNUAL REPORT ggp.com | 960-5000 ) 312 110 North Wacker Drive, Chicago, Illinois 60606 North Wacker 110 ( ggp | evolving The people of General Growth Properties create and operate some of the most exciting, vibrant and entertaining shopping centers and planned communities in the world. But our passion is to think bigger —beyond the structures and lift | company profi le property we own—to the environment we share lift | fi nancial highlights and the communities we serve. In that spirit, GGP 1 | shareholders’ letter continuously fi nds situations where sustainability is 17 | retail portfolio as good for our business as it is for the environment. following portfolio | form 10-K Staying true to our vision and values, using honest directors/offi cers evaluations and the powerful multiplier of teamwork, corporate information GGP strives to evolve every area of our business. Bridgeland Houston, Texas company profi le General Growth Properties, Inc. is one of the largest U.S.- based publicly traded real estate investment trusts (REIT) based upon market capitalization. Best known for its ownership or management of more than 200 shopping malls in 45 states, we are also a leading developer of master planned communities and mixed-use properties. We have ownership interests in master planned communities in Texas, Maryland and Nevada and in smaller mixed-use projects under development in additional locations. Our shopping center portfolio totals FINANCIAL HIGHLIGHTS dollars in thousands, except per share amounts approximately 200 million square feet of retail space accommodating more than % Change 2007 24,000 retail stores nationwide.