Language and Culture 2Nd, April,2020

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Imam Sibawaihi Dan Karya Utamanya, Al-Kit.I/J. Tinjauan

MUFTIALI, S. Ag,MA Imam Sibawaihidan KaryaUtamanya, al-Kit.i/J. Tinjauan Bibliografis*> Abstrak Sebagai seorang sarjana yang dianggap telah memperkenalkan pendekatan baru pada studi bahasa, di mana pemikiran gramatikalnya dijuluki sebagai titik berangkat (starting point) sejarah tata bahasa Arab, Sibawayhi menclapatkan perhatian cukup luas dari para 8:hllbahasa dan sejarah bahasa Arab khususnya dan dari para ahli sejarah literatur Islam umumnya, baik di Barat maupun di Timur. Secara garis besar perhatian para ahli tersebut berkisar mengenai biografi, kontribusi pemikiran gramatikal Sibawayhi kepada tata bahasa Arab, reaksi para ahli · nahwu generasi pertama pada pemikiran Sibawayhi, posisi pemikiran gramatikal Sibawayhi di tengah mazhab grammar yang berkembang saat itu, masterpiece Sibawayh, al-Kitdb, manuskrip dan orisinalitas pemikirannya. Dalam karya tulis ini didiskusikan secara sekilas biografi dan karya utama Sibawayhi (al-Kitab). Diskusi mengeilai biografi Sibawayhi meliputi diskusi hubungan guru-murid Sibawayhi dengan sejumlah ahli gramatikal; sementara diskusi mengenai karya utamanya meliputi: Pertama, ruang lingkup al-Kitab; kedua, manuskrip, publikasi, dan translasi karya tersebut; ketiga, al-Kitab dalam konteks persaingan antara faksi Kufah dan Basrah; keempat, orisinalitas pemikiran Sibawayhi dalam al-Kitdb; dan kelima, pengaruh pemikiran gramatikal Sibawayhi terhadap pemikiran· 1 Makalah ini disampaikan pada diskusi dosen-dosen pada Pusat Kajian islam dan Kemasyarakatan (PKIK) STAIN 'Sultan Maulana Hasanuddin Banten' Serang Banten tanggal 17 April 2001. Penulis sangat berterima kasih atas saran dan kritik dari teman- . · teman dosen STAIN 'SMHB' Serang. I gramatikal ahli gramatika setelahnya. Pada bagian akhir tulisan ini dicantumkan daftar bibliografi yang mendiskusikan biografi dan seluruh aspek pemikiran gramatikal Sibawayhi yang disusun secara kronologis. Key Words: Sibawayhi, Biography, al-Kitab A. -

Mmubn000001 083965866.Pdf

PDF hosted at the Radboud Repository of the Radboud University Nijmegen The following full text is a publisher's version. For additional information about this publication click this link. http://hdl.handle.net/2066/148538 Please be advised that this information was generated on 2021-09-29 and may be subject to change. 2\ ΙЧ GREEK ELEMENTS IN ARABIC LINGUISTIC THINKING PROEFSCHRIFT TER VERKRIJGING VAN DE GRAAD VAN DOCTOR IN DE LETTEREN AAN DE KATHOLIEKE UNIVERSITEIT TE NIJMEGEN, OP GEZAG VAN DE RECTOR MAGNIFICUS PROF DR. A.J.H. VENDRIK VOLGENS BESLUIT VAN HET COLLEGE VAN DEKANEN IN HET OPENBAAR TE VERDEDIGEN OP 13 JANUARI 1977 TE 16.00 UUR DOOR CORNELIS HENRICUS MARIA VERSTEEGH geboren op 17 oktober 1947 te Arnhem LEIDEN E.J. BRILL 1977 GREEK ELEMENTS IN ARABIC LINGUISTIC THINKING GREEK ELEMENTS IN ARABIC LINGUISTIC THINKING PROEFSCHRIFT TER VERKRIJGING VAN DE GRAAD VAN DOCTOR IN DE LETTEREN AAN DE KATHOLIEKE UNIVERSITEIT TE NIJMEGEN, OP GEZAG VAN DE RECTOR MAGNIFICUS PROF DR A J H VENDR1K VOLGENS BESLUIT VAN HET COLLEGE VAN DEKANEN IN HET OPENBAAR TE VERDEDIGEN OP 13 JANUARI 1977 TE 16 00 UUR DOOR CORNELIS HENRICUS MARIA VERSTEEGH geboren op 17 oktober 1947 te Arnhem LEIDEN E.J. BRILL 1977 The publication of this book was made possible through a grant from the Netherlands organization for the Advancement of Pure Research (Z.W.O.) Promotor : Prof. Dr. S. WILD Co-promotor : Prof. Dr. M. VAN STRAATEN OSA TABLE OF CONTENTS Preface . I. The first contact with Greek grammar . II. Articulated sound and its meaning III. -

Disciples of Hadith: the Noble Guardians – Al-Khatib Al-Baghdadi

| \ Cia N nd | ‘En a Ne ODE HAP sa TYSex Suse we va — 6 Yh, Bm LO) ay) z al-Hafiz Aba Bakr Ahmad Ibn ‘Ali al-Khatib al-Baghdadi (d.463H) of Hadith Disciplesbeing a translation of his Sharaf al-Ashab al-Hadith wa Nasibatu Ablu’l-Hadith | The Messenger of Allah (3%) said: ““May Allah cause a slave to flourish who heard my words and understands them, then he conveys them from me. There may be those who have knowledge but no understanding, and there may be those who convey knowledge to those who may 399 have more understanding of it than they do. [Aba Dawid #3660 and Tirmidhi #2656] Disciples of Hadith The Noble Guardians With accompanying notes of the author advisingAblu’lHadith by al-Hafiz Abt Bakr Ahmad Ibn ‘Ali al-Khatib al-Baghdadi (d. 463 H) Dar as-Sunnah Publishers BIRMINGHAM First Published in Great Britain June 2020 / Dhu’l-Qa‘dah 1441H by Dar as-Sunnah Publishers DAR AS-SUNNAH PUBLISHERS P.O. Box 9818, Birmingham, B11 4WA, United Kingdom W: www.darassunnah.com E:; [email protected] E: [email protected] © Copyright 2020 by Dar as-Sunnah Publishers All rights reserved Worldwide. No part of this publication may be reproduced including the cover design, utilized or transformed in any form or means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopy, recording of any information storage and retrieval system, now known or to be invented without the express permission in writing from the publisher, nor be otherwise circulated in any form of binding or cover other then that in which it is published and without a similar condition being imposed on the subsequent purchaser. -

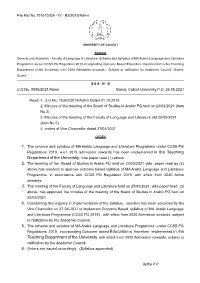

In the Teaching Department of the University, Vide Paper Read (1) Above

File Ref.No.101610/GA - IV - B2/2019/Admn UNIVERSITY OF CALICUT Abstract General and Academic - Faculty of Language & Literature- Scheme and Syllabus of MA Arabic Language and Literature Programme as per CCSS PG Regulation 2019 incorporating Outcome Based Education- Implemented in the Teaching Department of the University w.e.f 2020 Admission onwards - Subject to ratification by Academic Council -Orders Issued. G & A - IV - B U.O.No. 5598/2021/Admn Dated, Calicut University.P.O, 26.05.2021 Read:-1. U.O.No. 15363/2019/Admn Dated 31.10.2019 2. Minutes of the meeting of the Board of Studies in Arabic PG held on 23/02/2021 (Item No 2) 3. Minutes of the meeting of the Faculty of Language and Literature dtd 25/03/2021 (item No 5) 4. orders of Vice Chancellor dated 27/04/2021 ORDER 1. The scheme and syllabus of MA Arabic Language and Literature Programme under CCSS PG Regulations 2019, w.e.f 2019 admission onwards has been implemented in the Teaching Department of the University, vide paper read (1) above. 2. The meeting of the Board of Studies in Arabic PG held on 23/02/2021 vide paper read as (2) above has resolved to approve outcome based syllabus of MA Arabic Language and Literature Programme, in accordance with CCSS PG Regulation 2019, with effect from 2020 Admn onwards. 3. The meeting of the Faculty of Language and Literature held on 25/03/2021, vide paper read (3) above, has approved the minutes of the meeting of the Board of Studies in Arabic PG held on 23/02/2021. -

TABARKANE Tayeb-Zum Beitrag Der Araber Zur Geschichte Und

Zum Beitrag der Araber zur Geschichte und Entwicklung der Sprachwissenschaft TABARKANE Tayeb Laboratoire Traduction et Méthodologie (TRADTEC) Université d’Oran 2 Zusammenfassung In diesem Artikel unter dem Titel „ Zum Beitrag der Araber zur Geschichte und Entwicklung der Sprachwissenschaft“ handelt es sich vor allem um die Positive Rolle bzw. den Beitrag der Araber bei der Entwicklung der Sprachwissenschaft. Die historische Bedeutung der arabischen Sprache im Mittelalter, das in Europa auch als das „finstere“ Zeitalter gilt, haben arabische Sprachwissenschaftler für ihre Sprache getan, was kein anderes Volk der Erde aufzuweisen vermag. Es gab auch Gelehrte und Historiker viele Werke der Antike aus dem Griechischen ins Arabische übersetzt. Schlüsselwörter: Die arabische Sprache, Geschichte der Sprachwissenschaft, Mittelalter. Abstract: The historical importance of the Arabic language in the Middle Ages, which in Europe is also considered the „dark“ age, has been done by Arabic linguists for their language, which no other people on earth can show. There were also scholars and historians translated many works of antiquity from Greek into Arabic. This article, titled „The Contribution of Arabs to the History and Development of Linguistics“, focuses on the positive role and contribution of Arabs in the development of linguistics. The aim of this article is not only to tell and rewrite the whole history of Arabic linguistics, but also to treat the Arabs‘ knowledgeable aspects of the history and development of linguistics. To know what the Arabs added to linguistics. Keywords: The Arabic language, history of linguistics, middle Ages. 1. Einführung Die arabische Sprache ist eine semitische Sprache und eine der sechs offiziellen Sprachen der vereinten Nationen wie Englisch, Französisch, Spanisch, Russisch und Chinesisch. -

Ah and Islamic Disciplines

Published on Books on Islam and Muslims | Al-Islam.org (http://www.al-islam.org) Home > The Shi'ah and Islamic Disciplines The Shi'ah and Islamic Disciplines Log in [1] or register [2] to post comments The writer is an erudite scholar who, with authority discusses the Islamic and Arabic sciences, the factors responsible for their emergence and the various stages of their development throughout Shi'a sources.. Author(s): ● Sayyid Hasan al-Sadr [3] Translator(s): ● 'Umar Kumo [4] Publisher(s): ● ABWA Publishing and Printing Center [5] Category: ● General [6] ● General [7] ● Scholars [8] Topic Tags: ● Islamic Sciences [9] Miscellaneous information: The Shi'ah and Islamic Disciplines Author: Sayyid Hasan al–Sadr Translator: 'Umar Kumo Project supervisor: Translation Unit, Cultural Affairs Department / The Ahl al–Bayt (‘a) World Assembly (ABWA) Editor: Sayyid 'Abbas Husseini Publisher: ABWA Publishing and Printing Center First Printing: 2007 Printed by: Layla Press Copies: 5, 000 © Ahl al–Bayt (‘a) World Assembly (ABWA) www. ahl–ul–bayt. org info@ahl–ul–bayt. org ISBN: 978-964–529–554–5 ﻓﻨﻮن اﻻﺳﻼم ﻧﻮﻳﺴﻨﺪه: ﺳﯿﺪ ﺣﺴﻦ اﻟﺼﺪر ﻣﺘﺮﺟﻢ: ﻋﻤﺮ ﮐﻮﻣﻮ زﺑﺎن ﻧﺎم ﻛﺘﺎب: اﻟﺸﯿﻌﻪ و All rights reserved ﺗﺮﺟﻤﻪ: اﻧﮕﻠﻴﺴﻰ Featured Category: ● Resources for Further Research [10] ● Shi'a beliefs explained [11] Preface In the Name of Allah, the All–beneficent, the All–merciful The invaluable legacy of the Household [Ahl al-Bayt] of the Prophet (may peace be upon them all), as preserved by their followers, is a comprehensive school of thought that embraces all branches of Islamic knowledge. This school has produced many brilliant scholars who have drawn inspiration from this rich and pure resource. -

Glimpses of Nahjul-Balagha

Glimpses of Nahjul-Balagha Author(s): Murtadha Mutahhari [1] Publisher(s): Tahrike-Tarsile-Qur’an [2] This book is divided into seven parts. The introduction analyses the literary excellence and multi- dimensionality of Nahjul-Balagha, quoting various viewpoints expressed about Imam Ali’s eloquence in general and as expressed in the book in particular. The other parts analyse the Nahjul-Balaghah in themes: theology and metaphysics, ibadah and its various levels, justice and righteous government, khilafah, morality, and spirituality. It also covers ethical teachings, in particular the Islamic concept of zuhd (asceticism), and the meaning of the contrast between life in this world and that in the hereafter. Get PDF [3] Get EPUB [4] Get MOBI [5] Translator(s): Ali Quli Qara'i [6] Topic Tags: Nahj al-Balagha [7] Person Tags: Imam Ali [8] Part One In the Name of Allah, the most Gracious, the most Merciful The book consists of several parts. In the first, he discusses the two main characteristics of Nahjul- Balagha, its literary excellence and multi-dimensionality, quoting various viewpoints expressed about Imam Ali’s eloquence in general and Nahjul-Balagha in particular. In the second part, the author discusses the theological and metaphysical ideas embedded in Nahjul-Balagha, comparing them with parallel viewpoints with which Muslim orators and philosophers are familiar. The third part deals with ibada (adoration) and its various levels. The fourth part deals with the Islamic Government and Social Justice. The fifth, which deals with the controversial issue of caliphate (khilafa) and the superior status of Ahl al-Bayt (as), is deleted from this translation. -

Review Obligations in the Works Talae Ben Rzyk

Nature and Science 2016;14(10) http://www.sciencepub.net/nature Review obligations in the works talae Ben Rzyk Saeed Albo kord Department of Arabic Language and literature, Abadan Branch, Islamic Azad university, Abadan, Iran Abstract: Concept of God in the Qur'an and prophetic traditions of their art text-Shiite poets have long been the focus of attention. It should be noted that all translations made by the poet in this work is done by the author. [Saeed Albo kord. Review obligations in the works talae Ben Rzyk. Nat Sci 2016;14(10):15-19]. ISSN 1545-0740 (print); ISSN 2375-7167 (online). http://www.sciencepub.net/nature. 3. doi:10.7537/marsnsj141016.03. Key words: talae Ben Rzyk, commitment, Quran, intertextuality and the Holy Quran. Introduction Field of study It is an imperative for any text and any literary Scientific research has been published in addition text, this is no exception. Cash new trends such as to the documentation of databases and internet sites. intertextuality, Bsyarnaqdan attention to the works of Definitions of important words and phrases ancient poets and literary tradition and the freshness Talae Ben Rzyk and prosperity Sarjdyd added. Abvalgharat, Muslim Nasir al-Din al-Mulk al- Masrrb literature, the concept of intertextual it as Fares, talae Ben Rzyk bin Saleh was born in the year "Tnas" will be remembered, the cash impact of 495 AH Drkhanvad of religion and the world that God research through cultural relations of the West, which had given to them. After her father in the upbringing has been highly regarded. -

Glimpses of the Nahj Al-Balaghah

Part 1 INTRODUCTION: 2 This is the first part of Martyr Mutahhari's book Sayri dar Nahj al-bal- aghah, and consists of the introduction and the first section of the book. The introduction, which the author, presumably wrote before giving the book to the publishers is dated Muharram 3, 1995 (January 15, 1975). INTRODUCTION: Perhaps it may have happened to you, and if not, you may still visual- ize it: someone lives on your street or in your neighbourhood for years; you see him at least once every day and habitually nod to him and pass by. Years pass in this manner, until, one day, accidentally, you get an op- portunity to sit down with him and to become familiar with his ideas, views and feelings, his likes and dislikes. You are amazed at what you have come to know about him. You never imagined or guessed that he might be as you found him, and never thought that he was what you later discovered him to be. After that, whenever you see him, his face, somehow, appears to be dif- ferent. Not only this, your entire attitude towards him is altered. His per- sonality assumes a new meaning, a new depth and respect in your heart, as if he were some person other than the one you thought you knew for years. You feel as if you have discovered a new world. My experience was similar in regard to the Nahj al-balaghah. From my childhood years I was familiar with the name of this book, and I could distinguish it from other books on the shelves in my father's library.