Interview Transcript As

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Remembering Operation Jaywick : Singapore's Asymmetric Warfare

This document is downloaded from DR‑NTU (https://dr.ntu.edu.sg) Nanyang Technological University, Singapore. Remembering Operation Jaywick : Singapore’s Asymmetric Warfare Kwok, John; Li, Ian Huiyuan 2018 Kwok, J. & Li, I. H. (2018). Remembering Operation Jaywick : Singapore’s Asymmetric Warfare. (RSIS Commentaries, No. 185). RSIS Commentaries. Singapore: Nanyang Technological University. https://hdl.handle.net/10356/82280 Nanyang Technological University Downloaded on 24 Sep 2021 04:43:21 SGT Remembering Operation Jaywick: Singapore’s Asymmetric Warfare By John Kwok and Ian Li Synopsis Decades before the concept of asymmetric warfare became popular, Singapore was already the site of a deadly Allied commando attack on Japanese assets. There are lessons to be learned from this episode. Commentary 26 SEPTEMBER 2018 marks the 75th anniversary of Operation Jaywick, a daring Allied commando raid to destroy Japanese ships anchored in Singapore harbour during the Second World War. Though it was only a small military operation that came under the larger Allied war effort in the Pacific, it is worth noting that the methods employed bear many similarities to what is today known as asymmetric warfare. States and militaries often have to contend with asymmetric warfare either as part of a larger campaign or when defending against adversaries. Traditionally regarded as the strategy of the weak, it enables a weaker armed force to compensate for disparities in conventional force capabilities. Increasingly, it has been employed by non-state actors such as terrorist groups and insurgencies against the United States and its allies to great effect, as witnessed in Iraq, Afghanistan, and more recently Marawi. -

PDF for Download

THE AUSTRALIAN WAR MEMORIAL National Collection Development Plan The Australian War Memorial commemorates the sacrifice of Australian servicemen and servicewomen who have died in war. Its mission is to help Australians to remember, interpret and understand the Australian experience of war and its enduring impact on Australian society. The Memorial was conceived as a shrine, museum and archive that supports commemoration through understanding. Its development through the years has remained consistent with this concept. Today the Memorial is a commemorative centrepiece; a museum, housing world-class exhibitions and a diverse collection of material relating to the Australian experience of war; and an archive holding extensive official and unofficial documents, diaries and papers, making the Memorial a centre of research for Australian military history. The Australian War Records Section Trophy Store at Peronne. AWM E03684 The National Collection The Australian War Memorial houses one of Australia’s most significant museum collections. Consisting of historical material relating to Australian military history, the National Collection is one of the most important means by which the Memorial presents the stories of Australians who served in war. The National Collection is used to support exhibitions in the permanent galleries, temporary and travelling exhibitions, education and public programs, and the Memorial’s website. Today, over four million items record the details of Australia’s involvement in military conflicts from colonial times to the present day. Donating to the National Collection The National Collection is developed largely by donations received from serving or former members of Australia’s military forces and their families. These items come to the Memorial as direct donations or bequests, or as donations under the Cultural Gifts program. -

The Allied Intelligence Bureau

APPENDIX 4 THE ALLIED INTELLIGENCE BUREAU Throughout the last three volumes of this series glimpses have bee n given of the Intelligence and guerilla operations of the various organisa- tions that were directed by the Allied Intelligence Bureau . The story of these groups is complex and their activities were diverse and so widesprea d that some of them are on only the margins of Australian military history . They involved British, Australian, American, Dutch and Asian personnel , and officers and men of at least ten individual services . At one time o r another A.I.B. controlled or coordinated eight separate organisations. The initial effort to establish a field Intelligence organisation in what eventually became the South-West Pacific Area was made by the Aus- tralian Navy which, when Japan attacked, had a network of coastwatche r stations throughout the New Guinea territories . These were manned by people living in the Australian islands and the British Sololnons . The development and the work of the coastwatchers is described in some detai l in the naval series of this history and in The Coast Watchers (1946) by Commander Feldt, who directed their operations. The expulsion of Allied forces from Malaya, the Indies and the Philip- pines, and also the necessity of establishing Intelligence agencies withi n the area that the enemy had conquered brought to Australia a numbe r of Allied Intelligence staffs and also many individuals with intimate know - ledge of parts of the territories the Japanese now occupied . At the summit were, initially, the Directors of Intelligence of the thre e Australian Services . -

Special Unit Force

HERITAGE SERVICES INFORMATION SHEET NUMBER 14 THE KRAIT AND “Z” SPECIAL UNIT FORCE Did you know that as a dress rehearsal for the Krait’s first attack on Singapore harbour during World War II, the Scorpion party raided shipping anchored in Townsville harbour? Commandos from “Z” Special Force Unit, attached mock up limpet mines to ships in the Cleveland Bay and the Australian War Memorial Negative Number harbour and demonstrated the city’s PO1806.008. Photograph showing lack of maritime security during members of “Z” Force training in canoes on the Hawkesbury River. wartime. The Scorpion Raid Sam Carey was given information that the At 11 pm on 19 June 1943 the train from Black River was tidal and that his party Cairns stopped just before the Black River would have no difficulty paddling down it to bridge. 10 soldiers laden with gear the sea. He was shocked when he jumped from the last carriage of the train. discovered that the river was a series of Their mission was to launch a mock raid waterholes separated by stretches of on ships in Townsville harbour to test their sand. This meant the men had to carry ability to undertake a similar mission and drag the boats between the aimed at Japanese shipping. Naval waterholes. It was not until late on the 20 authorities in Townsville were unaware June that they reached the mouth of the that the raid would take place as the group Black River and the shores of Halifax Bay. needed to obtain a true indicator of their The men were tired and exhausted by this preparedness. -

Life Stories of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Servicemen and Women / Noah Riseman

IN DEFENCE OF COUNTRY Life Stories of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Servicemen & Women Aboriginal History Incorporated Aboriginal History Inc. is a part of the Australian Centre for Indigenous History, Research School of Social Sciences, The Australian National University, and gratefully acknowledges the support of the School of History and the National Centre for Indigenous Studies, The Australian National University. Aboriginal History Inc. is administered by an Editorial Board which is responsible for all unsigned material. Views and opinions expressed by the author are not necessarily shared by Board members. Contacting Aboriginal History All correspondence should be addressed to the Editors, Aboriginal History Inc., ACIH, School of History, RSSS, 9 Fellows Road (Coombs Building), Acton, ANU, 2601, or [email protected]. WARNING: Readers are notified that this publication may contain names or images of deceased persons. IN DEFENCE OF COUNTRY Life Stories of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Servicemen & Women NOAH RISEMAN Published by ANU Press and Aboriginal History Inc. The Australian National University Acton ACT 2601, Australia Email: [email protected] This title is also available online at press.anu.edu.au National Library of Australia Cataloguing-in-Publication entry Creator: Riseman, Noah, 1982- author. Title: In defence of country : life stories of Aboriginal and Torres Strait islander servicemen and women / Noah Riseman. ISBN: 9781925022780 (paperback) 9781925022803 (ebook) Series: Aboriginal history monograph. Subjects: Aboriginal Australians--Wars--Veterans. Aboriginal Australian soldiers--Biography. Australia--Armed Forces--Aboriginal Australians. Dewey Number: 355.00899915094 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying or otherwise, without the prior permission of the publisher. -

COASTWATCHERS: NO MORE SMELLING FLOWERS by Ken Wright

COASTWATCHERS: NO MORE SMELLING FLOWERS By Ken Wright People over impressed by spies and espionage are fond of quoting the observation attributed to the Napoleon Bonaparte when he estimated that a spy in the right place was worth twenty thousand troops. Perhaps he didn’t pay his spies enough as he won the Battle of Wagram then lost the battle of Waterloo, lost his attempt to take Moscow, lost his position as Emperor of France and was finally exiled to the island of Elba. However, his observation about the worth of spies was certainly correct when applied to the Coastwatching organisation in the Pacific during World War II. The original Australian model began in 1919 when selected personnel in coastal areas were organised on a voluntary basis to report in time of war any unusual or suspicious events along the Australian coastline. The concept was quickly extended to include Australian New Guinea as well as Papua and the Solomon Islands. In 1939 when World War II commenced, approximately 800 Coastwatchers came under the control of the Royal Australian Navy Intelligence Division. Lieutenant Commander Eric Feldt had operational control of the Coastwatchers in the north-eastern area of defence which encompassed Australian Mandated New Guinea, Papua, the Solomon Islands and Australia. Eric Feldt was previously a navy man but resigned to work for the Australian government in New Guinea. He grew to know and understand the island people, plantation managers and assorted government officials and they in turn came to know and trust him. Because of their trust in Feldt, when the war with Japan began many civilians opted to stay in New Guinea rather than be evacuated as the Japanese war machine advanced through the Pacific. -

IN DEFENCE of COUNTRY Life Stories of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Servicemen & Women Aboriginal History Incorporated Aboriginal History Inc

IN DEFENCE OF COUNTRY Life Stories of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Servicemen & Women Aboriginal History Incorporated Aboriginal History Inc. is a part of the Australian Centre for Indigenous History, Research School of Social Sciences, The Australian National University, and gratefully acknowledges the support of the School of History and the National Centre for Indigenous Studies, The Australian National University. Aboriginal History Inc. is administered by an Editorial Board which is responsible for all unsigned material. Views and opinions expressed by the author are not necessarily shared by Board members. Contacting Aboriginal History All correspondence should be addressed to the Editors, Aboriginal History Inc., ACIH, School of History, RSSS, 9 Fellows Road (Coombs Building), Acton, ANU, 2601, or [email protected]. WARNING: Readers are notified that this publication may contain names or images of deceased persons. IN DEFENCE OF COUNTRY Life Stories of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Servicemen & Women NOAH RISEMAN Published by ANU Press and Aboriginal History Inc. The Australian National University Acton ACT 2601, Australia Email: [email protected] This title is also available online at press.anu.edu.au National Library of Australia Cataloguing-in-Publication entry Creator: Riseman, Noah, 1982- author. Title: In defence of country : life stories of Aboriginal and Torres Strait islander servicemen and women / Noah Riseman. ISBN: 9781925022780 (paperback) 9781925022803 (ebook) Series: Aboriginal history monograph. Subjects: Aboriginal Australians--Wars--Veterans. Aboriginal Australian soldiers--Biography. Australia--Armed Forces--Aboriginal Australians. Dewey Number: 355.00899915094 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying or otherwise, without the prior permission of the publisher. -

Soldier on a Secret Mission

SOLDIER ON A SECRET MISSION Gordon Senior Carter was a pupil at Mount Albert Grammar School from 1924-1927. He did well at School, in both 3rd and 4th Forms [Years 9 and 10]. He got High Merits Certificates in Latin, French and Drawing, and in 1925 he got a Credit for English. Two more Credits came in both 5A and 6B. He next appears as a surveyor and road engineer in Sarawak. Borneo, where he worked for Shell Oil. During World War II he evaded capture by the invading Japanese forces in 1941 and joined the Royal Australian Engineers in 1942 and saw service in New Guinea. He then joined the secretive Z Special Unit and with seven others he was parachuted into an area of Sarawak likely chosen by Carter because of his prior knowledge of the terrain and his rapport with the indigenous people. Carter’s group consisted of 17 Europeans and a trained 350-strong local guerrilla force. Carter, who was known as Toby, was called King Carter by the locals. On the outbreak of war he joined the British Army – the colonial power before joining the RAE. He was polite and soft spoken and regarded as an idealist who never lost sight of the long game of fostering civilian administration where possible. However, Major Carter was a valiant soldier and attacking the invading forces of the Empire of Japan was his main focus. Carter was initially in charge of all the codenamed Semut operations in Borneo but ran a smaller group, Semut II which was nevertheless a substantial body of men. -

Spring 1992 State~ Executive{I~ \, • President's Message·

. I POSTAGE PAID .,... AUSTRALiA THE OFFICIAL JOURNAL OF THE RETURNED & SERVICES LEAGUE WA BRANCH (INCORPORATED) SPRING, 1992 Registered by Australia Post Publication No. WAS 1158 VOL. 15, ~o. 3- PRICE $1 Who said the AustraJ!an Flag ~ was not used in wwn Commonwealth Department <;>f Veterans' Affair.s Can ~ we help you? You could be eligible for benefits if • you are a veteran • a widow, wife or dependent child of a veteran, or • your spouse, parent or guardian is, or was, a veteran, or member of the Australian Defence or Peacekeeping forces. • you have completed qualifying peacetime service in the case of Defence Service Homes benefits. Veterans' benefits include: • Pensions and allowances • Health-care benefits • Counselling services • Pharmaceutical benefits • Defence Service Homes - housing loan subsidy - homeowners' insurance • Funeral benefits • Commemoration FIND OUT WHETHER YOU ARE ELIGIBLE FOll BENEFITS BY ·coNTACTING THE DEPARTMENT OF VETERANS' AFFAIRS ON 425 8222 .. --. ---- Country Callers Free Line: 008 113304 Remember .. .. "We're only a 'phone call away" Veterans' Affairs-Cares l:JISTENING;POST : Page ~ - . Publishers President's M css<t gc 3 ~ & Servicis lap W.A. Branch (looorporatcd) Anw: House G.P.O. Box Cl28, ~J 28 St. Georpi Tmace Perth, W.A. 60(11 0 on <t! 1 on s - 8 u i Id tng A ppl'CII · Ferib, · W.~ 6000 . Tel: 325·9799 In Defence of our Fl<tg 13 The Capture of Lac Part 3 16 The M(•t tlonous M ed<tl 17 Consumer F o! LUlls f o 1 the Ag!~d 3 1 '· '} Sub Br<tnch Offtce Bc<trers 37 D efe nce Issues 53 Veteran s· Affatrs 57 Editorial Committee Letter s to the Edtlor 59 Mrs H.P. -

On Sharks & Humanity the Search for Endeavour Krait and Operation Jaywick

Summer 2018–19 Number 125 December to February sea.museum $9.95 On Sharks & Humanity Art for social action The search for Endeavour What became of Cook’s famous ship? Krait and Operation Jaywick Marking the 75th anniversary Bearings Contents From the Director Summer 2018–19 Number 125 December to February sea.museum $9.95 THE AUSTRALIAN NATIONAL MARITIME MUSEUM was built Acknowledgment of country 2 On Sharks & Humanity more than 25 years ago, as a key attraction in the massive The Australian National Maritime An international travelling exhibition focuses on shark conservation regeneration of the former port of Darling Harbour. The blueprint Museum acknowledges the Gadigal people of the Eora nation as the 10 Endeavour returns to sea used for this waterfront rejuvenation was first employed in the traditional custodians of the bamal Berths now available for local and international voyages 1970s by town planners in Baltimore Harbour, USA, where instead (earth) and badu (waters) on which we work. of a national maritime museum, they built a national aquarium. 14 Piecing together a puzzle We also acknowledge all traditional The search for Cook’s Endeavour in Newport Harbour, Rhode Island Our museum lies within the country’s busiest tourist precinct, custodians of the land and waters 20 Refitting a raider which receives more than 25 million visits a year, and is also the throughout Australia and pay our respects to them and their cultures, Restoring MV Krait for the 75th anniversary of Operation Jaywick Australian government’s most visible national cultural institution in and to elders past and present. -

Edition 4 ~ 2020

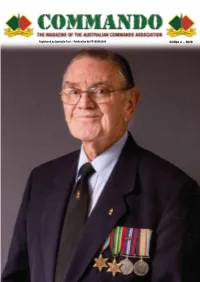

Registered by Australia Post ~ Publication No PP100016240 Edition 4 ~ 2020 CONTENTS REGISTERED BY AUSTRALIA POST PUBLICATION No PP100016240 Editor’s Word....................................................................3 National President’s Word ...............................................5 AUSTRALIAN COMMANDO ASSOCIATION INC. ACA NSW Report.............................................................7 LIFE PATRON: Gen Sir Phillip Bennett AC KBE DSO ACA QLD Report ...........................................................11 15 PATRON: MajGen Tim McOwan AO DSC CSM ACA VIC Report ............................................................. ACA WA Report .............................................................17 NATIONAL OFFICE BEARERS CDO Welfare Trust.........................................................18 PRESIDENT: MajGen Greg Melick AO RFD SC ACA Veterans Advocacy Update...................................19 VICE PRESIDENT: Maj Steve Pilmore OAM RFD (Ret’d) Significant Commando Dates ........................................23 SECRETARY: Maj John Thurgar SC MBE OAM RFD Commandos for Life ......................................................25 (Ret’d) Commando Vale .............................................................26 TREASURER: Maj Bruce O’Conner OAM RFD (Ret’d) The Last of the Very First...............................................30 PUBLIC OFFICER: Maj Brian Liddy (Retd) A Seamstress Goes to War in a Bathtub .......................32 Eight Men Dropped from the Skies (Part 3)..................34 STATE ASSOCIATION -

Phot Son of Bario.Cdr

A Japanese Naval officer who subsequently ‘died of wounds’ at Long Berang. The photo also includes the District Officer who helped Warrant Officer Cusack and Corporal Hardy. 50 Prahus entering the narrow rapids section on the Baram River. Parts of Sipitang remain unchanged since 1945. 51 Son of Bario 9 Sampson Bala-Palaba153 Being the son of a post-war Kelabit soldier, it was particularly hard distinguishing stories from my father's experience as a 11 year old cook for the late Tuan Mayur (Harrisson) and tales from his involvement during the Confrontation and Brunei Rebellion, let alone remembering what was considered folklore from the 1940s. Unlike the much-acclaimed British SAS, to this day, Z Special Force remains a mystery to most people. Being a wild man of the Borneo kind, who in my younger days dreamt of being a counter-revolutionary hero, I am fortunate to have laid my hands on some books and articles on Z Force which I enjoyed reading tremendously. My story is based upon facts heard and passed from generation to generation. Included too, are my personal views and reflection, which should not be generalised otherwise. In mid 1996, I had a letter from an anonymous Australian, stating his intention to retrace the Semut operations undertaken by Z Special Force during WWII (the Japanese War, as commonly referred to by locals). How he got my name and address, remains a mystery and until then, my only living memory of Z Special Force was the Maori Hakka. We were told that the dance was introduced by members of the 'Tentera Payung from Australia.' (tentera - army; payung - parachute).