Farewell to Manzanar WELCOME! OVERVIEW

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Acclaimed Author Jeanne Wakatsuki Houston's Book Celebrates 45 Years

THE NATIONAL NEWSPAPER OF THE JACL May 18-31, 2018 » PAGE 6 HOMECOMING FOR HOUSTON Acclaimed author Jeanne Wakatsuki Houston’s book celebrates 45 years and is chosen as the selection for the 16th annual Santa Monica Reads. » PAGE 5 » PAGES 8 AND 9 Arlington National Cemetery Set to Moving Recaps of the Poston Hold Its 70th Memorial Day Program and Rohwer/Jerome Pilgrimages WWW.PACIFICCITIZEN.ORG #3321 / VOL. 166, No. 9 ISSN: 0030-8579 2 May 18-31, 2018 SPRING CAMPAIGN LETTER/COMMUNITY HOW TO REACH US IT’S VITAL TO CONTINUE TO Email: [email protected] Online: www.pacificcitizen.org Tel: (213) 620-1767 Mail: 123 Ellison S. Onizuka St., SHARE OUR STORIES — Suite 313 Los Angeles, CA 90012 STAFF SPRING CAMPAIGN 2018 Executive Editor Allison Haramoto Senior Editor n a recent discussion with my cousin, like part of a community, even though I may not with their people.” The stories in each issue help Digital & Social Media Robin Hattori, we talked about the value of see those people ever again,” she said. us connect to our fellow Japanese Americans. George Johnston “being with your people.” She and I grew up I had been to Rohwer more than a decade Even those who are thousands of miles away still Business Manager Itogether in St. Louis, Mo., and we both still live earlier when I traveled there with my parents and feel like part of our community. Susan Yokoyama here. When we were teens, we found our people siblings. My cousin and I compared notes about As readers of the Pacific Citizen, we have a Production Artist in JAYS (Japanese American Youths), where all our experiences. -

Lesson 3 Activity 1 What Do You Know? Resources Section) and Give Students Five Minutes to Fill It out Individually

Manzanar National Historic Site How Does My Identity Shape My Experience in America? Activity 1: History of Japanese Americans How does war affect America’s identity? Objective: Students begin to explore the context surrounding the World War II internment of Japanese Americans. Grade Level: 10 & 11 Procedure: Time: 20 minutes Materials: Pass out the What Do You Know handout (located in the Lesson 3 Activity 1 What Do You Know? Resources section) and give students five minutes to fill it out individually. You handout may read the What Do You Know statements to the class and have them raise their hands to decide if they think the statement is true or false. Conduct a classroom discussion based on stereotypes and wording within the What Do You Know handout. In the guide, the word “Americans” is used. Define Americans. Concepts Covered: Do all Japanese Americans have a single culture or identity? Do they Assess students’ appear to be grouped together in the What Do You Know handout? background knowledge. Anticipate what Encourage students to verify students expect to learn. his/her answers throughout Assessment: Evaluate what they have the lessons. At the end of the 1. Participation in the What Do lessons, check the What Do You Know discussion. learned. You Know handout again and Fill out charts. see if all the questions have Extension: 1. Access the Densho Teacher been answered. If they In the Shadow of haven’t been answered, break Resource Guide, the statements up and have My Country: A Japanese American CDE Standards: Artist Remembers- Lesson 1 students find the answers. -

A Comparison of the Japanese American Internment Experience in Hawaii and Arkansas Caleb Kenji Watanabe University of Arkansas, Fayetteville

University of Arkansas, Fayetteville ScholarWorks@UARK Theses and Dissertations 12-2011 Islands and Swamps: A Comparison of the Japanese American Internment Experience in Hawaii and Arkansas Caleb Kenji Watanabe University of Arkansas, Fayetteville Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarworks.uark.edu/etd Part of the Asian American Studies Commons, Other History Commons, and the Public History Commons Recommended Citation Watanabe, Caleb Kenji, "Islands and Swamps: A Comparison of the Japanese American Internment Experience in Hawaii and Arkansas" (2011). Theses and Dissertations. 206. http://scholarworks.uark.edu/etd/206 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by ScholarWorks@UARK. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks@UARK. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected]. ISLANDS AND SWAMPS: A COMPARISON OF THE JAPANESE AMERICAN INTERNMENT EXPERIENCE IN HAWAII AND ARKANSAS ISLANDS AND SWAMPS: A COMPARISON OF THE JAPANESE AMERICAN INTERNMENT EXPERIENCE IN HAWAII AND ARKANSAS A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in History By Caleb Kenji Watanabe Arkansas Tech University Bachelor of Arts in History, 2009 December 2011 University of Arkansas ABSTRACT Comparing the Japanese American relocation centers of Arkansas and the camp systems of Hawaii shows that internment was not universally detrimental to those held within its confines. Internment in Hawaii was far more severe than it was in Arkansas. This claim is supported by both primary sources, derived mainly from oral interviews, and secondary sources made up of scholarly research that has been conducted on the topic since the events of Japanese American internment occurred. -

A Pictorial Visit of a Japanese Internment Camp

Manzanar: Evacuation or Incarceration: A Pictorial Visit of a Japanese Internment Camp by Melanie A. Mays Source – Author Overview: On February 19, 1942, President Roosevelt signed Executive Order 9066 giving the military authority to relocate those posing a potential threat to national security. This lesson will complement the reading of the novel Farewell to Manzanar by Jeanne Wakatsuki Houston, looking at the Japanese Internment Camp, Manzanar, in Owens Valley, California during World War II. Specifically, the lesson will tie the novel (a primary non-fiction source) to two other primary sources, the photos of Ansel Adams and Dorothea Lange. National Geography Standards: Geography Standard 13 – Conflict How the forces of cooperation and conflict among people influence the division and control of Earth's surface. The geographically informed person must understand how and why different groups of people have divided, organized, and unified areas of Earth's surface. Competing for control of areas of Earth's surface, large and small, is a universal trait among societies and has resulted in both productive cooperation and destructive conflict between groups. Conflicts over trade, human migration and settlement, ideologies and religions, and exploitation of marine and land environments reflect how Earth's surface is divided into fragments controlled by different formal and informal political, economic, and cultural interest groups. 1 The student knows and understands: • Conflicts arise when there is disagreement over the division, control, and management of Earth's surface. • There are multiple sources of conflict resulting from the division of Earth's surface. • Changes within, between, and among countries regarding division and control of Earth's surface may result in conflicts. -

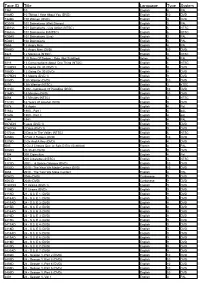

Tape ID Title Language Type System

Tape ID Title Language Type System 1361 10 English 4 PAL 1089D 10 Things I Hate About You (DVD) English 10 DVD 7326D 100 Women (DVD) English 9 DVD KD019 101 Dalmatians (Walt Disney) English 3 PAL 0361sn 101 Dalmatians - Live Action (NTSC) English 6 NTSC 0362sn 101 Dalmatians II (NTSC) English 6 NTSC KD040 101 Dalmations (Live) English 3 PAL KD041 102 Dalmatians English 3 PAL 0665 12 Angry Men English 4 PAL 0044D 12 Angry Men (DVD) English 10 DVD 6826 12 Monkeys (NTSC) English 3 NTSC i031 120 Days Of Sodom - Salo (Not Subtitled) Italian 4 PAL 6016 13 Conversations About One Thing (NTSC) English 1 NTSC 0189DN 13 Going On 30 (DVD 1) English 9 DVD 7080D 13 Going On 30 (DVD) English 9 DVD 0179DN 13 Moons (DVD 1) English 9 DVD 3050D 13th Warrior (DVD) English 10 DVD 6291 13th Warrior (NTSC) English 3 nTSC 5172D 1492 - Conquest Of Paradise (DVD) English 10 DVD 3165D 15 Minutes (DVD) English 10 DVD 6568 15 Minutes (NTSC) English 3 NTSC 7122D 16 Years Of Alcohol (DVD) English 9 DVD 1078 18 Again English 4 Pal 5163a 1900 - Part I English 4 pAL 5163b 1900 - Part II English 4 pAL 1244 1941 English 4 PAL 0072DN 1Love (DVD 1) English 9 DVD 0141DN 2 Days (DVD 1) English 9 DVD 0172sn 2 Days In The Valley (NTSC) English 6 NTSC 3256D 2 Fast 2 Furious (DVD) English 10 DVD 5276D 2 Gs And A Key (DVD) English 4 DVD f085 2 Ou 3 Choses Que Je Sais D Elle (Subtitled) French 4 PAL X059D 20 30 40 (DVD) English 9 DVD 1304 200 Cigarettes English 4 Pal 6474 200 Cigarettes (NTSC) English 3 NTSC 3172D 2001 - A Space Odyssey (DVD) English 10 DVD 3032D 2010 - The Year -

Chapter 8 Manzanar

CHAPTER 8 MANZANAR Introduction The Manzanar Relocation Center, initially referred to as the “Owens Valley Reception Center”, was located at about 36oo44' N latitude and 118 09'W longitude, and at about 3,900 feet elevation in east-central California’s Inyo County (Figure 8.1). Independence lay about six miles north and Lone Pine approximately ten miles south along U.S. highway 395. Los Angeles is about 225 miles to the south and Las Vegas approximately 230 miles to the southeast. The relocation center was named after Manzanar, a turn-of-the-century fruit town at the site that disappeared after the City of Los Angeles purchased its land and water. The Los Angeles Aqueduct lies about a mile to the east. The Works Progress Administration (1939, p. 517-518), on the eve of World War II, described this area as: This section of US 395 penetrates a land of contrasts–cool crests and burning lowlands, fertile agricultural regions and untamed deserts. It is a land where Indians made a last stand against the invading white man, where bandits sought refuge from early vigilante retribution; a land of fortunes–past and present–in gold, silver, tungsten, marble, soda, and borax; and a land esteemed by sportsmen because of scores of lakes and streams abounding with trout and forests alive with game. The highway follows the irregular base of the towering Sierra Nevada, past the highest peak in any of the States–Mount Whitney–at the western approach to Death Valley, the Nation’s lowest, and hottest, area. The following pages address: 1) the physical and human setting in which Manzanar was located; 2) why east central California was selected for a relocation center; 3) the structural layout of Manzanar; 4) the origins of Manzanar’s evacuees; 5) how Manzanar’s evacuees interacted with the physical and human environments of east central California; 6) relocation patterns of Manzanar’s evacuees; 7) the fate of Manzanar after closing; and 8) the impact of Manzanar on east central California some 60 years after closing. -

A Conversation on Japanese American Incarceration & Its Relevance to Today

CONVERSATION KIT Courtesy of the National Archives Tuesday, May 17, 2016 1:00-2:00 pm EDT, 10:00-11:00 am PDT Smithsonian National Museum of American History Kenneth E. Behring Center IN WORLD WAR II NATIONAL YOUTH SUMMIT JAPANESE AMERICAN INCARCERATION 2 TABLE OF CONTENTS SECTION I: INTRODUCTION TO THE NATIONAL SUMMIT . 3 Introduction . 3 Program Details . 4 Regional Summit Locations . 4 When, Where, and How to Participate . 4 Join the Conversation . 5 Central Questions . 6 Panelists and Participants . 7 Common Core State Standards . 9 National Standards for History . 10 SECTION II: LANGUAGE . 11 Statement on Terminology . 12 SECTION III: LESSON PLANS . 14 Lesson Plans and Resources on Japanese American Incarceration . 15 Lesson Ideas for Japanese American Incarceration and Modern Parallels . 17 SECTION IV: YOUTH LEADERSHIP AND TAKING ACTION . 18 What Can You Do? . 19 SECTION V: ADDITIONAL RESOURCES . .. 21 NATIONAL YOUTH SUMMIT JAPANESE AMERICAN INCARCERATION 3 SECTION I: INTRODUCTION TO THE NATIONAL SUMMIT Thank you for participating in the Smithsonian’s National Youth Summit on Japanese American Incarceration. This Conversation Kit is designed to provide you with lesson activities and ideas for leading group discussions on the issues surrounding Japanese American incarceration and their relevance today. This kit also provides details on ways to participate in the Summit. The National Youth Summit is a program developed by the National Museum of American History in collaboration with Smithsonian Affiliations. This program is funded by the Smithsonian’s Youth Access Grants. Pamphlet, Division of Armed Forces History, Office of Curatorial Affairs, National Museum of American History Smithsonian Smithsonian National Museum of American History National Museum of American History Kenneth E. -

Lost Years 1942-46 Lost Years 1942-46

THE LOST YEARS 1942-46 LOST YEARS 1942-46 Edited by Sue Kunitomi Embrey Moonlight Publications; Gidra, Inc., Los Angeles, California Photo by Boku Kodama In January, 1972, the California State Department of Parks and Recrea tion approved Manzanar as a historic landmark. The final wording as it appears on the plaque (see picture above) was agreed upon after a year of controversy and negotiations. The Manzanar Pilgrimage of April 14, 1973, dedicating the plaque, attracted over 1500 participants. Copyright ® 1972 by the Manzanar Committee All rights reserved, including the right to reproduce this book or portions thereof in any form, without written permission from the Publisher. First Printing: March, 1972 Fourth Printing: May, 1982 Second Printing: June, 1972 Fifth Printing: November, 1987 Third Printing: March, 1976 Manzanar Committee, Los Angeles 1566 Curran Street Los Angeles, Calif. 90026 Printed in the United States of America TABLE OF CONTENTS 2 Introduction 5 A Chronology of Evacuation and Relocation 15 Why It Happened Here by Roger Daniels 37 Manzanar, a poem by Michi 38 Life in a Relocation Center 44 Untitled Poem by James Shinkai 45 Segregation of Persons of Japanese Ancestry in Relocation Centers 51 Why Relocate? 56 Bibliography PHOTOGRAPHS cover Manzanar Cemetery Monument 4 Evacuees entering one of the camps 14 Sentry Tower 28-29 Barracks at Manzanar 36 Young men looking out behind Manzanar's barbed wire 48 Newspaper headlines before Evacuation 60 National Park Service historic plaque Cover: The Manzanar Cemetery monument designed and built by R.F. Kado, a landscape architect and stone mason, was completed in August, 1943. -

Living Voices Within the Silence Bibliography 1

Living Voices Within the Silence bibliography 1 Within the Silence bibliography FICTION Elementary So Far from the Sea Eve Bunting Aloha means come back: the story of a World War II girl Thomas and Dorothy Hoobler Pearl Harbor is burning: a story of World War II Kathleen Kudlinski A Place Where Sunflowers Grow (bilingual: English/Japanese) Amy Lee-Tai Baseball Saved Us Heroes Ken Mochizuki Flowers from Mariko Rick Noguchi & Deneen Jenks Sachiko Means Happiness Kimiko Sakai Home of the Brave Allen Say Blue Jay in the Desert Marlene Shigekawa The Bracelet Yoshiko Uchida Umbrella Taro Yashima Intermediate The Burma Rifles Frank Bonham My Friend the Enemy J.B. Cheaney Tallgrass Sandra Dallas Early Sunday Morning: The Pearl Harbor Diary of Amber Billows 1 Living Voices Within the Silence bibliography 2 The Journal of Ben Uchida, Citizen 13559, Mirror Lake Internment Camp Barry Denenberg Farewell to Manzanar Jeanne and James Houston Lone Heart Mountain Estelle Ishigo Itsuka Joy Kogawa Weedflower Cynthia Kadohata Boy From Nebraska Ralph G. Martin A boy at war: a novel of Pearl Harbor A boy no more Heroes don't run Harry Mazer Citizen 13660 Mine Okubo My Secret War: The World War II Diary of Madeline Beck Mary Pope Osborne Thin wood walls David Patneaude A Time Too Swift Margaret Poynter House of the Red Fish Under the Blood-Red Sun Eyes of the Emperor Graham Salisbury, The Moon Bridge Marcia Savin Nisei Daughter Monica Sone The Best Bad Thing A Jar of Dreams The Happiest Ending Journey to Topaz Journey Home Yoshiko Uchida 2 Living Voices Within the Silence bibliography 3 Secondary Snow Falling on Cedars David Guterson Hotel on the Corner of Bitter and Sweet Jamie Ford Before the War: Poems as they Happened Drawing the Line: Poems Legends from Camp Lawson Fusao Inada The moved-outers Florence Crannell Means From a Three-Cornered World, New & Selected Poems James Masao Mitsui Chauvinist and Other Stories Toshio Mori No No Boy John Okada When the Emperor was Divine Julie Otsuka The Loom and Other Stories R.A. -

For Free Public Book Discussion Groups and Other Events, Check the *City of Santa Monica Facilities Are Wheelchair Accessible

An Afternoon with Jeanne Wakatsuki Houston The Japanese Flower Market: Sat, May 12 at 2:0 0pm | Main Library, MLK Jr. Auditorium Presentation & Workshop Author Jeanne Wakatsuki Houston opens the 16th year of Santa Monica Sun, June 10 at 2:0 0pm | Main Library, Multipurpose Room Reads with a discussion of Farewell to Manzanar and her connections to Naomi Hirahara, author o f A Scent of Flowers: The History of the Southern Santa Monica, and shares her thoughts on how the book and her family’s California Flower Market 1912-2004 , discusses the contributions of story resonate in today’s world. A book signing follows. Japanese Americans and other ethnic Americans to the local floriculture industry. A book sale and signing follows, along with a mini flower Family Origami Workshop with Peggy Hasegawa arranging workshop (supplies limited). Thu, May 17 at 6:0 0pm | Montana Avenue Branch Papermaker, bookmaker, and origami artist Peggy Hasegawa teaches simple Movie: Farewell to Manzanar (1976) origami techniques to fold and create amazing paper objects. For ages 6 Tue, June 12 at 6:3 0pm | Ocean Park Branch and up. All supplies provided. Nominated for two Emmy Awards, the adaptation of Jeanne Wakatsuki Houston and James D. Houston’s book stars the best-known Japanese Barbed Wire to Boogie Woogie: Swing in the and Japanese American actors of the time, including Pat Morita and Nobu Japanese American Internment Camps McCarthy. Many Americans first learned of the internment camps through Sat, May 19 at 2:0 0pm this televised drama. (107 min.) Main Library, MLK Jr. -

Then They Came for Me Incarceration of Japanese Americans During WWII and the Demise of Civil Liberties ALPHAWOOD GALLERY, CHICAGO JUNE 29 to NOVEMBER 19, 2017

Then They Came for Me Incarceration of Japanese Americans during WWII and the Demise of Civil Liberties ALPHAWOOD GALLERY, CHICAGO JUNE 29 TO NOVEMBER 19, 2017 ALPHAWOOD FOUNDATION STATEMENT Alphawood Foundation is the proud sponsor of the exhibition Then They Came for Me: Incarceration of Japanese Americans during WWII and the Demise of Civil Liberties. Why did we feel it was important to share this story with the Chicago community? Alphawood exists to help create a more equitable, just and humane society for all of us. A difficult but essential part of that mission is to shine a light on great injustice, great inhumanity and great failure to live up to the core principles underlying our society. Then They Came for Me presents the shameful story of the United States government’s imprisonment of 120,000 people, most of them American citizens, solely based on their ethnic background. Think about that. Then think about what is occurring in our country right now, and what might be just around the corner. George Santayana wrote “those who cannot remember the past are condemned to repeat it.” The Japanese American incarceration represents a moment when we collectively turned our backs on the great promise and responsibility of our Constitution. We denied equal protection under the law to our fellow Americans and legal residents because of their ancestry alone. We tell this story because we love our country. We care deeply about its past, present and future. We know that America is better than the racism and xenophobia that triggered the events depicted in this exhibition. -

The Life of David Gale

Wettbewerb/IFB 2003 THE LIFE OF DAVID GALE DAS LEBEN DES DAVID GALE THE LIFE OF DAVID GALE Regie:Alan Parker USA 2002 Darsteller David Gale Kevin Spacey Länge 131 Min. Bitsey Bloom Kate Winslet Format 35 mm, Constance Harraway Laura Linney Cinemascope Zack Stemmons Gabriel Mann Farbe Dusty Wright Matt Craven Braxton Belyeu Leon Rippy Stabliste Berlin Rhona Mitra Buch Charles Randolph Nico Melissa McCarthy Kamera Michael Seresin Duke Grover Jim Beaver Kameraführung Mike Proudfoot Barbara Kreuster Cleo King Edward J.Adcock A.J.Roberts Constance Jones Kameraassistenz Bill Coe Joe Mullarkey Lee Ritchey Schnitt Gerry Hambling Jamie Gale Noah Truesdale Ton David McMillan Greer Chuck Cureau Musik Alex Parker Ross Sean Hennigan Jake Parker John Charles Sanders Production Design Geoffrey Kirkland Talkmaster Marco Perella Ausstattung Steve Arnold Gouverneur Hardin Michael Crabtree Jennifer Williams Sharon Gale Elizabeth Gast Requisite Don Miloyevich Laura Linney, Kevin Spacey Universitätspräsident Cliff Stephens Kostüm Renée Ehrlich Kalfus Maske Sarah Monzani Regieassistenz K.C.Hodenfield DAS LEBEN DES DAVID GALE Casting Juliet Taylor Dr.David Gale ist Professor an einer texanischen Universität – ein liebevoller Howard Feuer Vater und anerkannter Akademiker, der aus seinen Überzeugungen nie ein Herstellungsltg. David Wimbury Hehl gemacht hat. Dr. Gale ist ein engagierter Gegner der Todesstrafe und Produktionsltg. Alma Kuttruff als solcher wird er weithin respektiert. Doch dann geschieht das Unfassba- Produzenten Alan Parker Nicolas Cage re: Er wird angeklagt, Constance Harraway, eine junge Mitstreiterin, die ihn Executive Producers Moritz Borman in seinem Kampf um das Leben eines Verurteilten unterstützt hat, verge- Guy East waltigt und ermordet zu haben. Der Richter verurteilt ihn zum Tode.