Alaska's Wild Salmon

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

SUSTAINABLE FISHERIES and RESPONSIBLE AQUACULTURE: a Guide for USAID Staff and Partners

SUSTAINABLE FISHERIES AND RESPONSIBLE AQUACULTURE: A Guide for USAID Staff and Partners June 2013 ABOUT THIS GUIDE GOAL This guide provides basic information on how to design programs to reform capture fisheries (also referred to as “wild” fisheries) and aquaculture sectors to ensure sound and effective development, environmental sustainability, economic profitability, and social responsibility. To achieve these objectives, this document focuses on ways to reduce the threats to biodiversity and ecosystem productivity through improved governance and more integrated planning and management practices. In the face of food insecurity, global climate change, and increasing population pressures, it is imperative that development programs help to maintain ecosystem resilience and the multiple goods and services that ecosystems provide. Conserving biodiversity and ecosystem functions are central to maintaining ecosystem integrity, health, and productivity. The intent of the guide is not to suggest that fisheries and aquaculture are interchangeable: these sectors are unique although linked. The world cannot afford to neglect global fisheries and expect aquaculture to fill that void. Global food security will not be achievable without reversing the decline of fisheries, restoring fisheries productivity, and moving towards more environmentally friendly and responsible aquaculture. There is a need for reform in both fisheries and aquaculture to reduce their environmental and social impacts. USAID’s experience has shown that well-designed programs can reform capture fisheries management, reducing threats to biodiversity while leading to increased productivity, incomes, and livelihoods. Agency programs have focused on an ecosystem-based approach to management in conjunction with improved governance, secure tenure and access to resources, and the application of modern management practices. -

Atlantic Salmon Alert

ALERT FOR ATLANTIC SALMON IN SOUTHEAST ALASKA WATERS Please report any observations of this non-native species to the nearest ADF&G office. Over the past few years, ADF&G has verified harvests of Atlantic salmon in Southeast Alaska salt waters. Atlantic salmon are not native to the Pacific Ocean; they are raised in areas along the West Coast outside of Alaska, and their presence in Southeast Alaska waters is biologically undesirable. Anglers have reported catching Atlantic salmon in several of Southeast Alaska's freshwater systems. Alaska sport fishing regulations do not limit harvest of Atlantic salmon, but if you catch one, you can help us determine their status by bringing the entire fish to the nearest ADF&G office for biological sampling. The illustrations below will help you distinguish Atlantic salmon from native Alaska species. Irregular-shaped spots on back, dorsal fin, Small black spots Uniform spots on tail Steelhead Trout King Salmon and tail Silver Short head Square tail Small eye tail Slender lateral Thick caudal 8-12 anal fin rays Wide caudal Black mouth with profile black gums 13-19 anal fin rays Photograph courtesy of Washington Department Washington Photograph courtesy of Wildlife. of Fish and Atlantic Salmon Black x-shaped No spots on tail Caudal is slender spots above lateral or “pinched” line, large scales Large black spots on gill May, or may cover not, have spots on tail Upper lip does not Spots on tail extend past rear of 8-12 anal fin Body tapered at head and tail eye rays Tydingco. Troy Atlantic salmon photographs -

Snohomish River Basin Salmon Conservation Plan: Status and Trends

SNOHOMISH RIVER BASIN SALMON CONSERVATION PLAN STATUS AND TRENDS DECEMBER 2019 CONTENTS Introduction 1 Status Update 3 Snohomish Basin 3 Salmon Plan Overview 7 Implementation Progress 10 Status and Trends 18 Salmon in the Basin 18 Chinook Salmon 19 Coho Salmon 22 Steelhead 24 Bull Trout 26 Chum Salmon 27 Factors Affecting Survival of Salmon Species 29 Basin Trends 32 Salmon Plan Implementation 46 Habitat Restoration Progress 48 Restoration Funding 67 Habitat and Hydrology Protection Observations 70 Monitoring and Adaptive Management 76 Updating the Basin-Wide Vision for Recovery 77 Considerations for a Changing Future 78 Restoration Opportunities and Challenges 82 Integration of Habitat, Harvest, and Hatchery Actions Within the Basin 86 Multi-Objective Planning 88 Updating Our Salmon Plan 90 Credits and Acknowledgments 93 INTRODUCTION Since 1994 — 5 years before the Endangered Species Act (ESA) listing of Chinook salmon — partner organizations in the Snohomish Basin have been coordinating salmon recovery efforts to improve salmon stock numbers. In 2005, the Snohomish Basin Salmon Recovery Forum (Forum) adopted the Snohomish River Basin Salmon Conservation Plan1 (Salmon Plan), defining a multi-salmon strategy for the Snohomish Basin that emphasizes two ESA-listed species, Chinook salmon and bull trout, and the non-listed coho salmon. These species are used as proxies for other Basin salmon to help prevent future listings. The Salmon Plan, developed by the 41-member Forum, incorporates habitat, harvest, and hatchery management actions to bring the listed wild stocks back to healthy, harvestable levels. 1 Snohomish Basin Salmon Recovery Forum, 2005. Snohomish River Basin Salmon Conservation Plan. Snohomish County Department of Public Works, Surface Water Management Division. -

Thailand's Shrimp Culture Growing

Foreign Fishery Developments BURMA ':.. VIET ,' . .' NAM LAOS .............. Thailand's Shrimp ...... Culture Growing THAI LAND ,... ~samut Sangkhram :. ~amut Sakorn Pond cultivation ofblacktigerprawns, khlaarea. Songkhla's National Institute '. \ \ Bangkok........· Penaeus monodon, has brought sweep ofCoastal Aquaculture (NICA) has pro , ••~ Samut prokan ing economic change over the last2 years vided the technological foundation for the to the coastal areas of Songkhla and establishment of shrimp culture in this Nakhon Si Thammarat on the Malaysian area. Since 1982, NICA has operated a Peninsula (Fig. 1). Large, vertically inte large shrimp hatchery where wild brood grated aquaculture companies and small stock are reared on high-quality feeds in .... Gulf of () VIET scale rice farmers alike have invested optimum water temperature and salinity NAM heavily in the transformation of paddy conditions. The initial buyers ofNICA' s Thailand fields into semi-intensive ponds for shrimp postlarvae (pI) were small-scale Nakhon Si Thammarat shrimp raising. Theyhave alsodeveloped shrimp farmers surrounding Songkhla • Hua Sai Songkhla an impressive infrastructure ofelectrical Lake. .. Hot Yai and water supplies, feeder roads, shrimp Andaman hatcheries, shrimp nurseries, feed mills, Background Sea cold storage, and processing plants. Thailand's shrimp culture industry is Located within an hour's drive ofSong the fastest growing in Southeast Asia. In khla's new deep-waterport, the burgeon only 5 years, Thailand has outstripped its Figure 1.-Thailand and its major shrimp ing shrimp industry will have direct competitors to become the region's num culture area. access to international markets. Despite ber one producer. Thai shrimp harvests a price slump since May 1989, expansion in 1988 reached 55,000 metric tons (t), onall fronts-production, processingand a 320 percent increase over the 13,000 t marketing-continues at a feverish pace. -

Krill Oil and Astaxanthin

Krill Oil and Astaxanthin Krill are small reddish-color crustaceans, similar to shrimp, that abound in cold Arctic waters. They survive in such cold, frigid temperatures because of their natural anti- freeze, the polyunsaturated fatty acids EPA and DHA. EPA and DHA are bound to molecules called phospholipids (especially phosphatidyl choline) that act to help transport nutrients into cells and change the structure of animal cell membranes. Studies show that these combined fatty acids have better absorption into the cell membranes throughout the body, especially the brain, as compared to other types of fish oils. Although it has less EPA/DHA content than most fish oils, krill oil seems to be almost twice as absorbable. Unlike fish oil, krill oil also contains a very potent antioxidant, astaxanthin, which helps prevent krill oil from oxidizing (turning rancid). Astaxanthin is a red pigment found in different types of algae and phytoplankton. It is astaxanthin that gives salmon and trout their reddish color. It is considered to be one of the most potent natural antioxidants, almost 50 times stronger than beta-carotenes found in fruits and vegetables and 65 times better as an anti-oxidant than vitamin C. Krill oil is composed of 40% phospholipids, 30% EPA and DHA, astaxanthin, vitamin A, vitamin C, various other fatty acids, and flavanoids (anti-oxidant compounds) Human studies indicate krill oil is powerful at decreasing inflammation throughout the body, especially in the brain. It reduces C-reactive protein, a marker for heart disease. Tests indicate it has a powerful anti-inflammatory remedy for rheumatoid as well as osteoarthritis. -

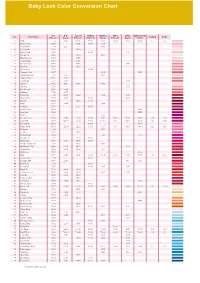

Baby Lock Color Conversion Chart

Tacony_quickguide_37-コピー 05.7.6 9:01 AM ページ 37 Baby Lock Color Conversion Chart R.A. R.A. Isacord Madeira Madeira Sulky Sulky Güetermann No. Color Name Polyester Rayon Polyester Polyneon Rayon Polyester Rayon Dekor Country Embr. 1 Pink 5523 2223 *0180 1921 1121 1224 1108 *4830 155 085 2 Dusty Rose 5675 2155 1816 1108 3 Petal Pink 7701 2255 1015 4 Light Pink 9030 1860 5 Light Coral 9078 1915 1148 6 Ginger Jar 9080 2170 1115 7 Heather Mist 9070 1755 8 Champagne 9063 2051 9 Dark Mauve 9015 2153 1119 10 Heather 9164 2152 11 Neon Pink 5711 1948 12 Comfort Pink 9077 1119 5435 13 Mountain Rose 5795 2373 1315 14 Cherry Pink 5544 2244 15 Carnation 5537 2509 1188 16 Salmon 9073 2553 1840 1018 17 Shrimp 5546 1154 18 Dark Coral 9065 2246 19 Bitteroot 7709 2277 20 Burgundy 5549 2249 2022 1182 1169 21 Warm Wine 5796 2622 1782 1309 22 Russet 5552 2123 1781 23 Plum 9055 2498 1389 24 Maroon 5676 2115 1919 25 Royal Crest 9162 5400 26 Hot Pink 5560 5385 27 Ruby 5797 1183 28 Dark Fuchsia 5804 2504 *2300 1984 1383 1533 1533 *4810 126 107 29 Carmine 5561 *2419 2300 1986 *1081 1511 *1511 5315 158 807 30 Dark Pink 9161 1994 4810 31 Deep Rose 9168 *2508 2520 1721 *1117 1154 1307 *4941 024 086 32 Begonia 5528 1117 33 Azalea 7712 2220 34 Rubine Red 9012 1186 4740 35 Strawberry 5732 2320 1910 36 Devil Red 7706 2507 1906 1986 37 Candy Apple Red 5807 1805 1081 38 Hollyhock Red 9006 2267 1912 1311 39 Toasty Red 9002 2418 1902 1181 40 Wild Fire 5567 4700 41 Red 5678 2505 2101 1637 *1037 1037 *1037 *4740 149 800 42 Jockey Red 5581 1747 43 Radiant Red 5566 2219 561 4731 -

Edna Assay Development

Environmental DNA assays available for species detection via qPCR analysis at the U.S.D.A Forest Service National Genomics Center for Wildlife and Fish Conservation (NGC). Asterisks indicate the assay was designed at the NGC. This list was last updated in June 2021 and is subject to change. Please contact [email protected] with questions. Family Species Common name Ready for use? Mustelidae Martes americana, Martes caurina American and Pacific marten* Y Castoridae Castor canadensis American beaver Y Ranidae Lithobates catesbeianus American bullfrog Y Cinclidae Cinclus mexicanus American dipper* N Anguillidae Anguilla rostrata American eel Y Soricidae Sorex palustris American water shrew* N Salmonidae Oncorhynchus clarkii ssp Any cutthroat trout* N Petromyzontidae Lampetra spp. Any Lampetra* Y Salmonidae Salmonidae Any salmonid* Y Cottidae Cottidae Any sculpin* Y Salmonidae Thymallus arcticus Arctic grayling* Y Cyrenidae Corbicula fluminea Asian clam* N Salmonidae Salmo salar Atlantic Salmon Y Lymnaeidae Radix auricularia Big-eared radix* N Cyprinidae Mylopharyngodon piceus Black carp N Ictaluridae Ameiurus melas Black Bullhead* N Catostomidae Cycleptus elongatus Blue Sucker* N Cichlidae Oreochromis aureus Blue tilapia* N Catostomidae Catostomus discobolus Bluehead sucker* N Catostomidae Catostomus virescens Bluehead sucker* Y Felidae Lynx rufus Bobcat* Y Hylidae Pseudocris maculata Boreal chorus frog N Hydrocharitaceae Egeria densa Brazilian elodea N Salmonidae Salvelinus fontinalis Brook trout* Y Colubridae Boiga irregularis Brown tree snake* -

Russian River Sockeye Salmon Study. Alaska Department of Fish And

Volume 21 Study AFS 43-5 STATE OF ALASKA Jay S. Hammond, Governor Annual Performance Report for RUSSIAN RIVER SOCKEYE SALMON STUDY David C. Nelson ALASKA DEPARTMENT OF FISH AND GAME Ronald 0. Skoog, Commissioner SPORT FISH DIVISION Rupert E. Andrews, Director TABLE OF CONTENTS Page Abstract .............................. 1 Background ............................. 2 Recommendations ...........................6 Objectives ............................. 9 TechniquesUsed .......................... 9 Findings .............................. 10 Smolt Investigations ....................... 10 Creelcensus ........................... 11 Escapement ............................ 17 Relationship of Jacks to Adults ................. 22 Migrational Timing in the Kenai River .............. 22 Managementofthe 1979Fishery .................. 26 Russian River Fish Pass ..................... 31 AgeClass Composition ...................... 32 Early Run Return per Spawner ................... 34 EggDeposition .......................... 40 Fecundity Investigations ..................... 40 Climatological Observations ................... 45 Literature Cited .......................... 45 LIST OF TABLES Table 1. List of Fish Species in the Russian River Drainage .... 8 Table 2. Outmigration of Russian River Sockeye Salmon Smolts by Five-Day Period. 1979 ................. 12 Table 3 . Summary of Sockeye Salmon Smolts Age. Length and Weight Data. 1979 ........................ 13 Table 4. Age Class Composition of the 1979 Sockeye Salmon Smolts Outmigration ...................... -

Diel Horizontal Migration in Streams: Juvenile fish Exploit Spatial Heterogeneity in Thermal and Trophic Resources

Ecology, 94(9), 2013, pp. 2066–2075 Ó 2013 by the Ecological Society of America Diel horizontal migration in streams: Juvenile fish exploit spatial heterogeneity in thermal and trophic resources 1,5 1 1,2 3 1 JONATHAN B. ARMSTRONG, DANIEL E. SCHINDLER, CASEY P. RUFF, GABRIEL T. BROOKS, KALE E. BENTLEY, 4 AND CHRISTIAN E. TORGERSEN 1School of Aquatic and Fishery Sciences, Box 355020, University of Washington, Seattle, Washington 98195 USA 2Skagit River System Cooperative, 11426 Moorage Way, La Conner, Washington 98257 USA 3Fish Ecology Division, Northwest Fisheries Science Center, National Marine Fisheries Service, National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, Seattle, Washington 98112 USA 4U.S. Geological Survey, Forest and Rangeland Ecosystem Science Center, Cascadia Field Station, School of Environmental and Forest Sciences, University of Washington, Seattle, Washington 98195 USA Abstract. Vertical heterogeneity in the physical characteristics of lakes and oceans is ecologically salient and exploited by a wide range of taxa through diel vertical migration to enhance their growth and survival. Whether analogous behaviors exploit horizontal habitat heterogeneity in streams is largely unknown. We investigated fish movement behavior at daily timescales to explore how individuals integrated across spatial variation in food abundance and water temperature. Juvenile coho salmon made feeding forays into cold habitats with abundant food, and then moved long distances (350–1300 m) to warmer habitats that accelerated their metabolism and increased their assimilative capacity. This behavioral thermoregulation enabled fish to mitigate trade-offs between trophic and thermal resources by exploiting thermal heterogeneity. Fish that exploited thermal heterogeneity grew at substantially faster rates than did individuals that assumed other behaviors. -

Marine Fish Culture

FAU Institutional Repository http://purl.fcla.edu/fau/fauir This paper was submitted by the faculty of FAU’s Harbor Branch Oceanographic Institute. Notice: © 1998 Kluwer. This manuscript is an author version with the final publication available and may be cited as: Tucker, J. W., Jr. (1998). Marine fish culture. Boston: Kluwer Academic Publishers. MARINE FISH CULTURE by John W. Tucker, Jr., Ph.D. Harbor Branch Oceanographic Institution and Florida Institute of Technology, Melbourne KLUWER ACADEMIC PUBLISHERS Boston I Dordrecht I London Distributors for North, Central and South America: Kluwer Academic Publishers I 01 Philip Drive Assinippi Park Norwell, Massachusetts 02061 USA Telephone (781) 871-6600 Fax (781) 871-6528 E-Mail <[email protected]> Distributors for all other countries: Kluwer Academic Publishers Group Distribution Centre Post Office Box 322 3300 AH Dordrecht, THE NETHERLANDS Telephone 31 78 6392 392 Fax 31 78 6546 474 E-Mail <[email protected]> '' Electronic Services <http://www.wkap.nl> Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Tucker, John W., 1948- Marine fish culture I by John W. Tucker, Jr. p. em. Includes bibliographical references (p. ) and index. ISBN 0-412-07151-7 (alk. paper) 1. Marine fishes. 2. Fish-culture. I. Title. SH163.T835 1998 639.3'2--dc21 98-42062 CIP Copyright © 1998 by Kluwer Academic Publishers All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means, mechanical, photo copying, recording, or otherwise, without the prior written permission of the publisher, Kluwer Academic Publishers, I 0 I Philip Drive, Assinippi Park, Norwell, Massachusetts 02061 Printed on acid-free paper. -

Vermilion Category: Alchemy Therasia Von Tux, Barony 1000 Eyes Specific Art Form: Pigment This Is the Sept 2001 Revised Edition (One Small “Oops” Corrected)

Vermilion Category: Alchemy Therasia von Tux, Barony 1000 Eyes specific art form: pigment this is the Sept 2001 revised edition (one small “oops” corrected) Entry contents: 1 vial vermilion/cinnabar (POISON!!! PLEASE DON"T OPEN THE BOTTLE) 1 piece cinnabar 1 copy of Artists' Pigments, for the Gettens et al. article (a copy of Cennini can be found with my "St. George" shield, in the Fine Arts category; copies of Pliny and Theophilus can be found with my silver entry, in the Alchemy category) A piece of cinnabar collected by a friend and on display at the McLaughlin Mine, Napa Co., CA (It's a lot prettier than most of my samples) The first known mention of mercuric sulfide as a mineral is in Theophratus's Lapidary. Theophrastus called it cinnabar, which is the name still in use today. The Romans called it minium, and it was so valuable as a red pigment that the Roman government made it a nationalized monopoly and regulated the price.1 It does need to be said that the Romans used the name minium for any high-quality mineral red, regardless of whether it was cinnabar or hematite.2 Minium was being adultrated with "red lead" as early as Imperial Rome, though it is difficult to determine whether Pliny meant red litharge or lead carbonate. Adulteration continued until the name shifted, and came to mean just red lead by Early Gothic. 3, 4 1 Pliny, Book XXXIII: sections XXXVI-XLI, using the Loeb numbering system. 2 Ibid. 3 Ibid. 4 Though historians would quibble about this, I tend to prefer to the art history divisions of history rather than the academic history divisions. -

Groundwater As Essential Salmon Habitat in Nushagak and Kvichak River Headwaters: Issues Relative to Mining

Groundwater as Essential Salmon Habitat In Nushagak and Kvichak River Headwaters: Issues Relative to Mining Dr. Carol Ann Woody and Dr. Brentwood Higman for CSP2 10 July 2011 Groundwater as Essential Salmon Habitat in Nushagak and Kvichak River Headwaters: Issues Relative to Mining Dr. Carol Ann Woody Fisheries Research and Consulting www.fish4thefuture.com Dr. Brentwood Higman Ground Truth Trekking http://www.groundtruthtrekking.org/ Abstract Groundwater-fed streams and rivers are among the most important fish habitats in Alaska because groundwater determines extent and volume of ice-free winter habitat. Sockeye, Chinook, and chum salmon preferentially spawn in upwelling groundwater, whereas coho prefer downwelling groundwater regions. Groundwater protects fish embryos from freezing during winter incubation and, after hatching, ice-free groundwater allows salmon to move both down and laterally into the hyporheic zone to absorb yolk sacs. Groundwater provides overwintering juvenile fish, such as rearing coho and Chinook salmon, refuge from ice and predators. Groundwater represents a valuable resource that influences salmon spawning behavior, incubation success, extent of overwintering habitat, and biodiversity, all of which can influence salmon sustainability. Recently, over 2,000 km2 of mine claims were staked in headwaters of the Nushagak and Kvichak river watersheds, which produce about 40% of all Bristol Bay sockeye salmon (1956-2010). The Pebble prospect, a 10.8 billion ton, low grade, potentially acid generating, copper deposit is located on the watershed divide of these rivers and represents mine claims closest to permitting. To assess groundwater prevalence and its relationship to salmon resources on mine claims, rivers within claims were surveyed for open ice-free water, 11 March 2011; open water was assumed indicative of groundwater upwelling.