The Impact of Colorism on Historically Black Fraternities and Sororities

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

EAF Annual Report

ALPHA KAPPA ALPHA EDUCATIONAL ADVANCEMENT FOUNDATION, INC. EBRATING 2019 EL C IMPACT REPORT years OF LIFELONG LEARNING Table of Contents President’s Message 40 years P3 Programs P4 Our Mission The mission of the Alpha Kappa Alpha Awards Education Advancement Foundation, Inc.® is to P17 promote lifelong learning. This is accomplished by securing charitable contributions, gifts Financials and endowed funds to award scholarships, P18 fellowships and grants. Leadership P21 Our Vision Donors The Education Advancement Foundation (EAF) sees the consistent P24 and ever-present gap in funding for STEM, music, the arts, youth enrichment and other critical development activities that are vital to supporting our youth and developing well-rounded individuals. We use our dollars to help college students to complete their education, as seed money for charitable endeavors and to support and expand community service projects. Through our mission, our vision is to perpetually reaffirm our commitment of the financial support of educational endeavors. 2 President’s Message While a 40th anniversary is a time for celebration, we are equally mindful of the challenges ahead. With social distancing the new normal at this time, it is clear the world of higher education may never be the same. Nonetheless, 2019 was a very positive year for the Alpha Kappa Alpha Educational Advancement Foundation, Inc.®, and our activities persevere in support of deserving students and organizations — even from today’s virtual world. One thing is clear: when uncertainty reigns in the world, education is the anecdote. Specifically, years higher education that builds critical thinking, communication skills, and robust STEM knowledge years among today’s young scholars — what AKA-EAF defines as excellence. -

Phi Gamma Delta Digital Repository

THE PHI GAMMA DELTA VOL. 135 NO. 2 SPRING 2014 Our Literary Heritage p. 36 TheThe PHI PHI GAMMAGAMMA DELTADELTA Spring 2014 Volume 135, Number 2 Editor William A. Martin III (Mississippi State 1975) [email protected] Director of Communications Melanie K. Musick [email protected] Circulation 27,229 176,563 men have been initiated into the Fraternity of Phi Gamma Delta since 1848. Founded at Jefferson College, Canonsburg, Pennsylvania, on May 1, 1848, by John Templeton McCarty, Samuel Beatty Wilson, James Elliott, Ellis Bailey Gregg, Daniel Webster Crofts, and Naaman Fletcher. Phi Gamma Delta Web site www.phigam.org For all the latest information, updates, and anything you need to know about Phi Gamma Delta. Change of Address Send any address changes to the International Headquarters by email to [email protected], by phone at (859) 255-1848, by fax at (859) 253-0779 or by mail to P.O. Box 4599, Lexington, KY 40504-4599. At Right Brothers of the Tau Nu Chapter at Rensselaer Polytechnic Institute (RPI) in Troy, New York, stand in front of the church that the house corporation recently purchased and will convert into a chapter house. OnOn thethe CoverCover One of the bookshelves in the Library/Boardroom of Phi Gamma Delta’s International Headquarters. The Phi Gamma Delta is published by The Fraternity of Phi Gamma Delta, 1201 Red Mile Road, P. O. Box 4599, Lexington, KY 40544-4599, (859) 255-1848. POSTMASTER: Send address changes to: The Fraternity of Phi Gamma Delta P. O. Box 4599, Lexington, KY, 40544-4599. Publications Mail Agreement No. -

2019 Order of Omega Greek Awards

2019 Year Order of Omega Greek Awards Ceremony President’s Cup: PHC Chi Omega President’s Cup: IFC Sigma Phi Epsilon President’s Cup: NPHC Zeta Phi Beta Sorority, Inc. Outstanding Social Media: IFC Alpha Tau Omega Outstanding Social Media: PHC Chi Omega Outstanding Social Media: NPHC Alpha Kappa Alpha Sorority, Inc. Outstanding Philanthropic Event: PHC 15k in a Day (Delta Delta Delta) Outstanding Philanthropic Event: IFC Paul Cressy Crawfish Boil (ΚΣ, ΚΑ, ΣΑΕ) Outstanding Philanthropic Event: NPHC Who’s Trying To Get Close (Phi Beta Sigma Fraternity, Inc.) Outstanding Philanthropist: PHC Eleanor Koonce (Pi Beta Phi) Outstanding Philanthropist: NPHC Lauren Bagneris (Alpha Kappa Alpha Sorority, Inc.) Outstanding Philanthropist: IFC Gray Cressy (Kappa Alpha Order) Outstanding Chapter Event: PHC Confidence Day (Kappa Delta) Outstanding Chapter Event: IFC Alumni Networking Event (Sigma Phi Epsilon) Outstanding Chapter Event: NPHC Scholarship Pageant (Phi Beta Sigma Fraternity, Inc.) Outstanding Sisterhood: PHC Alpha Delta Pi Outstanding Brotherhood: IFC Sigma Nu Outstanding Brotherhood: NPHC Phi Beta Sigma Fraternity, Inc. Outstanding New Member: PHC Ellie Santa Cruz (Delta Zeta) Outstanding New Member: IFC Rahul Wahi (Alpha Tau Omega) Outstanding New Member: NPHC Sam Rhodes (Phi Beta Sigma Fraternity, Inc.) Outstanding Chapter Advisor: PHC Kathy Davis (Delta Delta Delta) Outstanding Chapter Advisor: IFC Jay Montalbano (Kappa Alpha Order) Outstanding Chapter Advisor: NPHC John Lewis (Phi Beta Sigma Fraternity, Inc.) Outstanding Sorority House -

Evaluating Historically White Fraternities Through Critical Race Theory

The Vermont Connection Volume 41 Embracing the Whole: Sentience and Interconnectedness in Higher Education Article 15 April 2020 The Space They Take: Evaluating Historically White Fraternities through Critical Race Theory Fonda M. Heenehan The University of Vermont Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.uvm.edu/tvc Part of the Higher Education Commons Recommended Citation Heenehan, Fonda M. (2020) "The Space They Take: Evaluating Historically White Fraternities through Critical Race Theory," The Vermont Connection: Vol. 41 , Article 15. Available at: https://scholarworks.uvm.edu/tvc/vol41/iss1/15 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the College of Education and Social Services at ScholarWorks @ UVM. It has been accepted for inclusion in The Vermont Connection by an authorized editor of ScholarWorks @ UVM. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Heenehan • 115 The Space They Take: Evaluating Historically White Fraternities through Critical Race Theory Fonda Marguerite Heenehan Fraternities and sororities are not often thought of as the starting points for social justice education, especially not historically White fraternities and sororities. In this paper, I outline the missions and values of a select group of historically White fraternities to better understand the foundation from which they are starting their organization. I give an overview of Critical Race Theory (CRT) that gives context for how critical race theory can work in higher education. I conclude with recommendations for reworking his- torically White fraternities with a CRT lens; recommendations are written for national organizations and students, and then for professional staff working with fraternities and sororities, especially historically White fraternities. -

Greek Houses

2 Greek houses Σ Δ Σ Σ Ζ ΚΑ Υ Α 33rd Street Θ Τ ΛΧΑ Δ ΝΜ ΤΕΦ ΑΦ Ξ Α Fresh Τ Grocer Radian Hill ΚΑΘ ΖΨ Walnut Street Walnut Street 34th Street ΣΦΕ Du Bois GSE Street 37th 39th Street Annenberg Van Pelt Α Rotunda ΠΚΦ ∆ Movie Huntsman Π Hillel ΑΧΡ theater Rodin ΔΦ SP2 Woodland Walk Locust Walk ΑΤΩ ΣΧ Locust Walk ΔΨ ΦΓΔ 3609-11 36th Street Fisher Class of 1920 Commons ΚΣ Φ Fine 38th Street 40th Street Δ Harnwell Steinberg- Arts McNeil Θ Deitrich ΨΥ College Hall Cohen Harrison ΖΒΤ Houston Irvine Van Pelt Σ Α Β Wistar Williams Α Χ Θ Allegro 41st Street 41st Spruce Street Ε Ω Π Spruce Street Δ Φ The Quad Δ Κ Stouffer ΔΚΕ Δ Ψ Σ Χ ΠΠ Κ Ω Κ Λ HUP N ΑΦ Vet school Pine Street Chapter Letters Address Page Chapter Letters Address Page Chapter Letters Address Page Alpha Chi Omega* ΑΧΩ 3906 Spruce St. 9 Kappa Alpha Society ΚΑ 124 S. 39th St. 15 Sigma Alpha Mu ΣΑΜ 3817 Walnut St. 17 Alpha Chi Rho ΑΧΡ 219 S. 36th St. 7 Kappa Alpha Theta* ΚΑΘ 130 S. 39th St. 15 Sigma Chi ΣΧ 3809 Locust Walk 3 Alpha Delta Pi* ADP 4032 Walnut St. 14 Kappa Sigma ΚΣ 3706 Locust Walk 4 Sigma Delta Tau* ΣΔΤ 3831-33 Walnut St. 16 Alpha Phi* ΑΦ 4045 Walnut St. 14 Lambda Chi Alpha ΛΧΑ 128 S. 39th St. 15 Sigma Kappa* ΣΚ 3928 Spruce St. 11 Alpha Tau Omega ΑΤΩ 225 S. 39th St. -

Through Our Mission, Our Vision Is to Perpetually Reaffirm Our Commitment to the Financial Support of Educational Endeavors

OurOur VisionVision The Educational Advancement Foundation®sees the consistent and ever-present gap in funding for STEM, music, the arts, youth enrichment and other critical development activities that are vital to supporting our youth and developing well-rounded individuals. We use our dollars to help college students to complete their education, as seed money for charitable endeavors and to support and expand community service projects. Through our mission, our vision is to perpetually reaffirm our commitment to the financial support of educational endeavors. EXEMPLIFYING EXCELLENCE Through EAF® President’s Message It gives me great pleasure to present this year’s annual report of activities of the Alpha Kappa Alpha Educational Advancement Foundation®, Incorporated. While it’s been another successful year focused on supporting hundreds of college students with the rising costs of obtaining a college or advanced degree, it has also been a year of organizational change. As of July 2018, the Foundation experienced a change in leadership with the election of a new Board of Directors and the appointment of 10 new Regional Coordinators who are responsible for sharing the mission of the Foundation across our sorority’s footprint and in our communities. Our new theme for the next four years is “Exemplifying Excellence Through EAF®.” “ lpha Under this theme we will renew our commitment to promoting lifelong learning by supporting students pursuing their higher educational goals and KappaA Alpha’s 111- providing grants to community organizations whose projects address one of the programmatic thrusts of Alpha Kappa Alpha Sorority, Incorporated. year history is deeply interwoven into the I announced in August 2018 that EAF® would partner with Alpha Kappa Alpha Sorority to execute and implement an AKA HBCU Endowment Initiative. -

KOREY MICHAEL WASHINGTON Production Designer Cardioid-Oval-2Wz6.Squarespace.Com

KOREY MICHAEL WASHINGTON Production Designer cardioid-oval-2wz6.squarespace.com PROJECTS Partial List DIRECTORS PRODUCERS/STUDIOS THE WONDER YEARS Fred Savage 20TH TELEVISION / ABC Pilot Melissa Wylie, Saladin Patterson ALL AMERICAN Pilot & Series Various Directors WARNER BROS. / THE CW Art Director Lori-Etta Taub, Nkechi Okoro Carroll AMBITIONS Benny Boom OWN / WILL PACKER PROD. Pilot & Series Various Directors Dianne Ashford, Jamey Giddens, Will Packer HART OF THE CITY Leslie Small COMEDY CENTRAL Season 2 Kevin Hart, Dana Riddick, Joey Wells HOUSE OF PAYNE Tyler Perry TBS Seasons 6 & 7 Various Directors Roger Bobb, Ozzie Areu, Tyler Perry MILES AHEAD Feature Film Don Cheadle SONY PICTURES CLASSICS Art Director Daniel Wagner, Robert Ogden Barnum BELLE’S Ed Weinberger TV ONE Pilot & Series Suny B. Parker Ed Weinberger, Leo Lawrence TEEN WOLF Jeff Davis MTV Pilot Marty Adelstein RECTIFY Seasons 3 & 4 Stephen Gyllenhaal SUNDANCE CHANNEL Art Director Various Directors Marshall Persinger, Mark Johnson STOMP THE YARD 2: HOMECOMING Rob Hardy SCREEN GEMS Feature Film Dianne Ashford, Will Packer THINK LIKE A MAN Feature Film Tim Story SCREEN GEMS 2nd Unit Glenn Gainor, Will Packer, Rob Hardy DROP DEAD DIVA Seasons 1 - 3 Jamie Babbit LIFETIME Art Director Various Directors Robert J. Wilson, Josh Berman THE LENA BAKER STORY Ralph Wilcox AMERICAN WORLD PICTURES Feature Film Ralph Wilcox, Dennis Johnson PASTOR BROWN Rockmond Dunbar ARC ENTERTAINMENT Feature Film Charles Oakley, Shaun Livingston THREE CAN PLAY THAT GAME Samad Davis SONY PICTURES Feature Film Dianne Ashford, Will Packer, Rob Hardy TROIS: THE ESCORT Sylvain White COLUMBIA TRISTAR Feature Film Dianne Ashford, Rob Hardy, Will Packer PANDORA’S BOX Rob Hardy COLUMBIA TRISTAR Feature Film Will Packer, Gregory Anderson SPECIALS Partial List UNT MS. -

Timeline of Fraternities and Sororities at Texas Tech

Timeline of Fraternities and Sororities at Texas Tech 1923 • On February 10th, Texas Technological College was founded. 1924 • On June 27th, the Board of Directors voted not to allow Greek-lettered organizations on campus. 1925 • Texas Technological College opened its doors. The college consisted of six buildings, and 914 students enrolled. 1926 • Las Chaparritas was the first women’s club on campus and functioned to unite girls of a common interest through association and engaging in social activities. • Sans Souci – another women’s social club – was founded. 1927 • The first master’s degree was offered at Texas Technological College. 1928 • On November 21st, the College Club was founded. 1929 • The Centaur Club was founded and was the first Men’s social club on the campus whose members were all college students. • In October, The Silver Key Fraternity was organized. • In October, the Wranglers fraternity was founded. 1930 • The “Matador Song” was adopted as the school song. • Student organizations had risen to 54 in number – about 1 for every 37 students. o There were three categories of student organizations: . Devoted to academic pursuits, and/or achievements, and career development • Ex. Aggie Club, Pre-Med, and Engineering Club . Special interest organizations • Ex. Debate Club and the East Texas Club . Social Clubs • Las Camaradas was organized. • In the spring, Las Vivarachas club was organized. • On March 2nd, DFD was founded at Texas Technological College. It was the only social organization on the campus with a name and meaning known only to its members. • On March 3rd, The Inter-Club Council was founded, which ultimately divided into the Men’s Inter-Club Council and the Women’s Inter-Club Council. -

A Guide for College & University

PBS-5b | MEMBER 2020 ACKNOWLEDGEMENT OF ANTI-HAZING PHI BETA SIGMAPOLICY FRATERNITY, AND INC. HOLD HARMLESS AGREEMENT A GUIDE FOR COLLEGE UPDATED: 11/8/2017 & UNIVERSITY OFFICIALS 145 KENNEDY STREET, NW | WASHINGTON, D.C. 20011 www.phibetasigma1914.org www.phibetasigma1914.org TABLE OF CONTENT Message from the President pg3 About Phi Beta Sigma Fraternity, Inc. pg4 Phi Beta Sigma’s Community Initiatives, Partnerships and Programs pg5 Training, Development and Support pg6 Fraternity Structure pg7 Organizational Flow pg9 Membership Criteria pg10 2 Sigma’s MIP at a glance pg11 Sigma’s Risk Management Policy pg14 2018 Regional Conference Schedule pg49 2017 Fraternity Highlights pg50 Notable Members pg52 Phi Beta Sigma’s Branding Standards pg55 MESSAGE FROM THE PRESIDENT Dear Campus Partner- It is an honor and a privilege to address you as the 35th International President of Phi Beta Sigma Fraternity, Incorporated! This is an exciting time to be a Sigma, as our Fraternity moves into a new era, as “A Brotherhood of Conscious Men Actively Serving Our Communities.” We are excited about the possibilities of having an even greater impact on your campus as the Men of Sigma march on! We prepared this booklet to provide you a glance into the world of Phi Beta Sigma, our cause and our initiatives. Indeed, we are a brotherhood of conscious men; Conscious Husbands, Conscious Fathers, Conscious Servants, Conscious Leaders, called to improve the lives of the people we touch. Our collegiate Brothers play a major role in achieving our mission, as they are the lifeblood and future of our Fraternity and communities. -

26/21/5 Alumni Association Alumni Archives National Fraternity Publications

26/21/5 Alumni Association Alumni Archives National Fraternity Publications ACACIA Acacia Fraternity: The Third Quarter Century (1981) Acacia Sings (1958) First Half Century (1954) Pythagoras: Pledge Manual (1940, 1964, 1967, 1971) Success Through Habit, Long Range Planning Program (1984-1985) ** The Acacia Fraternity. Pythagoras: A Manual for the Pledges of Acacia. Fulton, Missouri: Ovid Bell Press, 1940. The Acacia Fraternity. Pythagoras: A Manual for the Pledges of Acacia. Fulton, Missouri: Ovid Bell Press, 1945. The Acacia Fraternity. Pythagoras: A Manual for the Pledges of Acacia. Prairie du Chien, Wisconsin: Howe Printing Company, 1948. The Acacia Fraternity. Pythagoras: Pledge Manual of the Acacia Fraternity. Nashville, Tennessee: Benson Printing Company, 1964 The Acacia Fraternity. Pythagoras: Pledge Manual of the Acacia Fraternity. Nashville, Tennessee: Benson Printing Company, 1967. 9th edition(?). No author. Pythagoras: Membership Manual of the Acacia Fraternity. Boulder, Colorado: Acacia Fraternity National Headquarters, 1971(?). 10th edition. Ed. Snapp, R. Earl. Acacia Sings. Evanston, Illinois: Acacia Fraternity, 1958. Goode, Delmer. Acacia Fraternity: The Third Quarter Century. No Location: Acacia Fraternity, 1981. Dye, William S. Acacia Fraternity: The First Half Century. Nashville, Tennessee: Benson Printing Company, 1954. No Author. Success Through Habits: The Long-Range Planning Program of Acacia Fraternity, 1984-85. Kansas City, MO: National Council Summer Meeting, 1984. 26/21/5 2 AAG Association of Women in Architecture -

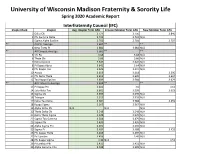

Spring 2020 Community Grade Report

University of Wisconsin Madison Fraternity & Sorority Life Spring 2020 Academic Report Interfraternity Council (IFC) Chapter Rank Chapter Avg. Chapter Term GPA Initiated Member Term GPA New Member Term GPA 1 Delta Chi 3.777 3.756 3.846 2 Phi Gamma Delta 3.732 3.732 N/A 3 Sigma Alpha Epsilon 3.703 3.704 3.707 ** All FSL Average 3.687 ** ** 4 Beta Theta Pi 3.681 3.682 N/A ** All Campus Average 3.681 ** ** 5 Chi Psi 3.68 3.68 N/A 6 Theta Chi 3.66 3.66 N/A 7 Delta Upsilon 3.647 3.647 N/A 8 Pi Kappa Alpha 3.642 3.64 N/A 9 Phi Kappa Tau 3.629 3.637 N/A 10 Acacia 3.613 3.618 3.596 11 Phi Delta Theta 3.612 3.609 3.624 12 Tau Kappa Epsilon 3.609 3.584 3.679 ** All Fraternity Average 3.604 ** ** 13 Pi Kappa Phi 3.601 3.6 3.61 14 Zeta Beta Tau 3.601 3.599 3.623 15 Sigma Chi 3.599 3.599 N/A 16 Triangle 3.593 3.593 N/A 17 Delta Tau Delta 3.581 3.588 3.459 18 Kappa Sigma 3.567 3.567 N/A 19 Alpha Delta Phi N/A N/A N/A 20 Theta Delta Chi 3.548 3.548 N/A 21 Delta Theta Sigma 3.528 3.529 N/A 22 Sigma Tau Gamma 3.504 3.479 N/A 23 Sigma Phi 3.495 3.495 N/A 24 Alpha Sigma Phi 3.492 3.492 N/A 25 Sigma Pi 3.484 3.488 3.452 26 Phi Kappa Theta 3.468 3.469 N/A 27 Psi Upsilon 3.456 3.49 N/A 28 Phi Kappa Sigma 3.44 N/A 3.51 29 Pi Lambda Phi 3.431 3.431 N/A 30 Alpha Gamma Rho 3.408 3.389 N/A Multicultural Greek Council (MGC) Chapter Rank Chapter Chapter Term GPA Initiated Member Term GPA New Member Term GPA 1 Lambda Theta Alpha Latin Sorority, Inc. -

In Association with the Flynn Center Present

Spruce Peak Arts In Association with the Flynn Center Present Step Afrika! Welcome to the 2018-2019 Student Matinee Season! Today’s scholars and researchers say creativity is the top skill our kids will need when they enter the workforce of the future, so we salute YOU for valuing the educational and inspirational power of live performance. By using this study guide you are taking an even greater step toward implementing the arts as a vital and inspiring educational tool. We hope you find this guide useful and that it deepens your students’ connection to the material. If we can help in any way, please contact [email protected]. Enjoy the show! -Education Staff An immense thank you... Performances at Spruce Peak are supported by the Spruce Peak Arts Community & Education Fund, THe Arnold G. and Martha M. Langbo Foundation, the Lintilhac Foundation, the George W. Mergens Foundation, and the Windham Foundation. Additional funding from the SPruce PEak Lights Festival Sponsors: the Baird Family, Jill Boardman and Family, David Clancy, Dawn & Kevin D’Arcy, the DeStefano Family, the Laquerre-Franklin Family, the Gaines Family, the Green Family, Lauren & Jack Handrahan, Kristi & Evan Lovell, Heather & Bill Maffie, the Ohler Family, Sebastien Paradis, the Patch Family, the Rhinesmith Family, Grand Slam Tennis Tour, Carlos & Allison Serrano-Zevallos, Tyler Savage, Patti Martin Spence, Sidney Stark, Nancy & Bill Steers, and Ken Taylor. Thank you to the Flynn Matinee 2018-2019 underwriters: Northfield Savings Bank, Champlain Investment Partners, LLC, Bari and Peter Dreissigacker, Everybody Belongs at the Flynn Fund, Ford Foundation, Forrest and Frances Lattner Foundation, Surdna Foundation, TD Charitable Foundation, Vermont Arts Council, Everybody Belongs Arts Initiative of Burlington Town Center/Devonwood, Vermont Community Foundation, New England Foundation for the Arts, National Endowment for the Arts.