Fiscal Disparities and the Equalization Effects of Fiscal Transfers at The

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

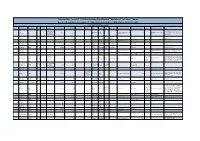

RELACION DE LUGARES DE PRODUCCION AUTORIZADOS a EXPORTAR PERAS (Pyrus Bretschneider, Pyrus Pyrifolia, Pyrus Sp. Nr Communis) AL PERU

RELACION DE LUGARES DE PRODUCCION AUTORIZADOS A EXPORTAR PERAS (Pyrus bretschneider, Pyrus pyrifolia, Pyrus sp. Nr communis) AL PERU 2019-2020年中国鲜梨输往秘鲁注册果园名单 LIST OF REGISTERED ORCHARDS FOR FRESH PEARS EXPORTING TO PURE IN THE YEAR OF 2019-2020 序号 所在地中文名 果园中文名称 所在地英文名 果园英文名称 中文地址 英文地址 注册登记号 No. Location Orchard Name Location (English) Orchard Name (English) Address (Chinese) Address (English) Registered Code (Chinese) (Chinese) ZHANGMINGFU VILLAGE, 1 河北辛集 XINJI,HEBEI 裕隆果园 YULONG ORCHARD 河北省辛集市张名府村 1300GY002 XINJI CITY, HEBEI LVJIAZHUANG, MAYU 2 河北晋州 JINZHOU,HEBEI 吕家庄果园 LVJIAZHUANG ORCHARD 河北省晋州市马于镇吕家庄村 TOWN,JINZHOU CITY, 1300GY007 HEBEI BEINIEPAN,ZHOUJIAZHUAN ZHOUJIAZHUANG SHIDUI 河北省晋州市周家庄乡北捏盘 3 河北晋州 JINZHOU,HEBEI 周家庄十队果园 G TOWN, JINZHOU CITY, 1300GY008 ORCHARD 村 HEBEI DUANJIAZHUANG, JINZHOU 4 河北晋州 JINZHOU,HEBEI 段家庄果园 DUANJIAZHUANG ORCHARD 河北省晋州市段家庄村 1300GY009 CITY, HEBEI ZHOUJIAZHUANG, JINZHOU 5 河北晋州 JINZHOU,HEBEI 周家庄果园 ZHOUJIAZHUANG ORCHARD 河北省晋州市周家庄 1300GY012 CITY, HEBEI LUGUO VILLAGE, XINJI 6 河北辛集 XINJI,HEBEI 裕隆路过果园 YULONG LUGUO ORCHARD 河北省辛集市路过村 1300GY016 CITY, HEBEI ZHOUJIAZHUANG QIDUI ZHOUJIAZHUANG, JINZHOU 7 河北晋州 JINZHOU,HEBEI 周家庄七队果园 河北省晋州市周家庄 1300GY030 ORCHARD CITY, HEBEI MAZHUANG VILLAGE, XINJI 8 河北辛集 XINJI,HEBEI 马庄果园 MAZHUANG ORCHARD 河北省辛集市马庄村 1300GY052 CITY, HEBEI JINMAJU 9 河北泊头 BOTOU,HEBEI 金马果园 JINMA ORCHARD 泊头市王武镇金马驹村 VILLAGE,WANGWU TOWN, 1306GY001 BOTOU CITY CUIQIAO VILLAGE, 10 河北泊头 BOTOU,HEBEI 金业果园 JINYE ORCHARD 泊头市西辛店镇崔桥村 XIXINDIAN TOWN, BOTOU 1306GY003 CITY RELACION DE LUGARES DE PRODUCCION AUTORIZADOS A EXPORTAR PERAS -

Evaluation of the Development of Rural Inclusive Finance: a Case Study of Baoding, Hebei Province

2018 4th International Conference on Economics, Management and Humanities Science(ECOMHS 2018) Evaluation of the Development of Rural Inclusive Finance: A Case Study of Baoding, Hebei province Ziqi Yang1, Xiaoxiao Li1 Hebei Finance University, Baoding, Hebei Province, China Keywords: inclusive finance; evaluation; rural inclusive finance; IFI index method Abstract: "Inclusive Finance", means that everyone has financial needs to access high-quality financial services at the right price in a timely and convenient manner with dignity. This paper uses IFI index method to evaluate the development level of rural inclusive finance in various counties of Baoding, Hebei province in 2016, and finds that rural inclusive finance in each country has a low level of development, banks and other financial institutions have few branches and product types, the farmers in that area have conservative financial concepts and rural financial service facilities are not perfect. In response to these problems, it is proposed to increase the development of inclusive finance; encourage financial innovation; establish financial concepts and cultivate financial needs; improve broadband coverage and accelerate the popularization of information. 1. Introduction "Inclusive Finance", means that everyone with financial needs to access high-quality financial services at the right price in a timely and convenient manner with dignity. This paper uses IFI index method to evaluate the development level of rural Inclusive Finance in various counties of Baoding, Hebei province -

Impact of Wheat Harvest on Levels and Sources of PM2.5-Associated

ORIGINAL RESEARCH https://doi.org/10.4209/aaqr.200625 Impact of Wheat Harvest on Levels and Sources of PM2.5-associated PAHs in an Urban Area Located at Aerosol and Air Quality Research the Center of Beijing-Tianjin-Hebei Region Zhiyong Li1,2*, Zhenxin Li1, Ziyuan Yue1, Dingyuan Yang1, Yutong Wang1, 1,2 1 1 3 1 1 Lan Chen , Songtao Guo , Jinsong Yao , Lei Wang , Xiao Lou , Xiaolin Xu , Jinye Wei1, Baole Deng4*, Hong Wu5 1 A Hebei Key Lab of Power Plant Flue Gas Multi-Pollutants Control, Department of Environmental Science and Engineering, North China Electric Power University, Baoding 071003, China 2 MOE Key Laboratory of Resources and Environmental Systems Optimization, Ministry of Education, Beijing 102206, China 3 Hebei Research Center for Geoanalysis, Baoding 071003, China 4 Tianjin Eco-Environmental Monitoring Center, Tianjin 300191, China 5 College of Environment and Resources, Chongqing Technology and Business University, Chongqing 400067, China ABSTRACT Wheat harvest and subsequent straw burning for maize planting can cause severe PM2.5 and PAH pollutions and deteriorate the air quality of nearby cities in consequence. PM2.5 samples were collected in Baoding urban area (BUA) from June 18 to July 7 of 2019, during and after wheat harvest (DWH and AWH, respectively). The “Migration Effect” (i.e., PM2.5 and PAHs transferred from rural to urban during DWH and AWH, respectively) was proved by both the later time for appearance of peak values of PM2.5 and PAHs and the air mass origins in BUA. The daily OPEN ACCESS –3 average PM2.5 (reported in µg m ) 137 of DWH was 2.58 times 53.1 of AWH for BUA, regardless of its lower levels than the corresponding 156 and 75.6 for an adjacent rural site (ARS). -

Table of Codes for Each Court of Each Level

Table of Codes for Each Court of Each Level Corresponding Type Chinese Court Region Court Name Administrative Name Code Code Area Supreme People’s Court 最高人民法院 最高法 Higher People's Court of 北京市高级人民 Beijing 京 110000 1 Beijing Municipality 法院 Municipality No. 1 Intermediate People's 北京市第一中级 京 01 2 Court of Beijing Municipality 人民法院 Shijingshan Shijingshan District People’s 北京市石景山区 京 0107 110107 District of Beijing 1 Court of Beijing Municipality 人民法院 Municipality Haidian District of Haidian District People’s 北京市海淀区人 京 0108 110108 Beijing 1 Court of Beijing Municipality 民法院 Municipality Mentougou Mentougou District People’s 北京市门头沟区 京 0109 110109 District of Beijing 1 Court of Beijing Municipality 人民法院 Municipality Changping Changping District People’s 北京市昌平区人 京 0114 110114 District of Beijing 1 Court of Beijing Municipality 民法院 Municipality Yanqing County People’s 延庆县人民法院 京 0229 110229 Yanqing County 1 Court No. 2 Intermediate People's 北京市第二中级 京 02 2 Court of Beijing Municipality 人民法院 Dongcheng Dongcheng District People’s 北京市东城区人 京 0101 110101 District of Beijing 1 Court of Beijing Municipality 民法院 Municipality Xicheng District Xicheng District People’s 北京市西城区人 京 0102 110102 of Beijing 1 Court of Beijing Municipality 民法院 Municipality Fengtai District of Fengtai District People’s 北京市丰台区人 京 0106 110106 Beijing 1 Court of Beijing Municipality 民法院 Municipality 1 Fangshan District Fangshan District People’s 北京市房山区人 京 0111 110111 of Beijing 1 Court of Beijing Municipality 民法院 Municipality Daxing District of Daxing District People’s 北京市大兴区人 京 0115 -

The Chinese State in Ming Society

The Chinese State in Ming Society The Ming dynasty (1368–1644), a period of commercial expansion and cultural innovation, fashioned the relationship between the present-day state and society in China. In this unique collection of reworked and illustrated essays, one of the leading scholars of Chinese history re-examines this relationship and argues that, contrary to previous scholarship, which emphasized the heavy hand of the state, it was radical responses within society to changes in commercial relations and social networks that led to a stable but dynamic “constitution” during the Ming dynasty. This imaginative reconsideration of existing scholarship also includes two essays first published here and a substantial introduction, and will be fascinating reading for scholars and students interested in China’s development. Timothy Book is Principal of St. John’s College, University of British Colombia. Critical Asian Scholarship Edited by Mark Selden, Binghamton and Cornell Universities, USA The series is intended to showcase the most important individual contributions to scholarship in Asian Studies. Each of the volumes presents a leading Asian scholar addressing themes that are central to his or her most significant and lasting contribution to Asian studies. The series is committed to the rich variety of research and writing on Asia, and is not restricted to any particular discipline, theoretical approach or geographical expertise. Southeast Asia A testament George McT.Kahin Women and the Family in Chinese History Patricia Buckley Ebrey -

Mapping the Distribution of Water Resource Security in the Beijing-Tianjin-Hebei Region at the County Level Under a Changing Context

sustainability Article Mapping the Distribution of Water Resource Security in the Beijing-Tianjin-Hebei Region at the County Level under a Changing Context 1,2,3, 4, 1, 3,5, 1,6 Xiang Li y, Dongqin Yin y, Xuejun Zhang *, Barry F.W. Croke *, Danhong Guo , Jiahong Liu 1 , Anthony J. Jakeman 3 , Ruirui Zhu 3, Li Zhang 2, Xiangpeng Mu 1, Fengran Xu 1 and Qian Wang 3,7 1 State Key Laboratory of Simulation and Regulation of Water Cycle in River Basin, China Institute of Water Resources and Hydropower Research, Beijing 100038, China; [email protected] (X.L.); [email protected] (D.G.); [email protected] (J.L.); [email protected] (X.M.); [email protected] (F.X.) 2 State Key Laboratory of Plateau Ecology and Agriculture, Qinghai University, Xining 810000, China; [email protected] 3 Fenner School of Environment and Society, Australian National University, Canberra 2601, Australia; [email protected] (A.J.J.); [email protected] (R.Z.); [email protected] (Q.W.) 4 College of Land Science and Technology, China Agricultural University, Beijing 100000, China; [email protected] 5 Mathematical Sciences Institute, Australian National University, Canberra 2601, Australia 6 School of Hydraulic Engineering, Changsha University of Science & Technology, Changsha 410000, China 7 State Key Laboratory of Hydrology-Water Resources and Hydraulic Engineering, Center for Global Change and Water Cycle, Hohai University, Nanjing 210000, China * Correspondence: [email protected] (X.Z.); [email protected] (B.F.W.C.) These authors contributed equally to this work. y Received: 8 October 2019; Accepted: 12 November 2019; Published: 16 November 2019 Abstract: The Beijing-Tianjin-Hebei (Jingjinji) region is the most densely populated region in China and suffers from severe water resource shortage, with considerable water-related issues emerging under a changing context such as construction of water diversion projects (WDP), regional synergistic development, and climate change. -

Make a Living: Agriculture, Industry and Commerce in Eastern Hebei, 1870-1937 Fuming Wang Iowa State University

Iowa State University Capstones, Theses and Retrospective Theses and Dissertations Dissertations 1998 Make a living: agriculture, industry and commerce in Eastern Hebei, 1870-1937 Fuming Wang Iowa State University Follow this and additional works at: https://lib.dr.iastate.edu/rtd Part of the Agriculture Commons, Asian History Commons, Economic History Commons, and the Other History Commons Recommended Citation Wang, Fuming, "Make a living: agriculture, industry and commerce in Eastern Hebei, 1870-1937 " (1998). Retrospective Theses and Dissertations. 11819. https://lib.dr.iastate.edu/rtd/11819 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Iowa State University Capstones, Theses and Dissertations at Iowa State University Digital Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Retrospective Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Iowa State University Digital Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. INFORMATION TO USERS This manuscript has been reproduced from the microfilm master. UMI films the text directly fi'om the original or copy submitted. Thus, some thesis and dissertation copies are in typewriter &c&, while others may be fi-om any type of computer printer. The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. Broken or indistinct print, colored or poor quality illustrations and photographs, print bleedthrough, substandard margins, and improper alignment can adversely afiect reproduction. In the unlikely event that the author did not send UMI a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if unauthorized copyright material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. -

Documented Cases of 1,352 Falun Gong Practitioners "Sentenced" to Prison Camps

Documented Cases of 1,352 Falun Gong Practitioners "Sentenced" to Prison Camps Based on Reports Received January - December 2009, Listed in Descending Order by Sentence Length Falun Dafa Information Center Case # Name (Pinyin)2 Name (Chinese) Age Gender Occupation Date of Detention Date of Sentencing Sentence length Charges City Province Court Judge's name Place currently detained Scheduled date of release Lawyer Initial place of detention Notes Employee of No.8 Arrested with his wife at his mother-in-law's Mine of the Coal Pingdingshan Henan Zhengzhou Prison in Xinmi City, Pingdingshan City Detention 1 Liu Gang 刘刚 m 18-May-08 early 2009 18 2027 home; transferred to current prison around Corporation of City Province Henan Province Center March 18, 2009 Pingdingshan City Nong'an Nong'an 2 Wei Cheng 魏成 37 m 27-Sep-07 27-Mar-09 18 Jilin Province County Guo Qingxi March, 2027 Arrested from home; County Court Zhejiang Fuyang Zhejiang Province Women's 3 Jin Meihua 金美华 47 f 19-Nov-08 15 Fuyang City November, 2023 Province City Court Prison Nong'an Nong'an 4 Han Xixiang 韩希祥 42 m Sep-07 27-Mar-09 14 Jilin Province County Guo Qingxi March, 2023 Arrested from home; County Court Nong'an Nong'an 5 Li Fengming 李凤明 45 m 27-Sep-07 27-Mar-09 14 Jilin Province County Guo Qingxi March, 2023 Arrested from home; County Court Arrested from home; detained until late April Liaoning Liaoning Province Women's Fushun Nangou Detention 6 Qi Huishu 齐会书 f 24-May-08 Apr-09 14 Fushun City 2023 2009, and then sentenced in secret and Province Prison Center transferred to current prison. -

RC1: This Paper Applied the WRF-CMAQ Model to Simulate The

RC1: This paper applied the WRF-CMAQ model to simulate the air quality over the Beijing- Tianjin-Hebei area and calculate the trans-boundary fluxes to Beijing, Tianjin, and Shijiazhuang. This paper used a new method that assessed the pollutants transport by vertical surface flux calculation instead of usually used scenario analysis. Author’s reply: We feel encouraged to receive the reviewer’s recognition for our work. We treasure the valuable comments raised by the referee and have followed them in revising the manuscript. Please check the below for the point-to-point responses. (1) Using this method, it is easily to understand the pollutants inflows from each direction or each surrounding city to the objective city. But the inflows from one city didn’t necessarily mean those pollutants were from that city. It might be generated from the upflow cities. Did the authors consider about that? And is there any consideration about solving this? Authors’ reply: We appreciate for the valuable comment. Indeed, the transport flux itself could not tell whether the pollutants are from the neighbor city or from other upstream cities, and this problem is one of the major disadvantages of the flux method. However, the goal of using the flux method is mainly focused on the transport from different directions, rather than the contribution of different cities. By putting together the transport characteristics of different cities as is done in our study (see Fig. R1), we have obtained a general transport feature in the BTH region, which can facilitate a qualitative understanding of where the fluxes are mainly from. -

Sentencing Cases of Falun Gong Practitioners Reported in January 2021

186 Sentencing Cases of Falun Gong Practitioners Reported in January 2021 Minghui.org Case Prison Probation Year Month Fine / Police Name Province City Court Number Term (yrs) Sentenc Sentenced Extortion #1 黄日新 Huang Rixin Guangdong Dongguan Dongguan City No.2 Court 3 2020 Feb ¥ 30,000 #2 安春云 An Chunyun Tianjin Dagang Court 0.83 2020 Feb ¥ 1,000 #3 王占君 Wang Zhanjun Jilin Changchun Dehui City Court 6 2020 Mar #4 毕业海 Bi Yehai Jilin Changchun Dehui City Court 3 2020 Mar #5 刘兴华 Liu Xinghua Jilin Changchun Dehui City Court 2 2020 Mar #6 张文华 Zhang Wenhua Jilin Changchun Dehui City Court 1.5 2020 Mar #7 何维玲(何维林) He Weiling (He Weilin) Anhui Hefei Shushan District Court 2.83 2020 May #8 马庆霞 Ma Qingxia Tianjin Wuqing District Court 5 2020 Jun #9 陈德春 Chen Dechun Sichuan Chengdu 3 2020 Jun ¥ 2,000 #10 余志红 Yu Zhihong Liaoning Yingkou 1.5 2020 Jul #11 陈星伯 Chen Xingbo Hebei Xingtai Xiangdu District Court 3 2020 Aug #12 肖大富 Xiao Dafu Sichuan Dazhou Tongchuan District Court 8.5 2020 Sep #13 汤艳兰 Tang Yanlan Guangdong Jiangmen Pengjiang District Court 8 2020 Sep ¥ 10,000 #14 李行军 Li Xingjun Hubei Jingzhou 7 2020 Sep #15 孙江怡 Sun Jiangyi Hubei Jingzhou 7 2020 Sep #16 雷云波 Lei Yunbo Hubei Jingzhou 6 2020 Sep #17 陈顺英 Chen Chunying Hubei Jingzhou 3.5 2020 Sep #18 刘瑞莲 Liu Ruilian Hebei Chengde 3 2020 Sep #19 卢丽华 Lu Lihua Jiangsu Nantong Chongchuan Court 1 2020 Sep #20 张海燕 Zhang Haiyan Heilongjiang Harbin 3 3 2020 Sep #21 王亚琴 Wang Yaqin Jilin Jilin 5.5 2020 Oct #22 许凤梅 Xu Fengmei Henan Zhoukou Chuanhui District Court 5 2020 Oct #23 郭远和 Guo Yuanhe Hunan Chenzhou -

Download Article (PDF)

Advances in Economics, Business and Management Research, volume 56 3rd International Conference on Economic and Business Management (FEBM 2018) Study on the Wetland’s Scientific Attributes and Its Restoration in Baiyangdian Lake Zhen Wang, Jisong Wu, Jingyang Xia* School of Economics and Management Beihang University Beijing, China [email protected] Abstract—Through an analysis of the wetland definition with into both the interaction between a wetland ecosystem and its legal effect, this paper gives an elaboration about a scientific surrounding ecosystem, and the response mechanism of the conclusion that the scientific attribute of Baiyangdian Lake, wetland ecosystem at the extreme environment conditions and Xiong’an is wetland rather than lake, and further defines the improved the nature wetland ecological system assessment wetland’s scientific attributes that are different from lake’s. The technology [5]. Liu Xiaoyan, et al. analyzed the changes of the scientific suggestions on wetland ecological restoration in wetland ecological features and did a lot of research on the Baiyangdian Lake are put forward. Finally, the specific realization of sustainable urban development with the measures in and suggestions on ecological governance in ecological restoration project of Qingxi Wetland of Shanghai Baiyangdian are proposed. as the example [6]. Wu Xiaoqin set up methods for eco- Keywords—Baiyangdian Lake; Xiong’an new area; Wetland; environmental evaluation of the estuarine wetlands of Fujian Ecological restoration Province in which the evaluation index system and assignment standard are included [7]. Chen Hong, et al. studied the changes of hydrological environment of Baiyangdian, and I. INTRODUCTION proposed to establish ecological water replenishment Located in center of the North China Plain, Baiyangdian mechanism, comprehensively manage pollution sources, and Lake is the central zone of three counties, which make up set up a security system to promote integrated river basin Xiongan New Area, namely Rongcheng County, Anxin management [8]. -

Minimum Wage Standards in China August 11, 2020

Minimum Wage Standards in China August 11, 2020 Contents Heilongjiang ................................................................................................................................................. 3 Jilin ............................................................................................................................................................... 3 Liaoning ........................................................................................................................................................ 4 Inner Mongolia Autonomous Region ........................................................................................................... 7 Beijing......................................................................................................................................................... 10 Hebei ........................................................................................................................................................... 11 Henan .......................................................................................................................................................... 13 Shandong .................................................................................................................................................... 14 Shanxi ......................................................................................................................................................... 16 Shaanxi ......................................................................................................................................................