C L E V E L a N D a N D T E

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

North York Moors and Cleveland Hills Area Profile: Supporting Documents

National Character 25. North York Moors and Cleveland Hills Area profile: Supporting documents www.gov.uk/natural-england 1 National Character 25. North York Moors and Cleveland Hills Area profile: Supporting documents Introduction National Character Areas map As part of Natural England’s responsibilities as set out in the Natural Environment 1 2 3 White Paper , Biodiversity 2020 and the European Landscape Convention , we are North revising profiles for England’s 159 National Character Areas (NCAs). These are areas East that share similar landscape characteristics, and which follow natural lines in the landscape rather than administrative boundaries, making them a good decision- Yorkshire making framework for the natural environment. & The North Humber NCA profiles are guidance documents which can help communities to inform their West decision-making about the places that they live in and care for. The information they contain will support the planning of conservation initiatives at a landscape East scale, inform the delivery of Nature Improvement Areas and encourage broader Midlands partnership working through Local Nature Partnerships. The profiles will also help West Midlands to inform choices about how land is managed and can change. East of England Each profile includes a description of the natural and cultural features that shape our landscapes, how the landscape has changed over time, the current key London drivers for ongoing change, and a broad analysis of each area’s characteristics and ecosystem services. Statements of Environmental Opportunity (SEOs) are South East suggested, which draw on this integrated information. The SEOs offer guidance South West on the critical issues, which could help to achieve sustainable growth and a more secure environmental future. -

ORTHODONTIC COMMISSIONING INTENTIONS (Final - Sept 2018)

CUMBRIA & NORTH EAST - ORTHODONTIC COMMISSIONING INTENTIONS (Final - Sept 2018) Contract size Contract Size Units of Indicative Name of Contract Lot Required premise(s) locaton for contract Orthodontic Activity patient (UOAs) numbers Durham Central Accessible location(s) within Central Durham (ie Neville's Cross/Elvet/Gilesgate) 14,100 627 Durham North West Accessible location(s) within North West Durham (ie Stanley/Tanfield/Consett North) 8,000 356 Bishop Auckland Accessible location(s) within Bishop Auckland 10,000 444 Darlington Accessible location(s) within the Borough of Darlington 9,000 400 Hartlepool Accessible location(s) within the Borough of Hartlepool 8,500 378 Middlesbrough Accessible location(s) within the Borough of Middlesbrough 10,700 476 Redcar and Cleveland Accessible location(s) within the Borough of Redcar & Cleveland, (ie wards of Dormanstown, West Dyke, Longbeck or 9,600 427 St Germains) Stockton-on-Tees Accessible location(s) within the Borough of Stockton on Tees) 16,300 724 Gateshead Accessible location(s) within the Borough of Gateshead 10,700 476 South Tyneside Accessible location(s) within the Borough of South Tyneside 7,900 351 Sunderland North Minimum of two sites - 1 x accesible location in Washington, and 1 other, ie Castle, Redhill or Southwick wards 9,000 400 Sunderland South Accessible location(s) South of River Wear (City Centre location, ie Millfield, Hendon, St Michael's wards) 16,000 711 Northumberland Central Accessible location(s) within Central Northumberland, ie Ashington. 9,000 400 Northumberland -

Drinking Establishments in TS13 Liverton Mines, Saltburn

Pattinson.co.uk - Tel: 0191 239 3252 drinking establishments in TS13 Single storey A4 public house Two bedroom house adjoining Liverton Mines, Saltburn-by-the-Sea Excellent development potential (STP) North Yorkshire, TS13 4QH Parking for 3-5 vehicles Great roadside position £95,000 (pub +VAT) Freehold title Pattinson.co.uk - Tel: 0191 239 3252 Summary - Property Type: Drinking Establishments - Parking: Allocated Price: £95,000 Description An end-terraced property of the pub, which is a single-storey construction under flat roofing. It is attached to a two-storey house, which is connected both internally and both have their own front doors. The pub main door is located at the centre of the property and leads into, on the right a Public Bar with pool area. To the left of the entrance is a Lounge Bar. Both rooms are connected by the servery, which has a galley style small kitchen in-between both rooms. There are Gents toilets in the Bar with Ladies toilets in the Lounge. Behind the servery are two rooms, one for storage the other being the beer cellar. We are informed that the two-storey house on the end elevation is also part of the property, but is in poor decorative order and is condemned for habitation. It briefly comprises Lounge, Kitchen and Bathroom on the ground floor and has two double bedrooms and a small box room on the first floor of the house only. The property would lend itself to be used for existing use or be developed for alternative use, subject to the required planning permissions. -

Authorised Memorial Masons and Agents

Bereavement Services AUTHORISED MEMORIAL MASONS Register Office Redcar & Cleveland Leisure & Community Heart AND AGENTS Ridley Street, Redcar TS10 1TD Telephone: 01642 444420/21 T The memorial masons on this list have agreed to abide by the Redcar and Cleveland Borough Council Cemetery Rules and Regulations for the following cemeteries: Boosbeck, Brotton, Eston, Guisborough, Loftus, Redcar, Saltburn and Skelton. They have agreed to adhere to the Code of Practice issued by the National Association of Memorial Masons (NAMM) and have complied with all our registration scheme requirements. Funeral Directors and any other person acting as an agent should ensure that their contracted mason is included before processing any memorial application. This list shows those masons and the agents through their masons who are registered to carry out work within our cemeteries. Redcar and Cleveland Borough Council does not recommend individual masons or agents or accept any responsibility for their workmanship. Grave owners are reminded that they own the memorial and are responsible for ensuring it remains in good repair. The Council is currently undertaking memorial safety checks and any memorial found to be unsafe or dangerous would result in the owner being contacted, where possible, and remedial action being taken. ` MEMORIAL MASONS Expiry Date Address Telephone Number Abbey Memorials Ltd 31 December 2021 Rawreth Industrial Estate, Rawreth Lane, Rayleigh, Essex SS6 9RL 01268 782757 Bambridge Brothers 31 December 2021 223 Northgate, Darlington, DL1 -

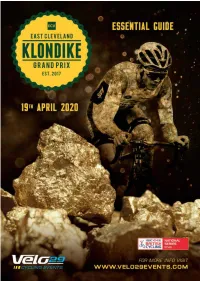

Klondike-Guide.Pdf

YOUR ESSENTIAL GUIDE TO THE KLONDIKE GRAND PRIX Introduction Welcome to the 4th edition of the East Cleveland Grand Prix. The event is brought to you be the East Cleveland Big Local, a lottery funded group to develop the area of East Cleveland and Velo29 Events, a company which hails from Guisborough and specialises in delivering high profile cycle events. The past 3 years have seen the Klondike GP establish itself as one of the most important events in East Cleveland and one of the biggest events in the UK calendar. Certainly it’s the best attend 1 day race in the UK! 2020 is the biggest and most exciting Klondike yet as we’ve not only added some really great free to enjoy family events in Guisborough but also we’ve added an Elite Female race, a huge thing for the event! The entire area will unite and take to the streets to enjoy this wonderful event for the 4th time on the 19th April, don’t miss your place at the road side! We can be sure of an exciting race and a great day out! Richard Williamson – Event Director Velo29 NATIONAL SERIES ROAD The event is run under the rules of British Cycling. The Klondike GP is part of HSBC UK | National Road Series Any enquires to [email protected] Time Table 11:45 Elite Convey assembles on Westgate Guisborough 12:00 Grand Depart Elite Race 12:00 - 15:30 Enjoy the elite racing out in the Villages of East Cleveland 12:15 Youth Racing Guisborough Town Centre 15:30 Youth Racing Finishes 16:00 Elite Finish and Prize giving Westgate Guisborough Where to Watch the Klondike Our top tips for enjoying the Klondike GP. -

Durham E-Theses

Durham E-Theses The development of education in the North Ridings of Yorkshire 1902 - 1939 Jennings, E. How to cite: Jennings, E. (1965) The development of education in the North Ridings of Yorkshire 1902 - 1939, Durham theses, Durham University. Available at Durham E-Theses Online: http://etheses.dur.ac.uk/9965/ Use policy The full-text may be used and/or reproduced, and given to third parties in any format or medium, without prior permission or charge, for personal research or study, educational, or not-for-prot purposes provided that: • a full bibliographic reference is made to the original source • a link is made to the metadata record in Durham E-Theses • the full-text is not changed in any way The full-text must not be sold in any format or medium without the formal permission of the copyright holders. Please consult the full Durham E-Theses policy for further details. Academic Support Oce, Durham University, University Oce, Old Elvet, Durham DH1 3HP e-mail: [email protected] Tel: +44 0191 334 6107 http://etheses.dur.ac.uk Abstract of M. Ed. thesis submitted by B. Jennings entitled "The Development of Education in the North Riding of Yorkshire 1902 - 1939" The aim of this work is to describe the growth of the educational system in a local authority area. The education acts, regulations of the Board and the educational theories of the period are detailed together with their effect on the national system. Local conditions of geograpliy and industry are also described in so far as they affected education in the North Riding of Yorkshire and resulted in the creation of an educational system characteristic of the area. -

Cleveland Naturalists'

CLEVELAND NATURALISTS' FIELD CLUB RECORD OF PROCEEDINGS Volume 5 Part 1 Spring 1991 CONTENTS Recent Sightings and Casual Notes CNFC Recording Events and Workshop Programme 1991 The Forming of a Field Study Group Within the CNFC Additions to Records of Fungi In Cleveland Recent Sightings and Casual Notes CNFC Recording Events and Workshop Programme 1991 The Forming of a Field Study Group Within the CNFC Additions to Records of Fungi In Cleveland CLEVELAND NATURALISTS' FIELD CLUB 111th SESSION 1991-1992 OFFICERS President: Mrs J.M. Williams 11, Kedleston Close Stockton on Tees. Secretary: Mrs J.M. Williams 11 Kedleston Close Stockton on Tees. Programme Secretaries: Misses J.E. Bradbury & N. Pagdin 21, North Close Elwick Hartlepool. Treasurer; Miss M. Gent 42, North Road Stokesley. Committee Members: J. Blackburn K. Houghton M. Yates Records sub-committee: A.Weir, M Birtle P.Wood, D Fryer, J. Blackburn M. Hallam, V. Jones Representatives: I. C.Lawrence (CWT) J. Blackburn (YNU) M. Birtle (NNU) EDITORIAL It is perhaps fitting that, as the Cleveland Naturalist's Field Club enters its 111th year in 1991, we should be celebrating its long history of natural history recording through the re-establishment of the "Proceedings". In the early days of the club this publication formed the focus of information desemmination and was published continuously from 1881 until 1932. Despite the enormous changes in land use which have occurred in the last 60 years, and indeed the change in geographical area brought about by the fairly recent formation of Cleveland County, many of the old records published in the Proceedings still hold true and even those species which have disappeared or contracted in range are of value in providing useful base line data for modern day surveys. -

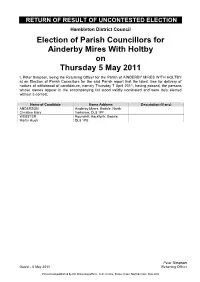

Return of Result of Uncontested Election

RETURN OF RESULT OF UNCONTESTED ELECTION Hambleton District Council Election of Parish Councillors for Ainderby Mires With Holtby on Thursday 5 May 2011 I, Peter Simpson, being the Returning Officer for the Parish of AINDERBY MIRES WITH HOLTBY at an Election of Parish Councillors for the said Parish report that the latest time for delivery of notices of withdrawal of candidature, namely Thursday 7 April 2011, having passed, the persons whose names appear in the accompanying list stood validly nominated and were duly elected without a contest. Name of Candidate Home Address Description (if any) ANDERSON Ainderby Myers, Bedale, North Christine Mary Yorkshire, DL8 1PF WEBSTER Roundhill, Hackforth, Bedale, Martin Hugh DL8 1PB Dated Friday 5 September 2014 Peter Simpson Dated – 5 May 2011 Returning Officer Printed and published by the Returning Officer, Civic Centre, Stone Cross, Northallerton, DL6 2UU RETURN OF RESULT OF UNCONTESTED ELECTION Hambleton District Council Election of Parish Councillors for Aiskew - Aiskew on Thursday 5 May 2011 I, Peter Simpson, being the Returning Officer for the Parish Ward of AISKEW - AISKEW at an Election of Parish Councillors for the said Parish Ward report that the latest time for delivery of notices of withdrawal of candidature, namely Thursday 7 April 2011, having passed, the persons whose names appear in the accompanying list stood validly nominated and were duly elected without a contest. Name of Candidate Home Address Description (if any) LES Forest Lodge, 94 Bedale Road, Carl Anthony Aiskew, Bedale -

Redcar-Cleveland Flyer

SPECIALIST STOP SMOKING SERVICE SESSIONS Redcar & Cleveland 2015 Wednesday Redcar Library 14.30pm - 16.00pm Kirkleatham Street, Redcar TS10 1RT Sunnyfield House Friday Community Centre, Guisborough 13.00pm - 14.30pm TS14 6BA GP PRACTICE STOP SMOKING SUPPORT Stop Smoking Support is also available from many GP practices - to find out if your GP practice provides this support, please contact the Specialist Stop Smoking Service on 01642 383819. No appointment needed for the above Specialist Stop Smoking Sessions. Please note that clients should arrive at least 20 minutes before the stated end times above in order to be assessed. Clinics are subject to changes - to confirm availability please ring the Specialist Stop Smoking Service on 01642 383819. Alternatively, if you have access to the internet, please visit our website S L 5 1 / for up-to-date stop smoking sessions: 3 d e t www.nth.nhs.uk/stopsmoking a d p u Middlesbrough Redcar & Cleveland t Middlesbrough Redcar & Cleveland s Stockton & Hartlepool a Stockton & Hartlepool L PHARMACY ONE STOP SHOPS Redcar & Cleveland Asda Pharmacy *P Coopers Chemist 2 North Street South Bank New Medical Centre Middlesbrough TS6 6AB Coatham Road Redcar TS10 1SR Tel: 01642 443810 Tel: 01642 483861 Boots the Chemist Harrops Chemist High Street Normanby TS6 0NH 1 Zetland Road Loftus TS13 4PP Tel: 01287 640557 Tel: 01642 452777 Lloyds Pharmacy Boots Pharmacy 35 Ennis Road, Rectory Lane Guisborough TS14 7DJ Dormanstown Tel: 01287 632120 TS10 5JZ Tel: 01642 490964 Boots Guisborough Westgate 18 Westgate Guisborough -

Local Wildlife and Geological Sites January 2017

Redcar & Cleveland Local Wildlife and Geological Sites January 2017 this is Redcar & Cleveland 1 BACKGROUND 3 2 SCHEDULE OF LOCAL WILDLIFE SITES 5 3 SCHEDULE OF LOCAL GEOLOGICAL SITES 11 APPENDIX 1: Location Maps 15 2017 y anuar J te Upda Sites Geological and e ildlif W Local Redcar & Cleveland Local Plan 1 2 Local Wildlife and Geological Sites Update January 2017 R edcar & Cle v eland Local Plan 1. BACKGROUND What are Local Sites and why do we need them? 1.1 Local Sites can be Local Wildlife Sites (LWS) or Local Geological Sites (LGS). Local Wildlife Sites are areas of land which meet specific, objective criteria for nature conservation value. These criteria, which are based on the Defra guidance(1), have been decided locally by the Tees Valley Local Sites Partnership. The sites represent a range of important habitat types and variety of species that are of conservation concern. The Tees Valley RIGS (Regionally Important Geological Sites) group advises the Local Sites Partnership on the selection and management of Local Geological Sites, areas which they have identified as being of geological importance. 1.2 Local Sites can provide local contact with nature and opportunities for education, however designation as a Local Site does not confer any right of access. 1.3 Formerly known as Sites of Nature Conservation Interest (SNCIs) and RIGS, Local Sites are non-statutory site designations that have a lower level of protection than statutory designations, such as Sites of Special Scientific Interest (SSSIs). Local Sites, excluding those within the North York Moors National Park, currently receive protection from certain types of inappropriate development through our Local Development Framework. -

ROMANO- BRITISH Villa A

Prehistoric (Stone Age to Iron Age) Corn-Dryer Although the Roman villa had a great impact on the banks The excavated heated room, or of the River Tees, archaeologists found that there had been caldarium (left). activity in the area for thousands of years prior to the Quarry The caldarium was the bath Roman arrival. Seven pots and a bronze punch, or chisel, tell house. Although this building us that people were living and working here at least 4000 was small, it was well built. It years ago. was probably constructed Farm during the early phases of the villa complex. Ingleby Roman For Romans, bath houses were social places where people The Romano-British villa at Quarry Farm has been preserved in could meet. Barwick an area of open space, in the heart of the new Ingleby Barwick housing development. Excavations took place in 2003-04, carried out by Archaeological Services Durham University Outbuildings (ASDU), to record the villa area. This included structures, such as the heated room (shown above right), aisled building (shown below right), and eld enclosures. Caldarium Anglo-Saxon (Heated Room) Winged With the collapse of the Roman Empire, Roman inuence Preserved Area Corridor began to slowly disappear from Britain, but activity at the Structure Villa Complex villa site continued. A substantial amount of pottery has been discovered, as have re-pits which may have been used for cooking, and two possible sunken oored buildings, indicating that people still lived and worked here. Field Enclosures Medieval – Post Medieval Aisled Building Drove Way A scatter of medieval pottery, ridge and furrow earthworks (Villa boundary) Circular Building and early eld boundaries are all that could be found relating to medieval settlement and agriculture. -

North York Moors Local Plan

North York Moors Local Plan Infrastructure Assessment This document includes an assessment of the capacity of existing infrastructure serving the North York Moors National Park and any possible need for new or improved infrastructure to meet the needs of planned new development. It has been prepared as part of the evidence base for the North York Moors Local Plan 2016-35. January 2019 2 North York Moors Local Plan – Infrastructure Assessment, February 2019. Contents Summary ....................................................................................................................................... 5 1. Introduction ................................................................................................................................. 6 2. Spatial Portrait ............................................................................................................................ 8 3. Current Infrastructure .................................................................................................................. 9 Roads and Car Parking ........................................................................................................... 9 Buses .................................................................................................................................... 13 Rail ....................................................................................................................................... 14 Rights of Way.......................................................................................................................