Note to Users

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

(Hg.) Menschliches Handeln Als Improvisation. Sozial- Und Musikwissenschaftliche Perspektiven

Ronald Kurt, Klaus Näumann (Hg.) Menschliches Handeln als Improvisation 2008-02-22 10-12-18 --- Projekt: transcript.titeleien / Dokument: FAX ID 0302171630609556|(S. 1 ) T00_01 schmutztitel - 754.p 171630609564 2008-02-22 10-12-18 --- Projekt: transcript.titeleien / Dokument: FAX ID 0302171630609556|(S. 2 ) T00_02 seite 2 - 754.p 171630609572 Ronald Kurt, Klaus Näumann (Hg.) Menschliches Handeln als Improvisation. Sozial- und musikwissenschaftliche Perspektiven 2008-02-22 10-12-18 --- Projekt: transcript.titeleien / Dokument: FAX ID 0302171630609556|(S. 3 ) T00_03 titel - 754.p 171630609580 Bibliografische Information der Deutschen Bibliothek Die Deutsche Bibliothek verzeichnet diese Publikation in der Deutschen Nationalbibliografie; detaillierte bibliografische Daten sind im Internet über http://dnb.ddb.de abrufbar. © 2008 transcript Verlag, Bielefeld This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 3.0 License. Umschlaggestaltung: Kordula Röckenhaus, Bielefeld Umschlagabbildung: Matthias Kunert: Kindergeburtstag (3/5), © Photocase 2008 Lektorat & Satz: Ronald Kurt, Klaus Näumann Druck: Majuskel Medienproduktion GmbH, Wetzlar ISBN 978-3-89942-754-7 Gedruckt auf alterungsbeständigem Papier mit chlorfrei gebleichtem Zellstoff. Besuchen Sie uns im Internet: http://www.transcript-verlag.de Bitte fordern Sie unser Gesamtverzeichnis und andere Broschüren an unter: [email protected] 2008-02-22 10-12-18 --- Projekt: transcript.titeleien / Dokument: FAX ID 0302171630609556|(S. 4 ) T00_04 impressum -

Music Outside? the Making of the British Jazz Avant-Garde 1968-1973

Banks, M. and Toynbee, J. (2014) Race, consecration and the music outside? The making of the British jazz avant-garde 1968-1973. In: Toynbee, J., Tackley, C. and Doffman, M. (eds.) Black British Jazz. Ashgate: Farnham, pp. 91-110. ISBN 9781472417565 There may be differences between this version and the published version. You are advised to consult the publisher’s version if you wish to cite from it. http://eprints.gla.ac.uk/222646/ Deposited on 28 August 2020 Enlighten – Research publications by members of the University of Glasgow http://eprints.gla.ac.uk Race, Consecration and the ‘Music Outside’? The making of the British Jazz Avant-Garde: 1968-1973 Introduction: Making British Jazz ... and Race In 1968 the Arts Council of Great Britain (ACGB), the quasi-governmental agency responsible for providing public support for the arts, formed its first ‘Jazz Sub-Committee’. Its main business was to allocate bursaries usually consisting of no more than a few hundred pounds to jazz composers and musicians. The principal stipulation was that awards be used to develop creative activity that might not otherwise attract commercial support. Bassist, composer and bandleader Graham Collier was the first recipient – he received £500 to support his work on what became the Workpoints composition. In the early years of the scheme, further beneficiaries included Ian Carr, Mike Gibbs, Tony Oxley, Keith Tippett, Mike Taylor, Evan Parker and Mike Westbrook – all prominent members of what was seen as a new, emergent and distinctively British avant-garde jazz scene. Our point of departure in this chapter is that what might otherwise be regarded as a bureaucratic footnote in the annals of the ACGB was actually a crucial moment in the history of British jazz. -

Download Publication

CONTENTS History The Council is appointed by the Muster for Staff The Arts Council of Great Britain wa s the Arts and its Chairman and 19 othe r Chairman's Introduction formed in August 1946 to continue i n unpaid members serve as individuals, not Secretary-General's Prefac e peacetime the work begun with Government representatives of particular interests o r Highlights of the Year support by the Council for the organisations. The Vice-Chairman is Activity Review s Encouragement of Music and the Arts. The appointed by the Council from among its Arts Council operates under a Royal members and with the Minister's approval . Departmental Report s Charter, granted in 1967 in which its objects The Chairman serves for a period of five Scotland are stated as years and members are appointed initially Wales for four years. South Bank (a) to develop and improve the knowledge , Organisational Review understanding and practice of the arts , Sir William Rees-Mogg Chairman Council (b) to increase the accessibility of the art s Sir Kenneth Cork GBE Vice-Chairma n Advisory Structure to the public throughout Great Britain . Michael Clarke Annual Account s John Cornwell to advise and co-operate wit h Funds, Exhibitions, Schemes and Awards (c) Ronald Grierson departments of Government, local Jeremy Hardie CB E authorities and other bodies . Pamela, Lady Harlec h Gavin Jantje s The Arts Council, as a publicly accountable Philip Jones CB E body, publishes an Annual Report to provide Gavin Laird Parliament and the general public with an James Logan overview of the year's work and to record al l Clare Mullholland grants and guarantees offered in support of Colin Near s the arts. -

Contact: a Journal for Contemporary Music (1971-1988) Citation

Contact: A Journal for Contemporary Music (1971-1988) http://contactjournal.gold.ac.uk Citation Barry. Malcolm. 1977-1978. ‘Review of Company 1 (Maarten van Regteren Altena, Derek Bailey, Tristan Honsinger, Evan Parker) and Company 2 (Derek Bailey, Anthony Braxton, Evan Parker)’. Contact, 18. pp. 36-39. ISSN 0308-5066. ! Director Professor Frederick Rimmer MA B M us FRco Secretary and Librarian James. L McAdam BM us FRco Scottish R Music Archive with the support of the Scottish Arts Council for the documentation and study of Scottish music information on all matters relating to Scottish composers and Scottish music printed and manuscript scores listening facilities: tape and disc recordings Enquiries and visits welcomed: full-time staff- Mr Paul Hindmarsh (Assistant Librarian) and Miss Elizabeth Wilson (Assistant Secretary) Opening Hours: Monday to Friday 9.30 am- 5.30 pm Monday & Wednesday 6.00-9.00 pm Saturday 9.30 am- 12.30 pm .. cl o University of Glasgow 7 Lily bank Gdns. Glasgow G 12 8RZ Telephone 041-334 6393 37 INCUS it RECORDS INCUS RECORDS/ COMPATIBLE RECORDING AND PUBLISHING LTD. is a self-managed company owned and operated by musicians. The company was founded in 1970, motivated partly by the ideology of self-determination and partly by the absence of an acceptable alternative. The spectrum of music issued has been broad, but the musical policy of the company is centred on improvisation. Prior to 1970 the innovative musician had a relationship with the British record industry that could only be improved on. To be offered any chance to make a record at all was already a great favour and somehow to question the economics (fees, royalties, publishing) would certainly have been deemed ungrateful. -

A More Attractive ‘Way of Getting Things Done’ Freedom, Collaboration and Compositional Paradox in British Improvised and Experimental Music 1965-75

A more attractive ‘way of getting things done’ freedom, collaboration and compositional paradox in British improvised and experimental music 1965-75 Simon H. Fell A thesis submitted to the University of Huddersfield in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy The University of Huddersfield September 2017 copyright statement i. The author of this thesis (including any appendices and/or schedules to this thesis) owns any copyright in it (the “Copyright”) and he has given The University of Huddersfield the right to use such Copyright for any administrative, promotional, educational and/or teaching purposes. ii. Copies of this thesis, either in full or in extracts, may be made only in accordance with the regulations of the University Library. Details of these regulations may be obtained from the Librarian. This page must form part of any such copies made. iii. The ownership of any patents, designs, trade marks and any and all other intellectual property rights except for the Copyright (the “Intellectual Property Rights”) and any reproductions of copyright works, for example graphs and tables (“Reproductions”), which may be described in this thesis, may not be owned by the author and may be owned by third parties. Such Intellectual Property Rights and Reproductions cannot and must not be made available for use without the prior written permission of the owner(s) of the relevant Intellectual Property Rights and/or Reproductions. 2 abstract This thesis examines the activity of the British musicians developing a practice of freely improvised music in the mid- to late-1960s, in conjunction with that of a group of British composers and performers contemporaneously exploring experimental possibilities within composed music; it investigates how these practices overlapped and interpenetrated for a period. -

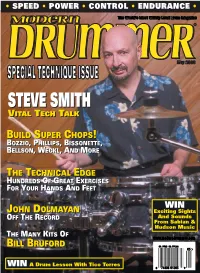

Steve Smith Steve Smith

• SPEED • POWER • CONTROL • ENDURANCE • SPECIAL TECHNIQUE ISSUE STEVESTEVE SMITHSMITH VVITALITAL TTECHECH TTALKALK BBUILDUILD SSUPERUPER CCHOPSHOPS!! BBOZZIOOZZIO,, PPHILLIPSHILLIPS,, BBISSONETTEISSONETTE,, BBELLSONELLSON,, WWECKLECKL,, AANDND MMOREORE TTHEHE TTECHNICALECHNICAL EEDGEDGE HHUNDREDSUNDREDS OOFF GGREATREAT EEXERCISESXERCISES FFOROR YYOUROUR HHANDSANDS AANDND FFEETEET WIN JJOHNOHN DDOLMAYANOLMAYAN Exciting Sights OOFFFF TTHEHE RRECORDECORD And Sounds From Sabian & Hudson Music TTHEHE MMANYANY KKITSITS OOFF BBILLILL BBRUFORDRUFORD $4.99US $6.99CAN 05 WIN A Drum Lesson With Tico Torres 0 74808 01203 9 Contents ContentsVolume 27, Number 5 Cover photo by Alex Solca STEVE SMITH You can’t expect to be a future drum star if you haven’t studied the past. As a self-proclaimed “US ethnic drummer,” Steve Smith has made it his life’s work to explore the uniquely American drumset— and the way it has shaped our music. by Bill Milkowski 38 Alex Solca BUILDING SUPER CHOPS 54 UPDATE 24 There’s more than one way to look at technique. Just ask Terry Bozzio, Thomas Lang, Kenny Aronoff, Bill Bruford, Dave Weckl, Paul Doucette Gregg Bissonette, Tommy Aldridge, Mike Mangini, Louie Bellson, of Matchbox Twenty Horacio Hernandez, Simon Phillips, David Garibaldi, Virgil Donati, and Carl Palmer. Gavin Harrison by Mike Haid of Porcupine Tree George Rebelo of Hot Water Music THE TECHNICAL EDGE 73 Duduka Da Fonseca An unprecedented gathering of serious chops-increasing exercises, samba sensation MD’s exclusive Technical Edge feature aims to do no less than make you a significantly better drummer. Work out your hands, feet, and around-the-drums chops like you’ve never worked ’em before. A DIFFERENT VIEW 126 TOM SCOTT You’d need a strongman just to lift his com- plete résumé—that’s how invaluable top musicians have found saxophonist Tom Scott’s playing over the past three decades. -

Recorded Jazz in the 20Th Century

Recorded Jazz in the 20th Century: A (Haphazard and Woefully Incomplete) Consumer Guide by Tom Hull Copyright © 2016 Tom Hull - 2 Table of Contents Introduction................................................................................................................................................1 Individuals..................................................................................................................................................2 Groups....................................................................................................................................................121 Introduction - 1 Introduction write something here Work and Release Notes write some more here Acknowledgments Some of this is already written above: Robert Christgau, Chuck Eddy, Rob Harvilla, Michael Tatum. Add a blanket thanks to all of the many publicists and musicians who sent me CDs. End with Laura Tillem, of course. Individuals - 2 Individuals Ahmed Abdul-Malik Ahmed Abdul-Malik: Jazz Sahara (1958, OJC) Originally Sam Gill, an American but with roots in Sudan, he played bass with Monk but mostly plays oud on this date. Middle-eastern rhythm and tone, topped with the irrepressible Johnny Griffin on tenor sax. An interesting piece of hybrid music. [+] John Abercrombie John Abercrombie: Animato (1989, ECM -90) Mild mannered guitar record, with Vince Mendoza writing most of the pieces and playing synthesizer, while Jon Christensen adds some percussion. [+] John Abercrombie/Jarek Smietana: Speak Easy (1999, PAO) Smietana -

Jazzletter 93024--024-0 April 1993 V01

» » G606 L665 P.O. Box 240 Ojai, Calif. Jazzletter 93024--024-0 April 1993 V01. 12 Na 4 Carl Barriteau, born in Trinidad February 7, 1914, grew up Come Back Last Summer in Maracaibo, Venezuela. He moved to London in the late Part Two 1930s and played with Ken (Snake Hips) Johnson’s West Indian Swing Band. He formed his own recording group in the middle ‘By this time it was Christmas, the end of ’52,‘ Kermy said. ‘I of World War II and entertained British and American troops left Canada atthe end of September or early October. after the war, in Europe, North Africa, and Southeast Asia. ‘I read that they needed helpers in the post office for the ‘I’m not sure when I went with that band,‘ Kenny said. Christmas mail. So I got a job doing that. But meanwhile I’d ‘Wait a minute, I can pin it, because it was the year I came met Doreen on the telephone. The young Scotsman used to go over to visit,‘ I said. ‘You were with that band in 1954.‘ with Doreen’s girlfriend, tmbeknown to the guy he was living ‘Carl was great,‘ Kenny said. ‘I loved working for him. I 'rith. Doreen rang up one day to say that her girlfriend couldn’t really shouldn’t have taken the job, because I didn’t have the make this date with the Scotsman. So being young and stupid, chops for it. It was a really hard book. There was a front line I suppose, I started to kid around with her on the phone, and of about five people. -

Extreme Matt-Itude Holidaygift Guide Ikue • Ivo • Joel • Rarenoise • Event Mori Perelman Press Records Calendar December 2013

DECEMBER 2013 - ISSUE 140 YOUR FREE GUIDE TO THE NYC JAZZ SCENE NYCJAZZRECORD.COM MATT WILSON EXTREME MATT-ITUDE HOLIDAYGIFT GUIDE IKUE • IVO • JOEL • RARENOISE • EVENT MORI PERELMAN PRESS RECORDS CALENDAR DECEMBER 2013 DAVID SANBORN FOURPLAY CLAUDIO RODITI QUARTET SUNDAY BRUNCH RESIDENCY DEC 3 - 8 DEC 10 - 15 TRIBUTE TO DIZZY GILLESPIE DEC 1, 8, 15, 22, & 29 CHRIS BOTTI ANNUAL HOLIDAY RESIDENCY INCLUDING NEW YEAR’S EVE! DEC 16 - JAN 5 JERMAINE PAUL KENDRA ROSS WINNER OF “THE VOICE” CD RELEASE DEC 2 DEC 9 LATE NIGHT GROOVE SERIES RITMOSIS DEC 6 • CAMILLE GANIER JONES DEC 7 • SIMONA MOLINARI DEC 13 • GIULIA VALLE DEC 14 VICKIE NATALE DEC 20 • RACHEL BROTMAN DEC 21 • BABA ISRAEL & DUV DEC 28 TELECHARGE.COM TERMS, CONDITIONS AND RESTRICTIONS APPLY “BEST JAZZ CLUBS OF THE YEAR 2012” SMOKE JAZZ & SUPPER CLUB • HARLEM, NEW YORK CITY FEATURED ARTISTS / 7:00, 9:00 & 10:30pm HOLIDAY EVENTS / 7:00, 9:00 & 10:30pm Fri & Sat, Dec 6 & 7 Sun, Dec 15 SMOKE JAVON JACKSON BAND GEORGE BURTON’S CHRISTMAS YULELOG Winter / Spring 2014 Javon Jackson (tenor saxophone) • Orrin Evans (piano) Thu, Dec 19 Santi DeBriano (bass) • Jason Tiemann (drums) “A NAT ‘KING’ COLE CHRISTMAS” SESSIONS Fri & Sat, Dec 13 & 14 ALAN HARRIS QUARTET BILL CHARLAP TRIO COMPACT DISC AND DOWNLOAD TITLES Bill Charlap (piano) • Peter Washington (bass) COLTRANE FESTIVAL / 7:00, 9:00 & 10:30pm Kenny Washington (drums) Mon, Dec 23 - Wed, Dec 25 Fri, Sat & Sun, Dec 20, 21 & 22 ERIC ALEXANDER QUARTET RENEE ROSNES QUARTET FEATURING LOUIS HAYES Steve Nelson (vibraphone) • Renee Rosnes (piano) Eric Alexander (tenor saxophone) • Harold Mabern (piano) Peter Washington (bass) • Lewis Nash (drums) John Webber (bass) • Louis Hayes (drums) Thu, Dec 26 - Wed, Jan 1 ERIC ALEXANDER SEXTET ONE NIGHT ONLY / 7:00, 9:00 & 10:30pm FEAT. -

Dean Free Improv

"phenomenal musicianship" (Sydney Morning Herald, 1995) "incredible interaction" (The Wire, UK, 1996) "cutting edge ... eclectic ... consummate" (BBC Radio 3, UK, 1997) "intelligent musical innovation .... the sound world took the ear into alluring and unexplored domains" (Sydney Morning Herald, 2005) "those doyens of computerised music" (Sydney Morning Herald, 2008) "creates amazing soundscapes" (Sydney Morning Herald, December 2009) On Roger Dean: ‘trail-blazing’, 'earthy approach', ‘surprising and disquieting’, ‘exquisite’, ‘crystalline or tumultuous’, ‘brilliant musicianship’, ‘exploding with vivacity'. (John Shand of the Sydney Morning Herald, 2013) An activity of austraLYSIS, an international ensemble creating and performing new sound and intermedia arts, based in Sydney, Australia. www.australysis.com Roger Dean: Free Improviser/piano and/or laptop A major strand in the work of Roger Dean (composer/improviser) is Free Improvisation, solo and group, with Dean performing on piano and/or laptop. He has performed free improv at iconic venues such as the Little Theatre Club (1970’s-80s) and Café Oto (2011,2013--), and on the South Bank (London), at Bracknell Jazz Festival, at the ISCM World Music Days (Denmark), and around Asia and Australasia. He has worked in solo, duo and ensemble contexts, with people such as Derek Bailey, Connie Bauer, Jim Fulkerson, Barry Guy, The London Jazz Composers’ Orchestra, Oren Marshall, Maggie Nichols, Tony Oxley, Evan Parker, Eddie Prevost, Paul Rutherford, Veleroy Spall and Ken Wheeler. He made some innovative free improvisation recordings such as the 1970-1987 LPs Dualyses, and Superimpositions (reissued on CD in 2013), and included solo free improvisation on many other albums (such as his very first, LYSIS Live, 1975; reissued on CD by Future Music Records). -

Free Improvisation Information Service Over the Internet

Purdue University Purdue e-Pubs Proceedings of the IATUL Conferences 1996 IATUL Proceedings Free Improvisation Information Service over the Internet Peter Stubley University of Sheffield Peter Stubley, "Free Improvisation Information Service over the Internet." Proceedings of the IATUL Conferences. Paper 46. https://docs.lib.purdue.edu/iatul/1996/papers/46 This document has been made available through Purdue e-Pubs, a service of the Purdue University Libraries. Please contact [email protected] for additional information. New sites, new sounds: a functioning electronic information service on free improvisation over the Internet Peter Stubley , Sub-Librarian, St. George’s Library, University of Sheffield, United Kingdom Introduction This paper describes a wholly electronic service with real information content that has been running over the Internet since January 1995. The particular aspects that mark this out as different from many Web sites are considered in the paper, as well as a comparison with print-based equivalents, but I will begin with a consideration of the subject focus of the service. Free improvisation The origins of free improvisation date back to the mid 1960s and lie in a mixture of the avant garde end of jazz – Ornette Coleman, John Coltrane, Cecil Taylor – and contemporary classical music – Schoenberg, Webern. In fact, at this time, established methods of improvising, using particular forms of approach, were being challenged in rather different ways in the US and in Europe. But even within Europe there were no (fortunately) co-ordinated stirrings, and musicians in three countries in particular – England, Holland and Germany – are acknowledged as developing new methods of playing improvised music, working broadly independently of each other (which is not to say there weren’t others). -

Johannes Bauer

Johannes Bauer Discography | Diskographie 15.03.2019 2019 – 03 Zlatko Kaucic – Diversity Not Two Records, MW 969-2 Not Two Records, MW 969-2 Zlatko Kaučič – Ground Drums, Percussion Johannes Bauer – Trombone CD#5 »MED-ANA« 1. Med-Ana – 11:34 / 2. Med-Ana – 3:34 / 3. Med-Ana – 8:21 / 4. Med-Ana – 8:52 / 5. Med-Ana – 2:53 / 6. Šmartno Suita – 23:55 Tracks 1 to 5 – Recorded at Medana “Old Movie Theatre” on September 15, 2012. Track 6 – Recorded at Brda Contemporary Music Festival, Italy on September 13, 2014. 5 CDs in single printed paper-sleeves housed in a sturdy cardboard box-set with a magnetic locking. Contains a 12-page booklet with an interview, line-ups, liner notes and photographs. Only CD #5 with Johannes. 2018 – 01 Jeb Bishop, Matthias Müller, Matthias Muche – Konzert für Hannes Not Two Records, MW 961-2 Jeb Bishop – trombone Matthias Müller – trombone Matthias Muche – trombone 1. 07:39 / 2. 06:07 / 3. 09:03 / 4. 07.59 / 5. 07:40 / 6. 07:09 Recorded live at Stadtgarten Köln on May 5th 2016 Tribut Recording Johannes Bauer Discography 2 | 44 2017 – 01 Johannes Bauer / Peter Broetzmann – Blue City Trost Records, TR155 Peter Brötzmann: tenor & alt sax, tarogato, b-flat clarinet Johannes Bauer: trombone 1 Name That Thing 28:42 2 Blue City 5:11 3 Poppy Cock 15:25 4 Heard And Seen 14:05 5 Hot Mess 6:10 Mastered By – Martin Siewer, Photography – Philippe Renaud Live at Blue City Osaka / Japan 16. October 1997 2014 – 02 Barry Guy New Orchestra Small Formations – Mad Dogs On The Loose Not Two Records , MW925-2, 4 × CD, Album Barry Guy bass