IFRC Guidance on the Generalised Use of Cloth Face Masks During the COVID-19 Pandemic

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

COVID-19 Guidance on Cloth Face Masks This Document Provides Guidance on Best Practices for the Use of Nonmedical Face Masks, Considering COVID-19

COVID-19 Guidance on Cloth Face Masks This document provides guidance on best practices for the use of nonmedical face masks, considering COVID-19. Currently, institutions have varying guidelines and Water Mission has taken these under advisement to produce recommendations for the ministry. Each country program should make sure to comply with national and local guidance, if stricter guidelines are in enforced. Water Mission Recommendations Taking into consideration current guidelines provided by the World Health Organization (WHO), the Center for Disease Control (CDC) (see Appendix 1) and other research, Water Mission makes the following recommendations for the use of cloth face masks in relation to COVID-19. Category Minimum Requirements When to use a face • Water Mission recommends the use of cloth face masks according to the mask risk level in each country program (see table below). o As of 4/27/20, ALL STAFF ARE REQUIRED TO WEAR APPROVED FACE MASKS AT ALL TIMES Approved face • Two-layer cloth face masks (see specifications below) masks • Single-use nonmedical face masks Provision of face • All Water Mission staff should be provided with five (5) cloth face masks masks per person (plus laundry soap for washing) • If using single-use face masks, Water Mission staff should be provided with two (2) face masks per person, per day Face mask training • All staff members must be trained on proper face mask use and management (click link for training presentation) Proper face mask • Wash hands with water and soap, or use alcohol-based hand -

Universal PPE Guidelines and Faqs (As of August 2, 2021)

Universal PPE Guidelines and FAQs (as of August 2, 2021) Guidance was issued on July 27, 2021, by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) that raises concerns of increased COVID-19 transmission due to the Delta variant. As a result, in alignment with the CDC, Nebraska Medicine is making modifications to the Universal PPE Guidelines to support the increasing numbers of COVID-19 cases in the community. Vaccination remains the most effective way to prevent transmission of disease and is the only way to prevent severe illness with risk of hospitalization and death. Guidance will be updated and/or expanded based on the level of community spread of COVID- 19, the proportion of the population that is fully vaccinated, the rapidly evolving science on COVID-19 vaccines, the understanding of COVID-19 variants and employee health data related to COVID-19 exposure. For the purposes of this document, people are considered fully vaccinated after receiving the full series of the following COVID-19 vaccines: Pfizer/BioNTech, Astrazeneca-SK Bio, Serum Institute of India, Johnson and Johnson (J&J/Janseen), Moderna, Novavax, Sinovac, and Sinopharm Key Points Applicable for ALL Nebraska Medicine Sites: Regardless of vaccination status: o Masks will be required in all clinical settings. o Masks will be required whenever a colleague is indoors in the presence of a patient and/or visitor. o Masks must be doffed and discarded when leaving a droplet/contact precautions isolation room. A new mask must be donned by the colleague immediately after leaving this type of isolation. When masks are used for droplet precautions, the mask becomes contaminated during patient encounters via large droplet particle transmission. -

Control Practices for Delivering Direct Student Support Services

MINNESOTA DEPARTMENT OF HEALTH Recommendations for Infection Prevention and Control Practices for Delivering Direct Student Support Services 5 / 2 7 /2021 This guidance provides strongly recommended practices to school staff on the use of protective equipment to reduce the risk of COVID-19 and other communicable disease transmission when delivering direct student support services that require close, prolonged contact. This guidance applies to services delivered in kindergarten through grade 12 special and general education, pre-kindergarten programs, birth to three-part C under IDEA, and school-based child care programs. References: . CDC: Information for School Nurses and Other Healthcare Personnel (HCP) Working in Schools and Child Care Settings (www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/community/schools-childcare/school- nurses-hcp.html) . CDC: Interim Infection Prevention and Control Recommendations for Healthcare Personnel During the Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19) Pandemic (www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019- ncov/hcp/infection-control-recommendations.html) . CDC: Updated Healthcare Infection Prevention and Control Recommendations in Response to COVID-19 Vaccination (www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/hcp/infection-control-after- vaccination.html) . CDC: Guidance for Direct Service Providers (www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/need-extra- precautions/direct-service-providers.html) . AAP: COVID-19 Guidance for Safe Schools (services.aap.org/en/pages/2019-novel-coronavirus- covid-19-infections/clinical-guidance/covid-19-planning-considerations-return-to-in-person- education-in-schools/) 1 of 13 RECOMMENDATIONS FOR INFECTION PREVENTION AND CONTROL PRACTICES FOR DELIVERING DIRECT STUDENT SUPPORT SERVICES Basic principles of infection control Face mask recommendations The following measures are strongly recommended when direct student support services are being provided to a student: . -

LEO Facemasks-050820.Pdf

1-877-897-6646 Lands’ End Business helps your brand succeed with quality business and uniform apparel, legendary service and real value. Cotton Cloth Face Mask Style 521006 Color White Price $14.85/3pack These are designed to be used when FDA masks (e.g., N95 surgical masks) are not available. Not intended as Personal Protective Equipment (PPE)* - 3-ply 100% cotton, 4 oz Jersey knit - Anti-microbial fabric finish - Machine wash separately in cold water. Use only non-chlorine bleach if needed. Tumble dry low. Do not use fabric softener. Do not iron. Wash dark colors separately. May be washed up to 20 times. - Imported This fabric is OEKO-TEX® certified. 7” Relaxed Approx 3.5” Extended Approx 4.5” .375” 3.5” 7” .375” Poly/Cotton Cloth Face Mask Style 521005 Colors White, Light Blue, Royal Blue, Navy Blue, Gray Price $7.50/3pack These are designed to be used when FDA masks (e.g., N95 surgical masks) are not available. Not intended as Personal Protective Equipment (PPE)* - Fabric: 2-ply 65% polyester/35% cotton, 4.3 oz poplin - Machine wash separately in warm water. Tumble dry low. Do not use fabric softener. Do not iron. Wash dark colors separately. May be washed up to 75 times. - Imported This mask is OEKO-TEX® Standard 100 certified. 4” Pleats .5” Open upwards 6.5” Relaxed Approx 3” 8” Extended Approx 4” .25” BioSmart® is a patented Milliken® technology that binds chlorine in the wash cycle. BioSmart® garments must be washed in a bleach cycle to charge the fabric with chlorine initially, and to recharge during each wash. -

Facemasks in the Protection of Hospitals

FACEMASKS IN THE PROTECTION OF HOSPITALS HEALTHCARE WORKERS (HCW) IN RESOURCE POOR SETTINGS Dr. Abrar Ahmad Chughtai This thesis is in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy School of Public Health and Community Medicine UNSW Medicine May 2015 1 THE UNIVERSITY OF NEW SOUTH WALES Thesis/Dissertation Sheet Surname or Fam1ly name Chughta1 F1rst name Abrar Other name/s Ahmad Abbreviation for degree as g1ven m the Umvers1ty calendar PhD School Public Health and Commun1ty Medicine Faculty Medicine T1tle Facemasks m the protection of hosp1tals healthcare workers (HCWs) in resource poor settings Abstract 350 words maximum: (PLEASE TYPE) Currently there is an ongoing debate and a dearth of evidence around the efficacy of facemasks and respirators. Most studies have been observational and there is a lack of trial data around use and re-use of facemasks in the healthcare setting. Due to the lack of high quality studies, I hypothesised that there would be huge variations in the policies and practices around the use of facemasks and respirators in the healthcare setting. This thesis therefore aims to examine the policies and practices around the use of these products in low resource countries. Five studies were conducted at varying administrative levels. In the first study, publicly available policies and guidelines around the use of facemasks/respirators were examined to describe areas of consistency, as well as gaps in the recommendations. In the second study, infection control stakeholders were interviewed from China, Pakistan and Vietnam to further explore the issues, which arose during the guideline review. Next, hospitals from the three countries were surveyed to examine practices around the use of facemasks/ respirators and to examine the translation of policies into practice. -

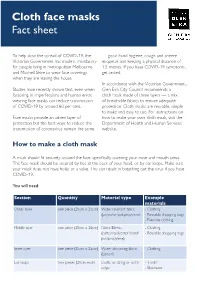

Cloth Face Masks Fact Sheet

Cloth face masks Fact sheet To help slow the spread of COVID-19, the — good hand hygiene, cough and sneeze Victorian Government has made it mandatory etiquette and keeping a physical distance of for people living in metropolitan Melbourne 1.5 metres. If you have COVID-19 symptoms, and Mitchell Shire to wear face coverings get tested. when they are leaving the house. In accordance with the Victorian Government, Studies have recently shown that, even when Glen Eira City Council recommends a factoring in imperfections and human error, cloth mask made of three layers — a mix wearing face masks can reduce transmission of breathable fabrics to ensure adequate of COVID-19 by around 60 per cent. protection. Cloth masks are reusable, simple to make and easy to use. For instructions on Face masks provide an added layer of how to make your own cloth mask, visit the protection but the best ways to reduce the Department of Health and Human Services’ transmission of coronavirus remain the same website. How to make a cloth mask A mask should fit securely around the face, specifically covering your nose and mouth areas. The face mask should be secured by ties at the back of your head, or by ear loops. Make sure your mask does not have holes or a valve. This can result in breathing out the virus if you have COVID-19. You will need: Section Quantity Material type Example materials Outer layer one piece (25cm x 25cm) Water resistant fabric - Clothing (polyester/pokpropylene) - Reusable shopping bags - Exercise clothing Middle layer one piece (25cm x 25cm) Fabric Blends - Clothing (cotton/polyester blend/ - Reusable shopping bags polypropylene) Inner layer one piece (25cm x 25cm) Water-absorbing fabric - Clothing (cotton) Ear loops two pieces (20cm each) Elastic or string or cloth - T-shirt strips - Shoelaces Cloth face masks Fact sheet Instructions 1. -

05/14/20 City Council Special Meeting

CITY OF MORRO BAY CITY COUNCIL AGENDA The City of Morro Bay provides essential public services and infrastructure to maintain a safe, clean and healthy place for residents and visitors to live, work and play. NOTICE OF SPECIAL MEETING Thursday, May 14, 2020 – 2:00 P.M. Held Via Teleconference ESTABLISH QUORUM AND CALL TO ORDER PUBLIC COMMENT FOR ITEMS ON THE AGENDA Pursuant to Section 3 of Executive Order N-29-20, issued by Governor Newsom on March 17, 2020, this Meeting will be conducted telephonically through Zoom and broadcast live on Cable Channel 20 and streamed on the City website (click here to view). Please be advised that pursuant to the Executive Order, and to ensure the health and safety of the public by limiting human contact that could spread the COVID-19 virus, the Veterans’ Hall will not be open for the meeting. Public Participation: In order to prevent and mitigate the effects of the COVID-19 pandemic, and limit potential spread within the City of Morro Bay, in accordance with Executive Order N-29-20, the City will not make available a physical location from which members of the public may observe the meeting and offer public comment. Remote public participation is allowed in the following ways: • Community members are encouraged to submit agenda correspondence in advance of the meeting via email to the City Clerk’s office at [email protected] prior to the meeting and will be published on the City website with a final update one hour prior to the meeting start time. -

Advanced Research and Development of Face Masks and Respirators Pre and Post the Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19) Pandemic: a Critical Review

polymers Review Advanced Research and Development of Face Masks and Respirators Pre and Post the Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19) Pandemic: A Critical Review Ebuka A. Ogbuoji 1,†, Amr M. Zaky 2,† and Isabel C. Escobar 1,* 1 Department of Chemical and Materials Engineering, University of Kentucky, Lexington, KY 40506, USA; [email protected] 2 BioMicrobics Inc., 16002 West 110th Street, Lenexa, KS 66219, USA; [email protected] * Correspondence: [email protected]; Tel.: +1-859-257-7990 † Equal first authorship. Abstract: The outbreak of the COVID-19 pandemic, in 2020, has accelerated the need for personal protective equipment (PPE) masks as one of the methods to reduce and/or eliminate transmission of the coronavirus across communities. Despite the availability of different coronavirus vaccines, it is still recommended by the Center of Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), World Health Or- ganization (WHO), and local authorities to apply public safety measures including maintaining social distancing and wearing face masks. This includes individuals who have been fully vacci- nated. Remarkable increase in scientific studies, along with manufacturing-related research and development investigations, have been performed in an attempt to provide better PPE solutions during the pandemic. Recent literature has estimated the filtration efficiency (FE) of face masks and Citation: Ogbuoji, E.A.; Zaky, A.M.; respirators shedding the light on specific targeted parameters that investigators can measure, detect, Escobar, I.C. Advanced Research and evaluate, and provide reliable data with consistent results. This review showed the variability in test- Development of Face Masks and ing protocols and FE evaluation methods of different face mask materials and/or brands. -

Viral Filtration Efficiency of Fabric Masks Compared with Surgical And

pathogens Communication Viral Filtration Efficiency of Fabric Masks Compared with Surgical and N95 Masks Harriet Whiley * , Thilini Piushani Keerthirathne, Muhammad Atif Nisar, Mae A. F. White and Kirstin E. Ross Environmental Health, College of Science and Engineering, Flinders University, GPO Box 2100, Adelaide 5001, Australia; Thilini.Ke@flinders.edu.au (T.P.K.); Muhammadatif.Nisar@flinders.edu.au (M.A.N.); Mae.White@flinders.edu.au (M.A.F.W.); Kirstin.Ross@flinders.edu.au (K.E.R.) * Correspondence: Harriet.Whiley@flinders.edu.au; Tel.: +61-(08)-7221-8580 Received: 15 August 2020; Accepted: 16 September 2020; Published: 17 September 2020 Abstract: In response to the Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic, current modeling supports the use of masks in community settings to reduce the transmission of SARS-CoV-2. However, concerns have been raised regarding the global shortage of medical grade masks and the limited evidence on the efficacy of fabric masks. This study used a standard mask testing method (ASTM F2101-14) and a model virus (bacteriophage MS2) to test the viral filtration efficiency (VFE) of fabric masks compared with commercially available disposable, surgical, and N95 masks. Five different types of fabric masks were purchased from the ecommerce website Etsy to represent a range of different fabric mask designs and materials currently available. One mask included a pocket for a filter; which was tested without a filter, with a dried baby wipe, and a section of a vacuum cleaner bag. A sixth fabric mask was also made according to the Victorian Department of Health and Human Services (DHHS) guidelines (Australia). -

How to Make a Homemade Cloth Face Mask Work Better Based on Science

How to Make A Homemade Cloth Face Mask Work Better Based On Science Remember: The COMBINATION of fit and filtration is the most important when wearing a mask1! Wearing a homemade cloth mask does not provide complete protection. (Stay home!) Wash your hands!2 When you put on or take off a mask, your Wear it right! hands touch your face. Any time you place 3 your hands on your face, you can spread ϐ Remove when wet because moisture affects filtration the virus from your hands to your face. ϐ Distance yourself from people3 (stand back when someone coughs; side-step the direct spray) ϐ Consider using a pantyhose tube (open on both ends) to hold the face mask in place to prevent air leakage10 Design (which also adds another layer of fabric) ϐ Create a snug mask that fits around the nose and mouth for either kids or adults3,4 Most Fabric particles enter from a loose seal on the face, not the filter5 ϐ Researchers have different opinions ϐ Do NOT use a rectangular shaped design with about which type of fabric to use. loops that connect behind the ears because Consider using: they do NOT filter air pollution particles well6 ϐ Hanes sweatshirt material9 1 ϐ Know that any mask is better when the seal on ϐ Tea towel 7 4 the face is good ϐ 100% cotton t-shirt (remove when ϐ Use a cone or tetrahedral shaped pattern moist) 3 because it filters the most air pollution ϐ Use multiple layers of fabric 6 particles ϐ Use a soft fabric because stiff materials may leak more organisms around the If you have to create a rectangular design: edges of the mask8 ϐ Select a fine fabric with a tight weave3 ϐ Use pleats to improve filtration efficiency8 ϐ Create a mask that extends far back over the cheeks and under the chin to prevent leakage8 1. -

Personal Protective Equipment) by All NYP Employees May 27, 2021 (Replaces May 1, 2021 Faqs)

FAQs for Universal Mask Use and Universal PPE (Personal Protective Equipment) by All NYP Employees May 27, 2021 (Replaces May 1, 2021 FAQs) UNIVERSAL MASKING REQUIREMENTS IN THE WORKPLACE at NYP, COLUMBIA, AND WEILL CORNELL REMAIN UNCHANGED, REGARDLESS OF COVID-19 VACCINATION STATUS. CDC public health recommendations for fully vaccinated people ONLY apply outside of the workplace and do NOT apply to healthcare settings or to offsite work-related events. Healthcare personnel (HCP) are in close, frequent contact with immunocompromised and other vulnerable patients (or in contact with other HCP who are patient-facing) and therefore should be especially cautious in avoiding scenarios where transmission could occur. These frequently asked questions and answers describe the rationale for universal use of well-fitting masks by ALL NYP employees, not just those providing patient care or working in clinical settings, as well as Columbia and Cornell employees in clinical areas. Additionally, this document explains the rationale for universal PPE (surgical mask, eye protection, N95 respirators for AGPs) for HCP. See Table 1 near the end of this document summarizing mask and other PPE requirements for various clinical and non-clinical scenarios. GENERAL FAQs for FULLY VACCINATED People 1. I am fully vaccinated1. Why do I need to continue to mask and distance in the healthcare setting? While the FDA-authorized COVID-19 vaccines appear to be very effective in preventing COVID-19 infection, no vaccine (including these COVID-19 vaccines) is 100% effective. While the risk is greatly reduced, fully vaccinated people could still get infected if they are exposed to COVID-19, although they are much less likely to develop severe symptoms and require hospitalization. -

N95 Respirator Or Triple Layer Surgical Mask: Radiologist Perspective

Published online: 2021-07-13 COMMENTARY N95 respirator or triple layer surgical mask: Radiologist perspective N95 respirators and surgical masks (face masks) are clearly labelled. The “N95” designation means that when examples of personal protective equipment (PPE) subjected to careful testing, the respirator blocks at least that are used to protect the wearer from airborne 95% of very small (0.3 µm) test particles. The key features particles and from liquid contaminating the face. The of N95 masks are adjustable nose clip (for leak‑proof fit and respirators are designed to reduce inhalation exposure disallows fogging of eyewear), nose foam (for absorption to particulate contaminants (dust, mist, and fume). of perspiration), and headbands. The nose clip is made of The authorities which regulate the quality control for aluminum, nose foam made of polyurethane, filter made of the respirators are Centers for Disease Control and polypropylene, and the cover made of polyester.[3] Prevention (CDC), National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health (NIOSH), and Occupational Safety Respirators in this family are rated as N, R, or P and Health Administration (OSHA). for protection against oils. N (not resistant to oil) means that the respirators cannot be used in an oil Surgical Mask droplet environment; R (somewhat resistant to oil) and P (strongly resistant to oil) mean that these respirators A surgical mask is a loose‑fitting, disposable device that can be used for protection against nonoily and oily creates a physical barrier between the mouth and nose of aerosols. The US National Institute for Occupational the wearer and potential contaminants in the immediate Safety and Health (NIOSH) classifies filtering facepiece environment.