MONTHLY OBSERVER's CHALLENGE Las Vegas

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

August 10Th 2019 August 2019 7:00Pm at the Herrett Center for Arts & Science College of Southern Idaho

Snake River Skies The Newsletter of the Magic Valley Astronomical Society www.mvastro.org Membership Meeting MVAS President’s Message August 2019 Saturday, August 10th 2019 7:00pm at the Herrett Center for Arts & Science College of Southern Idaho. Colleagues, Public Star Party follows at the I hope you found the third week of July exhilarating. The 50th Anniversary of the first Centennial Observatory moon landing was the common theme. I capped my observance by watching the C- SPAN replay of the CBS broadcast. It was not only exciting to watch the landing, but Club Officers to listen to Walter Cronkite and Wally Schirra discuss what Neil Armstrong and Buzz Robert Mayer, President Aldrin was relaying back to us. It was fascinating to hear what we have either accepted or rejected for years come across as something brand new. Hearing [email protected] Michael Collins break in from his orbit above in the command module also reminded me of the major role he played and yet others in the past have often overlooked – Gary Leavitt, Vice President fortunately, he is now receiving the respect he deserves. If you didn’t catch that, [email protected] then hopefully you caught some other commemoration, such as Turner Classic Movies showing For All Mankind, a spellbinding documentary of what it was like for Dr. Jay Hartwell, Secretary all of the Apollo astronauts who made it to the moon. Jim Tubbs, Treasurer / ALCOR For me, these moments of commemoration made reading the moon landing’s [email protected] anniversary issue from the Association of Lunar and Planetary Observers (ALPO) 208-404-2999 come to life as they wrote about the features these astronauts were examining – including the little craters named after the three astronauts. -

Messier Plus Marathon Text

Messier Plus Marathon Object List by Wally Brown & Bob Buckner with additional objects by Mike Roos Object Data - Saguaro Astronomy Club Score is most numbered objects in a single night. Tiebreaker is count of un-numbered objects Observer Name Date Address Marathon Obects __________ Tiebreaker Objects ________ SEQ OBJECT TYPE CON R.A. DEC. RISE TRANSIT SET MAG SIZE NOTES TIME M 53 GLOCL COM 1312.9 +1810 7:21 14:17 21:12 7.7 13.0' NGC 5024, !B,vC,iR,vvmbM,st 12.. NGC 5272, !!,eB,vL,vsmbM,st 11.., Lord Rosse-sev dark 1 M 3 GLOCL CVN 1342.2 +2822 7:11 14:46 22:20 6.3 18.0' marks within 5' of center 2 M 5 GLOCL SER 1518.5 +0205 10:17 16:22 22:27 5.7 23.0' NGC 5904, !!,vB,L,eCM,eRi, st mags 11...;superb cluster M 94 GALXY CVN 1250.9 +4107 5:12 13:55 22:37 8.1 14.4'x12.1' NGC 4736, vB,L,iR,vsvmbM,BN,r NGC 6121, Cl,8 or 10 B* in line,rrr, Look for central bar M 4 GLOCL SCO 1623.6 -2631 12:56 17:27 21:58 5.4 36.0' structure M 80 GLOCL SCO 1617.0 -2258 12:36 17:21 22:06 7.3 10.0' NGC 6093, st 14..., Extremely rich and compressed M 62 GLOCL OPH 1701.2 -3006 13:49 18:05 22:21 6.4 15.0' NGC 6266, vB,L,gmbM,rrr, Asymmetrical M 19 GLOCL OPH 1702.6 -2615 13:34 18:06 22:38 6.8 17.0' NGC 6273, vB,L,R,vCM,rrr, One of the most oblate GC 3 M 107 GLOCL OPH 1632.5 -1303 12:17 17:36 22:55 7.8 13.0' NGC 6171, L,vRi,vmC,R,rrr, H VI 40 M 106 GALXY CVN 1218.9 +4718 3:46 13:23 22:59 8.3 18.6'x7.2' NGC 4258, !,vB,vL,vmE0,sbMBN, H V 43 M 63 GALXY CVN 1315.8 +4201 5:31 14:19 23:08 8.5 12.6'x7.2' NGC 5055, BN, vsvB stell. -

Ghost Hunt Challenge 2020

Virtual Ghost Hunt Challenge 10/21 /2020 (Sorry we can meet in person this year or give out awards but try doing this challenge on your own.) Participant’s Name _________________________ Categories for the competition: Manual Telescope Electronically Aided Telescope Binocular Astrophotography (best photo) (if you expect to compete in more than one category please fill-out a sheet for each) ** There are four objects on this list that may be beyond the reach of beginning astronomers or basic telescopes. Therefore, we have marked these objects with an * and provided alternate replacements for you just below the designated entry. We will use the primary objects to break a tie if that’s needed. Page 1 TAS Ghost Hunt Challenge - Page 2 Time # Designation Type Con. RA Dec. Mag. Size Common Name Observed Facing West – 7:30 8:30 p.m. 1 M17 EN Sgr 18h21’ -16˚11’ 6.0 40’x30’ Omega Nebula 2 M16 EN Ser 18h19’ -13˚47 6.0 17’ by 14’ Ghost Puppet Nebula 3 M10 GC Oph 16h58’ -04˚08’ 6.6 20’ 4 M12 GC Oph 16h48’ -01˚59’ 6.7 16’ 5 M51 Gal CVn 13h30’ 47h05’’ 8.0 13.8’x11.8’ Whirlpool Facing West - 8:30 – 9:00 p.m. 6 M101 GAL UMa 14h03’ 54˚15’ 7.9 24x22.9’ 7 NGC 6572 PN Oph 18h12’ 06˚51’ 7.3 16”x13” Emerald Eye 8 NGC 6426 GC Oph 17h46’ 03˚10’ 11.0 4.2’ 9 NGC 6633 OC Oph 18h28’ 06˚31’ 4.6 20’ Tweedledum 10 IC 4756 OC Ser 18h40’ 05˚28” 4.6 39’ Tweedledee 11 M26 OC Sct 18h46’ -09˚22’ 8.0 7.0’ 12 NGC 6712 GC Sct 18h54’ -08˚41’ 8.1 9.8’ 13 M13 GC Her 16h42’ 36˚25’ 5.8 20’ Great Hercules Cluster 14 NGC 6709 OC Aql 18h52’ 10˚21’ 6.7 14’ Flying Unicorn 15 M71 GC Sge 19h55’ 18˚50’ 8.2 7’ 16 M27 PN Vul 20h00’ 22˚43’ 7.3 8’x6’ Dumbbell Nebula 17 M56 GC Lyr 19h17’ 30˚13 8.3 9’ 18 M57 PN Lyr 18h54’ 33˚03’ 8.8 1.4’x1.1’ Ring Nebula 19 M92 GC Her 17h18’ 43˚07’ 6.44 14’ 20 M72 GC Aqr 20h54’ -12˚32’ 9.2 6’ Facing West - 9 – 10 p.m. -

A Basic Requirement for Studying the Heavens Is Determining Where In

Abasic requirement for studying the heavens is determining where in the sky things are. To specify sky positions, astronomers have developed several coordinate systems. Each uses a coordinate grid projected on to the celestial sphere, in analogy to the geographic coordinate system used on the surface of the Earth. The coordinate systems differ only in their choice of the fundamental plane, which divides the sky into two equal hemispheres along a great circle (the fundamental plane of the geographic system is the Earth's equator) . Each coordinate system is named for its choice of fundamental plane. The equatorial coordinate system is probably the most widely used celestial coordinate system. It is also the one most closely related to the geographic coordinate system, because they use the same fun damental plane and the same poles. The projection of the Earth's equator onto the celestial sphere is called the celestial equator. Similarly, projecting the geographic poles on to the celest ial sphere defines the north and south celestial poles. However, there is an important difference between the equatorial and geographic coordinate systems: the geographic system is fixed to the Earth; it rotates as the Earth does . The equatorial system is fixed to the stars, so it appears to rotate across the sky with the stars, but of course it's really the Earth rotating under the fixed sky. The latitudinal (latitude-like) angle of the equatorial system is called declination (Dec for short) . It measures the angle of an object above or below the celestial equator. The longitud inal angle is called the right ascension (RA for short). -

Astronomy 2008 Index

Astronomy Magazine Article Title Index 10 rising stars of astronomy, 8:60–8:63 1.5 million galaxies revealed, 3:41–3:43 185 million years before the dinosaurs’ demise, did an asteroid nearly end life on Earth?, 4:34–4:39 A Aligned aurorae, 8:27 All about the Veil Nebula, 6:56–6:61 Amateur astronomy’s greatest generation, 8:68–8:71 Amateurs see fireballs from U.S. satellite kill, 7:24 Another Earth, 6:13 Another super-Earth discovered, 9:21 Antares gang, The, 7:18 Antimatter traced, 5:23 Are big-planet systems uncommon?, 10:23 Are super-sized Earths the new frontier?, 11:26–11:31 Are these space rocks from Mercury?, 11:32–11:37 Are we done yet?, 4:14 Are we looking for life in the right places?, 7:28–7:33 Ask the aliens, 3:12 Asteroid sleuths find the dino killer, 1:20 Astro-humiliation, 10:14 Astroimaging over ancient Greece, 12:64–12:69 Astronaut rescue rocket revs up, 11:22 Astronomers spy a giant particle accelerator in the sky, 5:21 Astronomers unearth a star’s death secrets, 10:18 Astronomers witness alien star flip-out, 6:27 Astronomy magazine’s first 35 years, 8:supplement Astronomy’s guide to Go-to telescopes, 10:supplement Auroral storm trigger confirmed, 11:18 B Backstage at Astronomy, 8:76–8:82 Basking in the Sun, 5:16 Biggest planet’s 5 deepest mysteries, The, 1:38–1:43 Binary pulsar test affirms relativity, 10:21 Binocular Telescope snaps first image, 6:21 Black hole sets a record, 2:20 Black holes wind up galaxy arms, 9:19 Brightest starburst galaxy discovered, 12:23 C Calling all space probes, 10:64–10:65 Calling on Cassiopeia, 11:76 Canada to launch new asteroid hunter, 11:19 Canada’s handy robot, 1:24 Cannibal next door, The, 3:38 Capture images of our local star, 4:66–4:67 Cassini confirms Titan lakes, 12:27 Cassini scopes Saturn’s two-toned moon, 1:25 Cassini “tastes” Enceladus’ plumes, 7:26 Cepheus’ fall delights, 10:85 Choose the dome that’s right for you, 5:70–5:71 Clearing the air about seeing vs. -

Global Fitting of Globular Cluster Age Indicators

A&A 456, 1085–1096 (2006) Astronomy DOI: 10.1051/0004-6361:20065133 & c ESO 2006 Astrophysics Global fitting of globular cluster age indicators F. Meissner1 and A. Weiss1 Max-Planck-Institut für Astrophysik, Karl-Schwarzschild-Str. 1, 85748 Garching, Germany e-mail: [meissner;weiss]@mpa-garching.mpg.de Received 3 March 2006 / Accepted 12 June 2006 ABSTRACT Context. Stellar models and the methods for the age determinations of globular clusters are still in need of improvement. Aims. We attempt to obtain a more objective method of age determination based on cluster diagrams, avoiding the introduction of biases due to the preference of one single age indicator. Methods. We compute new stellar evolutionary tracks and derive the dependence of age indicating points along the tracks and isochrone – such as the turn-off or bump location – as a function of age and metallicity. The same critical points are identified in the colour-magnitude diagrams of globular clusters from a homogeneous database. Several age indicators are then fitted simultaneously, and the overall best-fitting isochrone is selected to determine the cluster age. We also determine the goodness-of-fit for different sets of indicators to estimate the confidence level of our results. Results. We find that our isochrones provide no acceptable fit for all age indicators. In particular, the location of the bump and the brightness of the tip of the red giant branch are problematic. On the other hand, the turn-off region is very well reproduced, and restricting the method to indicators depending on it results in trustworthy ages. Using an alternative set of isochrones improves the situation, but neither leads to an acceptable global fit. -

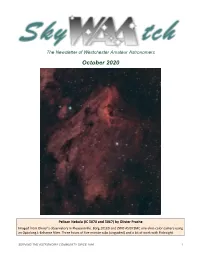

October 2020

The Newsletter of Westchester Amateur Astronomers October 2020 Pelican Nebula (IC 5070 and 5067) by Olivier Prache Imaged from Olivier’s observatory in Pleasantville. Borg 101ED and ZWO ASI071MC one-shot-color camera using an Optolong L-Enhance filter. Three hours of five-minute subs (unguided) and a bit of work with PixInsight. SERVING THE ASTRONOMY COMMUNITY SINCE 1986 1 Westchester Amateur Astronomers SkyWAAtch October 2020 WAA October Meeting WAA November Meeting Friday, October 2 at 7:30 pm Friday, November at 6 7:30 pm On-line via Zoom On-line via Zoom Intelligent Nighttime Lighting: The Many BLACK HOLES: Not so black? Benefits of Dark Skies Willie Yee Charles Fulco Recent years have seen major breakthroughs in the Science educator Charles Fulco will discuss the meth- study of black holes, including the first image of a ods and many benefits of reducing light pollution, black hole from the Event Horizon Telescope and the including energy and tax dollar savings, health bene- detection of black hole collisions with the Laser fits and of course seeing the Milky Way again. Invita- Interferometer Gravitational-wave Observatory. tions and log-in instructions will be sent to WAA Dr. Yee, a NASA Solar System Ambassador and Past members via email. President of the Mid-Hudson Astronomical Association, will review the basic science of black Starway to Heaven holes and the myths surrounding them, and present Ward Pound Ridge Reservation, the recent findings of these projects. Cross River, NY Call: 1-877-456-5778 (toll free) for announcements, Scheduled for Oct 10th (rain/cloud date Oct 17). -

134, December 2007

British Astronomical Association VARIABLE STAR SECTION CIRCULAR No 134, December 2007 Contents AB Andromedae Primary Minima ......................................... inside front cover From the Director ............................................................................................. 1 Recurrent Objects Programme and Long Term Polar Programme News............4 Eclipsing Binary News ..................................................................................... 5 Chart News ...................................................................................................... 7 CE Lyncis ......................................................................................................... 9 New Chart for CE and SV Lyncis ........................................................ 10 SV Lyncis Light Curves 1971-2007 ............................................................... 11 An Introduction to Measuring Variable Stars using a CCD Camera..............13 Cataclysmic Variables-Some Recent Experiences ........................................... 16 The UK Virtual Observatory ......................................................................... 18 A New Infrared Variable in Scutum ................................................................ 22 The Life and Times of Charles Frederick Butterworth, FRAS........................24 A Hard Day’s Night: Day-to-Day Photometry of Vega and Beta Lyrae.........28 Delta Cephei, 2007 ......................................................................................... 33 -

2018 Object List.Pages

Observer’s Challenge Objects for 2018: Our tenth Year! January: NGC 1624 – Nebula + Cluster; Perseus; Mag. 11.8; Size 5′ RA: O4h 40.6m Dec. +50º 28′ 15 cm reveals this nebula faintly as a diffuse glow lying mostly N of mag. 12 star that has two fainter companions E and SE. With 25 cm the nebula remains fairly faint. The cluster is poor, containing only a dozen stars in an L-shaped asterism with the brightest star at the bend. Skiff and Lunginbuhl Observing Handbook and Catalog of Deep-Sky Objects ! " Image provided by Dr. James Dire February: M41 – Open Cluster; Canis Major; Mag. 4.5; Size 39′ RA: 06h 46.1m Dec. -20º 46′ The famous red star at the center of the cluster has a visual magnitude of 6.9 and a K3 spectrum. Mallas The Messier Album A grand view in the Mallas 4-inch refractor, and indeed one of the finest open clusters for very small apertures. The brightest members form a butterfly pattern, but the cluster as a whole is circular, with little concentration. The 4-inch shows the Espin star as plainly reddish. John Mallas The Messier Album Red star near center shows clearly. A lovely site in a 4-inch at 45x. Visible to the unaided eye on a dark, moonless night. James Mullaney, Celestial Harvest M41 has always been one of my favorite deep-sky objects. Over the years, on many nights, I would take a pair of binoculars outside, just to look at this beautiful cluster. However, needing a small telescope to see the famous Espin star. -

SAC's 110 Best of the NGC

SAC's 110 Best of the NGC by Paul Dickson Version: 1.4 | March 26, 1997 Copyright °c 1996, by Paul Dickson. All rights reserved If you purchased this book from Paul Dickson directly, please ignore this form. I already have most of this information. Why Should You Register This Book? Please register your copy of this book. I have done two book, SAC's 110 Best of the NGC and the Messier Logbook. In the works for late 1997 is a four volume set for the Herschel 400. q I am a beginner and I bought this book to get start with deep-sky observing. q I am an intermediate observer. I bought this book to observe these objects again. q I am an advance observer. I bought this book to add to my collect and/or re-observe these objects again. The book I'm registering is: q SAC's 110 Best of the NGC q Messier Logbook q I would like to purchase a copy of Herschel 400 book when it becomes available. Club Name: __________________________________________ Your Name: __________________________________________ Address: ____________________________________________ City: __________________ State: ____ Zip Code: _________ Mail this to: or E-mail it to: Paul Dickson 7714 N 36th Ave [email protected] Phoenix, AZ 85051-6401 After Observing the Messier Catalog, Try this Observing List: SAC's 110 Best of the NGC [email protected] http://www.seds.org/pub/info/newsletters/sacnews/html/sac.110.best.ngc.html SAC's 110 Best of the NGC is an observing list of some of the best objects after those in the Messier Catalog. -

Astronomy Magazine 2011 Index Subject Index

Astronomy Magazine 2011 Index Subject Index A AAVSO (American Association of Variable Star Observers), 6:18, 44–47, 7:58, 10:11 Abell 35 (Sharpless 2-313) (planetary nebula), 10:70 Abell 85 (supernova remnant), 8:70 Abell 1656 (Coma galaxy cluster), 11:56 Abell 1689 (galaxy cluster), 3:23 Abell 2218 (galaxy cluster), 11:68 Abell 2744 (Pandora's Cluster) (galaxy cluster), 10:20 Abell catalog planetary nebulae, 6:50–53 Acheron Fossae (feature on Mars), 11:36 Adirondack Astronomy Retreat, 5:16 Adobe Photoshop software, 6:64 AKATSUKI orbiter, 4:19 AL (Astronomical League), 7:17, 8:50–51 albedo, 8:12 Alexhelios (moon of 216 Kleopatra), 6:18 Altair (star), 9:15 amateur astronomy change in construction of portable telescopes, 1:70–73 discovery of asteroids, 12:56–60 ten tips for, 1:68–69 American Association of Variable Star Observers (AAVSO), 6:18, 44–47, 7:58, 10:11 American Astronomical Society decadal survey recommendations, 7:16 Lancelot M. Berkeley-New York Community Trust Prize for Meritorious Work in Astronomy, 3:19 Andromeda Galaxy (M31) image of, 11:26 stellar disks, 6:19 Antarctica, astronomical research in, 10:44–48 Antennae galaxies (NGC 4038 and NGC 4039), 11:32, 56 antimatter, 8:24–29 Antu Telescope, 11:37 APM 08279+5255 (quasar), 11:18 arcminutes, 10:51 arcseconds, 10:51 Arp 147 (galaxy pair), 6:19 Arp 188 (Tadpole Galaxy), 11:30 Arp 273 (galaxy pair), 11:65 Arp 299 (NGC 3690) (galaxy pair), 10:55–57 ARTEMIS spacecraft, 11:17 asteroid belt, origin of, 8:55 asteroids See also names of specific asteroids amateur discovery of, 12:62–63 -

Globular Cluster Club

Globular Cluster Observing Club Raleigh Astronomy Club Version 1.2 22 June 2007 Introduction Welcome to the Globular Cluster Observing Club! This list is intended to give you an appreciation for the deep-sky objects known as globular clusters. There are 153 known Milky Way Globular Clusters of which the entire list can be found on the seds.org site listed below. To receive your Gold level we will only have you do sixty of them along with one challenge object from a list of three. Challenge objects being the extra-galactic globular Mayall II (G1) located in the Andromeda Galaxy, Palomar 4 in Ursa Major, and Omega Centauri a magnificent southern globular. The first two challenge your scope and viewing ability while Omega Centauri challenges your ability to plan for a southern view. A Silver level is also available and will be within the range of a 4 inch to 8 inch scope depending upon seeing conditions. Many of the objects are found in the Messier, Caldwell, or Herschel catalogs and can springboard you into those clubs. The list is meant for your viewing enrichment and edification of these types of clusters. It is also meant to enhance your viewing skills. You are encouraged to view the clusters with a critical eye toward the cluster’s size, visual magnitude, resolvability, concentration and colors. The Astronomical League’s Globular Clusters Club book “Guide to the Globular Cluster Observing Club” is an excellent resource for this endeavor. You will be asked to either sketch the cluster or give a short description of your visual impression, citing seeing conditions, time, date, cluster’s size, magnitude, resolvability, concentration, and any star colors.