Object in Nature.4 in the Mende

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Côte D'ivoire

CÔTE D’IVOIRE COI Compilation August 2017 United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees Regional Representation for West Africa - RSD Unit UNHCR Côte d’Ivoire UNHCR Regional Representation for West Africa - RSD Unit UNHCR Côte d’Ivoire Côte d’Ivoire COI Compilation August 2017 This report collates country of origin information (COI) on Côte d’Ivoire up to 15 August 2017 on issues of relevance in refugee status determination for Ivorian nationals. The report is based on publicly available information, studies and commentaries. It is illustrative, but is neither exhaustive of information available in the public domain nor intended to be a general report on human-rights conditions. The report is not conclusive as to the merits of any individual refugee claim. All sources are cited and fully referenced. Users should refer to the full text of documents cited and assess the credibility, relevance and timeliness of source material with reference to the specific research concerns arising from individual applications. UNHCR Regional Representation for West Africa Immeuble FAALO Almadies, Route du King Fahd Palace Dakar, Senegal - BP 3125 Phone: +221 33 867 62 07 Kora.unhcr.org - www.unhcr.org Table of Contents List of Abbreviations .............................................................................................................. 4 1 General Information ....................................................................................................... 5 1.1 Historical background ............................................................................................ -

Roberta Hildagard Quander

Roberta Hildagard Quander Sunrise: February 10, 1924 Sunset: May 4, 2020 Friday, May 15, 2020 at 2:00 P.M. Graveside Service Bethel Cemetery Old Town , Alexandria, VA Order of Service Opening Prayer Rev. Marla C. Hawkins Scripture Reading Rev. Edward Y. Jackson Condolences Rev. Dr. Howard-John Wesley, Pastor Reflections of the “Queen” Pastor Wesley Comital Ceremony Pastor Wesley Benediction Pastor Wesley A TREE HAS FALLEN Blessed is the woman that walketh not in the counsel of the ungodly, nor standeth in the way of sinners, nor sitteth in the seat of the scornful. But her delight is in the law of the LORD; and in his law doth she meditate day and night. And she shall be like a tree planted by the rivers of water, that bringeth forth its fruit in its season; her leaf also shall not wither; and whatsoever she doeth shall prosper. Roberta Hildagard Quander was born on February 10, 1924 to Robert H. Quander and Sadie Chinn Quander. Her parents had been married at Alfred Street in February 1911 by Rev. Alexander Truatt. Roberta was the youngest of four children born to this couple, including Grayce Elaine, Emmett and another brother (stillborn). Roberta’s sister Grayce had served as Treasurer at Alfred Street and upon her death in 1967, the church honored Grayce with a special cancer fund taken each year. Roberta accepted Christ at an early and joined Alfred Street, her family church, in 1928 as a four-year old. Her family had been members of Alfred Street since 1807 when Mariah Quander joined. -

University of Cincinnati

UNIVERSITY OF CINCINNATI Date:_December 13, 2006_ I, James Michael Rhyne______________________________________, hereby submit this work as part of the requirements for the degree of: Doctor of Philosophy in: History It is entitled: Rehearsal for Redemption: The Politics of Post-Emancipation Violence in Kentucky’s Bluegrass Region This work and its defense approved by: Chair: _Wayne K. Durrill_____________ _Christopher Phillips_________ _Wendy Kline__________________ _Linda Przybyszewski__________ Rehearsal for Redemption: The Politics of Post-Emancipation Violence in Kentucky’s Bluegrass Region A Dissertation submitted to the Division of Research and Advanced Studies of the University of Cincinnati in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy (Ph.D.) in the Department of History of the College of Arts and Sciences 2006 By James Michael Rhyne M.A., Western Carolina University, 1997 M-Div., Southeastern Baptist Theological Seminary, 1989 B.A., Wake Forest University, 1982 Committee Chair: Professor Wayne K. Durrill Abstract Rehearsal for Redemption: The Politics of Post-Emancipation Violence in Kentucky’s Bluegrass Region By James Michael Rhyne In the late antebellum period, changing economic and social realities fostered conflicts among Kentuckians as tension built over a number of issues, especially the future of slavery. Local clashes matured into widespread, violent confrontations during the Civil War, as an ugly guerrilla war raged through much of the state. Additionally, African Americans engaged in a wartime contest over the meaning of freedom. Nowhere were these interconnected conflicts more clearly evidenced than in the Bluegrass Region. Though Kentucky had never seceded, the Freedmen’s Bureau established a branch in the Commonwealth after the war. -

TRC of Liberia Final Report Volum Ii

REPUBLIC OF LIBERIA FINAL REPORT VOLUME II: CONSOLIDATED FINAL REPORT This volume constitutes the final and complete report of the TRC of Liberia containing findings, determinations and recommendations to the government and people of Liberia Volume II: Consolidated Final Report Table of Contents List of Abbreviations <<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<............. i Acknowledgements <<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<... iii Final Statement from the Commission <<<<<<<<<<<<<<<............... v Quotations <<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<. 1 1.0 Executive Summary <<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<< 2 1.1 Mandate of the TRC <<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<< 2 1.2 Background of the Founding of Liberia <<<<<<<<<<<<<<<... 3 1.3 History of the Conflict <<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<................ 4 1.4 Findings and Determinations <<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<< 6 1.5 Recommendations <<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<... 12 1.5.1 To the People of Liberia <<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<. 12 1.5.2 To the Government of Liberia <<<<<<<<<<. <<<<<<. 12 1.5.3 To the International Community <<<<<<<<<<<<<<<. 13 2.0 Introduction <<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<. 14 2.1 The Beginning <<................................................................................................... 14 2.2 Profile of Commissioners of the TRC of Liberia <<<<<<<<<<<<.. 14 2.3 Profile of International Technical Advisory Committee <<<<<<<<<. 18 2.4 Secretariat and Specialized Staff <<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<. 20 2.5 Commissioners, Specialists, Senior Staff, and Administration <<<<<<.. 21 2.5.1 Commissioners <<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<. 22 2.5.2 International Technical Advisory -

H.Doc. 108-224 Black Americans in Congress 1870-2007

FORMER MEMBERS H 1870–1887 ������������������������������������������������������������������������ Robert Smalls 1839 –1915 UNITED STATES REPRESENTATIVE H 1875–1879; 1882–1883; 1884–1887 REPUBLICAN FROM SOUTH CAROLINA n escaped slave and a Civil War hero, Robert Smalls publication of his name and former enslaved status in A served five terms in the U.S. House, representing northern propaganda proved demoralizing for the South.7 a South Carolina district described as a “black paradise” Smalls spent the remainder of the war balancing his role because of its abundant political opportunities for as a spokesperson for African Americans with his service freedmen.1 Overcoming the state Democratic Party’s in the Union Armed Forces. Piloting both the Planter, repeated attempts to remove that “blemish” from its goal which was re-outfitted as a troop transport, and later the of white supremacy, Smalls endured violent elections and a ironclad Keokuk, Smalls used his intimate knowledge of the short jail term to achieve internal improvements for coastal South Carolina Sea Islands to advance the Union military South Carolina and to fight for his black constituents in the campaign in nearly 17 engagements.8 face of growing disfranchisement. “My race needs no special Smalls’s public career began during the war. He joined defense, for the past history of them in this country proves free black delegates to the 1864 Republican National them to be equal of any people anywhere,” Smalls asserted. Convention, the first of seven total conventions he “All they need is an equal chance in the battle of life.”2 attended as a delegate.9 While awaiting repairs to the Robert Smalls was born a slave on April 5, 1839, in Planter, Smalls was removed from an all-white streetcar Beaufort, South Carolina. -

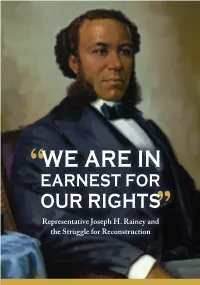

"We Are in Earnest for Our Rights": Representative

Representative Joseph H. Rainey and the Struggle for Reconstruction On the cover: This portrait of Joseph Hayne Rainey, the f irst African American elected to the U.S. House of Representatives, was unveiled in 2005. It hangs in the Capitol. Joseph Hayne Rainey, Simmie Knox, 2004, Collection of the U.S. House of Representatives Representative Joseph H. Rainey and the Struggle for Reconstruction September 2020 2 | “We Are in Earnest for Our Rights” n April 29, 1874, Joseph Hayne Rainey captivity and abolitionists such as Frederick of South Carolina arrived at the U.S. Douglass had long envisioned a day when OCapitol for the start of another legislative day. African Americans would wield power in the Born into slavery, Rainey had become the f irst halls of government. In fact, in 1855, almost African-American Member of the U.S. House 20 years before Rainey presided over the of Representatives when he was sworn in on House, John Mercer Langston—a future U.S. December 12, 1870. In less than four years, he Representative from Virginia—became one of had established himself as a skilled orator and the f irst Black of f iceholders in the United States respected colleague in Congress. upon his election as clerk of Brownhelm, Ohio. Rainey was dressed in a f ine suit and a blue silk But the fact remains that as a Black man in South tie as he took his seat in the back of the chamber Carolina, Joseph Rainey’s trailblazing career in to prepare for the upcoming debate on a American politics was an impossibility before the government funding bill. -

Guide to Gwens Databases

THE LOUISIANA SLAVE DATABASE AND THE LOUISIANA FREE DATABASE: 1719-1820 1 By Gwendolyn Midlo Hall This is a description of and user's guide to these databases. Their usefulness in historical interpretation will be demonstrated in several forthcoming publications by the author including several articles in preparation and in press and in her book, The African Diaspora in the Americas: Regions, Ethnicities, and Cultures (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, forthcoming 2000). These databases were created almost entirely from original, manuscript documents located in courthouses and historical archives throughout the State of Louisiana. The project lasted 15 years but was funded for only five of these years. Some records were entered from original manuscript documents housed in archives in France, in Spain, and in Cuba and at the University of Texas in Austin as well. Some were entered from published books and journals. Some of the Atlantic slave trade records were entered from the Harvard Dubois Center Atlantic Slave Trade Dataset. Information for a few records was supplied from unpublished research of other scholars. 2 Each record represents an individual slave who was described in these documents. Slaves were listed, and descriptions of them were recorded in documents in greater or lesser detail when an estate of a deceased person who owned at least one slave was inventoried, when slaves were bought and sold, when they were listed in a will or in a marriage contract, when they were mortgaged or seized for debt or because of the criminal activities of the master, when a runaway slave was reported missing, or when slaves, mainly recaptured runaways, testified in court. -

African Reflections on the American Landscape

National Park Service U.S. Department of the Interior National Center for Cultural Resources African Reflections on the American Landscape IDENTIFYING AND INTERPRETING AFRICANISMS Cover: Moving clockwise starting at the top left, the illustrations in the cover collage include: a photo of Caroline Atwater sweeping her yard in Orange County, NC; an orthographic drawing of the African Baptist Society Church in Nantucket, MA; the creole quarters at Laurel Valley Sugar Plantation in Thibodaux, LA; an outline of Africa from the African Diaspora Map; shotgun houses at Laurel Valley Sugar Plantation; details from the African Diaspora Map; a drawing of the creole quarters at Laurel Valley Sugar Plantation; a photo of a banjo and an African fiddle. Cover art courtesy of Ann Stephens, Cox and Associates, Inc. Credits for the illustrations are listed in the publication. This publication was produced under a cooperative agreement between the National Park Service and the National Conference of State Historic Preservation Officers. African Reflections on the American Landscape IDENTIFYING AND INTERPRETING AFRICANISMS Brian D. Joyner Office of Diversity and Special Projects National Center for Cultural Resources National Park Service U.S. Department of the Interior 2003 Ta b le of Contents Executive Summary....................................................iv Acknowledgments .....................................................vi Chapter 1 Africa in America: An Introduction...........................1 What are Africanisms? ......................................2 -

The 19Th Century Jihads in West Africa

THE 19TH CENTURY JIHADS IN WEST AFRICA A Jihad is a holy defensive war waged by Muslim reformers against injustices in the society, aimed at protecting the wronged and oppressed people together with their property and at the same time, spreading, purifying and strengthening Islam. In the Nineteenth Century, West Africa saw a wave of Jihads; however, three were more profound: 1. The Jihads that broke out in Hausaland in 1804 under the leadership of Uthman Dan Fodio. These took place in Sokoto area; and thus came to be known as the Sokoto Jihads. 2. In 1818, another Jihad was conducted in Massina under the headship of Seku (Sehu) Ahmadu. These came to be known as the Massina Jihads. 3. In Futa–Jallon and Futa–toto, another Jihadist called Al-Hajj Umar carried out a Jihad in 1851. This was known as the Tokolor or Tijjan Jihad. All these Jihads were led by members of the Fulani Muslims and carried out by people of Fulani origin; as such, the Jihads came to be known as the Fulani Jihads. CAUSES OF THE 19TH CENTURY JIHAD MOVEMENTS IN WEST AFRICA. Question: Account for the outbreak of the 19th Century Jihad Movement in West Africa. Although the Nineteenth Century Jihads were religious movements, they had a mixture of political, economic and intellectual causes; and a number of factors accounted for their outbreak in West Africa. 1. The 19th Century Jihads aimed at spreading Islam to the people who had not been converted to it. There were areas which had not been touched by Islam such as Mossi, Nupe, Borgu and Adamawa. -

The Inner Workings of Slavery Ava I

__________________________________________________________________ The Inner Workings of Slavery Ava I. Gillespie Ava Gillespie is a h istory major from Tonica, Illinois. She wrote her paper for Historical Research Writing, HIS 2500, with Dr. Bonnie Laughlin - Shultz. ______________________________________________________________________________ I suffered much more during the second winter than I did during the first. My limbs were benumbed by inactions, and the cold filled them with cramp. I had a very painful sensation of coldness in my head; even my face and tongue stiffened, and I lost the power of speech. Of course it was impossible, under the circumstances, to summon any physician. My brother William came and did all he could for me. Unc le Phillip also watched tenderly over me; and poor grandmother crept up and down to inquire whether there was any signs of returning life. I was restored to consciousness by the dashing of cold water in my face, and found myself leaning against my brother’ s arm, while he bent over me with streaming eyes. He afterwards told me he thought I was dying, for I had been in an unconscious state sixteen hours. I next beca me delirious, and was in great danger of betraying myself and my friends. To prevent this, they stupefied me with drugs. I remained in bed six weeks, weary in body and sick at heart…I asked why the curse of slavery was permitted to exist, and why I had been so persecuted and wronged from youth upward. These things took the shape of mystery, which is to this day not so clear to my soul as I trust it will be hereafter. -

Extensions of Remarks

8614 EXTENSIONS OF REMARKS April 10, 1984 EXTENSIONS OF REMARKS TEACHER OF THE YEAR LEADS schools, the loss of teachers, the firing of In 1981, it was decided to expand the pilot THE WAY one superintendent and the hiring of an project to other schools in the country. other. Budget cuts left little money for Junior League volunteers, as well as the salary increases or improving school activi Chamber of Commerce, again went to work, HON. GENE SNYDER ties. School morale sank, and the negative this time at Fairdale and Iroquois High OF KENTUCKY image of the school system was pervasive. Schools. New projects continue to be devel IN THE HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES Many saw the public school system as a fail oped. ure. Tuesday, April 10, 1984 As a direct outgrowth of the Schools-Busi In 1977, the education arm of the Junior ness Project's involvement in computer edu e Mr. SNYDER. Mr. Speaker, for League, of which Mrs. Sherleen Sisney was cation, the Junior League of Louisville re sometime now we have all been talking a dedicated member, felt something should cently announced a "partnership" with the about what we need to do to improve be done. So did many others in the commu community's Westport Middle School. our Nation's school system so that it nity including the Chamber of Commerce. A Under the terms of the partnership, the can more adequately prepare our League committee, chaired by Mrs. Sisney, inner city school will receive a $75,000 grant felt there was no alternative other than for and volunteer support to bring computer young people to meet the challenge of the business community to step in and help. -

Bunce Island: a British Slave Castle in Sierra Leone

BUNCE ISLAND A BRITISH SLAVE CASTLE IN SIERRA LEONE HISTORICAL SUMMARY By Joseph Opala James Madison University Harrisonburg, Virginia (USA) This essay appears as Appendix B in Bunce Island Cultural Resource Assessment and Management Plan By Christopher DeCorse Prepared on behalf of the United States Embassy, Sierra Leone and Submitted to the Sierra Leone Monuments and Relics Commission November, 2007 INTRODUCTION Bunce Island is a slave castle located in the West African nation of Sierra Leone. Slave castles were commercial forts operated by European merchants during the period of the Atlantic slave trade. They have been called “warehouses of humanity.” Behind their high protective walls, European slave traders purchased Africans, imprisoned them, and loaded them aboard the slave ships that took them on the middle passage to America. Today, there were about 40 major slave castles located along the 2,000 miles of coastline stretching between Mauritania in the north and Benin in the south. British slave traders operated on Bunce Island from about 1670 to 1807, exiling about 30,000 Africans to slavery in the West Indies and North America. While most of Bunce Island’s captives were taken to sugar plantations in the Caribbean Basin, a substantial minority went to Britain’s North American Colonies, and especially South Carolina and Georgia. Given the fact that only about 4% of the African captives transported during the period of the Atlantic slave trade went to North America, Bunce Island’s strong link to that region makes it unique among the West African slave castles. Bunce Island’s commercial ties to North America resulted, as we shall see, in this particular castle and its personnel being linked to important economic, political, and military developments on that continent.