The Surprising Truth About Fake Art and How to Avoid Being Scammed

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Report of the Commission on Institutional History and Community

Report of the Commission on Institutional History and Community Washington and Lee University May 2, 2018 1 Table of Contents Introduction …………………………………………………………………………...3 Part I: Methodology: Outreach and Response……………………………………...6 Part II: Reflecting on the Legacy of the Past……………………………………….10 Part III: Physical Campus……………………………………………………………28 Conclusion…………………………………………………………………………….45 Appendix A: Commission Member Biographies………………………………….46 Appendix B: Outreach………………………………………………………………..51 Appendix C: Origins and Development of Washington and Lee………………..63 Appendix D: Recommendations………………………………………………….....95 Appendix E: Portraits on Display on Campus……………………………………107 Appendix F: List of Building Names, Markers and Memorial Sites……………116 2 INTRODUCTION Washington and Lee University President Will Dudley formed the Commission on Institutional History and Community in the aftermath of events that occurred in August 2017 in Charlottesville, Virginia. In February 2017, the Charlottesville City Council had voted to remove a statue of Robert E. Lee from a public park, and Unite the Right members demonstrated against that decision on August 12. Counter- demonstrators marched through Charlottesville in opposition to the beliefs of Unite the Right. One participant was accused of driving a car into a crowd and killing 32-year-old Heather Heyer. The country was horrified. A national discussion on the use of Confederate symbols and monuments was already in progress after Dylann Roof murdered nine black church members at Emanuel African Methodist Episcopal (AME) Church in Charleston, South Carolina, on June 17, 2015. Photos of Roof posing with the Confederate flag were spread across the internet. Discussion of these events, including the origins of Confederate objects and images and their appropriation by groups today, was a backdrop for President Dudley’s appointment of the commission on Aug. -

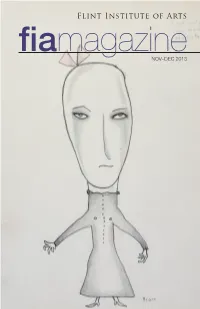

2013 Issue #5

Flint Institute of Arts fiamagazineNOV–DEC 2013 Website www.flintarts.org Mailing Address 1120 E. Kearsley St. contents Flint, MI 48503 Telephone 810.234.1695 from the director 2 Fax 810.234.1692 Office Hours Mon–Fri, 9a–5p exhibitions 3–4 Gallery Hours Mon–Wed & Fri, 12p–5p Thu, 12p–9p video gallery 5 Sat, 10a–5p Sun, 1p–5p art on loan 6 Closed on major holidays Theater Hours Fri & Sat, 7:30p featured acquisition 7 Sun, 2p acquisitions 8 Museum Shop 810.234.1695 Mon–Wed, Fri & Sat, 10a–5p Thu, 10a–9p films 9–10 Sun, 1p–5p calendar 11 The Palette 810.249.0593 Mon–Wed & Fri, 9a–5p Thu, 9a–9p news & programs 12–17 Sat, 10a–5p Sun, 1p–5p art school 18–19 The Museum Shop and education 20–23 The Palette are open late for select special events. membership 24–27 Founders Art Sales 810.237.7321 & Rental Gallery Tue–Sat, 10a–5p contributions 28–30 Sun, 1p–5p or by appointment art sales & rental gallery 31 Admission to FIA members .............FREE founders travel 32 Temporary Adults .........................$7.00 Exhibitions 12 & under .................FREE museum shop 33 Students w/ ID ...........$5.00 Senior citizens 62+ ....$5.00 cover image From the exhibition Beatrice Wood: Mama of Dada Beatrice Wood American, 1893–1998 I Eat Only Soy Bean Products pencil, color pencil on paper, 1933 12.0625 x 9 inches Gift of Francis M. Naumann Fine Art, LLC, 2011.370 FROM THE DIRECTOR 2 I never tire of walking through the sacred or profane, that further FIA’s permanent collection galleries enhances the action in each scene. -

Summer 2013 in “John Singer Sargent Watercolors,” Brooklyn Museum, NY

museumVIEWS A quarterly newsletter for small and mid-sized art museums John Singer Sargent, Simplon Pass: Reading, c.1911. Opaque and translucent watercolor and wax resist with graphite underdrawing. Summer 2013 In “John Singer Sargent Watercolors,” Brooklyn Museum, NY 1 museumVIEWS Features Summer 2013 Page 3 • Biennale • From the AAM Page 4 • Notes about an Artist: Left: Reference photo for Norman Rockwell’s Breakfast Table Politcal Arguement Above: Norman Rockwell, Breakfast Table Politcal Arguement, Ellsworth Kelly (detail) 1948. Illustration for The Saturday Evening Post. Both in “Norman Rockwell: Behind the Camera,” McNay Art Museum, TX • Building an Emergency Plan Page 5 • African-American Art Hits the Nation’s Museums • Numbers Game: Some Museum Statistics • Research Results in Surprise Findings Page 6 • Baruch and Rubin Pair up for Conference Pages 7 • Tips for Travel Off the Beaten Track Page 8-11 • newsbriefs Pages 12 • Textiles Take Center Stage in Denver Pages 13-19 • summerVIEWS Ridley Howard, Blues and Pink (detail), 2012. Oil on linen. In “Ridley Howard,” Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, MA Jeffrey Gibson, Much Stronger Than You Know, 2013. Acrylic and oil paint on deer hide stretched over wood panel. In “Jeffrey Gibson: Said the Pigeon museumVIEWS to the Squirrel,” National Academy Museum, NY Editor: Lila Sherman Publisher: Museum Views, Ltd. 2 Peter Cooper Road, New York, NY 10010 Phone: 212.677.3415 FAX: 212.533.5227 Email: [email protected] On the web: www.museumviews.org MuseumVIEWS is supported by grants from the Horace W. Goldsmith Foundation and Bloomberg. MuseumVIEWS is published 4 times a year: Winter (Jan. -

Encyklopédia Kresťanského Umenia

Marie Žúborová - Němcová: Encyklopédia kresťanského umenia americká architektúra - pozri chicagská škola, prériová škola, organická architektúra, Queen Anne style v Spojených štátoch, Usonia americká ilustrácia - pozri zlatý vek americkej ilustrácie americká retuš - retuš americká americká ruleta/americké zrnidlo - oceľové ozubené koliesko na zahnutej ose, užívané na zazrnenie plochy kovového štočku; plocha spracovaná do čiarok, pravidelných aj nepravidelných zŕn nedosahuje kvality plochy spracovanej kolískou americká scéna - american scene americké architektky - pozri americkí architekti http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Category:American_women_architects americké sklo - secesné výrobky z krištáľového skla od Luisa Comforta Tiffaniho, ktoré silno ovplyvnili európsku sklársku produkciu; vyznačujú sa jemnou farebnou škálou a novými tvarmi americké litografky - pozri americkí litografi http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Category:American_women_printmakers A Anne Appleby Dotty Atti Alicia Austin B Peggy Bacon Belle Baranceanu Santa Barraza Jennifer Bartlett Virginia Berresford Camille Billops Isabel Bishop Lee Bontec Kate Borcherding Hilary Brace C Allie máj "AM" Carpenter Mary Cassatt Vija Celminš Irene Chan Amelia R. Coats Susan Crile D Janet Doubí Erickson Dale DeArmond Margaret Dobson E Ronnie Elliott Maria Epes F Frances Foy Juliette mája Fraser Edith Frohock G Wanda Gag Esther Gentle Heslo AMERICKÁ - AMES Strana 1 z 152 Marie Žúborová - Němcová: Encyklopédia kresťanského umenia Charlotte Gilbertson Anne Goldthwaite Blanche Grambs H Ellen Day -

Records Regarding Artwork Acquired by the Smithsonian Institution (SI) During 2011

Description of document: Records regarding artwork acquired by the Smithsonian Institution (SI) during 2011 Request date: 17-September-2011 Released date: 29-November-2011 Posted date: 26-October-2015 Source of document: The Smithsonian Institution MRC 524 PO Box 37012 Washington DC 20013-7012 Fax: 202-633-7079 The governmentattic.org web site (“the site”) is noncommercial and free to the public. The site and materials made available on the site, such as this file, are for reference only. The governmentattic.org web site and its principals have made every effort to make this information as complete and as accurate as possible, however, there may be mistakes and omissions, both typographical and in content. The governmentattic.org web site and its principals shall have neither liability nor responsibility to any person or entity with respect to any loss or damage caused, or alleged to have been caused, directly or indirectly, by the information provided on the governmentattic.org web site or in this file. The public records published on the site were obtained from government agencies using proper legal channels. Each document is identified as to the source. Any concerns about the contents of the site should be directed to the agency originating the document in question. GovernmentAttic.org is not responsible for the contents of documents published on the website. From: "Murphy, Tim" <[email protected]> Date: Tue, 29 Nov 2011 15:10:51 -0500 Cc: "Fancher-Bishop, Annette" <[email protected]> Subject: A Response to Your Request for Smithsonian Institution Records VIA ELECTRONIC MAIL November 29, 2011 Re: Your Request for Smithsonian Institution Records. -

Annual Year Dates Theme Painting Acquired Artists Exhbited Curator Location Media Used Misc

Annual Year Dates Theme Painting acquired Artists Exhbited Curator Location Media Used Misc. Notes 1st 1911 Paintings by French and American Artists Loaned by Robert C Ogden of New York 2nd 1912 (1913 by LS) Paintings by French and American Artists Loaned by Robert C Ogden of New York 3rd 1913 (1914 by LS) 1914/ (1915 from Lake Bennet, Alaska, Louise Jordan 4th Alaskan Landscapes by Leonard Davis Leonard Davis Purchase made possible by the admission fees to 4th annual LS) M1915.1 Smith Fifth Exhbition Oil Paintings at Randolph-Macon Groge Bellows, Louis Betts, Irving E. Couse, Bruce Crane, Frank V. DuMonds, Ben Foster, Daniel Garber, Lillian Woman's College: Paintings by Contemporary Matilde Genth, Edmund Greacen, Haley Lever, Robert Henri, Clara MacChesney, William Ritschel, Walter Elmer March 9- 5th 1916 American Artists, Loaned by the National Art Club Schofield, Henry B. Snell, Gardner Symons, Douglas Folk, Guy C. Wiggins, Frederick J. Waugh, Frederick Ballard Loaned by the National Arts Club of New York from their permanent collection by Life Members. April 8 of New York from Their Permanent Collection by Williams Life Members Exhibition by:Jules Guerin, Childe Hassam, Robert Louise Jordan From catalogue: "Randolph-Macon feels that its annual Exhibition forms a valuable part of the cultural opportunities of college 6th 1917 March 2-28 Jules Guerin, Childe Hassam, Robert Henri, J. Alden Weir Henri, J. Alden Weir Smith life." Juliu Paul Junghanns, Sir Alfred East, Henri Martin, Jacques Emile Blanche, Emond Aman-Jean, Ludwig Dill, Louise Jordan 7th 1918 International Exhbition George Sauter, George Spencer Watson, Charles Cottet, Gaston LaTouche, S.J. -

Island REPORTER SANI8EL a HO Caf>TIVA

island REPORTER SANI8EL A HO CAf>TIVA. FLORIDA Rene Miville off Captiva is a leader in the revival of downtown Fort Myers PHOTO BY CRAIG GARRET!' ALSOMSDETODAY ALSOINSIDETODAY ALSOMSOETODAY ALSOMSDETODAY Shell Shocked ................................................4 C a le n d a r.............. .46 Living Sanibel.............................................13 Island Hom e ................................................. 14 Captiva Current 43 Poetic License .............................................39 Island Reporter......................................15-38 Classifieds . 49 What’s Blooming ....................................... 39 SSMU03 jaiuoisnQ lEjiuapisau This Week's ...1674 Bunting Lane 3/2 Old Florida Style eezs# i!Lujad Featured Property Southern Exposure Pool Home Id ‘SU3AIAI Id www. 674BuntingLane.roni aivd for Sale... 1 a o v is o d sn $569,000 Call Eric Pfeifer a is a is u d Pfeifer Realty Group 239-472-0004 Recreation center recognizes camp counselors Page Page 2 The Sanibel Recreation Center also been a great way to meet other camp is being able to help the chil a doctorate in psychology and M would like to recognize this sum volunteers his age and make dren have fun and make memories become either a psychologist or a mer’s Counselors In Training friends. De Groote enjoys playing at camp. behavioral analyst. O’Brien’s (CITs): Othello De Groote, Sofia tennis and soccer in his spare time Anna Kjoller will be a tenth favorite thing about being a CIT is Halbisen, Anna Kjoller, Michael and aspires to be a doctor. grader at Bishop Verot High engaging with the kids and being O’Brien, Nick Smith, Katherine Sofia Halbisen will be entering School, where she is a part of the involved in their day to day activi Strange and Madi Weigel. -

Jean-Noel Archive.Qxp.Qxp

THE JEAN-NOËL HERLIN ARCHIVE PROJECT Jean-Noël Herlin New York City 2005 Table of Contents Introduction i Individual artists and performers, collaborators, and groups 1 Individual artists and performers, collaborators, and groups. Selections A-D 77 Group events and clippings by title 109 Group events without title / Organizations 129 Periodicals 149 Introduction In the context of my activity as an antiquarian bookseller I began in 1973 to acquire exhibition invitations/announcements and poster/mailers on painting, sculpture, drawing and prints, performance, and video. I was motivated by the quasi-neglect in which these ephemeral primary sources in art history were held by American commercial channels, and the project to create a database towards the bibliographic recording of largely ignored material. Documentary value and thinness were my only criteria of inclusion. Sources of material were random. Material was acquired as funds could be diverted from my bookshop. With the rapid increase in number and diversity of sources, my initial concept evolved from a documentary to a study archive project on international visual and performing arts, reflecting the appearance of new media and art making/producing practices, globalization, the blurring of lines between high and low, and the challenges to originality and quality as authoritative criteria of classification and appreciation. In addition to painting, sculpture, drawing and prints, performance and video, the Jean-Noël Herlin Archive Project includes material on architecture, design, caricature, comics, animation, mail art, music, dance, theater, photography, film, textiles and the arts of fire. It also contains material on galleries, collectors, museums, foundations, alternative spaces, and clubs. -

2018 Bulletin

2018 Bulletin Table of Contents 5 Director’s Message 6 Austin by Ellsworth Kelly 8 Exhibitions 16 Public Programs 24 Community Engagement 26 Family Programs 28 Community Programs 34 School Programs 36 University Engagement 46 The Julia Matthews Wilkinson Center for Prints and Drawings 47 Publications 48 Acquisitions 100 Exhibition Loans 102 Finances 103 Donor Listing 2018 BLANTON BULLETIN Blanton National Leadership Board 2018-2019 Janet Allen, Chair BLANTON ATTENDANCE Five-Year Growth Janet and Wilson Allen FY2014 137,988 Leslie and Jack Blanton, Jr. Suzanne Deal Booth FY2015 136,657 Sarah and Ernest Butler FY2016 149,755 Michael Chesser Mary McDermott Cook FY2017 157,619 Alessandra Manning-Dolnier and Kurt Dolnier FY2018 203,561 Tamara and Charles Dorrance Sally and Tom Dunning 0 50,000 100,000 150,000 200,000 250,000 Kelley and Pat Frost Stephanie and David Goodman Anthony Grant Shannon and Mark Hart Eric Herschmann Stacy and Joel Hock BLANTON VISITORS BY TYPE FY2018 (September 2017–August 2018) Sonja and Joe Holt Kenny and Susie Jastrow Marilyn D. Johnson Jeanne and Michael Klein Jenny and Trey Laird 31% 42% Cornelia and Meredith Long Clayton and Andrew Maebius Suzanne McFayden 5% Fredericka and David Middleton 22% Elle Moody Lora Reynolds and Quincy Lee Adults (including members, UT faculty, and staff) 42% Richard Shiff Eliza and Stuart W. Stedman UT Students 22% Judy and Charles Tate Students from other Colleges and Universities 5% Marilynn and Carl Thoma Youth (1– 21) 31% Bridget and Patrick Wade Jessica and Jimmy Younger 4 —— National Leadership Board 2018 BLANTON BULLETIN Director’s Message It has been a historic year for the Blanton, and we are excited to share some of the major milestones with you. -

Style in My Mortal Enemy by Janah R

Secreted Behind Closed Doors: Rethinking Cather‘s Adultery Theme and ―Unfurnished‖ Style in My Mortal Enemy by Janah R. Adams June, 2011 Director of Thesis or Dissertation: Dr. Richard Taylor Major Department: English In recent years, My Mortal Enemy (1926) has been virtually ignored in Cather scholarship. I place the novel in its literary and critical context by building on information from the critical reception and recent scholarship on Cather's work to see how My Mortal Enemy fits into the expectations of Cather's writing at the time. A rejection of Cather's changing style at the time of the novels‘ reception and in more modern criticism has led to a rather narrow assessment of the novels‘ more ambiguous scenes and an overwhelming hostility toward its protagonist, obscuring the existence of other, more positive interpretations. I provide a close study of the novels‘ ambiguous scenes in relation to Cather‘s own discussion of her ―unfurnished‖ style, and explore how critics may have misread these scenes and how we might utilize a new approach, one that takes into consideration Cather's interest and relation to the visual art scene of the time, to rethink assumptions about the novel and about its protagonist. I use Cather's 1923 novel A Lost Lady and the criticism that surrounded it to rethink My Mortal Enemy and provide a new way of reading the novel, solidifying My Mortal Enemy’s place in the Cather canon and strengthening its value to the study of her life and works. By suggesting a fresh approach to the novel, I encourage readers of Cather‘s work to return to My Mortal Enemy to see what they too may have overlooked or misread in their first reading, in context of the novel itself, other novels by Cather, and the spirit of the time in which Cather lived and worked. -

Table of Contents

Volume 18, Number 1 ~ Winter 2014 Table of Contents Contents John Money and Graduate Student Research Awardees Grants support student research in Anthropology, Sociology, Human Development, and Gender Studies. Women, Immunity and Sexual Health Study New study examines sexual activity & immune response across the menstrual cycle. Spring Exhibits in the Kinsey Gallery Beauty and the Beast, Flora, and The Right to Read. Kinsey Reporter App New surveys on pornography, and on Valentine expectations. New Faces at the Institute Welcome Tierney Lorenz, Krista Milich & Gene McClain. Helen Fisher Donates Her Archives Noted anthropologist reflects on leaving one's life's work to The Kinsey Institute. Research News Singles in America, talking to children about consent, Kinsey Reporter. Plus: new posts on 'choking games,' porn addiction labels, and more online at KinseyConfidential.com Keep up with The Kinsey Institute™ on Facebook, Twitter, and YouTube The mission of The Kinsey Institute is to promote interdisciplinary research and scholarship in the fields of human sexuality, gender, and reproduction. The Institute was founded in 1947 by renowned sex researcher Alfred Kinsey. Today, the Institute has two components, an Indiana University research institute and a not-for-profit corporation, which owns and manages the Institute's research data and archives, collections, and databases. John Money and Graduate Student Research Awardees We are pleased to announce the 2014 awardees for the John Money Fellowship and the Kinsey Institute Student Research Grants. John Money Fellowship for Scholars of Sexology The John Money Fellowship for Scholars of Sexology was established in 2002 by Dr. John Money, and first awarded in 2009. -

Art Dealer Is Arrested on Charges of Selling Fake De Kooning Artworks

AiA Art News-service Art Dealer Is Arrested on Charges of Selling Fake De Kooning Artworks Brian Boucher, Thursday, February 4, 2016 Eric Ian Hornak Spoutz lecturing at the Washington County museum of Fine Arts in 2013. Photo: Natasha M. Spoutz, via Wikimedia. A Michigan man with several aliases has been arrested on charges of selling forged works by Abstract Expressionist masters. Eric Ian Hornak Spoutz, 32, who also reportedly used the names Robert Chad Smith, John Goodman, and James Sinclair, allegedly forged paper trails to substantiate provenance for dozens of artworks by Willem de Kooning,Joan Mitchell, and others. The arrest happens to come amid an epic fraud trial involving numerous forged paintings, also by Abstract Expressionists, that New York gallery Knoedler & Co. sold for many millions of dollars. Preet Bharara, US Attorney General for the Southern District of New York, and the FBI's Diego Rodriguez announced Spoutz's arrest on Wednesday. Bharara has charged Spoutz with wire fraud, which could send him to prison for twenty years . The arrest concludes an investigation that's been ongoing since 2014. Spoutz allegedly sold some works via a Connecticut auction house on eBay. According to the complaint, the house allegedly sold two pastels, purportedly by Mitchell, on April 29, 2010, for $28,800 and $38,400, respectively. Those two prices match works sold at Shannon's Fine Art Auctioneers, according to artnet's price database. Spoutz allegedly began to use the aliases after a fraud accusation in 2005, creating fake receipts, bills of sale and correspondence in order to provide a paper trail for the phony works, which he supposedly inherited or bought himself.