Report 1998, P

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Aboriginal & Torres Strait Islander Commission

Submission to the House of Representatives Standing Committee into The Needs of Urban* Dwelling Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Peoples By the Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Commission October 2000 * Population centres of more than 1000 people and includes peoples living in or near country towns of this size. Contents Executive Summary 3 Involvement in Decision Making 11 Maintenance of Cultural and Intellectual Property Rights 20 Education, Training, Employment & Opportunities for 26 Economic Independence Indigenous Health Needs 40 Aboriginal & Torres Strait Islander Youth 52 Mainland Torres Strait Islander Issues 69 The Role of Other Agencies & Spheres of Government 75 ATSIC Programs & Services 110 Statistical Overview 189 Acronyms & Abbreviations 204 References & Bibliography 207 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY The role of the Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Commission The Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Commission was established in 1990 to be the main Commonwealth agency in Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander affairs. Our Act gives us a variety of functions including the responsibility to: • develop policy proposals to meet national, State, Territory and regional needs and priorities, • advise the Minister on legislation, and coordination of activities of other Commonwealth bodies, • protect Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander cultural material and information, and • formulate and implement programs. In exercising these responsibilities ATSIC has given Aboriginal peoples and Torres Strait Islanders a stronger political voice. On the one hand, the most prominent Indigenous agency, ATSIC is often blamed for the fact that our people remain gravely disadvantaged. On the other hand it is not widely understood that ATSIC’s budget is meant to supplement the funding provided by the Government to other Commonwealth, State, Territory and Local Government agencies. -

Inquiry Into Government Advertising and Accountability with Amendments to Term of Reference (A)

The Senate Finance and Public Administration References Committee Government advertising and accountability December 2005 © Commonwealth of Australia 2005 ISBN 0 642 71593 9 This document is prepared by the Senate Finance and Public Administration References Committee and printed by the Senate Printing Unit, Parliament House, Canberra. Members of the Committee Senator Michael Forshaw (Chair) ALP, NSW Senator John Watson (Deputy Chair) LP, TAS Senator Carol Brown ALP, TAS Senator Mitch Fifield LP, NSW Senator Claire Moore ALP, QLD Senator Andrew Murray AD, WA Substitute member for this inquiry Senator Kim Carr ALP, VIC (replaced Senator Claire Moore from 22 June 2005) Former substitute member for this inquiry Senator Andrew Murray AD, WA (replaced Senator Aden Ridgeway 30 November 2004 to 30 June 2005) Former members Senator George Campbell (discharged 1 July 2005) Senator the Hon William Heffernan (discharged 1 July 2005) Senator Aden Ridgeway (until 30 June 2005) Senator Ursula Stephens (1 July to 13 September 2005) Participating members Senators Abetz, Bartlett, Bishop, Boswell, Brandis, Bob Brown, Carr, Chapman, Colbeck, Conroy, Coonan, Crossin, Eggleston, Evans, Faulkner, Ferguson, Ferris, Fielding, Fierravanti-Wells, Joyce, Ludwig, Lundy, Sandy Macdonald, Mason, McGauran, McLucas, Milne, Moore, O'Brien, Parry, Payne, Ray, Sherry, Siewert, Stephens, Trood and Webber. Secretariat Alistair Sands Committee Secretary Sarah Bachelard Principal Research Officer Matt Keele Research Officer Alex Hodgson Executive Assistant Committee address Senate Finance and Public Administration Committee SG.60 Parliament House CANBERRA ACT 2600 Tel: 02 6277 3530 Fax: 02 6277 5809 Email: [email protected] Internet: http://www.aph.gov.au/senate_fpa iii iv Terms of Reference On 18 November 2004, the Senate referred the following matter to the Finance and Public Administration References Committee for inquiry and report by 22 June 2005. -

Sir Walter Murdoch Memorial Lecture (1999)

Sir Walter Murdoch Memorial Lecture (1999) Millennium Dreaming: Indigenous Peoples in Australia in the era of Reconciliation Lecture delivered by: Senator Aden Ridgeway, 17 November 1999 This is the University’s premier Lecture, inaugurated in 1974, to mark the centenary of the birth of Sir Walter Murdoch, after whom the University was named. Sir Walter was the foundation Professor of English at the University of Western Australia from 1913 to 1939, and a prolific journalist whose newspaper columns were known for their shrewdness, for their clarity of thought and writing, and their propensity to deflate pomposity and humbug. He was a man who eschewed cant, a man of immense principle, and I think he would have been proud of tonight’s speaker. In the past few months, Senator Aden Ridgeway’s name has become one of the best–known in the nation. It has been said to me that he had burst onto the national political scene like a comet. But he won’t be ephemeral like a comet. There is too much substance, too much determination and commitment for him to fade away. It is given to very few Parliamentarians to play a pivotal role in a matter as weighty as reconciliation within weeks of being entering the Parliament, and to even fewer to achieve this from the upper house as a member of a minority party. But the style and strength of purpose which Senator Ridgeway displayed in persuading the Prime Minister to a point which few thought could be reached, speaks clearly for his ability and bodes well for his longevity in politics. -

Truth Telling Symposium Report

TRUTH TELLING SYMPOSIUM REPORT 5-6 OCTOBER 2018 After a shared understanding of our history, Australia looks more harmonious. It looks more cohesive. There is more love between people. There is less hatred and racism. It looks safe for our young people. It looks encouraging for our young people and the future looks bright. Karlie Stewart, The Healing Foundation Youth Advisory Group Contents Acknowledgements 3 Executive Summary 4 Background 6 Symposium launch dinner: Recognising place and restorying 8 Opening the Truth Telling Symposium 11 Session 1: The truth of the matter 12 The importance of truth telling at a national level 12 Truth telling, social justice, and reconciliation 13 Canadian Truth and Reconciliation Commission 14 Royal Commission into Institutional Responses to Child Sexual Abuse 16 Facilitated discussion: Why is truth telling important? 18 Understanding our complete national narrative 18 Not repeating the wrongs of the past 18 Restorying, being heard, healing, and changing 18 Taking ownership 19 Facilitated discussion: What truths need to be told? 19 Session 2: Reclaiming, remembering, and knowing 20 Reclaiming – repatriation 20 Remembering – looking to local leadership and advocacy on truth telling 21 Facilitated discussion: What are the important truth telling activities? 21 Session 3: Truth telling and healing 22 Facilitated discussion: What principles should guide truth telling in Australia? 23 Closing statement 24 Appendix A – Symposium Launch and Dinner program 25 Appendix B – Truth Telling Symposium program 27 Appendix C – Truth Telling Symposium Launch and Dinner attendees and Truth Telling Symposium participants 31 2 Acknowledgements The Healing Foundation and Reconciliation Australia acknowledge and pay respect to the past, present and future Traditional Custodians and Elders of this nation and the continuation of cultural, spiritual and educational practices of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples. -

Dedicated Indigenous Representation in the Australian Parliament

Parliament of Australia Department of Parliamentary Services Parliamentary Library Information, analysis and advice for the Parliament RESEARCH PAPER www.aph.gov.au/library 18 March 2009, no. 23, 2008–09, ISSN 1834-9854 Dedicated Indigenous representation in the Australian Parliament Brian Lloyd Politics and Public Administration Section Executive summary There are comparatively high levels of Indigenous representation in Australian state and territory parliaments, but none in the current federal parliament. The proposed National Indigenous Representative Body is unlikely to change this situation. A possible response is to consider dedicated Indigenous representation in Parliament. This has been a feature of the New Zealand parliament for close to 150 years, but in Australia it has remained a matter for discussion. This paper: • describes current levels of Indigenous parliamentary representation in Australia • compares levels of parliamentary representation for Indigenous people in Australia with those of Maori representation in New Zealand • details arrangements that have increased levels of Maori representation in New Zealand, including dedicated seats • canvasses arguments for and against dedicated seats • identifies obstacles to the creation of dedicated seats in Australia, and • considers future possibilities for Indigenous parliamentary representation in Australia. Proposals for dedicated seats in Australia are subject to both compelling arguments and considerable obstacles. The experience in New Zealand shows that dedicated seats do more than equalise the ‗amount‘ of parliamentary representation. Rather, they are a concrete expression of a formal relationship between Indigenous and non-Indigenous constituencies. In Australia, where such a relationship is yet to be defined, dedicated seats could play a key role in the development of such a relationship. -

Sensepublishers Multiauthor Stylefile

Fair Go Mate and Un-Australian: Australian Socio-Political Vernacular Author Kerwin, Dale Published 2010 Book Title The Havoc of Capitalism: Publics, Pedagogies and Environmental Crisis Downloaded from http://hdl.handle.net/10072/34981 Link to published version https://www.sensepublishers.com/catalogs/bookseries/bold-visions-in-educational-research/the- havoc-of-capitalism/ Griffith Research Online https://research-repository.griffith.edu.au DALE KERWIN FAIR GO MATE AND UNAUSTRALIAN: AUSTRALIAN SOCIO-POLITICAL VENACULAR In the age of the neo-conservative politics of John Howard’s Federal coalition government the individual and family became responsible for welfare rather than the government. John Howard’s Federal coalition government took a hard line ap- proach to spending on welfare priorities and this marked an ideological shift from previous federal governments’ universal policy of providing a safety net for all. Through an economical rationalist vein John Howard imposed unrealistic measures on the whole of the Australian society. This shift took away individual rights and it can be argued that the change to welfare provision impacted on Australian Abo- riginal peoples autonomy. This paper will, exam the discourses of welfare and what it means to Australian Aboriginal people within the rhetoric of self determi- nation, equality, human rights and equal justice in Australian law. As John Howard the Australian prime minister stated in 2006 “you get nothing for nothing.” At the present time in Australia and a year before a Federal election of 2007 each State and Territory in Australia is governed by the Labor Party, and the Lib- eral led coalition of the John Howard Government governs the Commonwealth of Australia. -

Date of Introduction

RBR 13/01 THE ALLOCATION OF PARLIAMENTARY SEATS FOR INDIGENOUS MINORITY GROUPS The issue of the allocation of designated parliamentary seats for indigenous groups is one that is being increasingly canvassed at a time when reconciliation has risen to national prominence. Support amongst Aboriginal leaders is high but not universal and the current Federal government has indicated that it does not support the concept. This paper explores the current position in Australia and overseas. Brian Stevenson and Wayne Jarred Research Brief 13/01 June 2001 © Queensland Parliamentary Library, 2001 ISSN 1443-7902 ISBN 0 7242 7918 0 Copyright protects this publication. Except for purposes permitted by the Copyright Act 1968, reproduction by whatever means is prohibited, other than by Members of the Queensland Parliament in the course of their official duties, without the prior written permission of the Parliamentary Librarian, Queensland Parliamentary Library. Inquiries should be addressed to: Director, Research Publications & Resources Queensland Parliamentary Library Parliament House George Street, Brisbane QLD 4000 Director: Ms Mary Seefried. (Tel: 07 3406 7116) Information about Research Publications can be found on the Internet at: Http://www.parliament.qld.gov.au/parlib/research/index.htm CONTENTS 1 INTRODUCTION ............................................................................................ 1 2 ABORIGINALS AND TORRES STRAIT ISLANDERS AS THE INDIGENOUS MINORITY GROUPS IN AUSTRALIA ............................ 1 3 THE ISSUE OF REPRESENTATION -

Indigenous Participation in Parliament

Indigenous participation in parliament 1. There have only been two Indigenous Senators in 109 years of Federal Parliament and one Indigenous politician in the House of Representatives. Neville Bonner was the first Aboriginal person to sit in Federal Parliament as a Senator for Queensland from 1971 until 1983. Neville Bonner was born on Ukerbagh Island in the Tweed River in New South Wales. He was a member of the Liberal Party. Aden Ridgeway was the second Aboriginal person to sit in Federal Parliament as a Senator for New South Wales from 1999 until 2005 and was a member of the Australian Democrats. On 24 August 2010, Kenneth George Wyatt became the first Indigenous member of the House of Representatives when he narrowly won the West Australian seat of Hasluck for the Liberal Party. Wyatt had held a position in indigenous health and education agencies for many years before his election. In his maiden speech, Wyatt received a standing ovation. During his speech, he said ‘It is with deep and mixed emotion that I, as an Aboriginal man with Noongar, Yamitji and Wongi heritage, stand before you and the members of the House of Representatives as an equal’.1 Outside of Federal Parliament, there have been a number of Indigenous representatives at a state and local government level, such as Neville Perkins, Linda Burney, Marion Scrymgour and Ben Wyatt—to name a few. 2. Nova Peris has become the first Indigenous woman to be elected to the Federal Parliament. Nova Peris OAM is Labor’s candidate for the Senate in the Northern Territory. -

Papers of Aden Ridgeway MS 4375

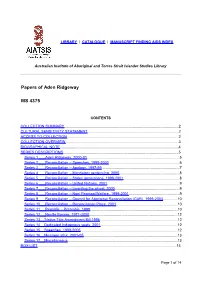

LIBRARY | CATALOGUE | MANUSCRIPT FINDING AIDS INDEX Australian Institute of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Studies Library Papers of Aden Ridgeway MS 4375 CONTENTS COLLECTION SUMMARY.............................................................................................................2 CULTURAL SENSITIVITY STATEMENT.......................................................................................2 ACCESS TO COLLECTION...........................................................................................................2 COLLECTION OVERVIEW............................................................................................................3 BIOGRAPHICAL NOTE..................................................................................................................4 SERIES DESCRIPTIONS..............................................................................................................5 Series 1 Aden Ridgeway, 2000-01 .........................................................................................5 Series 2 Reconciliation – Speeches, 1999-2002 ....................................................................6 Series 3 Reconciliation – Apology, 1997-99 ..........................................................................7 Series 4 Reconciliation – Mandatory sentencing, 2000 .........................................................8 Series 5 Reconciliation – Stolen generations, 1999-2001 ......................................................8 Series 6 Reconciliation – United Nations, -

Over Palm Island Custody Death Pat Mullins

4 July 2008 Volume: 18 Issue: 13 Restocking the global pantry James Ingram ...........................................1 ‘Still angry’ over Palm Island custody death Pat Mullins .............................................3 Egyptian musicians’ night in limbo Tim Kroenert ............................................5 Catholic teaching affirms freedom that may annoy pilgrims Frank Brennan ...........................................7 Her words’ worth Morag Fraser ............................................9 Paid leave fans the maternal flame Jen Vuk .............................................. 11 Saddam’s neck Various ............................................... 14 Guilt edged leaders Gillian Bouras .......................................... 22 Zimbabwe needs the ballot, not the bullet Oskar Wermter ......................................... 24 The place of plastic Michael Mullins ......................................... 26 Democrats’ bastard demise Tony Smith ............................................ 28 Aboriginal voices resist colonial history Kevin Brophy .......................................... 31 The truth about coal climate ‘solutions’ Tony Kevin ............................................ 33 Life becomes her Tony Kevin ............................................ 35 Incivility trumps the empty dance of manners Brian Doyle ............................................ 37 In bed with the secular spirit James McEvoy .......................................... 39 Them blackfellas Chenoah Ellis ......................................... -

ANNUAL YARRAMUNDI LECTURE 21 YEARS Anniversary Commemoration

ANNUAL YARRAMUNDI LECTURE 21 YEARS Anniversary Commemoration ANNUAL YARRAMUNDI LECTURE – 21 YEARS ANNIVERSARY COMMEMORATION PAGE 1 MELISSA WILLIAMS PRINCIPAL RESEARCHER THE HEART OF THE MATTER The annual Yarramundi Lectures have a simple premise with a profound outcome. They provide a high profile means for Elders, leaders of the many Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander communities throughout Australia, to express and debate meaningful concerns that affect Front Cover Image: iMedia their communities. © 2017 Elders on Campus, Office of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Employment and Engagement, Western Sydney University By being heard and understood, they are brought closer together in heart and This work is copyright. Apart from any use as permitted under the Copyright mind with their fellow Aboriginal and Act 1968, no part may be reproduced by any process without written Torres Strait Islander Peoples and all other permission from the Elders on Campus, Office of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Employment and Engagement, Western Sydney University. Requests Australians. All our clans, our communities and enquiries concerning reproduction should be addressed to: and our different cultures are able to walk together. In this way, we are all given the opportunity to invest in each Elders on Campus other. We are all included in the making of a better, collective Australia. Office of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Employment and Engagement Western Sydney University Locked Bag 1797, Penrith NSW 2751 The Yarramundi Lectures are the lightning rod that attracts the positive energy and power we all have stored up within ourselves. It is this energy This publication is available online at westernsydney.edu.au/oatsiee that has the power to heal, to grow and to celebrate all that is good Every reasonable effort has been made to contact copyright owners of materials within us and about us. -

Work of Committees

PART ONE 1 July 2004 - 15 November 2004 (end of the 40th Parliament) Legislative and General Purpose Standing Committees administered by the Senate Committee Office Community Affairs Community Affairs 1 July - 15 November Matters referred Reports Matters current as during period tabled that Current inquiries as at 1 July (including estimates discharge a at 15 November and annual reports) reference Legislation 1 0 1 0 References 3 0 0 +(2*) 3 Total 4 0 1 3 *Reports that did not discharge a reference Number and Hours of Meeting Total Public Hrs Public Estimates Hrs Private Hrs Insp/Other Hrs Meetings Total Hours Legislation 1 1:05 0 0:00 0 0:00 0 0:00 1 1:05 References 1 7:20 0 0:00 3 3:30 0 0:00 4 10:50 Total 2 8:25 0 0:00 3 3:30 0 0:00 5 11:55 6 Meetings By State ACT NSW VIC TAS SA WA NT QLD Legislation 1 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 References 3 1 0 0 0 0 0 0 Total 4 1 0 0 0 0 0 0 Witnesses Hansard Pages Televised No of Government No Of Pages Hearings Estimates Other (Bills) General Estimates Other (Bills) General Submissions Responses Legislation 10 05 0 019140 References 0 0 0 18 0 0 109 134 1078 0 Total 1 0 0 23 0 0 128 135 1082 0 Community Affairs Legislation 40th Parliament (1 July 2004 to 15 November 2004) Method of appointment Pursuant to Senate Standing Order 25. Current members Date of appointment Senator Susan Knowles (WA, LP) (elected Chair-20.12.03) 20.12.03 Senator Brian Greig (WA, AD) (elected Deputy Chair 12.2.03) 18.11.02 Senator Guy Barnett (Tas, LP) 3.12.03 Senator Kay Denman (Tas, ALP) 13.2.02 Senator Gary Humphries (ACT, LP) (Chair-22.8.03