A Critical Analysis of Cosmic Symbolism in Musical

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

4 All the UK Case Studies and People Like You

For people like us 4 All the UK Case studies and people like you 3 Contents 4 Introduction Alex Mahon, Chief Executive, Channel 4 6 Viewpoint One year on Sinéad Rocks, Managing Director, Nations and Regions, Channel 4 8 Leeds 10 Viewpoint Roger Marsh OBE, Chair, Leeds City Region Enterprise Partnership and NP11 12 Case study: Steph’s Packed Lunch 14 Bristol 16 Glasgow 18 Manchester 4 All the UK case studies 20 Harjeet Chhokar 21 Kate Thomas 22 Barry Agnew 23 Sharon Chapendama 4 All the UK 24 Emerging Indie Fund and Indie Growth Fund 26 4Studio 28 4Skills 30 Viewpoint Sally Joynson, CEO, Screen Yorkshire 32 Contacts 4 Introduction When we set out our 4 All the UK We’ve also committed to upping strategy just over two years ago, our spend on creative content in the it sparked the largest structural Nations and Regions – from 35% to shake-up in Channel 4’s history. 50% of main channel UK commissions by 2023, worth up to £250 million We knew that if we were going to more in total. Plus, we’ve announced truly fulfil our remit to stand up for a new Emerging Indie Fund to help diversity, take creative risks and budding early stage production inspire change, we’d need to change companies from across the country to too. We’d need to look and feel break into new genres and scale up. different, behave differently and most importantly, get outside the M25. Through our new 4Skills training and development initiative, we’re making After a bidding process that involved sure that Channel 4 is even more open to most major cities in the country, we new talent and fresh voices from picked Leeds as our new national HQ. -

Political Performance and the War on Terror

The Shock and Awe of the Real: Political Performance and the War on Terror by Matthew Jones A thesis submitted in conformity with the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Centre for Drama, Theatre and Performance Studies University of Toronto © Copyright by Matt Jones 2020 The Shock and Awe of the Real: Political Performance and the War on Terror Matt Jones Doctor of Philosophy Centre for Drama, Theatre and Performance Studies University of Toronto 2020 Abstract This dissertation offers a transnational study of theatre and performance that responded to the recent conflicts in Iraq, Afghanistan, Syria, and beyond. Looking at work by artists primarily from Arab and Middle Eastern diasporas working in the US, UK, Canada, and Europe, the study examines how modes of performance in live art, documentary theatre, and participatory performance respond to and comment on the power imbalances, racial formations, and political injustices of these conflicts. Many of these performances are characterized by a deliberate blurring of the distinctions between performance and reality. This has meant that playwrights crafted scripts from the real words of soldiers instead of writing plays; performance artists harmed their real bodies, replicating the violence of war; actors performed in public space; and media artists used new technology to connect audiences to real warzones. This embrace of the real contrasts with postmodern suspicion of hyper-reality—which characterized much political performance in the 1990s—and marks a shift in understandings of the relationship between performance and the real. These strategies allowed artists to contend with the way that war today is also a multimedia attack on the way that reality is constructed and perceived. -

Night of 100 Solos: a Centennial Event

2019 Winter/Spring Season Brooklyn Academy of Music Adam E. Max, Katy Clark, BAM Board Chair President William I. Campbell and Nora Ann Wallace David Binder, BAM Board Vice Chairs Artistic Director Night of 100 Solos: A Centennial Event Choreography by Merce Cunningham BAM Howard Gilman Opera House Apr 16 at 7:30pm Running time: approx. 90 minutes, no intermission Presented without inter- Stager Patricia Lent mission, Events consist of Associate stager Jean Freebury excerpts of dances from the Music director John King repertory and new sequences Set designer Pat Steir arranged for the particular performance and place, Costume designers and builders Reid Bartelme & Harriet Jung with the possibility of several Lighting designer Christine Schallenberg separate activities happening Technical director Davison Scandrett at the same time. —Merce Cunningham Co-produced by Brooklyn Academy of Music, the Barbican London, UCLA’s Center for the Art of Performance, and the Merce Cunningham Trust Night of 100 Solos: A Centennial Event is part of the Merce Cunningham Centennial. Night of 100 Solos: A Centennial Event is generously supported by a major grant from the Howard Gilman Foundation. 2019 Winter/Spring is programmed by Joseph V. Melillo. Season Sponsor: Leadership support for dance at BAM provided by The Harkness Foundation for Dance Major support for dance at BAM provided by The SHS Foundation Support for the Signature Artists Series provided by the Howard Gilman Foundation Night of 100 Solos DANCERS Kyle Abraham, Christian Allen, Mariah Anton -

MSW Student Handbook

MSW Student Handbook College of Adult and Professional Studies School of Service and Leadership Department of Behavioral Sciences Master of Social Work Program 4201 S. Washington St. Marion, IN 46953 Phone 765.677.2363 Fax 765.677.1827 2021 Social Work Education Indiana Wesleyan University David King, DSW, MA, MSW, LMSW Program Director, Associate Professor, MSW Program [email protected] 734-657-8717 Cynthia Faulkner, Ph.D., MSW, LCSW Professor, MSW Program [email protected] (606) 356-7094 Brian Roland, Ph.D., MSW, LMSW Assistant Professor, MSW Program [email protected] 518-888-4121 Toby Buchanan, Ph.D., LMSW Professor, MSW Program [email protected] Marcie Cutsinger, Ed.D., MSW, LCSW Assistant Professor, MSW Program [email protected] 660.359.1856 James Long, Jr., Th.D., MSW, LCSW Associate Professor, Field Director, MSW Program [email protected] 201.341.5119 Katti Sneed Ph.D., MSW, LCSW Professor, Marion Hybrid Cohort, Director [email protected] 765-506-1391 Theresa Veach, Ph.D., HSPP Chair, Department of Behavioral Sciences School of Service and Leadership [email protected] 800.621.8667 / 756.677.2348 Kristy White Behavioral Sciences Administrative Assistant [email protected] 800.677.8667 / 765.677.2363 Social Work Advising MSW Program [email protected] 800-621-8667, ex 3323 / 765-677-332 2021 Table of Contents Message from the Director of the MSW Program .................................................................................................................. -

Courtney Harding, Is Excited to Start Her Second Year As a TACT Academy Instructor

Denise S Bass, has several television credits to her name including Matlock, One Tree Hill, HBO's East Bound and Down with Danny McBride and Katy Mixon, and TNT's production of T-Bone and Weasel starring Gregory Hines, Christopher Lloyd, and Wayne Knight. Also to her credit are several film productions including The Road to Wellville with Anthony Hopkins and Matthew Broderick, Black Knight with Martin Laurence, and The 27 Club with Joe Anderson. She has been performing theatrically since 1981 working from NC to Florida and touring the Southeast with the American Family Theatre out of Philadelphia. Denise's most recent roles include Ethel in Thalian Association's production of "Barefoot in the Park" (Winner 2017 Thalian Award Best Actress in a Play), Dottie in Thalian Association's production of "Noises Off" (Nominee 2016 Thalian Award Best Supporting Actress in a Play), and Madam Thenadier in Opera House Theatre Company's production of Les Miserable. Other notable roles over the years include Sally in "Follies", Dolly Levi in "Hello, Dolly!", Molly Brown in "The Unsinkable Molly Brown", Delightful in "Dearly Departed", Diana Morales in "A Chorus Line", and Mrs. Meers in "Throughly Modern Mille”. She is a producer and featured performer with Ensemble Audio Studios and was part of the cast for the audio production of "The King's Child", which was selected in 2017 at the Hear Now Audio Festival for the Gold Circle Page. She also voiced several characters for the very popular audio book "Percy the Cat and the Big White House". She is currently writing a collection of short stories and looks forward to teaching Fundamentals of Acting for TACT. -

Razorcake Issue #82 As A

RIP THIS PAGE OUT WHO WE ARE... Razorcake exists because of you. Whether you contributed If you wish to donate through the mail, any content that was printed in this issue, placed an ad, or are a reader: without your involvement, this magazine would not exist. We are a please rip this page out and send it to: community that defi es geographical boundaries or easy answers. Much Razorcake/Gorsky Press, Inc. of what you will fi nd here is open to interpretation, and that’s how we PO Box 42129 like it. Los Angeles, CA 90042 In mainstream culture the bottom line is profi t. In DIY punk the NAME: bottom line is a personal decision. We operate in an economy of favors amongst ethical, life-long enthusiasts. And we’re fucking serious about it. Profi tless and proud. ADDRESS: Th ere’s nothing more laughable than the general public’s perception of punk. Endlessly misrepresented and misunderstood. Exploited and patronized. Let the squares worry about “fi tting in.” We know who we are. Within these pages you’ll fi nd unwavering beliefs rooted in a EMAIL: culture that values growth and exploration over tired predictability. Th ere is a rumbling dissonance reverberating within the inner DONATION walls of our collective skull. Th ank you for contributing to it. AMOUNT: Razorcake/Gorsky Press, Inc., a California not-for-profit corporation, is registered as a charitable organization with the State of California’s COMPUTER STUFF: Secretary of State, and has been granted official tax exempt status (section 501(c)(3) of the Internal Revenue Code) from the United razorcake.org/donate States IRS. -

The-Music-Of-Andrew-Lloyd-Webber Programme.Pdf

Photograph: Yash Rao We’re thrilled to welcome you safely back to Curve for production, in particular Team Curve and Associate this very special Made at Curve concert production of Director Lee Proud, who has been instrumental in The Music of Andrew Lloyd Webber. bringing this show to life. Over the course of his astonishing career, Andrew It’s a joy to welcome Curve Youth and Community has brought to life countless incredible characters Company (CYCC) members back to our stage. Young and stories with his thrilling music, bringing the joy of people are the beating heart of Curve and after such MUSIC BY theatre to millions of people across the world. In the a long time away from the building, it’s wonderful to ANDREW LLOYD WEBBER last 15 months, Andrew has been at the forefront of have them back and part of this production. Guiding conversations surrounding the importance of theatre, our young ensemble with movement direction is our fighting for the survival of our industry and we are Curve Associate Mel Knott and we’re also thrilled CYCC LYRICS BY indebted to him for his tireless advocacy and also for alumna Alyshia Dhakk joins us to perform Pie Jesu, in TIM RICE, DON BLACK, CHARLES HART, CHRISTOPHER HAMPTON, this gift of a show, celebrating musical theatre, artists memory of all those we have lost to the pandemic. GLENN SLATER, DAVID ZIPPEL, RICHARD STILGOE AND JIM STEINMAN and our brilliant, resilient city. Known for its longstanding Through reopening our theatre we are not only able to appreciation of musicals, Leicester plays a key role make live work once more and employ 100s of freelance in this production through Andrew’s pre-recorded DIRECTED BY theatre workers, but we are also able to play an active scenes, filmed on-location in and around Curve by our role in helping our city begin to recover from the impact NIKOLAI FOSTER colleagues at Crosscut Media. -

Finding Aid for the Sheldon Harris Collection (MUM00682)

University of Mississippi eGrove Archives & Special Collections: Finding Aids Library November 2020 Finding Aid for the Sheldon Harris Collection (MUM00682) Follow this and additional works at: https://egrove.olemiss.edu/finding_aids Recommended Citation Sheldon Harris Collection, Archives and Special Collections, J.D. Williams Library, The University of Mississippi This Finding Aid is brought to you for free and open access by the Library at eGrove. It has been accepted for inclusion in Archives & Special Collections: Finding Aids by an authorized administrator of eGrove. For more information, please contact [email protected]. University of Mississippi Libraries Finding aid for the Sheldon Harris Collection MUM00682 TABLE OF CONTENTS SUMMARY INFORMATION Summary Information Repository University of Mississippi Libraries Biographical Note Creator Scope and Content Note Harris, Sheldon Arrangement Title Administrative Information Sheldon Harris Collection Related Materials Date [inclusive] Controlled Access Headings circa 1834-1998 Collection Inventory Extent Series I. 78s 49.21 Linear feet Series II. Sheet Music General Physical Description note Series III. Photographs 71 boxes (49.21 linear feet) Series IV. Research Files Location: Blues Mixed materials [Boxes] 1-71 Abstract: Collection of recordings, sheet music, photographs and research materials gathered through Sheldon Harris' person collecting and research. Prefered Citation Sheldon Harris Collection, Archives and Special Collections, J.D. Williams Library, The University of Mississippi Return to Table of Contents » BIOGRAPHICAL NOTE Born in Cleveland, Ohio, Sheldon Harris was raised and educated in New York City. His interest in jazz and blues began as a record collector in the 1930s. As an after-hours interest, he attended extended jazz and blues history and appreciation classes during the late 1940s at New York University and the New School for Social Research, New York, under the direction of the late Dr. -

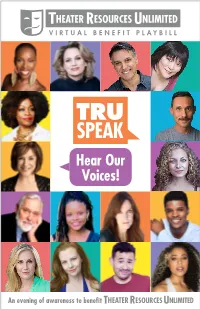

TRU Speak Program 021821 XS

THEATER RESOURCES UNLIMITED VIRTUAL BENEFIT PLAYBILL TRU SPEAK Hear Our Voices! An evening of awareness to benefit THEATER RESOURCES UNLIMITED executive producer Bob Ost associate producers Iben Cenholt and Joe Nelms benefit chair Sanford Silverberg plays produced by Jonathan Hogue, Stephanie Pope Lofgren, James Rocco, Claudia Zahn assistant to the producers Maureen Condon technical coordinator Iben Cenholt/RuneFilms editor-technologists Iben Cenholt/RuneFilms, Andrea Lynn Green, Carley Santori, Henry Garrou/Whitetree, LLC video editors Sam Berland/Play It Again Sam’s Video Productions, Joe Nelms art direction & graphics Gary Hughes casting by Jamibeth Margolis Casting Social Media Coordinator Jeslie Pineda featuring MAGGIE BAIRD • BRENDAN BRADLEY • BRENDA BRAXTON JIM BROCHU • NICK CEARLEY • ROBERT CUCCIOLI • ANDREA LYNN GREEN ANN HARADA • DICKIE HEARTS • CADY HUFFMAN • CRYSTAL KELLOGG WILL MADER • LAUREN MOLINA • JANA ROBBINS • REGINA TAYLOR CRYSTAL TIGNEY • TATIANA WECHSLER with Robert Batiste, Jianzi Colon-Soto, Gha'il Rhodes Benjamin, Adante Carter, Tyrone Hall, Shariff Sinclair, Taiya, and Stephanie Pope Lofgren as the Voice of TRU special appearances by JERRY MITCHELL • BAAYORK LEE • JAMES MORGAN • JILL PAICE TONYA PINKINS •DOMINIQUE SHARPTON • RON SIMONS HALEY SWINDAL • CHERYL WIESENFELD TRUSpeak VIP After Party hosted by Write Act Repertory TRUSpeak VIP After Party production and tech John Lant, Tamra Pica, Iben Cenholt, Jennifer Stewart, Emily Pierce Virtual Happy Hour an online musical by Richard Castle & Matthew Levine directed -

National Press Club Luncheon with Douglas Wilder, Mayor of Richmond, Virginia and Former Governor of Virginia, Accompanied by Ben Vereen, Actor

NATIONAL PRESS CLUB LUNCHEON WITH DOUGLAS WILDER, MAYOR OF RICHMOND, VIRGINIA AND FORMER GOVERNOR OF VIRGINIA, ACCOMPANIED BY BEN VEREEN, ACTOR SUBJECT: "CONFRONTING THE ISSUE OF SLAVERY: THE UNEXPLORED CHAPTER IN AMERICAN HISTORY" MODERATOR: JONATHAN SALANT, PRESIDENT, NPC AND REPORTER, BLOOMBERG NEWS LOCATION: NATIONAL PRESS CLUB BALLROOM, WASHINGTON, D.C. TIME: 1:00 P.M. EST DATE: TUESDAY, FEBRUARY 7, 2006 (C) COPYRIGHT 2005, FEDERAL NEWS SERVICE, INC., 1000 VERMONT AVE. NW; 5TH FLOOR; WASHINGTON, DC - 20005, USA. ALL RIGHTS RESERVED. ANY REPRODUCTION, REDISTRIBUTION OR RETRANSMISSION IS EXPRESSLY PROHIBITED. UNAUTHORIZED REPRODUCTION, REDISTRIBUTION OR RETRANSMISSION CONSTITUTES A MISAPPROPRIATION UNDER APPLICABLE UNFAIR COMPETITION LAW, AND FEDERAL NEWS SERVICE, INC. RESERVES THE RIGHT TO PURSUE ALL REMEDIES AVAILABLE TO IT IN RESPECT TO SUCH MISAPPROPRIATION. FEDERAL NEWS SERVICE, INC. IS A PRIVATE FIRM AND IS NOT AFFILIATED WITH THE FEDERAL GOVERNMENT. NO COPYRIGHT IS CLAIMED AS TO ANY PART OF THE ORIGINAL WORK PREPARED BY A UNITED STATES GOVERNMENT OFFICER OR EMPLOYEE AS PART OF THAT PERSON'S OFFICIAL DUTIES. FOR INFORMATION ON SUBSCRIBING TO FNS, PLEASE CALL JACK GRAEME AT 202-347-1400. ------------------------- MR. SALANT: (Sounds gavel.) Good afternoon and welcome to the National Press Club. I'm Jonathan Salant, a reporter for Bloomberg News and president of the National Press Club. I'd like to welcome club members and their guests in the audience today, as well as those of you watching on C-SPAN. Please hold your applause during the speech so we have time for as many questions as possible. For our broadcast audience, I'd like to explain that if you hear applause, it is from the members of the general public and the guests who attend our luncheons, not from the working press. -

Label ARTIST Piece Tracks/Notes Format Quantity

Label ARTIST Piece Tracks/notes Format Quantity Sire Against Me! 2 song 7" single I Was A Teenage Anarchist (acoustic) 7" vinyl 2500 Sub-pop Album Leaf There Is a Wind Featuring 2 new tracks, 2 alternate takes 12" vinyl 1000 on songs from "A Chorus of Storytellers" LP Righteous Babe Ani DiFranco live @ Bull Moose recorded live on Record Store Day at CD Bull Moose in Maine Rough Trade Arthur Russell Calling Out of Context 12 new tracks Double 12" set 2000 Rocket Science Asteroids Galaxy Tour Fun Ltd edition vinyl of album with bonus 12" 250 track "Attack of the Ghost Riders" Hopeless Avenged Sevenfold Unholy Confessions picture disc includes tracks (Eternal 12" vinyl 2000 Rest, Eternal Rest (live), Unholy Confessions Artist First/Shangri- Band of Skulls Live at Fingerprints Live EP recorded at record store CD 2000 la 12/15/2009 Fingerprints Sub-pop Beach House Zebra 2 new tracks and 2 alternate from album 12" vinyl 1500 "Teen Dream" Beastie Boys white label 12" super surprise 12" vinyl 1000 Nonesuch Black Keys Tighten Up/Howlin' For 12" vinyl contains two new songs 45 RPM 12" Single 50000 You Vinyl Eagle Rock Black Label Society Skullage Double LP look at the history of Zakk Double LP 180 Wylde and Black Label Society Gram GREEN vinyl Graveface Black Moth Super Eating Us extremely limited foil pressed double LP double LP Rainbow Jagjaguwar Bon Iver/Peter Gabriel "Come Talk To Bon Iver and Peter Gabriel cover each 7" vinyl 2000 Me"/"Flume" other. Bon Iver track is EXCLUSIVE to this release Ninja Tune Bonobo featuring "Eyes -

“Whiskey in the Jar”: History and Transformation of a Classic Irish Song Masters Thesis Presented in Partial Fulfillment Of

“Whiskey in the Jar”: History and Transformation of a Classic Irish Song Masters Thesis Presented in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By Dana DeVlieger, B.A., M.A. Graduate Program in Music The Ohio State University 2016 Thesis Committee: Graeme M. Boone, Advisor Johanna Devaney Anna Gawboy Copyright by Dana Lauren DeVlieger 2016 Abstract “Whiskey in the Jar” is a traditional Irish song that is performed by musicians from many different musical genres. However, because there are influential recordings of the song performed in different styles, from folk to punk to metal, one begins to wonder what the role of the song’s Irish heritage is and whether or not it retains a sense of Irish identity in different iterations. The current project examines a corpus of 398 recordings of “Whiskey in the Jar” by artists from all over the world. By analyzing acoustic markers of Irishness, for example an Irish accent, as well as markers of other musical traditions, this study aims explores the different ways that the song has been performed and discusses the possible presence of an “Irish feel” on recordings that do not sound overtly Irish. ii Dedication Dedicated to my grandfather, Edward Blake, for instilling in our family a love of Irish music and a pride in our heritage iii Acknowledgments I would like to thank my advisor, Graeme Boone, for showing great and enthusiasm for this project and for offering advice and support throughout the process. I would also like to thank Johanna Devaney and Anna Gawboy for their valuable insight and ideas for future directions and ways to improve.