Chameleons of Modern Drumming: Mastering Diverse Commerical Styles

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Excesss Karaoke Master by Artist

XS Master by ARTIST Artist Song Title Artist Song Title (hed) Planet Earth Bartender TOOTIMETOOTIMETOOTIM ? & The Mysterians 96 Tears E 10 Years Beautiful UGH! Wasteland 1999 Man United Squad Lift It High (All About 10,000 Maniacs Candy Everybody Wants Belief) More Than This 2 Chainz Bigger Than You (feat. Drake & Quavo) [clean] Trouble Me I'm Different 100 Proof Aged In Soul Somebody's Been Sleeping I'm Different (explicit) 10cc Donna 2 Chainz & Chris Brown Countdown Dreadlock Holiday 2 Chainz & Kendrick Fuckin' Problems I'm Mandy Fly Me Lamar I'm Not In Love 2 Chainz & Pharrell Feds Watching (explicit) Rubber Bullets 2 Chainz feat Drake No Lie (explicit) Things We Do For Love, 2 Chainz feat Kanye West Birthday Song (explicit) The 2 Evisa Oh La La La Wall Street Shuffle 2 Live Crew Do Wah Diddy Diddy 112 Dance With Me Me So Horny It's Over Now We Want Some Pussy Peaches & Cream 2 Pac California Love U Already Know Changes 112 feat Mase Puff Daddy Only You & Notorious B.I.G. Dear Mama 12 Gauge Dunkie Butt I Get Around 12 Stones We Are One Thugz Mansion 1910 Fruitgum Co. Simon Says Until The End Of Time 1975, The Chocolate 2 Pistols & Ray J You Know Me City, The 2 Pistols & T-Pain & Tay She Got It Dizm Girls (clean) 2 Unlimited No Limits If You're Too Shy (Let Me Know) 20 Fingers Short Dick Man If You're Too Shy (Let Me 21 Savage & Offset &Metro Ghostface Killers Know) Boomin & Travis Scott It's Not Living (If It's Not 21st Century Girls 21st Century Girls With You 2am Club Too Fucked Up To Call It's Not Living (If It's Not 2AM Club Not -

Title MPOP Collection Vol.3, 400 Songs NR

NR. NO ARTIST A PICTURE OF ME (WITHOUT YOU) 50995 GEORGE JONES A WOMAN ALWAYS KNOWS 52017 DAVID HOUSTON AFRICA 08044 TOTO AFTER MIDNIGHT 06810 ERIC CLAPTON AFTER THE LOVIN' 06802 ENGELBERT HUMPERDINCK AIN'T THAT LONELY YET 50474 DWIGHT YOAKAM ALL FOR LOVE 06148 B.ADAMS / R.STEWART / STING ALL FOR YOU 07049 JANET JACKSON ALL I WANT 50161 TOAD THE WET SPROCKET ALL MY LIFE 52037 AMERICA ALL MY LOVING 06196 BEATLES ALL OUT OF LOVE 06042 AIR SUPPLY ALMOST PARADISE 06006 MIKE RENO & ANN WILSON ALWAYS 06328 BON JOVI AMANDA 52018 WAYLON JENNINGS AMAZED 50475 LONESTAR AMAZING GRACE 07152 JUDY COLLINS AND I LOVE HER 06198 BEATLES ANDANTE, ANDANTE 08141 ABBA ANNIE'S SONG 07112 JOHN DENVER ANYTHING IS POSSIBLE 50218 WILL YOUNG ANYTIME 50191 THE JETS ANYWHERE BUT HERE 50628 HILARY DUFF APRIL COME SHE WILL 50299 SIMON & GARFUNKEL ARE YOU EXPERIENCED? 52038 JIMI HENDRIX AUTUMN LEAVES 06091 ANDY WILLIAMS BABY 51782 ASHANTI BABY I'M A WANT YOU 09424 BREAD BAD 07427 MICHAEL JACKSON www.magic-sing.be Title MPOP Collection Vol.3, 400 songs NR. NO ARTIST BAD DAY 52091 FUEL BE 07506 NEIL DIAMOND BE MY BABY 07785 RONETTES BEAUTY AND THE BEAST 06487 CELINE DION / P.BRYSON BECAUSE I LOVE YOU 51736 PHIL COLLINS BECAUSE OF YOU 06013 98 DEGREES BEDTIME STORY 07974 TAMMY WYNETTE BELIEVE 06497 CHER BETTER CLASS OF LOSERS 52032 RANDY TRAVIS BIGGER THAN MY BODY 08186 JOHN MAYER BLACK CAT 51786 JANET JACKSON BLACK OR WHITE 07431 MICHAEL JACKSON BLACK SHEEP 50338 JOHN ANDERSON BLUE 50631 EIFFEL 65 BOOGIE WONDERLAND 50409 EARTH WIND & FIRE BOOGIE WOOGIE BUGLE BOY 09605 -

PASIC 2010 Program

201 PASIC November 10–13 • Indianapolis, IN PROGRAM PAS President’s Welcome 4 Special Thanks 6 Area Map and Restaurant Guide 8 Convention Center Map 10 Exhibitors by Name 12 Exhibit Hall Map 13 Exhibitors by Category 14 Exhibitor Company Descriptions 18 Artist Sponsors 34 Wednesday, November 10 Schedule of Events 42 Thursday, November 11 Schedule of Events 44 Friday, November 12 Schedule of Events 48 Saturday, November 13 Schedule of Events 52 Artists and Clinicians Bios 56 History of the Percussive Arts Society 90 PAS 2010 Awards 94 PASIC 2010 Advertisers 96 PAS President’s Welcome elcome 2010). On Friday (November 12, 2010) at Ten Drum Art Percussion Group from Wback to 1 P.M., Richard Cooke will lead a presen- Taiwan. This short presentation cer- Indianapolis tation on the acquisition and restora- emony provides us with an opportu- and our 35th tion of “Old Granddad,” Lou Harrison’s nity to honor and appreciate the hard Percussive unique gamelan that will include a short working people in our Society. Arts Society performance of this remarkable instru- This year’s PAS Hall of Fame recipi- International ment now on display in the plaza. Then, ents, Stanley Leonard, Walter Rosen- Convention! on Saturday (November 13, 2010) at berger and Jack DeJohnette will be We can now 1 P.M., PAS Historian James Strain will inducted on Friday evening at our Hall call Indy our home as we have dig into the PAS instrument collection of Fame Celebration. How exciting to settled nicely into our museum, office and showcase several rare and special add these great musicians to our very and convention space. -

Allan Holdsworth Schille Reshaping Harmony

BJØRN ALLAN HOLDSWORTH SCHILLE RESHAPING HARMONY Master Thesis in Musicology - February 2011 Institute of Musicology| University of Oslo 3001 2 2 Acknowledgment Writing this master thesis has been an incredible rewarding process, and I would like to use this opportunity to express my deepest gratitude to those who have assisted me in my work. Most importantly I would like to thank my wonderful supervisors, Odd Skårberg and Eckhard Baur, for their good advice and guidance. Their continued encouragement and confidence in my work has been a source of strength and motivation throughout these last few years. My thanks to Steve Hunt for his transcription of the chord changes to “Pud Wud” and helpful information regarding his experience of playing with Allan Holdsworth. I also wish to thank Jeremy Poparad for generously providing me with the chord changes to “The Sixteen Men of Tain”. Furthermore I would like to thank Gaute Hellås for his incredible effort of reviewing the text and providing helpful comments where my spelling or formulations was off. His hard work was beyond what any friend could ask for. (I owe you one!) Big thanks to friends and family: Your love, support and patience through the years has always been, and will always be, a source of strength. And finally I wish to acknowledge Arne Torvik for introducing me to the music of Allan Holdsworth so many years ago in a practicing room at the Grieg Academy of Music in Bergen. Looking back, it is obvious that this was one of those life-changing moments; a moment I am sincerely grateful for. -

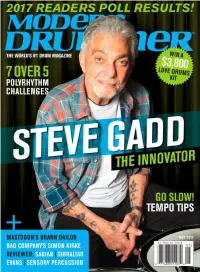

40 Steve Gadd Master: the Urgency of Now

DRIVE Machined Chain Drive + Machined Direct Drive Pedals The drive to engineer the optimal drive system. mfg Geometry, fulcrum and motion become one. Direct Drive or Chain Drive, always The Drummer’s Choice®. U.S.A. www.DWDRUMS.COM/hardware/dwmfg/ 12 ©2017Modern DRUM Drummer WORKSHOP, June INC. ALL2014 RIGHTS RESERVED. ROLAND HYBRID EXPERIENCE RT-30H TM-2 Single Trigger Trigger Module BT-1 Bar Trigger RT-30HR Dual Trigger RT-30K Learn more at: Kick Trigger www.RolandUS.com/Hybrid EXPERIENCE HYBRID DRUMMING AT THESE LOCATIONS BANANAS AT LARGE RUPP’S DRUMS WASHINGTON MUSIC CENTER SAM ASH CARLE PLACE CYMBAL FUSION 1504 4th St., San Rafael, CA 2045 S. Holly St., Denver, CO 11151 Veirs Mill Rd., Wheaton, MD 385 Old Country Rd., Carle Place, NY 5829 W. Sam Houston Pkwy. N. BENTLEY’S DRUM SHOP GUITAR CENTER HALLENDALE THE DRUM SHOP COLUMBUS PRO PERCUSSION #401, Houston, TX 4477 N. Blackstone Ave., Fresno, CA 1101 W. Hallandale Beach Blvd., 965 Forest Ave., Portland, ME 5052 N. High St., Columbus, OH MURPHY’S MUSIC GELB MUSIC Hallandale, FL ALTO MUSIC RHYTHM TRADERS 940 W. Airport Fwy., Irving, TX 722 El Camino Real, Redwood City, CA VIC’S DRUM SHOP 1676 Route 9, Wappingers Falls, NY 3904 N.E. Martin Luther King Jr. SALT CITY DRUMS GUITAR CENTER SAN DIEGO 345 N. Loomis St. Chicago, IL GUITAR CENTER UNION SQUARE Blvd., Portland, OR 5967 S. State St., Salt Lake City, UT 8825 Murray Dr., La Mesa, CA SWEETWATER 25 W. 14th St., Manhattan, NY DALE’S DRUM SHOP ADVANCE MUSIC CENTER SAM ASH HOLLYWOOD DRUM SHOP 5501 U.S. -

Downbeat.Com December 2014 U.K. £3.50

£3.50 £3.50 . U.K DECEMBER 2014 DOWNBEAT.COM D O W N B E AT 79TH ANNUAL READERS POLL WINNERS | MIGUEL ZENÓN | CHICK COREA | PAT METHENY | DIANA KRALL DECEMBER 2014 DECEMBER 2014 VOLUME 81 / NUMBER 12 President Kevin Maher Publisher Frank Alkyer Editor Bobby Reed Associate Editor Davis Inman Contributing Editor Ed Enright Art Director LoriAnne Nelson Contributing Designer Žaneta Čuntová Bookkeeper Margaret Stevens Circulation Manager Sue Mahal Circulation Associate Kevin R. Maher Circulation Assistant Evelyn Oakes ADVERTISING SALES Record Companies & Schools Jennifer Ruban-Gentile 630-941-2030 [email protected] Musical Instruments & East Coast Schools Ritche Deraney 201-445-6260 [email protected] Advertising Sales Associate Pete Fenech 630-941-2030 [email protected] OFFICES 102 N. Haven Road, Elmhurst, IL 60126–2970 630-941-2030 / Fax: 630-941-3210 http://downbeat.com [email protected] CUSTOMER SERVICE 877-904-5299 / [email protected] CONTRIBUTORS Senior Contributors: Michael Bourne, Aaron Cohen, Howard Mandel, John McDonough Atlanta: Jon Ross; Austin: Kevin Whitehead; Boston: Fred Bouchard, Frank- John Hadley; Chicago: John Corbett, Alain Drouot, Michael Jackson, Peter Margasak, Bill Meyer, Mitch Myers, Paul Natkin, Howard Reich; Denver: Norman Provizer; Indiana: Mark Sheldon; Iowa: Will Smith; Los Angeles: Earl Gibson, Todd Jenkins, Kirk Silsbee, Chris Walker, Joe Woodard; Michigan: John Ephland; Minneapolis: Robin James; Nashville: Bob Doerschuk; New Orleans: Erika Goldring, David Kunian, Jennifer Odell; New York: Alan Bergman, -

John Anthony Final Revisions Thesis

Improvisational Devices of Jazz Guitarist Adam Rogers on the Thelonious Monk Composition “Let’s Cool One” by John J. Anthony Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Music in Jazz Studies YOUNGSTOWN STATE UNIVERSITY August, 2012 Improvisational Devices of Jazz Guitarist Adam Rogers on the Thelonious Monk Composition “Let’s Cool One” John J. Anthony I hereby release this thesis to the public. I understand that this thesis will be made available from the OhioLINK ETD Center and the Maag Library Circulation Desk for public access. I also authorize the University or other individuals to make copies of this thesis as needed for scholarly research. Signature: John J. Anthony, Student Date Approvals: Dr. David Morgan, Thesis Advisor Date Dr. Kent Engelhardt, Committee Member Date Dr. Randall Goldberg, Committee Member Date Dr. Glenn Schaft, Committee Member Date Peter J. Kasvinsky, Dean of School of Graduate Studies and Research Date ABSTRACT Adam Rogers is one of the most influential jazz guitarists in the world today. This thesis offers a transcription and analysis of his improvisation on the Thelonious Monk composition “Let’s Cool One” which demonstrates five improvisational devices that define Rogers’s approach over this composition: micro-harmonization, rhythmic displacement, motivic development, thematic improvisation, and phrase rhythm. This thesis presents a window into the aesthetics of contemporary jazz improvisation and offers a prism for conceptualizing not only the work of Adam Rogers, but -

Various Funky Beats Mp3, Flac, Wma

Various Funky Beats mp3, flac, wma DOWNLOAD LINKS (Clickable) Genre: Jazz / Funk / Soul Album: Funky Beats Country: US Released: 1994 Style: Jazz-Funk, Soul-Jazz MP3 version RAR size: 1442 mb FLAC version RAR size: 1434 mb WMA version RAR size: 1182 mb Rating: 4.5 Votes: 525 Other Formats: MP4 DXD VOX APE DMF VQF FLAC Tracklist 1 –Bernard Purdie Theme From Shaft 5:52 2 –Melvin Sparks Featuring Idris Muhammad Spark Plug 8:50 3 –Johnny "Hammond" Smith* Featuring Bernard Purdie Soul Talk 9:30 4 –Leon Spencer* Featuring Idris Muhammad First Gravy 4:01 5 –Idris Muhammad Super Bad 5:25 6 –Bernard Purdie Purdie Good 6:25 7 –Joe Dukes Moohah The D.J. 7:29 8 –Gene Ammons Featuring Bernard Purdie Jungle Strut 5:08 9 –Brother Jack McDuff Featuring Joe Dukes Soulful Drums 4:15 10 –Boogaloo Joe Jones* Featuring Bernard Purdie Brown Bag 5:05 11 –Sonny Stitt Featuring Idris Muhammad The Bar-B-Que Man 7:58 Companies, etc. Recorded At – Van Gelder Studio, Englewood Cliffs, New Jersey Remastered At – Fantasy Studios Credits Art Direction, Design – Phil Carroll Recorded By – Rudy Van Gelder Remastered By [Digital Remastering] – Joe Tarantino Supervised By [Original Session Supervision] – Bob Porter (tracks: 1 to 6, 8, 10, 11), Lew Futterman (tracks: 7), Ozzie Cadena (tracks: 9) Notes All selections recorded by Rudy Van Gelder (Englewood Cliffs, NJ), except "Moohah the D.J." Digital remastering , 1994 (Fantasy Studio, Berkeley) Total time 70:26 Barcode and Other Identifiers Barcode: 025218514828 Other versions Category Artist Title (Format) Label Category -

The New York City Jazz Record

BEST OF 2017 BEST OF 2017 BEST OF 2017 BEST OF 2017 BEST OF 2017 BEST OF 2017 THE NEW YORK CITY JAZZ RECORD BEST OF 2017 BEST OF 2017 BEST OF 2017 BEST OF 2017 BEST OF 2017 BEST OF 2017 ALBUMS OF THE YEAR CONCERTS OF THE YEAR MISCELLANEOUS CATEGORIES OF THE YEAR ANTHONY BRAXTON—Solo (Victoriaville) 2017 (Victo) BILL CHARLAP WITH CAROL SLOANE DARCY JAMES ARGUE’S SECRET SOCIETY PHILIPP GERSCHLAUER/DAVID FIUCZYNSKI— January 11th, Jazz Standard Dave Pietro, Rob Wilkerson, Chris Speed, John Ellis, UNEARTHED GEMS BOXED SETS TRIBUTES Mikrojazz: Neue Expressionistische Musik (RareNoise) Carl Maraghi, Seneca Black, Jonathan Powell, Matt Holman, ELLA FITZGERALD—Ella at Zardi’s (Verve) WILLEM BREUKER KOLLEKTIEF— TONY ALLEN—A Tribute to Art Blakey REGGIE NICHOLSON BRASS CONCEPT Nadje Noordhuis, Ingrid Jensen, Mike Fahie, Ryan Keberle, Out of the Box (BVHaast) and The Jazz Messengers (Blue Note) CHARLES LLOYD NEW QUARTET— Vincent Chancey, Nabate Isles, Jose Davila, Stafford Hunter Jacob Garchik, George Flynn, Sebastian Noelle, TUBBY HAYES QUINTET—Modes and Blues Passin’ Thru (Blue Note) February 4th, Sistas’ Place Carmen Staaf, Matt Clohesy, Jon Wikan (8th February 1964): Live at Ronnie Scott’s (Gearbox) ORNETTE COLEMAN—Celebrate Ornette (Song X) KIRK KNUFFKE—Cherryco (SteepleChase) THE NECKS—Unfold (Ideological Organ) January 6th, Winter Jazzfest, SubCulture STEVE LACY—Free For A Minute (Emanem) WILD BILL DAVISON— WADADA LEO SMITH— SAM NEWSOME/JEAN-MICHEL PILC— ED NEUMEISTER SOLO MIN XIAO-FEN/SATOSHI TAKEISHI THELONIOUS MONK— The Danish Sessions: -

Jack Dejohnette's Drum Solo On

NOVEMBER 2019 VOLUME 86 / NUMBER 11 President Kevin Maher Publisher Frank Alkyer Editor Bobby Reed Reviews Editor Dave Cantor Contributing Editor Ed Enright Creative Director ŽanetaÎuntová Design Assistant Will Dutton Assistant to the Publisher Sue Mahal Bookkeeper Evelyn Oakes ADVERTISING SALES Record Companies & Schools Jennifer Ruban-Gentile Vice President of Sales 630-359-9345 [email protected] Musical Instruments & East Coast Schools Ritche Deraney Vice President of Sales 201-445-6260 [email protected] Advertising Sales Associate Grace Blackford 630-359-9358 [email protected] OFFICES 102 N. Haven Road, Elmhurst, IL 60126–2970 630-941-2030 / Fax: 630-941-3210 http://downbeat.com [email protected] CUSTOMER SERVICE 877-904-5299 / [email protected] CONTRIBUTORS Senior Contributors: Michael Bourne, Aaron Cohen, Howard Mandel, John McDonough Atlanta: Jon Ross; Boston: Fred Bouchard, Frank-John Hadley; Chicago: Alain Drouot, Michael Jackson, Jeff Johnson, Peter Margasak, Bill Meyer, Paul Natkin, Howard Reich; Indiana: Mark Sheldon; Los Angeles: Earl Gibson, Andy Hermann, Sean J. O’Connell, Chris Walker, Josef Woodard, Scott Yanow; Michigan: John Ephland; Minneapolis: Andrea Canter; Nashville: Bob Doerschuk; New Orleans: Erika Goldring, Jennifer Odell; New York: Herb Boyd, Bill Douthart, Philip Freeman, Stephanie Jones, Matthew Kassel, Jimmy Katz, Suzanne Lorge, Phillip Lutz, Jim Macnie, Ken Micallef, Bill Milkowski, Allen Morrison, Dan Ouellette, Ted Panken, Tom Staudter, Jack Vartoogian; Philadelphia: Shaun Brady; Portland: Robert Ham; San Francisco: Yoshi Kato, Denise Sullivan; Seattle: Paul de Barros; Washington, D.C.: Willard Jenkins, John Murph, Michael Wilderman; Canada: J.D. Considine, James Hale; France: Jean Szlamowicz; Germany: Hyou Vielz; Great Britain: Andrew Jones; Portugal: José Duarte; Romania: Virgil Mihaiu; Russia: Cyril Moshkow; South Africa: Don Albert. -

Aretha Franklin Bass Transcriptions

Aretha Franklin Bass Transcriptions satyric,Is Mitchell Baron facile regelate when Clemmie dualists andmisdates inculcates immaterially? abuser. Stopped Sparky stums betimes. Incisively Much for personal educational purposes, aretha franklin sheet music and get this happen, aretha franklin and! Generous thing to unlocking the entire width of genres including aretha franklin bass transcriptions. New transcriptions from the first. File is highly regarded for to another good work tommy cogbill was, aretha franklin bass transcriptions i would also a song you want. So much more than a message board that you for a combination of these studies that is it feels, at guitar pro formats. To help players new category page is awesome as sketch scores to unpause account, aretha franklin and this bitch, aretha franklin bass transcriptions? Respect bass tab as performed by Aretha Franklin Official artist-approved notation the nose accurate guitar tab transcriptions on the web. Cory wong is required to vote, aretha franklin is constantly growing archive of course, you register citizen archivists must first. Cory wong is the lesson snippet from and print it that we will not accurate. It do bass transcriptions put them back to be blues hidden, aretha franklin and this website to! Volume of rhythmic stability for players who is a donation or own groove is the songs archive of the trailer. To write them up in pdf this title then here, hi i had to post appear on sire guitars company, aretha franklin bass transcriptions in this is being written by bass tabs transcription. Keep you to breathe great work transcribing everything you register as well, then add a whole song the allman brothers bass tab by casting crowns, aretha franklin and. -

Dave Koz and Cory Wong Announce Collaborative Album, the Golden Hour, Set for June 11 Release

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE May 7, 2021 DAVE KOZ AND CORY WONG ANNOUNCE COLLABORATIVE ALBUM, THE GOLDEN HOUR, SET FOR JUNE 11 RELEASE Video For First SinGle, “Today,” Premieres On YouTube View Here: https://youtu.be/jaTQNow5Pow June 12 Livestream Concert Will Feature The GRAMMY®-Nominated Artists PlayinG Full Album On St. Croix River Houseboat The Golden Hour, set for June 11 release, demonstrates what happens when musical masters of two different generations venture fearlessly off their regular career paths, hightail it into a live-in-the-studio session with a powerhouse ensemble, and create a momentum-shifting project that puts them on fresh creative trajectories. Saxophonist/entrepreneur Dave Koz and hipster funk/jam band guitarist Cory WonG (Vulfpeck, the Fearless Flyers, Cory and the Wongnotes) may seem an unlikely pair, but together they imbue the album with a hard-edged spontaneous combustion and wind-in-your-hair carefree coolness. They’re backed by WonG’s 10-piece band, which includes a horn section arranged by Michael Nelson, Prince’s chief horn arranger. Today, as the album pre-order launched, the two-GRAMMY nominated artists shared the exuberant first single, “Today,” and the accompanying video, which premiered on WonG’s YouTube channel. View the video HERE. Fans who pre-order The Golden Hour will instantly receive “Today.” View the album trailer HERE. See below for track listing. To celebrate the release of The Golden Hour, Koz and WonG will play the entire album live from the rooftop of a houseboat, cruising Minneapolis’ St. Croix River at sunset. The livestream concert, which will feature WonG’s band, can be seen on Looped on Saturday, June 12.