LCVPPP Final Implementation Report

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

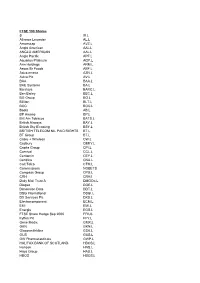

28-June-18 AUSTRALIA 1.Margin 2.Can Go 3.Guaranteed Stock Ticker Rate Short?* Stop Premium

28-June-18 AUSTRALIA 1.Margin 2.Can go 3.Guaranteed Stock Ticker Rate short?* stop premium AGL Energy Limited AGL.AX / AGL AU 5% ✓ 0.3% ALS Limited ALQ.AX / ALQ AU 10% ✓ 1% AMA Group Limited AMA.AX / AMA AU 75% ☎ 1% AMP Limited AMP.AX / AMP AU 5% ✓ 0.3% APA Group APA.AX / APA AU 10% ✓ 0.3% APN Outdoor Group Limited APO.AX / APO AU 10% ✓ 1% APN Property Group Limited APD.AX / APD AU 25% ✘ 1% ARB Corporation Limited ARB.AX / ARB AU 20% ✓ 1% ASX Limited ASX.AX / ASX AU 10% ✓ 0.3% AVJennings Limited AVJ.AX / AVJ AU 25% ✘ 1% AWE Limited AWE.AX / AWE AU 25% ✘ 0.3% Abacus Property Group ABP.AX / ABP AU 20% ✓ 0.7% Accent Group Limited AX1.AX / AX1 AU 25% ✓ 1% Adelaide Brighton Limited ABC.AX / ABC AU 10% ✓ 0.3% Admedus Limited AHZ.AX / AHZ AU 25% ✘ 0.7% Ainsworth Game Technology Limited AGI.AX / AGI AU 25% ✓ 0.7% Alkane Resources Limited ALK.AX / ALK AU 25% ✘ 1% Altium Limited ALU.AX / ALU AU 15% ✓ 1% Altura Mining Limited AJM.AX / AJM AU 25% ☎ 1% Alumina Limited AWC.AX / AWC AU 10% ✓ 0.3% Amcil Limited AMH.AX / AMH AU 25% ✘ 1% Amcor Limited AMC.AX / AMC AU 5% ✓ 0.3% Ansell Limited ANN.AX / ANN AU 10% ✓ 0.3% Ardent Leisure Group AAD.AX / AAD AU 20% ✓ 1% Arena REIT ARF.AX / ARF AU 25% ☎ 1% Argosy Minerals Limited AGY.AX / AGY AU 25% ✘ 1% Aristocrat Leisure Limited ALL.AX / ALL AU 5% ✓ 0.3% Artemis Resources Limited ARV.AX / ARV AU 25% ✘ 1% Asaleo Care Limited AHY.AX / AHY AU 20% ✓ 0.7% Asian Masters Fund Limited AUF.AX / AUF AU 10% ✘ 0.3% Atlas Arteria Limited ALX.AX / ALX AU 10% ✓ 0.3% Aurelia Metals Limited AMI.AX / AMI AU 25% ☎ 1% Aurizon Holdings -

In Transitioning Ulevs to Market by Gavin DJ Harper 2014

The role of Business Model Innovation: in transitioning ULEVs To Market by Gavin D. J. Harper BSc. (Hons) BEng. (Hons) MSc. MSc. MSc. MIET A Thesis Submitted in Fulfilment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy of Cardiff University Logistics and Operations Management Section of Cardiff Business School, Cardiff University 2014 Contents CONTENTS II CANDIDATE’S DECLARATIONS XII LIST OF FIGURES XIII LIST OF TABLES XVIII LIST OF EQUATIONS XIX LIST OF BUSINESS MODEL CANVASES XIX LIST OF ACRONYMS & ABBREVIATIONS XX ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS XXIV ABSTRACT XXVII CHAPTER 1: 1 INTRODUCTION 1 1.1 The Drive towards Sustainable Mobility 1 1.1.1 Sustainability 2 1.1.1.1 Archetypes of Sustainability 4 1.1.1.2 What do we seek to sustain? 5 1.1.1.3 Sustainable Development 6 1.1.1.4 Strategising for Sustainable Development 8 1.1.1.5 The Environmental Footprint of Motor Vehicles 10 1.1.1.6 Resource Scarcity & Peak Oil 12 1.1.1.7 Climate Change & Automobility 13 1.1.1.8 Stern’s Framing of Climate Change 16 1.1.1.9 Accounting for Development 17 1.1.1.10 Population, Development & The International Context 19 1.1.1.11 Sustainable Mobility: A Wicked Problem? 21 1.1.1.12 A Systems View of Sustainability & Automobility 22 1.1.2 Sustainable Consumption & Production 26 1.1.2.1 Mobility: A Priority SCP Sector 26 1.1.2.2 Situating the Car In A Sustainable Transport Hierarchy 27 1.1.2.3 The Role of Vehicle Consumers 29 1.1.2.4 Are Consumers To Blame? 30 1.1.2.5 The Car Industry: Engineering for Consumption? 31 1.1.2.6 ULEVs: Consuming Less? 32 ~ ii ~ 1.1.3 -

Mobile Cranes in the City Low Level Powered Access Annual Rental Rate Guide

www.vertikal.net www.vertikal.net Annual December/January 2011 Vol. 12 issue 9 rental rate guide Mobile cranes in the city Low level powered access A look back at 2010 ...New 150ft JLG boom....New CEO for Terex cranes....TVH bids for Lavendon... On the cover: The new 8ft/2.5m platform height Pop-Up Push 8 in a classic low level access application. & ccontentsa Comment 5 Rental rate 17 Low level access News 6 survey 33 Tadano and Link-Belt end agreement, JLG adds It's that time of year when we report on the 150ft Ultra Boom, Tadano expands in crane, access and telehandler rental rates in the UK and Central/South America, TVH takes a run at 22% (44%) Ireland. Despite a rate Lavendon, Youngman goes self-propelled, 36% Nichols and Riordan leave Terex, New president (4%) bloodbath in the first half Terex Cranes, ALE mega crane completes Thai 42% of last year, rates have (52%) project, Sanghvi Movers to spend $44 million, levelled out or even Platformers Days to skip picked up. Does this mean 2011, New 30 metre 2011 will be a good year? Find Cranes in the city 25 Merlo Roto, Onsite out what you all think as we reveal all in the acquires Statewide, JLG C&A eight page rental rate survey. to fit Firestone tyres to telehandlers, HSE warns Look back - 2010 on RT scissors, Liebherr LR13000 to lift 3,750 review 41 tonnes, New Genie parts depot opens, Platform We take an extensive look at 2010 - the year Baskets for Hydrex, Isoli and HDW team up, that many Snorkel and Leach Lewis sign agreement, Terex would rather Utilities sells fleet, forget. -

List of Global Equities Available with Mubasher

Mubasher Financial Services BSC © Individual Equities List Dec 03, 2012 Country IM Factor (Margin Shorting New positions Mubasher Symbol Description ETF Requirement %) allowed? allowed? Sector ONT.AX 1300 SMILES LTD Australia 20 No Yes DDD.N 3D SYSTEMS CORP US 30 No Yes III.L 3I UK 10 Yes Yes 3IN.L 3I INFRSTTR UK 10 No Yes MMM.N 3M CO US 10 Yes Yes 888.L 888 HLDGS Small Cap & Aim 10 Yes Yes PVD.N A.F.P PROVIDA SA ADR ADR 50 No Yes BAG.L A.G. BARR PLC UK 10 Yes Yes A2.MI A2A SPA Italy 10 Yes Yes AALB.AS AALBERTS INDUSTR Netherlands 10 Yes Yes ARLG.DE AAREAL BANK Germany 10 Yes Yes ABP.AX ABACUS PROP Australia 10 Yes Yes ABB.ST ABB Sweden 10 Yes Yes ABBN.VX ABB LTD Switzerland 10 Yes Yes ABT.N ABBOTT LABORATORIES US 10 Yes Yes ABCA.L ABCAM PLC Small Cap & Aim 25 Yes Yes ABG.MC ABENGOA Spain 10 No Yes ANF.N ABERC FITCH A US 10 No Yes ADN.L ABERDEEN ASSET MANAGEMENT UK 10 Yes Yes ASL.L ABERFORTH SMALLER COMPANIES TST UK 10 Yes Yes ABE.MC ABERTIS Spain 10 No Yes ASAJ.J ABSA GROUP South Africa 10 Yes Yes ACCG.AS ACCELL Netherlands 10 No Yes ACN.N ACCENTURE PLC US 20 Yes Yes ANA.MC ACCIONA SA Spain 10 No Yes ACCP.PA ACCOR France 10 Yes Yes ACCS.L ACCSYS TECHNOLOGIES Small Cap & Aim 25 Yes Yes ACW.N ACCURIDE CORP US 50 Yes Yes ACE.N ACE LTD US 10 No Yes ACN.AX ACER ENERGY Australia 10 No Yes ACX.MC ACERINOX Spain 10 No Yes ACKB.BR ACKERMANS V.HAAR Belgium 10 Yes Yes ACR.AX ACRUX LTD Australia 10 Yes Yes ACS.MC ACS CONS Y SERV Spain 10 No Yes ATLN.VX ACTELION HLDG Switzerland 10 Yes Yes ATVI.OQ ACTIVISION INC NEW US 10 Yes Yes ATU.N ACTUANT CORP -

The Worldwide Construction Equipment Magazine for • Construction • Demolition • Quarrying • Mining

Volume 1 No 3 The worldwide construction equipment magazine for • construction • demolition • quarrying • mining Indepth preview of new products at Bauma 2010 CESAR security scheme expands into Europe Sennebogen goes totally green and adds new cranes Mercedes-Benz announces heavy duty Zetros trucks New scale models and collectibles for plant enthusiasts Workers prepare outdoor exhibits for Bauma 2010 EDITORIAL COMMENT Ideal opportunity for an industry health check As I type these words, Bauma is almost upon us and it promises to be a very good show in terms of new machine launches. Most of this issue is devoted to details of new products being exhibited at the show and many other machines are expected to be unveiled in Munich. Full details and pictures of the newcomers will be provided in the next issues of CP&E. However, seeing new machines is just one reason for visiting a major exhibition like Bauma. Equally important is the opportunity to network and discuss not only developments in technology and better operational practice but also the state of the industry itself. Being able to take an industry health check and assess future business potential is currently more vital than ever given the challenges faced by many companies in the last 18 months due to the global economic crisis. For most construction machinery manufacturers there was never any doubt that they had to be at Bauma. This is the world exhibition for the construction equipment industry and, as it is only held once every three years, being seen to be there, even in these difficult times is essential for all serious contenders. -

Electric Cars Plugged in 2 Deutsche Bank 2009

North America United States Consumer Autos & Auto Parts FITT Research Company Company 3 November 2009 Fundamental, Industry, Thematic, Thought Leading Deutsche Bank's Company Research Product Committee has deemed this work Electric Cars: F.I.T.T. for investors seeking differentiated ideas. In our June 2008 FITT report entitled “Electric Cars: Plugged in”, we suggested that a number of factors, Plugged In 2 including rising oil prices, regulations, and battery technology advancements set the stage for increased electrification of the world’s automobiles. We see implications not only for automakers and traditional auto parts suppliers, but also for raw material producers, electric A mega-theme gains utilities, oil demand, and the global economy. U.S. Autos Research Team momentum Rod Lache Research Analyst (+1) 212 250-5551 Global Markets Research [email protected] Dan Galves Associate Analyst (+1) 212 250-3738 [email protected] Patrick Nolan, CFA Associate Analyst Japan Autos Research Team Kurt Sanger, CFA Research Analyst (+81) 3 5156-6692 [email protected] Takeshi Kitaura Research Associate Europe Autos Research Team Jochen Gehrke Research Analyst (+49) 69 910-31949 [email protected] Gaetan Toulemonde Research Analyst (+33) 1 4495-6668 [email protected] Courtesy of: Better Place Tim Rokossa Research Analyst Korea Autos Research Team Sanjeev Rana Research Analyst (+82) 2 316 8910 [email protected] Stephanie Chang Research Associate China Autos Research Team Vincent Ha, CFA Research Analyst (+852) 2203 6247 [email protected] Deutsche Bank Securities Inc. All prices are those current at the end of the previous trading session unless otherwise indicated. -

Hybrid Electric Vehicle Reaches 100,000 Miles Using an Advanced

March/April 2008 www.BatteryPowerOnline.com Volume 12, Issue 2 Hybrid Electric Vehicle Reaches 100,000 Miles INSIDE Using an Advanced Battery System Battery Power 2008 The UltraBattery combines a supercapacitor and a lead acid battery in a single Conference Preview p 9 unit, creating a hybrid car battery that lasts longer, costs less and is more powerful than current technologies used in hybrid electric vehicles (HEVs). The Battery Power for the Future: UltraBattery test program for HEV applications is Is the Energy Output of the result of an international collaboration. The Batteries Reaching its Limit? battery system was developed by CSIRO in p 10 Australia, built by the Furukawa Battery Company of Japan and tested in the United Kingdom Battery Runtime Demystified through the American-based Advanced Lead-Acid p 13 Battery Consortium. “The UltraBattery is a leap forward for low The Impact of the Recent emission transport and uptake of HEVs,” said DOT Rule p 14 David Lamb, who leads low emissions transport research with the Energy Transformed National Battery Management System Research Flagship. Helps Supermarket Distribution Center Save More Photo courtesy of the “Previous tests show the UltraBattery has a life Advanced Lead-Acid Battery Consortium cycle that is at least four times longer and pro- Than $400,000 p 15 duces 50 percent more power than conventional PRODUCTS & SERVICES battery systems. It’s also about 70 percent cheaper than the batteries currently used in HEVs,” he said. By marrying a conventional fuel-powered engine with a battery to drive an New Batteries electric motor, HEVs achieve the dual environmental benefit of reducing both On the Market p 3 greenhouse gas emissions and fossil fuel consumption. -

2008 Annual Report and Accounts

Optare plc (Formerly known as Darwen Holdings plc) REPORT AND FINANCIAL STATEMENTS for the period ended 31 December 2008 Company Registration No. 06481690 Optare Plc Company Registration No. 06481690 Contents 4 Chairman’s statement 5 Business and financial review 7 Officers and Professional Advisers 9 Directors’ Report 14 Corporate Governance 16 Directors’ Remuneration Report 18 Directors’ Responsibilities in the preparation of Financial Statements 19 Independent Auditor’s Report to the Members of Optare Group plc 21 Consolidated Income Statement 22 Consolidated Balance Sheet 23 Consolidated Cash Flow Statement 24 Consolidated Financial Statements Summary of Significant Accounting Policies 30 Notes to the Consolidated Financial Statements 46 Company Balance Sheet 47 Company Financial Statements Summary of Significant Accounting Policies 48 Notes to the Company Financial Statements 50 Notice of Annual General Meeting Forward-Looking Statements This document contains statements that are not historical facts, but forward-looking statements that involve risks and uncertainties, including the timing and results of vehicles trials, product development and commercialisation risks. These forward looking statements are based on knowledge and information available to the Directors at the date the Directors’ Report was prepared, and are believed to be reasonable at the time of preparation of the Directors’ Report, though are inherently uncertain and difficult to predict. Actual results or experience could differ materially from the forward-looking statements. 3 Optare Plc Chairman’s Statement For Optare 2008 was a year of acquisitions and restructuring, with the benefit of this intense period of review and planning coming through in 2009. Of course the economic climate has had an impact but we have taken appropriate actions to manage this. -

Strategic Options for Azure Dynamics in Hybrid and Battery Electric Vehicle Markets

STRATEGIC OPTIONS FOR AZURE DYNAMICS IN HYBRID AND BATTERY ELECTRIC VEHICLE MARKETS by James Gordon Finlay B. Sc. (Computer Science), University of British Columbia, 1981 PROJECT SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF BUSINESS ADMINISTRATION In the Management of Technology Program of the Faculty of Business Administration © James Gordon Finlay 2012 SIMON FRASER UNIVERSITY Fall 2012 All rights reserved. However, in accordance with the Copyright Act of Canada , this work may be reproduced, without authorization, under the conditions for Fair Dealing . Therefore, limited reproduction of this work for the purposes of private study, research, criticism, review and news reporting is likely to be in accordance with the law, particularly if cited appropriately. Approval Name: James Gordon Finlay Degree: Master of Business Administration Title of Project: Strategic Options for Azure Dynamics in Hybrid and Battery Electric Vehicle Markets Supervisory Committee: __________________________________________________________ Dr. Pek-Hooi Soh Senior Supervisor Associate Professor Faculty of Business Administration __________________________________________________________ Dr. Elicia Maine Second Reader Associate Professor Faculty of Business Administration Date Approved: __________________________________________________________ ii Abstract Azure Dynamics provides electric vehicle powertrain technology to commercial truck fleets in North America and Europe. Azure Dynamics is a firm in distress and fighting for survival, having filed for bankruptcy protection in March 2012. An analysis of commercial trucking markets reviews factors driving vehicle electrification and provides a market segmentation to find segments best suited to Azure’s technology. Porter’s Five Forces methodology is used to assess target market attractiveness and to identify key success factors. An internal analysis of Azure employs a value chain and a VRIO model to identify core competencies. -

WIP Ric Codes

FTSE 100 Shares 3i III.L Alliance Leicester AL.L Amvescap AVZ.L Anglo American AAL.L ANGLO AMERICAN AAL.L Anglo Pacific APF.L Aquarius Platinum AQP.L Arm Holdings ARM.L Assoc Br Foods ABF.L Astrazeneca AZN.L Aviva Plc AV.L BAA BAA.L BAE Systems BA.L Barclays BARC.L Ben Bailey BBC.L BG Group BG.L Billiton BLT.L BOC BOC.L Boots AB.L BP Amoco BP.L Brit Am Tobacco BATS.L British Airways BAY.L British Sky B'casting BSY.L BRITISH TELECOM NIL PAID RIGHTS BT.L BT Group BT.L Cable + Wireless CW.L Cadbury CBRY.L Capita Group CPI.L Carnival CCL.L Centamin CEY.L Centrica CNA.L Colt Telco CTM.L Commissions NOBETS Compass Group CPG.L CRH CRH.I Daily Mail Trust A DMGOa.L Diageo DGE.L Dimension Data DDT.L DSG International DSGI.L DX Services Plc DXS.L Electrocomponent ECM.L EMI EMI.L Energis EGS.L FTSE Share Hedge Sep 2006 FFIU6 Fyffes Plc FFY.L Gene Medix GMX.L GKN GKN.L Glaxosmithkline GSK.L GUS GUS.L GW Pharmaceuticals GWP.L HALIFAX BANK OF SCOTLAND HBOS.L Hanson HNS.L Hays Group HAS.L HBOS HBOS.L Hilton Group (Ladbrokes) LAD.L HSBC HSBA.L ICI ICI.L ICI NIL PAID RIGHTS ICIn.L Imperial Tobacco IMT.L IMPERIAL TOBACCO NIL PAID RIGHTS IMTn.L Inmarsat ISAT.L INNOGY HOLDINGS IOG.L Intercontinental Hotels IHG.L International Power IPR.L INTERNATIONAL POWER IPR.L Invensys ISYS.L iShares FTSE 100 Fund ISF.L IShares MSCI East Europe IEER.L ITV ITV.L Kingfisher KGF.L Land Securities LAND.L Legal + General LGEN.L Legal + General- Nil Paid Rights Issue LGENn.L Lloyds TSB LLOY.L Logicacmg LOG.L Long Interest NOBETS Marks Spencer MKS.L Minor Planet Systems MPS.L -

Admission Document Drawn up in Accordance with the AIM Rules

THIS DOCUMENT IS IMPORTANT AND REQUIRES YOUR IMMEDIATE ATTENTION. If you are in any doubt as to the action you should take, or the contents of this document, you are recommended to seek your own personal financial advice immediately from your stockbroker, bank manager, solicitor, accountant, fund manager or other independent adviser duly authorised under the Financial Services and Markets Act 2000 (as amended) (“FSMA”) who specialises in advising on the acquisition of shares and other securities. If you sell or have sold or otherwise transferred all your Existing Ordinary Shares in Darwen Holdings plc (“Darwen” or the “Company”), you should send this document, together with the accompanying Form of Proxy, to the stockbroker, bank or other agent through whom the sale or transfer was effected, for transmission to the purchaser or transferee. However, such documents should not be forwarded or transmitted in or into the United States of America, Canada, Australia, the Republic of South Africa, the Republic of Ireland or Japan. If you have sold or transferred only part of your holding of Existing Ordinary Shares you should retain these documents. This document comprises an admission document drawn up in accordance with the AIM Rules. This document does not constitute an approved prospectus for the purposes of the Prospectus Rules and contains no offer of transferable securities to the public within the meaning of sections 85 and 102B of FSMA or otherwise. This document has not been, and will not be, approved or examined by or filed with the Financial Services Authority (“FSA”) or by any other authority which could be a competent authority for the purposes of the Prospectus Rules. -

Situational Analysis for the Current Status of the Electric Vehicle Industry

Prepared by For Fleet Technology Partners Natural Resources Canada (Bernard Fleet and James K. Li) Canadian Electric Vehicle Industry and Steering Committee Richard Gilbert Situational Analysis for the Current Status of the Electric Vehicle Industry A Report for Presentation to the Electric Vehicle Industry Steering Committee June 16, 2008 (final edits July 17 th 2008) SITUATION ANALYSIS FOR THE CURRENT STATE OF ELECTRIC VEHICLE TECHNOLOGY TABLE OF CONTENTS A. E XECUTIVE SUMMARY .................................................................................................................... 3 B. T IMELINESS OF A FOCUS ON EV T ECHNOLOGY DEVELOPMENT .......................................................... 4 C. O VERVIEW OF MAJOR STUDIES AVAILABLE SINCE 2005................................................................... 7 Documents noted in the proposal or added by the project team (other than the market forecasts noted below)........................................................................................................................................................ 8 Documents identified by members of the Steering Committee ................................................................. 8 Electric vehicle market forecasts............................................................................................................... 9 Electric vehicle battery commercial market forecasts.............................................................................. 10 D. B RIEF OVERVIEW OF BATTERY TECHNOLOGY AND PERFORMANCE