The Professor & the Parson

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Chronologically Lewis Joel D

Chronologically Lewis Joel D. Heck All notes are done in the present tense of the verb for consistency. Start and end dates of term are those officially listed in the Oxford calendar. An email from Robin Darwall-Smith on 11/26/2008 explains the discrepancies between official term dates and the notes of C. S. Lewis in his diary and letters: “Term officially starts on a Thursday, but then 1st Week (out of 8) starts on the following Sunday (some might say Saturday, but it ought to be Sunday). The week in which the start of term falls is known now as „0th Week‟. I don‟t know how far back that name goes, but I‟d be surprised if it wasn‟t known in Lewis‟s day. The system at the start of term which I knew in the 1980s - and which I guess was there in Lewis‟s time too - was that the undergraduates had to be in residence by the Thursday of 0th Week; the Friday was set aside for start of term Collections (like the ones memorably described in Lewis‟s diary at Univ.!), and for meetings with one‟s tutors. Then after the weekend lectures and tutorials started in earnest on the Monday of 1st Week.” Email from Robin Darwall-Smith on 11/27/2008: “The two starts to the Oxford term actually have names. There‟s the start of term, in midweek, and then the start of „Full Term‟, on the Sunday - and is always Sunday. Lectures and tutorials start up on the following day. -

NEWS St Daylight Saving Starts Sunday 31 March Remember, the Clocks Go Back at 0100 Hours on Sunday 31 March 2019

ALL SAINTS 31st March 2019 Lent 4 Mothering Sunday (Laetare Sunday) NEWS st Daylight Saving Starts Sunday 31 March Remember, the clocks go back at 0100 hours on Sunday 31 March 2019 Ian Yemm As you are aware, Ian Yemm has been recommended for ordination training in the Province of the Church in Wales. Bishop June Osborne of the Diocese of Llandaff is has organised for him to the St Padarn’s Institute in Cardiff for a year of formation starting in September 2019. He will be based in a parish context from the outset and he will continue in that parish for his Curacy. Consequently today is the final ‘formal’ day that Ian is with us in his role as an LLM (Licensed Lay Minister). However, I have absolutely no doubt that he will be back amongst us soon as a guest deacon then priest. Ian and Bernhard have called All Saints their spiritual home and have been part of our worshipping community since 2004. Please keep Ian and Bernhard in your prayers and we look forward to welcoming both back in the not too distant future. Posy Making – Saturday 30th March at 10.00am Sunday is Mothering Sunday. A group of Posy Makers will collect together in church on Saturday morning at 10.00 am to create posies ready for Sunday worship. Posies will be distributed as part of the All Ages Service and at the start of the Parish Mass. Mothering Sunday Don’t forget – no Joint Service this Mothering Sunday…….. Mothering Sunday Services on Sunday 31st March are All Ages at 9.30am and Parish Mass at 11.00am. -

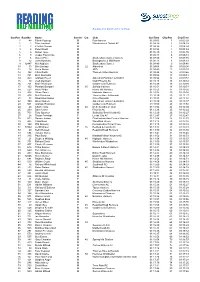

Sunday 21St March 2010 10:05Am Gunpos Raceno Name Gender Cat Club Guntime Chippos Chiptime 1 48 Edwin Kipyego M Run-Fast.Net 01

Sunday 21st March 2010 10:05am GunPos RaceNo Name Gender Cat Club GunTime ChipPos ChipTime 1 48 Edwin Kipyego M Run-fast.net 01:03:03 1 01:03:03 2 2 Toby Lambert M Winchester & District AC 01:04:29 2 01:04:29 3 3 Ezekiel Cherop M 01:04:34 3 01:04:34 4 8 Peter Nowill M 01:04:58 4 01:04:59 5 4 Simon Tonui M 01:05:30 5 01:05:30 6 9 Jesper Faurschou M 01:05:44 6 01:05:44 7 6 Gareth Price M Shaftesbury Barnet Harriers 01:07:56 7 01:07:55 8 12 John Hutchins M Basingstoke & Mid Hants 01:08:14 8 01:08:13 9 12447 Neil Addison M Shaftesbury Barnet 01:08:40 9 01:08:40 10 33 Ben Lindsay M 22 Aldershot 01:09:08 10 01:09:08 11 18 Kevin Quinn M AFD 01:09:40 11 01:09:39 12 192 Chris Smith M Thames Valley Harriers 01:09:48 12 01:09:46 13 741 Bryn Reynolds M 01:09:52 13 01:09:51 14 469 Graham Breen M Aldershot Farnham & District 01:09:54 14 01:09:52 15 14 Josh Guilmant M Club Phoenix AC 01:10:13 15 01:10:12 16 701 Mark Dickinson M Garden City Runners 01:10:39 16 01:10:38 17 100 Pumlani Bangani M 35 Salford Harriers 01:10:51 18 01:10:51 18 552 Brian Wilder M Herne Hill Harriers 01:10:53 17 01:10:50 19 406 Glenn Saqui M Highgate Harriers 01:10:58 19 01:10:58 20 418 Neil Chisholm M Thames Hare & Hounds 01:11:29 20 01:11:27 21 34 Stuart Huntington M City of Norwich 01:11:33 21 01:11:32 22 399 Brian Wakem M Aldershot Farnham & District 01:11:39 22 01:11:37 23 501 Graham Robinson M Garden City Runners 01:11:59 23 01:11:58 24 24 Charlie Cilia M 40 Mellieha Athletic Club 01:12:04 24 01:12:04 25 209 Dave Carter M Phoenix AC 01:12:26 25 01:12:24 26 703 Toby Spencer -

The Year 1950 (182)

The Year 1950 (182) Summary: In 1950, The Lion, the Witch and the Wardrobe, the first of the Chronicles of Narnia, was published on October 16 in England and on November 7 in America. Jack was in the midst of writing the Chronicles, and Roger Lancelyn Green was reading them. Jack received his first letter from Joy Gresham on January 10. The Inklings were meeting regularly on Tuesdays, but no longer on Thursdays. Jack was receiving gifts of food, stationery, etc., during post-war rationing from Americans Edward Allen, Vera Mathews, Dr. Warfield Firor, and Mrs. Frank Jones (and perhaps Nathan Starr). Jack declined Firor’s invitation to come to America. On February 13, Jack debated Mr. Archibald Robertson of the Rationalist Press Association on “Grounds for Disbelief in God” at the Oxford Socratic Club. Anthony Flew spoke at the Socratic Club in May. In April, the Revd. Duff arrived to try to interest Jack in a home Mission called the Industrial Christian Fellowship, and Mrs. Moore was taken to a nursing home called Restholme. Jack began daily visits to see Mrs. Moore, which continued until her death in January 1951. Daphne Harwood contracted and then died from cancer. June (Jill) Flewett, one of the World War II evacuees who stayed at the Kilns, was married on September 4, which Warren attended. Grace Havard, wife of Humphrey Havard, died on September 10. The famous Firor Ham Feast took place at 7:30 p.m. at Jack’s rooms on September 19. In December Sheldon Vanauken began corresponding with Jack. Jack writes “What Are We to Make of Jesus Christ?” In this year Jack perhaps writes a poem on the shallowness of modern life, entitled “Finchley Avenue.” A second edition of Dymer is published in this year with a Preface by Jack. -

Chronologically Lewis Joel D

Chronologically Lewis Joel D. Heck 1950 In this year Dent reprints Lewis’s long narrative poem Dymer. Jack writes “What Are We to Make of Jesus Christ?” In this year Jack perhaps writes a poem on the shallowness of modern life, entitled “Finchley Avenue. January 1 Sunday. Jack writes a letter of recommendation for former student Frank Goodridge. January 3 Tuesday. Jack writes to George Hamilton. January 7 Saturday. Jack writes to Nathan Starr, who seems to have sent a gift. Jack spends the weekend at Malvern. January 9 Monday. Jack writes to his goddaughter Sarah Neylan about the many letters he has to answer after just returning from Malvern. Jack writes to Rhona Bodle about Charles Williams using the words “holy luck.” January 10 Tuesday. Hilary Term begins. Jack receives his first letter from Joy Davidman Gresham.1 The Inklings meet in the morning at the Eagle and Child and drink to Nathan Starr’s health. January 12 Thursday. Jack writes to Sister Penelope about her book rejections and a book he is planning to write with Tolkien.2 January 14 Saturday. Hilary Term begins.3 January 16 Monday. Maureen comes to the Kilns in the evening. January 17 Tuesday. Jack meets Warren in the Cloister at Magdalen and tells him that their dog Bruce has died, but actually he has been euthanized.4 January 23 Monday. The Socratic Club meets on “The Nature of Faith” with J. P. Hickinbotham and E. L. Mascall speaking. January 24 Tuesday. Jack writes to Edward Allen about his recent gift and the current election campaign. -

Notable People Buried in Oxford Cemeteries

NOTABLE PEOPLE BURIED IN OXFORD CEMETERIES NAME BORN DIED CEMETERY REMARKS Sir Charles 1833 1896 Wolvercote Sir Charles did not inherit the title 'Sir'. It was awarded later, as a Umpherston result of his achievements. He was not a member of the aristocracy Aitchison and he did not go to one of our famous public schools. He attended the local High School in Edinburgh Scotland, where he was born, and then went to Edinburgh University, where he was considered a bright student. He first showed himself to be exceptional at the age of 23, when he took the competitive examination for the Indian Civil Service, as it was then called. There were 113 candidates for only 20 places. Sir Charles came 5th overall. He first came out to the Sub-continent at the age of 24, arriving in Calcutta in September 1856, as a Junior Civil Servant. The next year he was transferred to the Punjab, and was posted to Lahore in March 1858, when he was 26. In the next 20 years, he was gradually promoted, moving upwards through the ranks. He also wrote several books. His most extensive work was a collection of treaties, engagements and Sanads, which eventually spread to eleven volumes. In 1878 he was disappointed to be transferred to Burma, where he felt home-sick for the Punjab. Sir Charles therefore saw this great ambition of his achieved a year befor the end of his term as Lieutenant-Governor. In 1888 he finally retired to England. By this time, he was in a fairly poor state of health, and he eventually died in 1896, at the age of 64. -

Congregationalism in Oxford the Growth and Development of Congregational Churches in and Around the City of Oxford Since 1653

Congregationalism in Oxford The growth and development of Congregational Churches in and around the city of Oxford since 1653 by Michael Hopkins A thesis submitted to The University of Birmingham for the degree of MASTER OF PHILOSOPHY Department of Theology and Religion School of Historical Studies The University of Birmingham January 2010 1 University of Birmingham Research Archive e-theses repository This unpublished thesis/dissertation is copyright of the author and/or third parties. The intellectual property rights of the author or third parties in respect of this work are as defined by The Copyright Designs and Patents Act 1988 or as modified by any successor legislation. Any use made of information contained in this thesis/dissertation must be in accordance with that legislation and must be properly acknowledged. Further distribution or reproduction in any format is prohibited without the permission of the copyright holder. ABSTRACT This thesis contends that the growth and development of Congregationalism in Oxford was different from elsewhere because of the presence of both the University of Oxford and Mansfield College. It explores fully the progress of Congregationalism in Oxford during the three hundred and fifty years from the Puritans in the English Commonwealth until the beginning of the twenty-first century. It considers these developments in the light of the national background and explains how they are distinctive, rather than representative, through the story of the New Road Meeting House, George Street and Summertown Congregational Churches in particular, and the other suburban and village Congregational chapels in contrast to other towns and cities with Congregational colleges. -

July-Aug Chronicle

July / August 2017 1 From the Editors Sally Hemsworth and Nicki Stevens We do hope you enjoy the summer edition of The Chronicle. Please consider renewing your subscription. The cost will remain the same as last year - £4 for an A5 copy, and £5 for anA4 copy. You may wish to encourage other people to take out subscriptions. Order forms are available in both churches - Chris Knevett has agreed to collect the slips from St James end of the Parish, and Norah Shallow will continue to collect from St Francis. We were interested to see the subject of the Mothers’ Union July meeting –holiday reading. Perhaps there will be some interesting Books of the Month in future editions of The Chronicle?? Last month we had an interesting account of Lesley Williams’ holiday in the Falkland Islands. Maybe you are not going that far afield – but we would love to hear about other people’s activities and holidays. The Dates to Remember gives details of lots of church events over the next couple of months – so enjoy the summer. But please remember to fill in the slip to order the Chronicle for the next year – so that you can keep in touch with church activities and the activities of the church congregation. Please note the earlier date for articles – due to holidays. We do hope lots of articles will be submitted for inclusion – different things help to make the Chronicle interesting. GARDENING PARTY THE GILDAY FAMILY RE- HELP REQUIRED – TURNS TO OXFORDSHIRE COME AND BOOST THE NUMBERS Many of you will remember Patrick and Lydia LOOKING AFTER THE Gilday, who married at St Francis Church AREA AROUND ST while Patrick was in training for the priest- JAMES CHURCH AND hood. -

Blackbird Leys a Thirty Year History

Blackbird Leys A thirty year history And a celebration of forty years of The Church of the Holy Family The story of an ecumenical church growing out of nothing on a new council estate built in the 60’s. 1 Foreword At the beginning of 1990 it was suggested that a history should be written up ready for the 30th Anniversary of Holy Family Church in June that year. Jack Argent, the Chairman of the Church Committee, and Church Warden, for most of those 30 years was planning to do this, but with his sudden death in March 1990 nothing had been started. As I have lived on the estate for 32 years, and been a member of Holy Family Church since it first began, I was asked to produce an article for the Church Magazine. It proved to be such and interesting task looking through the folders of letters, Minutes and Magazines that I offered to write up the history in more detail. The following I hope is a glimpse of life on an outer city estate. Dorothy Fox, Oxford, 1990. Foreword to 2005 edition This year we are celebrating forty years of Holy Family Church since it’s dedication on 10th April 1965. This anniversary and the associated celebrations prompted a number of people to regret that Dorothy’s history was no longer in print so it was decided to reprint the text with a few new illustrations. As part of our celebrations a number of people have written appreciations of Holy Family Church for the Church Magazine. -

ND Sept 2017.Pdf

FOLKESTONE Kent , St Peter on the East Cliff A Forward in Faith Parish under the episcopal care of the Bishop of Richbor - ough . Sunday: 8am Low Mass, 10.30am Solemn Mass. Evensong 6pm. Weekdays - Low Mass: Tues 7pm, Thur 12 noon. Contact Fa - parish directory ther David Adlington or Father David Goodburn SSC - tel: 01303 254472 http://stpetersfolk.church BATH Bathwick Parishes , St.Mary’s (bottom of Bathwick Hill), BURGH-LE-MARSH Ss Peter & Paul , (near Skegness) PE24 e-mail: [email protected] St.John's (opposite the fire station) Sunday - 9.00am Sung Mass at 5DY A resolution parish in the care of the Bishop of Richborough . GRIMSBY St Augustine , Legsby Avenue Lovely Grade II St.John's, 10.30am at St.Mary's 6.00pm Evening Service - 1st, Sunday Services: 9.30am Sung Mass (& Junior Church in term Church by Sir Charles Nicholson. A Forward in Faith Parish under 3rd &5th Sunday at St.Mary's and 2nd & 4th at St.John's. Con - time) 6.00pm Sung Evensong (BCP) Weekday Mass Thursdays Bishop of Richborough . Sunday: Parish Mass 9.30am, Solemn tact Fr.Peter Edwards 01225 460052 or www.bathwick - 9am. Other services as announced. All visitors very welcome. Evensong and Benediction 6pm (First Sunday). Weekday Mass: parishes.org.uk Rector: Canon Terry Steele, The Rectory, Glebe Rise, Burgh-le- Mon 7.00pm, Wed 9.30am, Sat 9.30am. Parish Priest: Fr.Martin Marsh. PE245BL. Tel 01754810216 or 07981878648 email: 07736 711360 BEXHILL on SEA St Augustine’s , Cooden Drive, TN39 3AZ [email protected] Sunday: Mass at 8am, Parish Mass with Junior Church at1 0am.