Big Shot's Funeral

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

China Perspectives, 55 | September - October 2004 Claire Shen Hsiu-Chen, L’Encre Et L’Ecran

China Perspectives 55 | september - october 2004 Varia Claire Shen Hsiu-chen, L’Encre et l’Ecran. A la recherche de la stylistique cinématographique chinoise, Hou Hsiao-hsien et Zhang Yimou (Ink and the Screen : In Search of Chinese Film Stylistics, Hou Hsiao- hsien and Zhang Yimou) Taipei, Ricci Institute in Taipei, Variétés sinologiques, New Series 91, 2002, 124 p. Bérénice Reynaud Édition électronique URL : http://journals.openedition.org/chinaperspectives/424 DOI : 10.4000/chinaperspectives.424 ISSN : 1996-4617 Éditeur Centre d'étude français sur la Chine contemporaine Édition imprimée Date de publication : 1 octobre 2004 ISSN : 2070-3449 Référence électronique Bérénice Reynaud, « Claire Shen Hsiu-chen, L’Encre et l’Ecran. A la recherche de la stylistique cinématographique chinoise, Hou Hsiao-hsien et Zhang Yimou (Ink and the Screen : In Search of Chinese Film Stylistics, Hou Hsiao-hsien and Zhang Yimou) », China Perspectives [En ligne], 55 | september - october 2004, mis en ligne le 28 novembre 2006, consulté le 24 septembre 2020. URL : http:// journals.openedition.org/chinaperspectives/424 ; DOI : https://doi.org/10.4000/chinaperspectives. 424 Ce document a été généré automatiquement le 24 septembre 2020. © All rights reserved Claire Shen Hsiu-chen, L’Encre et l’Ecran. A la recherche de la stylistique c... 1 Claire Shen Hsiu-chen, L’Encre et l’Ecran. A la recherche de la stylistique cinématographique chinoise, Hou Hsiao-hsien et Zhang Yimou (Ink and the Screen : In Search of Chinese Film Stylistics, Hou Hsiao-hsien and Zhang Yimou) Taipei, Ricci Institute in Taipei, Variétés sinologiques, New Series 91, 2002, 124 p. Bérénice Reynaud NOTE DE L’ÉDITEUR Translated from the French original by Michael Black 1 Reading Claire Shen Hsiu-chen gave me the impression several times of discovering a kindred spirit, so closely does the first part of her book confirm some of my analyses1. -

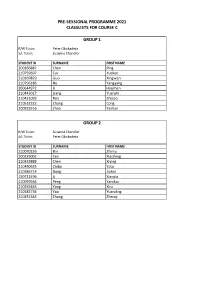

Classlists for C by Group

PRE-SESSIONAL PROGRAMME 2021 CLASSLISTS FOR COURSE C GROUP 1 R/W Tutor: Peter Obukadeta S/L Tutor: Suzanne Chandler STUDENT ID SURNAME FIRST NAME 200166887 Chen Ping 210759697 Cui Yuekun 210169829 Guo Xingwen 210796186 Hu Yangyang 200644972 Li Haozhan 210443017 Liang Yuanzhi 210421093 Ren Zhijiao 210532322 Zhang Cong 200925516 Zhao Yashan GROUP 2 R/W Tutor: Suzanne Chandler S/L Tutor: Peter Obukadeta STUDENT ID SURNAME FIRST NAME 210070226 Bin Zhimu 200329002 Cen Xiaofeng 210333888 Chen Xiying 210450635 Chiba Yota 210386714 Dong Jiahui 190711496 Li Xiaoxia 210059564 Peng Yanduo 210255465 Yang Xiru 210182736 Yao Yuanding 210252383 Zhang Zhenqi GROUP 3 R/W Tutor: Mark Heffernan S/L Tutor: Alan Hart STUDENT ID SURNAME FIRST NAME 210154386 Cai Zhenping 210462580 Ge Xiaodan 210648276 Hirunkhajonrote Kullanut 210182714 Huang Siwei 200141563 Kung Tzu-Ning 200305176 Punsri Punnatorn 200664774 Sayin Humeyra 210186446 Shehata Omar 171003323 Tutberidze Tea 200134624 Wang Shuo 200136019 Xu Ming 200278696 Yan Jiaxin 210357851 Yuan Lai 210029165 Zhang Anru 210219777 Zhang Jiasheng GROUP 4 R/W Tutor: Sherin White S/L Tutor: Alan Hart STUDENT ID SURNAME FIRST NAME 200247588 Chen Chong 200349343 Li Cheng 210622933 Liang Wenxuan 210219618 Liu Huiyuan 210376298 Liu Zeyu 210237531 Mei Lyuke 200132620 Qi Shuyu 210681907 Wang Handuo 200015356 Wu Zhuoyue 200071994 Xie Kaijun GROUP 5 R/W Tutor: Chukwudi Dozie S/L Tutor: Nora Mikso STUDENT ID SURNAME FIRST NAME 210563304 Almalek Ahmed 210186309 Altamimi Saud 210251102 Cheng Han-Yu 210349823 Guo Wenyuan 210239409 -

New China's Forgotten Cinema, 1949–1966

NEW CHINA’S FORGOTTEN CINEMA, 1949–1966 More Than Just Politics by Greg Lewis Several years ago when planning a course on modern Chinese history as seen through its cinema, I realized or saw a significant void. I hoped to represent each era of Chinese cinema from the Leftist movement of the 1930s to the present “Sixth Generation,” but found most available subtitled films are from the post-1978 reform period. Films from the Mao Zedong period (1949–76) are particularly scarce in the West due to Cold War politics, including a trade embargo and economic blockade lasting more than two decades, and within the arts, a resistance in the West to Soviet- influenced Socialist Realism. wo years ago I began a project, Translating New China’s Cine- Phase One. Economic Recovery, ma for English-Speaking Audiences, to bring Maoist Heroic Revolutionaries, and Workers, T cinema to students and educators in the US. Several genres Peasants, and Soldiers (1949–52) from this era’s cinema are represented in the fifteen films we have Despite differences in perspective on Maoist cinema, general agree- subtitled to date, including those of heroic revolutionaries (geming ment exists as to the demarcation of its five distinctive phases (four yingxiong), workers-peasants-soldiers (gongnongbing), minority of which are represented in our program). The initial phase of eco- peoples (shaoshu minzu), thrillers (jingxian), a children’s film, and nomic recovery (1949–52) began with the emergence of the Dong- several love stories. Collectively, these films may surprise teachers bei (later Changchun) Film Studio as China’s new film capital. -

19.05.21 Notable Industry Recognition Awards List • ADC Advertising

19.05.21 Notable Industry Recognition Awards List • ADC Advertising Awards • AFI Awards • AICE & AICP (US) • Akil Koci Prize • American Academy of Arts and Letters Gold Medal in Music • American Cinema Editors • Angers Premier Plans • Annie Awards • APAs Awards • Argentine Academy of Cinematography Arts and Sciences Awards • ARIA Music Awards (Australian Recording Industry Association) Ariel • Art Directors Guild Awards • Arthur C. Clarke Award • Artios Awards • ASCAP awards (American Society of Composers, Authors and Publishers) • Asia Pacific Screen Awards • ASTRA Awards • Australian Academy of Cinema and Television Arts (AACTS) • Australian Production Design Guild • Awit Awards (Philippine Association of the Record Industry) • BAA British Arrow Awards (British Advertising Awards) • Berlin International Film Festival • BET Awards (Black Entertainment Television, United States) • BFI London Film Festival • Bodil Awards • Brit Awards • British Composer Awards – For excellence in classical and jazz music • Brooklyn International Film Festival • Busan International Film Festival • Cairo International Film Festival • Canadian Screen Awards • Cannes International Film Festival / Festival de Cannes • Cannes Lions Awards • Chicago International Film Festival • Ciclope Awards • Cinedays – Skopje International Film Festival (European First and Second Films) • Cinema Audio Society Awards Cinema Jove International Film Festival • CinemaCon’s International • Classic Rock Roll of Honour Awards – An annual awards program bestowed by Classic Rock Clio -

French Names Noeline Bridge

names collated:Chinese personal names and 100 surnames.qxd 29/09/2006 13:00 Page 8 The hundred surnames Pinyin Hanzi (simplified) Wade Giles Other forms Well-known names Pinyin Hanzi (simplified) Wade Giles Other forms Well-known names Zang Tsang Zang Lin Zhu Chu Gee Zhu Yuanzhang, Zhu Xi Zeng Tseng Tsang, Zeng Cai, Zeng Gong Zhu Chu Zhu Danian Dong, Zhu Chu Zhu Zhishan, Zhu Weihao Jeng Zhu Chu Zhu jin, Zhu Sheng Zha Cha Zha Yihuang, Zhuang Chuang Zhuang Zhou, Zhuang Zi Zha Shenxing Zhuansun Chuansun Zhuansun Shi Zhai Chai Zhai Jin, Zhai Shan Zhuge Chuko Zhuge Liang, Zhan Chan Zhan Ruoshui Zhuge Kongming Zhan Chan Chaim Zhan Xiyuan Zhuo Cho Zhuo Mao Zhang Chang Zhang Yuxi Zi Tzu Zi Rudao Zhang Chang Cheung, Zhang Heng, Ziche Tzuch’e Ziche Zhongxing Chiang Zhang Chunqiao Zong Tsung Tsung, Zong Xihua, Zhang Chang Zhang Shengyi, Dung Zong Yuanding Zhang Xuecheng Zongzheng Tsungcheng Zongzheng Zhensun Zhangsun Changsun Zhangsun Wuji Zou Tsou Zou Yang, Zou Liang, Zhao Chao Chew, Zhao Kuangyin, Zou Yan Chieu, Zhao Mingcheng Zu Tsu Zu Chongzhi Chiu Zuo Tso Zuo Si Zhen Chen Zhen Hui, Zhen Yong Zuoqiu Tsoch’iu Zuoqiu Ming Zheng Cheng Cheng, Zheng Qiao, Zheng He, Chung Zheng Banqiao The hundred surnames is one of the most popular reference Zhi Chih Zhi Dake, Zhi Shucai sources for the Han surnames. It was originally compiled by an Zhong Chung Zhong Heqing unknown author in the 10th century and later recompiled many Zhong Chung Zhong Shensi times. The current widely used version includes 503 surnames. Zhong Chung Zhong Sicheng, Zhong Xing The Pinyin index of the 503 Chinese surnames provides an access Zhongli Chungli Zhongli Zi to this great work for Western people. -

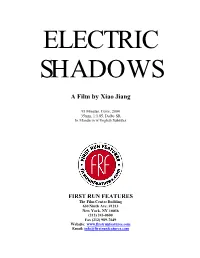

Electric Shadows PK

ELECTRIC SHADOWS A Film by Xiao Jiang 95 Minutes, Color, 2004 35mm, 1:1.85, Dolby SR In Mandarin w/English Subtitles FIRST RUN FEATURES The Film Center Building 630 Ninth Ave. #1213 New York, NY 10036 (212) 243-0600 Fax (212) 989-7649 Website: www.firstrunfeatures.com Email: [email protected] ELECTRIC SHADOWS A film by Xiao Jiang Short Synopsis: From one of China's newest voices in cinema and new wave of young female directors comes this charming and heartwarming tale of a small town cinema and the lifelong influence it had on a young boy and young girl who grew up with the big screen in that small town...and years later meet by chance under unusual circumstances in Beijing. Long Synopsis: Beijing, present. Mao Dabing (‘Great Soldier’ Mao) has a job delivering bottled water but lives for his nights at the movies. One sunny evening after work he’s racing to the movie theatre on his bike when he crashes into a pile of bricks in an alleyway. As he’s picking himself up, a young woman who saw the incident picks up a brick and hits him on the head... He awakens in the hospital with his head bandaged. The police tell him that he’s lost his job, and that his ex-boss expects him to pay for the wrecked bicycle. By chance he sees the young woman who hit him and angrily remonstrates with her. But she seems not to hear him, and hands him her apartment keys and a note asking him to feed her fish. -

Is Shuma the Chinese Analog of Soma/Haoma? a Study of Early Contacts Between Indo-Iranians and Chinese

SINO-PLATONIC PAPERS Number 216 October, 2011 Is Shuma the Chinese Analog of Soma/Haoma? A Study of Early Contacts between Indo-Iranians and Chinese by ZHANG He Victor H. Mair, Editor Sino-Platonic Papers Department of East Asian Languages and Civilizations University of Pennsylvania Philadelphia, PA 19104-6305 USA [email protected] www.sino-platonic.org SINO-PLATONIC PAPERS FOUNDED 1986 Editor-in-Chief VICTOR H. MAIR Associate Editors PAULA ROBERTS MARK SWOFFORD ISSN 2157-9679 (print) 2157-9687 (online) SINO-PLATONIC PAPERS is an occasional series dedicated to making available to specialists and the interested public the results of research that, because of its unconventional or controversial nature, might otherwise go unpublished. The editor-in-chief actively encourages younger, not yet well established, scholars and independent authors to submit manuscripts for consideration. Contributions in any of the major scholarly languages of the world, including romanized modern standard Mandarin (MSM) and Japanese, are acceptable. In special circumstances, papers written in one of the Sinitic topolects (fangyan) may be considered for publication. Although the chief focus of Sino-Platonic Papers is on the intercultural relations of China with other peoples, challenging and creative studies on a wide variety of philological subjects will be entertained. This series is not the place for safe, sober, and stodgy presentations. Sino- Platonic Papers prefers lively work that, while taking reasonable risks to advance the field, capitalizes on brilliant new insights into the development of civilization. Submissions are regularly sent out to be refereed, and extensive editorial suggestions for revision may be offered. Sino-Platonic Papers emphasizes substance over form. -

Annual Report 2019/20

Annual Report 2019 – 2020 TE TUMU WHAKAATA TAONGA | NEW ZEALAND FILM COMMISSION Annual Report – 2019/20 1 G19 REPORT OF THE NEW ZEALAND FILM COMMISSION for the year ended 30 June 2020 In accordance with Sections 150 to 157 of the Crown Entities Act 2004, on behalf of the New Zealand Film Commission we present the Annual Report covering the activities of the NZFC for the 12 months ended 30 June 2020. Kerry Prendergast David Wright CHAIR BOARD MEMBER Image: Daniel Cover Image: Bellbird TE TUMU WHAKAATA TAONGA | NEW ZEALAND FILM COMMISSION Annual Report – 2019/20 1 NEW ZEALAND FILM COMMISSION ANNUAL REPORT 2019/20 CONTENTS INTRODUCTION COVID-19 Our Year in Review ••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••• 4 The screen industry faced unprecedented disruption in 2020 as a result of COVID-19. At the time the country moved to Alert Level 4, 47 New Zealand screen productions were in various stages Chair’s Introduction •••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••• 6 of production: some were near completion and already scheduled for theatrical release, some in post-production, many in production itself and several with offers of finance gearing up for CEO Report •••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••• 7 pre-production. Work on these projects was largely suspended during the lockdown. There were also thousands of New Zealand crew working on international productions who found themselves NZFC Objectives/Medium Term Goals •••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••• 8 without work while waiting for production to recommence. NZFC's Performance Framework ••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••• 8 COVID-19 also significantly impacted the domestic box office with cinema closures during Levels Vision, Values and Goals ••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••• 9 3 and 4 disrupting the release schedule and curtailing the length of time several local features Activate high impact, authentic and culturally significant Screen Stories ••••••••••••• 11 played in cinemas. -

Inscriptional Records of the Western Zhou

INSCRIPTIONAL RECORDS OF THE WESTERN ZHOU Robert Eno Fall 2012 Note to Readers The translations in these pages cannot be considered scholarly. They were originally prepared in early 1988, under stringent time pressures, specifically for teaching use that term. Although I modified them sporadically between that time and 2012, my final year of teaching, their purpose as course materials, used in a week-long classroom exercise for undergraduate students in an early China history survey, did not warrant the type of robust academic apparatus that a scholarly edition would have required. Since no broad anthology of translations of bronze inscriptions was generally available, I have, since the late 1990s, made updated versions of this resource available online for use by teachers and students generally. As freely available materials, they may still be of use. However, as specialists have been aware all along, there are many imperfections in these translations, and I want to make sure that readers are aware that there is now a scholarly alternative, published last month: A Source Book of Ancient Chinese Bronze Inscriptions, edited by Constance Cook and Paul Goldin (Berkeley: Society for the Study of Early China, 2016). The “Source Book” includes translations of over one hundred inscriptions, prepared by ten contributors. I have chosen not to revise the materials here in light of this new resource, even in the case of a few items in the “Source Book” that were contributed by me, because a piecemeal revision seemed unhelpful, and I am now too distant from research on Western Zhou bronzes to undertake a more extensive one. -

Warriors As the Feminised Other

Warriors as the Feminised Other The study of male heroes in Chinese action cinema from 2000 to 2009 A thesis submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Chinese Studies at the University of Canterbury by Yunxiang Chen University of Canterbury 2011 i Abstract ―Flowery boys‖ (花样少年) – when this phrase is applied to attractive young men it is now often considered as a compliment. This research sets out to study the feminisation phenomena in the representation of warriors in Chinese language films from Hong Kong, Taiwan and Mainland China made in the first decade of the new millennium (2000-2009), as these three regions are now often packaged together as a pan-unity of the Chinese cultural realm. The foci of this study are on the investigations of the warriors as the feminised Other from two aspects: their bodies as spectacles and the manifestation of feminine characteristics in the male warriors. This study aims to detect what lies underneath the beautiful masquerade of the warriors as the Other through comprehensive analyses of the representations of feminised warriors and comparison with their female counterparts. It aims to test the hypothesis that gender identities are inventory categories transformed by and with changing historical context. Simultaneously, it is a project to study how Chinese traditional values and postmodern metrosexual culture interacted to formulate Chinese contemporary masculinity. It is also a project to search for a cultural nationalism presented in these films with the examination of gender politics hidden in these feminisation phenomena. With Laura Mulvey‘s theory of the gaze as a starting point, this research reconsiders the power relationship between the viewing subject and the spectacle to study the possibility of multiple gaze as well as the power of spectacle. -

Download Press Release

Press Release Berlinale Special 2011 As part of the Official Programme, this year’s Berlinale Special will be presenting recent works by contemporary filmmakers and film portraits of outstanding personalities. In memory of Italian director Mario Monicelli, who died this past November, the Berlinale will screen Il Marchese del Grillo, for which Monicelli won a Silver Bear in 1982. In 2011 the main venues of this programme are the Kino International and the Friedrichstadtpalast, where the Berlinale Special Gala Screenings will 61. Internationale Filmfestspiele be held. Berlin 10. – 20.02.2011 Berlinale Special - Gala Screenings in the Friedrichstadtpalast Press Office Potsdamer Straße 5 The King's Speech Great Britain / Australia 10785 Berlin by Tom Hooper (The Damned United) Phone +49 · 30 · 259 20 · 707 with Colin Firth, Geoffrey Rush, Helena Bonham Carter, Guy Pearce Fax +49 · 30 · 259 20 · 799 German premiere [email protected] www.berlinale.de Late Bloomers France by Julie Gavras (Blame it on Fidel) with Isabella Rossellini, William Hurt, Joanna Lumley, Simon Callow World premiere Sing Your Song USA (documentary) A film by Susanne Rostock about Harry Belafonte International premiere Ein Geschäftsbereich der Zhao Shi Gu Er (Sacrifice) People’s Republic of China Kulturveranstaltungen des by Chen Kaige (Mei Lanfang - Forever Enthralled, Wu Ji - The Promise) Bundes in Berlin (KBB) GmbH with Ge You, Wang Xue Qi, Fan Bing Bing, Huang Xiao Ming Management: International premiere Dieter Kosslick (Intendant Internationale Filmfestspiele Berlin), -

Award-Winning Hong Kong Film Gallants to Premiere at Hong Kong

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE Award-winning Hong Kong film Gallants to premiere at Hong Kong Film Festival 2011 in Singapore One-week festival to feature a total of 10 titles including four new and four iconic 1990s Hong Kong films of action and romance comedy genres Singapore, 30 June 2011 – Movie-goers can look forward to a retro spin at the upcoming Hong Kong Film Festival 2011 (HKFF 2011) to be held from 14 to 20 July 2011 at Cathay Cineleisure Orchard. A winner of multiple awards at the Hong Kong Film Awards 2011, Gallants, will premiere at HKFF 2011. The action comedy film will take the audience down the memory lane of classic kung fu movies. Other new Hong Kong films to premiere at the festival include action drama Rebellion, youthful romance Breakup Club and Give Love. They are joined by retrospective titles - Swordsman II, Once Upon A Time in China II, A Chinese Odyssey: Pandora’s Box and All’s Well, Ends Well. Adding variety to the lineup is Quattro Hong Kong I and II, comprising a total of eight short films by renowned Hong Kong and Asian filmmakers commissioned by Brand Hong Kong and produced by the Hong Kong International Film Festival Society. The retrospective titles were selected in a voting exercise that took place via Facebook and SMS in May. Public were asked to select from a list of iconic 1990s Hong Kong films that they would like to catch on the big screen again. The list was nominated by three invited panelists, namely Randy Ang, local filmmaker; Wayne Lim, film reviewer for UW magazine; and Kenneth Kong, film reviewer for Radio 100.3.