WIKIPEDIA | KATHY ACKER | Page 1

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Robert Morris, Minimalism, and the 1960S

City University of New York (CUNY) CUNY Academic Works All Dissertations, Theses, and Capstone Projects Dissertations, Theses, and Capstone Projects 1988 The Politics of Experience: Robert Morris, Minimalism, and the 1960s Maurice Berger Graduate Center, City University of New York How does access to this work benefit ou?y Let us know! More information about this work at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu/gc_etds/1646 Discover additional works at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu This work is made publicly available by the City University of New York (CUNY). Contact: [email protected] INFORMATION TO USERS The most advanced technology has been used to photograph and reproduce this manuscript from the microfilm master. UMI films the text directly from the original or copy submitted. Thus, some thesis and dissertation copies are in typewriter face, while others may be from any type of computer printer. The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. Broken or indistinct print, colored or poor quality illustrations and photographs, print bleedthrough, substandard margins, and improper alignment can adversely affect reproduction. In the unlikely event that the author did not send UMI a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if unauthorized copyright material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. Oversize materials (e.g., maps, drawings, charts) are reproduced by sectioning the original, beginning at the upper left-hand corner and continuing from left to right in equal sections with small overlaps. Each original is also photographed in one exposure and is included in reduced form at the back of the book. -

Phd Thesis the Anglo-American Reception of Georges Bataille

1 Eugene John Brennan PhD thesis The Anglo-American Reception of Georges Bataille: Readings in Theory and Popular Culture University of London Institute in Paris 2 I, Eugene John Brennan, hereby declare that this thesis and the work presented in it is entirely my own. Where information has been derived from other sources, I confirm that this has been indicated in the thesis. Signed: Eugene Brennan Date: 3 Acknowledgements This thesis was written with the support of the University of London Institute in Paris (ULIP). Thanks to Dr. Anna-Louis Milne and Professor Andrew Hussey for their supervision at different stages of the project. A special thanks to ULIP Librarian Erica Burnham, as well as Claire Miller and the ULIP administrative staff. Thanks to my postgraduate colleagues Russell Williams, Katie Tidmash and Alastair Hemmens for their support and comradery, as well as my colleagues at Université Paris 13. I would also like to thank Karl Whitney. This thesis was written with the invaluable encouragement and support of my family. Thanks to my parents, Eugene and Bernadette Brennan, as well as Aoife and Tony. 4 Thesis abstract The work of Georges Bataille is marked by extreme paradoxes, resistance to systemization, and conscious subversion of authorship. The inherent contradictions and interdisciplinary scope of his work have given rise to many different versions of ‘Bataille’. However one common feature to the many different readings is his status as a marginal figure, whose work is used to challenge existing intellectual orthodoxies. This thesis thus examines the reception of Bataille in the Anglophone world by focusing on how the marginality of his work has been interpreted within a number of key intellectual scenes. -

'Understand' Transgressive Fiction

Word and Text Vol. IV, Issue 1 26 – 39 A Journal of Literary Studies and Linguistics June / 2014 The Lacuna of Usefulness: The Compulsion to ‘Understand’ Transgressive Fiction Molly Hoey James Cook University, Townsville E-mail: [email protected] Abstract This article takes a brief look at why Transgressive Fiction from the 1990s has been under represented in academic circles and then examines why it was so often misread by reviewers and critics from this period. Transgressive Fiction intentionally frustrates readers using traditional referential modes of criticism by refusing to provide an objective meaning, ideology or structure. This refusal forces the reader to either engage in the text personally or begin a process of rejection and assimilation. This practice can be avoided if Transgressive texts are considered via subjective affectivism (the reader’s reaction and involvement) rather than by the quality of their execution and subject matter. This opens the way for the text to function as a place for consequence-free exploration and the enactment of taboos and their transgression. Keywords: Barthes, Bataille, Transgressive Fiction, value, subjective affectivism The term “Transgressive Fiction” was popularized in 1993 by LA Times columnist Michael Silverblatt1 and has since been used to describe a range of texts which expound the Sadean paralogy of violence, mutilation, cruelty and deviance for the pleasure of the sovereign individual, where the desires of the depersonalizing subject can be projected onto the passive object. This is evidenced in Will Self’s Cock and Bull when Carol assaults her husband with her newly emerged penis: He barely noticed when she turned him over. -

On Teaching Transgressive Literature

The CEA Forum Summer/Fall 2008: 37.2 Next: Thinking Ecology ON TEACHING TRANSGRESSIVE LITERATURE Layne Neeper The carnivalization of American culture has become ubiquitous as we advance into the 21st century. Shock television from Spike TV to The Jerry Springer Show to Cheaters crowds morning and late-night programming. Unspeakable options catering to every possible desire are provided by the Internet. Fetishized violence, often sexual violence like that found in the Saw franchise, Turista, Seven, and The Watcher, remains a Hollywood staple. Eminem rapped about disemboweling his former wife and record sales boomed. But what happens when the transgressive text is introduced into the more intimate space of the college classroom, when the outrageous �outside� is brought �inside?� More specifically still, what processes and responses typically arise as transgressive novels appear on more and more of our syllabi? Instructors who choose to include Kathy Acker's Blood and Guts in High School, Dennis Cooper's Try, or even those old war horses of the contemporary seminar Lolita or Naked Lunch, often find that when such works are to be taught and discussed in frank and serious-minded ways, there is, on the one hand, typically a surprising resistance, even outrage, on the part of many students who, outside the classroom, are otherwise ardent consumers�as are we all�of whatever the popular culture disgorges for our leisure. Perhaps not unsurprisingly, the �moral laxity� said to afflict our students often hardens into something less tolerant, less pliant, when they confront the written word in the public sphere of the classroom. -

Reading the Novels of Kathy Acker As Simulacra Jennifer Komorowski

49 A Space to Write Woman-Becoming: Reading the Novels of Kathy Acker as Simulacra Jennifer Komorowski The novels of American experimental Guts in High School (1978), I argue that we can un- novelist Kathy Acker make strategic use of pla- derstand the way in which she simultaneously ex- giaristic techniques that function as simulacra, poses how the simulacrum functions while also which serve to undermine the original Platonic making use of the simulacrum to subvert phal- Ideas upon which they are based and in doing locentric language by “appropriating male texts ... so create a new aesthetic existence. In Gilles and trying to fnd [her] voice as a woman” (Fried- Deleuze’s Difference and Repetition (1968), he ex- man 13). Acker admits in an interview with El- amines the role of the simulacra in overturning len G. Friedman that act of rewriting Don Quixote Platonism by denying the primacy of “original (1605) by Miguel de Cervantes was an attempt over copy, of model over image” (66). Deleuze’s to copy out the text with the explicit idea of see- concept is central to interpreting the work of ing “what pure plagiarism would look like” (13).1 Acker as a piece of literature that subverts phal- Instead of the result being a copy of the original locentric writing traditions in order to overcome novel, however, Acker’s Don Quixote “breaks up patriarchal hangovers. I begin by providing an ex- the homogeneity of culture, exposing the numer- planation of this paper’s theoretical groundwork, ous and varied discourses that at any moment which is based on several of Deleuze’s writings infuence and shape each of us” (Pitchford 59). -

The Dialectics of Class and Postcolonialism in Cities of the Red Night

WILLIAM FREDERICK II The Dialectics of Class and Postcolonialism in Cities of the Red Night Authors by nature of their writing activities enter into a dialogue with the society that surrounds them, as well as their readers. For postcolonial writers this dialogue also includes the society of the coloniser. Yet, writing is a function of class as well; textual artefacts are inextricably tied to economic conditions past, present and future. All of these elements flicker in and out of focus in the myriad texts that facilitate the legacy of a culture. Texts are microcosms of their attendant culture(s). The academic John McLeod offers some perspective on colonialism’s ongoing influence, saying that “colonialism’s historical and cultural consequences remain very much a part of the present” (p4; TRCtPS). Withdrawal of the coloniser (or imperialist) does not remove, or even perhaps diminish, the socio- cultural effects of colonisation. One way this is reflected is in the colonised culture’s texts. Socio-cultural behaviours as well as the coloniser’s worldview remain in the colonised culture, influencing many streams of discourse flowing through the indigenous culture; domination and influence do not cease being issues when physical presence ends. Postcolonial discourse consists of attempts at “resisting, challenging and even transforming prejudicial forms of knowledge in the past and present” (p5; TRCtPS). The American author William S. Burroughs takes part in such discourse while simultaneously engaging with readers who are not generally perceived as being part of his ostensible audience. In the first two decades of his writing, William S. Burroughs primarily addressed an ‘outsider’ or marginalist audience. -

Diplomová Práce Studijní Program: Anglická Filologie Vedoucí Práce: Mgr

UNIVERZITA PALACKÉHO V OLOMOUCI Filozofická fakulta ‘I AM JACK’S BROKEN HEART’- TRANSGRESSIVE SEX AS A REFLECTION OF CHARACTERS’ PERSONALITY IN CHUCK PALAHNIUK’S SURVIVOR, LULLABY, CHOKE AND FIGHT CLUB Magisterská diplomová práce Studijní program: Anglická filologie Vedoucí práce: Mgr. Vladimíra Fonfárová, Ph.D. Autor: Bc. Marika Nováková Olomouc 2016 Prohlašuji, že jsem diplomovou práci na téma: ‘I am Jack’s broken heart’- Transgressive Sex as a Reflection of Characters’ Personality in Chuck Palahniuk’s Survivor, Lullaby , Choke and Fight Club vypracovala samostatně pod odborným dohledem vedoucí práce a uvedla jsem všechny použité podklady a literaturu. V …………..… dne…………… Podpis…………………………………. ACKNOWLEDGMENTS “Nothing of me is original. I am the combined effort of everybody I’ve ever known.” - Chuck Palahniuk, Invisible Monsters Děkuji vedoucí své diplomové práce, Mgr. Vladimíře Fonfárové, Ph.D., jež byla ochotná mi externě odvést práci, vždy mi dát cenné rady a pomoct mi překonat strasti akademického psaní. Bez její pomoci, trpělivosti a laskavosti by tato práce nevznikla. Děkuji vyučujícím na katedře anglistiky a amerikanistiky za jejich čas a energii vložené do našeho vzdělání, jehož plody jsem se snažila uplatnit ve své práci. Děkuji rovněž svým přátelům, především Markétě Fořtové, Vendule Hřivnové a Kláře Jaluvkové, které mi vždy poskytnuly útěchu a pomoc v průběhu studia a jejich přátelství mi bylo oporou v neveselých časech. Děkuji rovněž své rodině, hlavně mojí mamince, bez které bych nebyla tam, kde jsem. Její obětavost pro mé vzdělání byla výjimečná. Její podpora nepostradatelná a její láska nekonečná. A v neposlední řadě děkuji Chucku Palahniukovi. Každý jeho román mi otevírá obzory a ukazuje nové možnosti. -

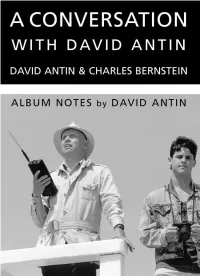

A Conversation with David Antin

A CONVERSATION WITH DAVID ANTIN DAVID ANTIN & CHARLES BERNSTEIN ALBUM NOTES by DAVID ANTIN GRANARY BOOKS NEW YORK CITY 2002 © 2002 David Antin, Charles Bernstein & Granary Books, Inc. All rights reserved. No portion of this book may be reproduced without express written permission of the author or publisher. A portion of this conversation was published in The Review of Contemporary Fiction, Vol. XXI No. 1, Spring 2001. Printed and bound in the United States of America in an edition of 1000 copies of which 26 are lettered and signed. Cover and Book Design: Julie Harrison Cover photo: Phel Steinmetz Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Antin, David. A conversation with David Antin / David Antin and Charles Bernstein ; and album notes, David Antin. p. cm. ISBN 1-887123-55-5 1. Antin, David--Interviews. 2. Poets, American--20th century--Interviews. I. Bernstein, Charles, 1950- II. Title. PS3551.N75 Z465 2002 811'.54--dc21 2002001192 Granary Books, Inc. 307 Seventh Ave. Suite 1401 New York, NY 10001 USA www.granarybooks.com Distributed to the trade by D.A.P./Distributed Art Publishers 155 Avenue of the Americas, Second Floor New York, NY 10013-1507 Orders: (800) 338-BOOK • Tel.: (212) 627-1999 • Fax: (212) 627-9484 Also available from Small Press Distribution 1341 Seventh Street Berkeley, CA 94710 Orders: (800) 869-7553 • Tel.: (510) 524-1668 • Fax: (510) 524-0582 www.spdbooks.org David Antin and Charles Bernstein Charles Bernstein: In 1999, I had the opportunity to tour Brooklyn Technical High School with my daughter Emma, who was just going into ninth grade. -

Interrelation Between the Author and the Text in W. S. Burroughs's Naked Lunch and Chuck Palahniuk's Fight Club

Питання літературознавства / Pytannia literaturoznavstva / Problems of Literary Criticism /№ 89/ /2014/ УДК 82.09 INTERRELATION BETWEEN THE AUTHOR AND THE TEXT IN W. S. BURROUGHS’S NAKED LUNCH AND CHUCK PALAHNIUK’S FIGHT CLUB Вікторія Сергіївна Грівіна [email protected] Аспірантка Кафедра історії зарубіжної літератури і класичної філології Харківський національний університет імені В. Н. Каразіна Пл. Свободи, 4, 61022, м. Харків, Україна Анотація. Досліджується еволюція письменницької ідентичності в „Голому сніданку” У. Берроуза і „Бійцівському клубі” Ч. Паланіка в контексті Лаканівського концепту стадії дзеркала. Формування письменника порівнюється з формуванням особистості в практиці психоаналізу. Дослідження має на меті з’ясувати, зокрема, особливості автора трансгресивного тексту. Текст даного характеру здатен розкривати та проявляти як соціальні, так і особистісні табу. В процесі експлікації табу або замовчення цей текст скандалізує читача, викликає гострі негативні реакції описом відвертої еротики та жорстокості, наявністю чорного гумору тощо. Дослідження етапів становлення трансгресивного автора допоможе в подальшому зрозуміти соціальне значення необхідності експлікації табу в літературі. Ключові слова: трансгресивна література, ліміт, стадія дзеркала, фрагментоване тіло. Chuck Palahniuk has been compared to William Burroughs by researchers ranging from M. Bolton to J. Dolph and most recently K. Hume [5]. However the two have never been placed next to each other on the most obvious and therefore the closest ground, the ground of transgressive aesthetics. “The text so sharp it is painful both to write and to read”, Burroughs’s friend Brion Gysin once described Naked Lunch [4]. As for Palahniuk the author of Fight Club admitted in an interview given to Lightspeed Magazine that what he writes can be most accurately described as transgressive fiction in a sense that he sometimes counts “how many people would faint on his readings” [13, p. -

David Antin: Listening and Listing Hélène Aji

David Antin: listening and listing Hélène Aji To cite this version: Hélène Aji. David Antin: listening and listing. Golden Handcuffs Review, Lou Rowan, 2018, 2 (24), pp.22-47. hal-02000279 HAL Id: hal-02000279 https://hal.parisnanterre.fr//hal-02000279 Submitted on 6 Feb 2019 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. David Antin: listening and listing1 Hélène Aji or maybe i should go in with a video camera instead of a view1 camera and ask these people if they want to tell me what they think its like their life and i shoot it and show it to them so they can give me their second thoughts about it because maybe they think their first thoughts werent right it seems to me most people would want to take a crack at that making their own self-portrait especially if they arent worried about their lack of readiness or competence and have a chance for second thoughts except perhaps in that part of the art world where no one has second thoughts about his life because you cant have second thoughts where there are no first ones (Antin “remembering recording representing” in Dawsey 190) 1 The final version of this article owes a lot to the editing suggestions made by three students in my poetry seminar at the University of Texas at Austin (Fall 2017): Hailey Kriska, John Calvin Pierce, and Emma Whitworth were supportive and constructive as I struggled with the distressing fact of writing about David’s work without David. -

Kathy Acker and Transnationalism

Kathy Acker and Transnationalism Kathy Acker and Transnationalism Edited by Polina Mackay and Kathryn Nicol Kathy Acker and Transnationalism, Edited by Polina Mackay and Kathryn Nicol This book first published 2009 Cambridge Scholars Publishing 12 Back Chapman Street, Newcastle upon Tyne, NE6 2XX, UK British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library Copyright © 2009 by Polina Mackay and Kathryn Nicol and contributors All rights for this book reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior permission of the copyright owner. ISBN (10): 1-4438-0570-X, ISBN (13): 978-1-4438-0570-4 To Kathy Acker, that wandering mind who left us more dazed than before. Kathy Acker with Ellen G. Friedman on Acker’s 41st birthday. Courtesy of Friedman. TABLE OF CONTENTS List of Illustrations ..................................................................................... ix Foreword .................................................................................................... xi Kathy Acker: Wandering Jew Ellen G. Friedman Acknowledgements .................................................................................. xxi Introduction ................................................................................................. 1 The Postmodern, Transnationalism, and Global Identity Polina Mackay and Kathryn Nicol Abbreviations -

The Uses of Photography: Art, Politics, and the Reinvention of a Medium

DECEMBER 2016–MARCH 2017 EXHIBITIONS LA JOLLA THE USES OF PHOTOGRAPHY: ART, POLITICS, AND THE REINVENTION OF A MEDIUM ON VIEW THROUGH 1/2/2017 The Uses of Photography: Art, Politics, and the Reinvention of a Medium examines a constellation of artists who were active in San Diego between the late 1960s and mid-1980s and whose experiments with photography opened the medium to a profusion of new strategies and subjects. These artists introduced urgent social issues and themes of everyday life into the seemingly neutral territory of conceptual art, through photographic works that took on hybrid forms, from books and postcards to video and text-and-image installations. Tracing a crucial history of photoconceptual practice, The Uses of Photography focuses on the extraordinary artistic community that formed in and around the University of California, San Diego. These artists employed photography and its expanded forms as a means to dismantle modernist autonomy, to contest notions of photographic truth, and to engage in political critique. The work of these artists shaped emergent accounts of postmodernism in the visual arts and their influence is felt throughout the global contemporary art world today. This critically-acclaimed exhibition features approximately 100 works, many of them rarely seen, THE USES OF PHOTOGRAPHY: POLITICS, ART, AND THE and presents Carrie Mae Weems’s S.E. San Diego series (1982-83) in its entirety for the first time since its creation. The Uses of Photography is accompanied by a richly illustrated catalogue co-published by MCASD and University of California Press, with contributions by David Antin, Jill Dawsey, Pamela M.