A Curated Online Educational Portal for Staff and Students at a University of Technology

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Online Research Tools

Online Research Tools A White Paper Alphabetical URL DataSet Link Compilation By Marcus P. Zillman, M.S., A.M.H.A. Executive Director – Virtual Private Library [email protected] Online Research Tools is a white paper link compilation of various online tools that will aid your research and searching of the Internet. These tools come in all types and descriptions and many are web applications without the need to download software to your computer. This white paper link compilation is constantly updated and is available online in the Research Tools section of the Virtual Private Library’s Subject Tracer™ Information Blog: http://www.ResearchResources.info/ If you know of other online research tools both free and fee based feel free to contact me so I may place them in this ongoing work as the goal is to make research and searching more efficient and productive both for the professional as well as the lay person. Figure 1: Research Resources – Online Research Tools 1 Online Research Tools – A White Paper Alpabetical URL DataSet Link Compilation [Updated: August 26, 2013] http://www.OnlineResearchTools.info/ [email protected] eVoice: 800-858-1462 © 2005, 2006, 2007, 2008, 2009, 2010, 2011, 2012, 2013 Marcus P. Zillman, M.S., A.M.H.A. Online Research Tools: 12VPN - Unblock Websites and Improve Privacy http://12vpn.com/ 123Do – Simple Task Queues To Help Your Work Flow http://iqdo.com/ 15Five - Know the Pulse of Your Company http://www.15five.com/ 1000 Genomes - A Deep Catalog of Human Genetic Variation http://www.1000genomes.org/ -

Hofstra University Film Library Holdings

Hofstra University Film Library Holdings TITLE PUBLICATION INFORMATION NUMBER DATE LANG 1-800-INDIA Mitra Films and Thirteen/WNET New York producer, Anna Cater director, Safina Uberoi. VD-1181 c2006. eng 1 giant leap Palm Pictures. VD-825 2001 und 1 on 1 V-5489 c2002. eng 3 films by Louis Malle Nouvelles Editions de Films written and directed by Louis Malle. VD-1340 2006 fre produced by Argosy Pictures Corporation, a Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer picture [presented by] 3 godfathers John Ford and Merian C. Cooper produced by John Ford and Merian C. Cooper screenplay VD-1348 [2006] eng by Laurence Stallings and Frank S. Nugent directed by John Ford. Lions Gate Films, Inc. producer, Robert Altman writer, Robert Altman director, Robert 3 women VD-1333 [2004] eng Altman. Filmocom Productions with participation of the Russian Federation Ministry of Culture and financial support of the Hubert Balls Fund of the International Filmfestival Rotterdam 4 VD-1704 2006 rus produced by Yelena Yatsura concept and story by Vladimir Sorokin, Ilya Khrzhanovsky screenplay by Vladimir Sorokin directed by Ilya Khrzhanovsky. a film by Kartemquin Educational Films CPB producer/director, Maria Finitzo co- 5 girls V-5767 2001 eng producer/editor, David E. Simpson. / una produzione Cineriz ideato e dirètto da Federico Fellini prodotto da Angelo Rizzoli 8 1/2 soggètto, Federico Fellini, Ennio Flaiano scenegiatura, Federico Fellini, Tullio Pinelli, Ennio V-554 c1987. ita Flaiano, Brunello Rondi. / una produzione Cineriz ideato e dirètto da Federico Fellini prodotto da Angelo Rizzoli 8 1/2 soggètto, Federico Fellini, Ennio Flaiano scenegiatura, Federico Fellini, Tullio Pinelli, Ennio V-554 c1987. -

Inside Arts - Corpses As Art!

The student ‘news’paper of Imperial College London The Non-Epic Fail Edition Issue 1,416 Friday 21 November 2008 felixonline.co.uk felix Inside Arts - Corpses as art! Page 15 Music - Nickelback review Page 24 Feature - Brighton Run Page 31 Sport - Build up to Varsity Trouble in begins Hammersmith...Imperial College Football Club in trouble after pub crawl in Hammersmith, but are there signs of change? See pages 4 & 5 Page 37 2 felix Friday 21 November 2008 Friday 21 November 2008 felix 3 News [email protected] News News Editor – Kadhim Shubber [email protected] Imperial Bioscientist New stealth tax New postgraduate and Conservatives see 50% target as unrealistic students win gold in increases cost of international positions to Dina Ismali versity participation rate for young News Correspondent people has only risen by 0.6% since worldwide competition living for students 1999-2000 and stands at 39.8%. The government’s approach to univer- The Organisation for Economic Co- Daniel Wan in the project.) industrial procedures, from recon- Kadhim Shubber ernment, said: be created in Council sity expansion is like “trying to drive a operation and Development’s (OECD) News Correspondent Professor Richard Kitney, a Professor structive surgery to the manufacture Deputy Editor “This is a second hit on students, just car with the accelerator and brake both annual evaluation of different educa- of the Imperial team gauged the inter- of eco-clothing. Professor Paul Free- days after the Government’s decision Jovan Nedić pressed to the floor”, says Tory univer- tion systems shows that the UK has An Imperial College team of nine un- national achievement they attained, mont, another of the team’s advis- New laws introduced by the govern- to cut student grants. -

Smart Content Providers

Smart Content Providers Video Audio Photos Products/Other #REKT Acast 23hq 23degrees ABC News Adori Labs Accredible 360 Panorama Adventr Allears Achewood 360 Stories Adways Anchor FM Altizure 3DCrafts Alkışlarla Yaşıyorum ART19 deviantART Abstract All Things Digital AudioBoom Dinosaur Comics Acebot.ai Altru Audiomack Dribbble Airtable Alugha Audm Droplr Allego Aniboom Ausha EyeEm Allihoopa Animoto Backtracks Flickr Alpaca Maps Athenascope Bandcamp gfycat Alpha Hat Bambuser BingeWith GifVif Apester Brightcove BlogAudio Giphy AppFollow Buto.tv Blogcast Img.ly Apple Keynote CANAL+ Bubbli Imgur ArcGIS StoryMaps Cayke Buzzsprout instagram Archilogic CBS News Cadence 13 Kuula ARCHIVOS Cinema8 Canva meadd Are.na Cinnamon Changelog Mobypicture AskMen Cincopa Chirbit Momento360 Autodesk Screencast Clip Syndicate Clyp Ow.ly Avocode Clipfish DNBRadio PanoMoments Bad Panda Clippit Flat Pexels Badgr CloudApp Free Music Archive photozou BadJupiter CNBC Genius pikchur Beautiful AI CNN Grooveshark Pollstar Behance CNN Edition Himalaya Publitio Bitmark CNN Money Huffduffer Questionable Content Blogsend.io College Humor iHeartRadio Represent BlueprintUE Confreaks Infinity.fm SmugMug Bootkik Coub Instaread Someecards Boston.com Crackle Last.fm The Hype Machine Box Office Buz Daily Motion Liberated Syndication Tinypic Brainshark Discovery Channel Listle tochka.net Brainsonic dotSUB Listen Notes TwitrPix BranchTrack Dream Broker Megafono uludağ sözlük galeri Bravo Tv DTube Megaphone.fm Vidme buk.io Embedded Mymixtapez Minilogs xkcd Buncee embedly Mixcloud Zoomable -

Invisible Soldier Iraq Vets Are Landing on the Streets

THE INDY WINS BIG AT THE IPA PRESS AWARDS! SEE P3 THEINDYPENDENT Issue #62, December 22, 2004 – Januray 11, 2005 • a free paper for free people Invisible Soldier Iraq vets are landing on the streets. More are on the way. SEE PAGE 4 ; ©ANDREW STERN/ANDREWSTERN.NET ANTRIM CASKEY UGANDA PEACE ON ONE SMALL CORNER PATRIOT ACT II OF EARTH BIG PAGE 8 BROTHER JUST GOT THE ONLY BIGGER MUSICIAN PAGE 5 THAT MATTERED indypendent.org PAGE 10 PREACHING THE GOSPEL OF REVOLUTION BY KIERA BUTLER On the third Sunday of NEW YORK CITY advent, the Reverend Earl INDEPENDENT Kooperkamp told his The gregarious Reverend Kooperkamp remains animated after the 10a.m. service, as he MEDIA CENTER congregation at St. Mary’s runs off to a vestry meeting. Below Left: Reverend Kooperkamp succors a parishioner, Episcopal Church to go. and they’re both left laughing. PHOTOS: ANTRIM CASKEY Phone: 212.684.8112 “Go. Scram. Get outta here,” he said, flick- When Reverend Kooperkamp became pas- come out when he pronounces the name of Email: ing his hand at the 30 or so congregants in tor of St. Mary’s Church four and a half years the city where he grew up. “Low-ville,” he [email protected] the pews. ago, he knew he wanted to continue the tra- says for Louisville, Kentucky. He remembers Actually, he was (very loosely) quoting dition of community activism. going to church with his family during the Web: Jesus Christ. Christ, Kooperkamp explained, Shortly after the terrorist attacks of Vietnam War; it was during that time that he NYC: www.nyc.indymedia.org was always telling people to “go.” To go September 11, 2001, Kooperkamp hosted the realized that he wanted to be a pastor and GLOBAL: www.indymedia.org spread his teachings. -

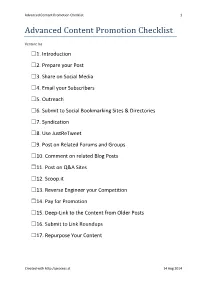

Advanced Content Promotion Checklist 1

Advanced Content Promotion Checklist 1 Advanced Content Promotion Checklist Venture Inc ☐ 1. Introduction ☐ 2. Prepare your Post ☐ 3. Share on Social Media ☐ 4. Email your Subscribers ☐ 5. Outreach ☐ 6. Submit to Social Bookmarking Sites & Directories ☐ 7. Syndication ☐ 8. Use JustReTweet ☐ 9. Post on Related Forums and Groups ☐ 10. Comment on related Blog Posts ☐ 11. Post on Q&A Sites ☐ 12. Scoop.it ☐ 13. Reverse Engineer your Competition ☐ 14. Pay for Promotion ☐ 15. Deep-Link to the Content from Older Posts ☐ 16. Submit to Link Roundups ☐ 17. Repurpose Your Content Created with http://process.st 14 Aug 2014 Advanced Content Promotion Checklist 2 ☐ 1. Introduction Content marketing is not easy, it takes a lot of elbow grease to create valuable content and even more to promote it! The promotion part is something that many companies tend to miss when looking at a content marketing strategy. A general rule of thumb is you should spend 30% of your time creating content and 70% promoting it. That’s why I created this checklist you can use to promote the content you work so hard to create. I’m writing this checklist for two purposes. Firstly, because I am interested in content promotion for my own company Process Street. Content marketing is something I’ve been experimenting with and seeing some great results with so far, writing this post is forcing me to research and learn more about content distribution. Secondly, because I want to make a template for this in Process Street so I can begin hand it off to my team. I am working towards a streamlined content marketing machine. -

Web 2.0 and Social Media for Business

Web 2.0 and Social Media for Business Roger McHaney Download free books at Roger W. McHaney Web 2.0 and Social Media for Business Download free eBooks at bookboon.com 2 Web 2.0 and Social Media for Business 2nd edition © 2013 Roger W. McHaney & bookboon.com ISBN 978-87-403-0514-2 Download free eBooks at bookboon.com 3 Web 2.0 and Social Media for Business Contents Contents 1 Introduction to Web 2.0 8 1.1 The Internet and World Wide Web 8 1.2 Web 2.0 Defined 10 1.3 Conclusions 31 1.4 Bibliography 31 2 Blogging for Business 34 2.1 Voice and Personality 36 2.2 Blog Environments 42 2.3 Building a Blog 48 2.4 Conclusions 68 2.5 Bibliography 68 3 More Blogging: WordPress Options 70 3.1 Customizing a WordPress Blog 70 3.2 General Settings 81 - ste the of th + - c + in ++ ity Be a part of the equation. RMB Graduate Programme applications are now open. Visit www.rmb.co.za to submit your CV before the 23rd of August 2013. Download free eBooks at bookboon.com 4 Click on the ad to read more Web 2.0 and Social Media for Business Contents 3.3 Using Widgets 83 3.4 Blog Posts 86 3.5 Adding Mobile and iPad Options 90 3.6 Managing Pages 92 3.7 Connecting with Search Engines 94 3.8 Connecting with Customers 98 3.9 Conclusions 103 3.10 Bibliography 103 4 Beyond Blogging: RSS and Podcasting 104 4.1 RSS Defined 104 4.2 RSS in Practice 109 4.3 Podcasting 118 4.4 Conclusions 134 4.5 Bibliography 135 5 Videocasting, Screencasting and Live Streaming 136 5.1 Videocasting 136 5.2 Screencasting 153 5.3 Live Streaming 156 The next step for top-performing graduates Masters in Management Designed for high-achieving graduates across all disciplines, London Business School’s Masters in Management provides specific and tangible foundations for a successful career in business. -

Learn Languages, Explore Cultures, Transform Lives Moeller, Editor

2015 Learn Languages, Explore Cultures, Learn Languages, Explore Cultures, Transform Lives Learn Transform Languages, Cultures, Explore Transform Lives Editor Aleidine J. Moeller University of Nebraska–Lincoln Articles by: Sharon Wilkinson Patricia Calkins Tracy Dinesen Theresa R. Bell Diane Ceo-Francesco J. S. Orozco-Domoe Rebecca L. Chism Leah McKeeman Blanca Oviedo Katya Koubek John C. Bedward Heidy Cuervo Carruthers Jason R. Jolley Lucianne Maimone Colleen Neary-Sundquist Clara Burgo Moeller, Editor Moeller, Elizabeth Harsma 2015 Report of the Central States Conference on the Teaching of Foreign Languages Learn Languages, Explore Cultures, Transform Lives Selected Papers from the 2015 Central States Conference on the Teaching of Foreign Languages Aleidine J. Moeller, Editor University of Nebraska–Lincoln 2015 Report of the Central States Conference on the Teaching of Foreign Languages iv Learn Languages, Explore Cultures, Transform Lives Publisher: Robert M. Terry 2211 Dickens Road, Suite 300 Richmond, VA 23230 Printer: Johnson Litho Graphics of Eau Claire, Ltd. 2219 Galloway Street Eau Claire, WI 54703 © 2015 Central States Conference on the Teaching of Foreign Languages Patrick T. Raven, Executive Director 7141A Ida Red Road Egg Harbor, WI 54209-9566 Phone: 414-405-4645 FAX: 920-868-1682 [email protected] www.csctfl.org C P 0 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1 v Review and Acceptance Procedures Central States Conference Report The Central States Conference on the Teaching of Foreign LanguagesReport is a refereed volume of selected papers based on the theme and program of the Central States Conference on the Teaching of Foreign Languages. Abstracts for sessions are first submitted to the Program Chair, who then selects sessions that will be presented at the annual conference. -

The Presentation Guild 2018 Annual Salary Survey Report

THE PRESENTATION GUILD 2018 ANNUAL SALARY SURVEY REPORT June 2018 CONTENTS Introduction 3 Our Presentationist Profile 4 Key Conclusions 5 Survey Results 6 Correlations 29 Objectives Based on Survey Results 34 Introduction Founded as an advocate for you, the presentation professional, the Presentation Guild is committed to supporting our industry. In our effort to give you a stronger voice and to establish benchmarks, last year we conducted the first-ever presentation professional salary survey. In late 2017, the Presentation Guild conducted the second annual salary survey. The survey consisted of 24 questions designed to reveal the compensation characteristics of the average presentation professional—or presentationist, as we like to say. This time we expanded our reach to include presentationists from around the globe. We received 204 responses, nearly double the number of responses in the benchmark survey. A big shout-out goes to those Guild members who volunteered countless hours to create and conduct the survey, aggregate the data, generate insights and write and design the report. Thanks also to those who completed the survey, contributing robust data that is the foundation of this report. We are grateful for your support of the presentation industry. Onward and upward! The Presentation Guild Salary Survey Committee The Presentation Guild 2018 Annual Salary Survey Report I © 2018 Presentation Guild 3 What is a Presentationist, Anyway? Wait a minute. Presentationist? Where in the world are these companies? Tell me about the demographics of What is a presentationist, anyway? presentationists. Who are they? Most of us work in the UK, Canada, and the US, It’s us—people who create, support, and deliver with most of the US members located in California The majority of us are female, between the ages presentations in a professional capacity—204 of and New York. -

Design and Implementation of Multi-Head Presentation Software for the Ios Platform Michael S

Southern Adventist University KnowledgeExchange@Southern MS in Computer Science Project Reports School of Computing Winter 2-24-2015 Design and Implementation of Multi-head Presentation Software for the iOS Platform Michael S. Babienco Southern Adventist University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://knowledge.e.southern.edu/mscs_reports Part of the Computer Sciences Commons Recommended Citation Babienco, Michael S., "Design and Implementation of Multi-head Presentation Software for the iOS Platform" (2015). MS in Computer Science Project Reports. 1. https://knowledge.e.southern.edu/mscs_reports/1 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the School of Computing at KnowledgeExchange@Southern. It has been accepted for inclusion in MS in Computer Science Project Reports by an authorized administrator of KnowledgeExchange@Southern. For more information, please contact [email protected]. DESIGN AND IMPLEMENTATION OF MULTI-HEAD PRESENTATION SOFTWARE FOR THE iOS PLATFORM by Michael S. Babienco A PROJECT DEFENSE Presented to the Faculty of The School of Computing at Southern Adventist University In Partial Fulfilment of Requirements For the Degree of Master of Science Major: Computer Science Under the Supervision of Professor Hall Collegedale, Tennessee February, 2015 DESIGN AND IMPLEMENTATION OF MULTI-HEAD PRESENTATION SOFTWARE FOR THE iOS PLATFORM Michael S. Babienco Southern Adventist University, 2015 Adviser: Tyson Hall, Ph.D. ShareSynch, currently available for both Windows and Mac OS X, is a presen- tation software application tailored towards evangelistic speakers with limited experience. The software has several essential features including the use of speaker notes during a presentation, support for independent slide and speaker note lan- guage, speaker note pagination with dynamic font scaling, editing of presentations and rich text speaker notes from within the application, and dynamic appeal video configuration. -

Roger Courville the Virtual Presenter’S Playbook by Roger Courville © 2015

THE VIRTUAL PRESENTER’S PLAYBOOK 250+ ideas for rocking your next webinar, webcast, or virtual class Roger Courville The Virtual Presenter’s Playbook by Roger Courville © 2015 All rights reserved. Use of any part of this publication, whether reproduced, transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photo- copying, recording, or otherwise, or stored in a retrieval system, without the prior consent of the publisher, is an infringement of copyright law and is forbidden. Print ISBN: 978-0-9965201-0-2 eBook ISBN: 978-0-9965201-1-9 Lead Editor: Jennifer Regner Cover and Interior Design by: Fusion Creative Works, fusioncw.com For more information, contact: Roger Courville at +1.503.329.1662, [email protected], @rogercourville, or via carrier pigeon. Interested in bulk purchases or distributing the eBook en masse? Give a ring. Published by: 1080 Group, LLC 24111 NE Halsey Street, Suite 200 Troutdale, Oregon, 97060 USA +1.503.329.1662 First Printing Printed in the United States of America TheVirtualPresenter.com DEDICATION Scott Driscoll For faith—without which I’d not have a chance to do what I’m called to do. Vince Epperly For your gift of lifelong friendship manifest. Mark Corcoran, Sovann Pen, John Willsea, Justin Foster, Michael Santarcangelo For being my board. Tamar, Maia, and Alden Courville For being the reason to stay focused on love. CONTENTS Foreword 13 Introduction 15 ∙ Get the Most from This Book 18 Chapter 1: Thinking Strategically 21 ∙ Eight ways web conferencing creates value beyond saving 21 travel expenses -

Online Research Tools

Online Research Tools A White Paper Link Compilation By Marcus P. Zillman, M.S., A.M.H.A. Executive Director – Virtual Private Library [email protected] Online Research Tools is a white paper link compilation of various online tools that will aid your research and searching of the Internet. These tools come in all types and descriptions and many are web applications without the need to download software to your computer. This white paper link compilation is constantly updated and is available online in the Research Tools section of the Virtual Private Library’s Subject Tracer™ Information Blog: http://www.ResearchResources.info/ If you know of other online research tools both free and fee based feel free to contact me so I may place them in this ongoing work as the goal is to make research and searching more efficient and productive both for the professional as well as the lay person. Figure 1: Research Resources 1 Online Research Tools – A White Paper Link Compilation [Updated: February 2, 2010] http://www.OnlineResearchTools.info/ [email protected] eVoice: 800-858-1462 © 2005, 2006, 2007, 2008, 2009, 2010 Marcus P. Zillman, M.S., A.M.H.A. Research Tools 1Cast - Your Digital News Stand http://www.1cast.com/ 12seconds.tv - Video Status Updates http://www.12seconds.tv/ 191 Resources On Online Tools, Generators, Checkers http://www.listible.com/list/online-tools2C-generators2C-checkers 2008 Year-End Google Zeitgeist http://www.google.com/intl/en/press/zeitgeist2008/ 2collab - Research Collaboration Tool http://www.2collab.com/