Note 142: Le Mans Fastest Laps, 1932

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Ferrari Club Del Ducato E Emilia-Romagnaemilia-Roma Gna

Incontro con le scuderie Ferrari Club del Ducato e Emilia-RomaEmilia-Romagnagna Informazioni e Iscrizioni CPAE CLUB PIACENTINO AUTOMOTOVEICOLI D’EPOCA Via Bressani, 8 29017 Fiorenzuola d’Arda (PC) 0523 248930 377 1695441 [email protected] - www.cpae.it HAL C LE A N V G O E R P C . .P.A.E Bobbio, 28 AGOSTO 2016 L ¡¢£¤¥¦§¨§¢ ©¥ ¤ ¥ ¥ § ¦ ©¥ ¤¥ § ©§¨§ ¦§ ¥ ¢ ¦ tuale ACI Piacenza) e del Podestà di Bobbio e vide il successo del Duca Lui- Programma raduno Ferrari gi Visconti di Modrone su Bugatti davanti a Gino Cavanna. Nella successiva 8:30-10:00 Accoglienza nel parcheggio di via di Corgnate B ! "# $enice I edizione s’impose il toscano Clemente Biondetti su Bugatti nei confronti del (parte superiore) e verifiche presso ufficio turistico N 1929 L.Visconti di Modrone, Bugatti 35 bolognese Amedeo Ruggeri su Maserati. La terza ed ultima edizione del pe- 10:45 Accodamento alle vetture del primo gruppo 1930 Clemente Biondetti, Bugatti 35 M riodo pionieristico registrò il successo di Enzo Ferrari su Alfa Romeo 2300 e arrivo al Passo Penice K 1931 Enzo Ferrari, Alfa Romeo 8C 2300 sport. E fu il “canto del cigno” del campione modenese che doveva diventare 11:30 Sosta in Piazzale Enzo Ferrari e aperitivo J 1952 Gianni Cavallini, Fiat 500/C il “Drake” di Maranello. La gara riprese negli anni 1952 e 1953 con la formula 12:00 Prova culturale e rientro a Bobbio 1953 Giacomo Parietti, Fiat 500/S mista velocità e regolarità. Nel ‘54 la corsa si effettuò con la formula che l’ha 12:30 Esposizione vetture in piazza Duomo e pranzo I 1954 Camillo Luglio, Lancia Aurelia B20 16:00 Premiazioni sempre contraddistinta e cioè quella del miglior tempo impiegato e fu il ge- H 1961 Gianni Brichetti, W.R.E. -

1:18 CMC Jaguar C-Type Review

1:18 CMC Jaguar C-Type Review The year was 1935 when the Jaguar brand first leapt out of the factory gates. Founded in 1922 as the Swallow Sidecar Company by William Lyons and William Walmsley, both were motorcycle enthusiasts and the company manufactured motorcycle sidecars and automobile bodies. Walmsley was rather happy with the company’s modest success and saw little point in taking risks by expanding the firm. He chose to spend more and more time plus company money on making parts for his model railway instead. Lyons bought him out with a public stock offering and became the sole Managing Director in 1935. The company was then renamed to S.S. Cars Limited. After Walmsley had left, the first car to bear the Jaguar name was the SS Jaguar 2.5l Saloon released in September 1935. The 2.5l Saloon was one of the most distinctive and beautiful cars of the pre-war era, with its sleek, low-slung design. It needed a new name to reflect these qualities, one that summed up its feline grace and elegance with such a finely-tuned balance of power and agility. The big cat was chosen, and the SS Jaguar perfectly justified that analogy. A matching open-top two-seater called the SS Jaguar 100 (named 100 to represent the theoretical top speed of 100mph) with a 3.5 litre engine was also available. www.themodelcarcritic.com | 1 1:18 CMC Jaguar C-Type Review 1935 SS Jaguar 2.5l Saloon www.themodelcarcritic.com | 2 1:18 CMC Jaguar C-Type Review 1936 SS Jaguar 100 On 23rd March 1945, the shareholders took the initiative to rename the company to Jaguar Cars Limited due to the notoriety of the SS of Nazi Germany during the Second World War. -

At Ferrari's Steering Wheel "375 MM, 275 GTB, 330 GTC, 365 50 80 GTB/4 Et 512 BB")

Low High Lot Description estimate estimate Books P.Gary, C. Bedei, C.Moity: Au volant Ferrari "375 MM, 275 GTB, 330 GTC, 365 1 GTB/4 et 512 BB" (At Ferrari's steering wheel "375 MM, 275 GTB, 330 GTC, 365 50 80 GTB/4 et 512 BB"). Ed. La sirène (1ex.) 2 L.ORSINI. AUTO Historia Ferrari. Ed. E.P.A. (1ex.) 30 50 3 Auto Test Ferrari I - 1962/1971. Ed. E.P.A. (1ex.) 20 30 4 G. RANCATI: Enzo Ferrari. Ed. E.P.A. (1ex.) 80 100 5 D.PASCAL: Enzo Ferrari le Mythe (Enzo Ferrari the Myth). Ed. Ch. Massin (1ex.) 50 80 6 F.SABATES: Ferrari. Ed. Ch. Massin (1ex.) 20 30 7 Ferrari. Ed. Ceac (1ex.) 50 80 P. LYONS: Ferrari: Toute l'histoire, tous les Modèles (Ferrari: The whole History, all 8 20 30 the Models). Ed. E.P.A. (1ex.) 9 J.STARKEY. Ferrari 250 GT Berlinetta "Tour de France". Ed. Veloce (1ex.) 80 100 10 J.RIVES. Ferrari formule record. Ed. Solar (1ex.) 20 30 P.COCKERHAM. Ferrari: Le rêve automobile (Ferrari: the automobile dream). 11 20 30 Ed. Todtri (1ex.) J.M & D. LASTU. Ferrari miniatures sport, prototypes, 250GT et GTO. (Ferrari sport 12 miniatures, prototypes, 250 GT and GTO) Ed. E.P.A.Livres en Français 1/43 20 30 (1ex.) S. BELLU: Guide Ferrari - tous les modeles année par année (Ferrari Guide: all 13 20 30 the models year by year). Ed. E.P.A. (1ex.) A.PRUNET. La Légende Ferrari Sport et prototypes (The Ferrari legend - Sport 14 80 100 and Prototypes). -

EVERY FRIDAY Vol. 17 No.1 the WORLD's FASTEST MO·TOR RACE Jim Rathmann (Zink Leader) Wins Monza 500 Miles Race at 166.73 M.P.H

1/6 EVERY FRIDAY Vol. 17 No.1 THE WORLD'S FASTEST MO·TOR RACE Jim Rathmann (Zink Leader) Wins Monza 500 Miles Race at 166.73 m.p.h. -New 4.2 Ferrari Takes Third Place-Moss's Gallant Effort with the Eldorado Maserati AT long last the honour of being the big-engined machines roaring past them new machines, a \'-12, 4.2-litre and a world's fastest motor race has been in close company, at speeds of up to 3-litre V-6, whilst the Eldorado ice-cream wrested from Avus, where, in prewar 190 m.p.h. Fangio had a very brief people had ordered a V-8 4.2-litre car days, Lang (Mercedes-Benz) won at an outing, when his Dean Van Lines Special from Officine Maserati for Stirling Moss average speed of 162.2 m.p.h. Jim Rath- was eliminated in the final heat with fuel to drive. This big white machine was mann, driving the Zink Leader Special, pump trouble after a couple of laps; soon known amongst the British con- made Monza the fastest-ever venue !by tingent as the Gelati-Maserati! Then of winning all three 63-1ap heats for the course there was the Lister-based, quasi- Monza 500 Miles Race, with an overall single-seater machine of Ecurie Ecosse. speed of 166.73 m.p.h. By Gregor Grant The European challenge was completed Into second place came the 1957 win- Photography by Publifoto, Milan by two sports Jaguars, and Harry Schell ner, Jim Bryan (Belond A.P. -

Lewis the Unbreakable

IT’S ALL ABOUT THE PASSION ABU DHABI GP Issue 159 23 November 2014 Lewis the unbreakable LEADER 3 ON THE GRID BY JOE SAWARD 4 SNAPSHots 8 LEWIS HAMIltoN WORLD CHAMPION 20 IS MAttIAccI OUT AT FERRARI ? 22 DAMON HILL ON F1 SHOWDOWNS 25 FORMULA E 30 THE LA BAULE GRAND PRIX 38 THE SAMBA & TANGO CALENDAR 45 PETER NYGAARD’S 500TH GRAND PRIX 47 THE HACK LOOKS BACK 48 ABU DHABI - QUALIFYING REPORT 51 ABU DHABI - RACE REPORT 65 ABU DHABI - GP2/GP3 79 THE LAST LAP BY DAVID TREMAYNE 85 PARTING SHot 86 The award-winning Formula 1 e-magazine is brought to you by: David Tremayne | Joe Saward | Peter Nygaard With additional material from Mike Doodson | Michael Stirnberg © 2014 Morienval Press. All rights reserved. Neither this publication nor any part of it may be reproduced or transmitted in any form, or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior permission of Morienval Press. WHO WE ARE... ...AND WHAT WE THINK DAVID TREMAYNE is a freelance motorsport writer whose clients include The Independent and The Independent on Sunday newspapers. A former editor and executive editor of Motoring News and Motor Sport, he is a veteran of 25 years of Grands Prix reportage, and the author of more than 40 books on motorsport. He is the only three-time winner of the Guild of Motoring Writers’ Timo Makinen and Renault Awards for his books. His writing, on both current and historic issues, is notable for its soul and passion, together with a deep understanding of the sport and an encyclopaedic knowledge of its history. -

Le Mans (Not Just) for Dummies the Club Arnage Guide

Le Mans (not just) for Dummies The Club Arnage Guide to the 24 hours of Le Mans 2011 "I couldn't sleep very well last night. Some noisy buggers going around in automobiles kept me awake." Ken Miles, 1918 - 1966 Copyright The entire contents of this publication and, in particular of all photographs, maps and articles contained therein, are protected by the laws in force relating to intellectual property. All rights which have not been expressly granted remain the property of Club Arnage. The reproduction, depiction, publication, distr bution or copying of all or any part of this publication, or the modification of all or any part of it, in any form whatsoever is strictly forbidden without the prior written consent of Club Arnage (CA). Club Arnage (CA) hereby grants you the right to read and to download and to print copies of this document or part of it solely for your own personal use. Disclaimer Although care has been taken in preparing the information supplied in this publication, the authors do not and cannot guarantee the accuracy of it. The authors cannot be held responsible for any errors or omissions and accept no liability whatsoever for any loss or damage howsoever arising. All images and logos used are the property of Club Arnage (CA) or CA forum members or are believed to be in the public domain. This guide is not an official publication, it is not authorized, approved or endorsed by the race-organizer: Automobile Club de L’Ouest (A.C.O.) Mentions légales Le contenu de ce document et notamment les photos, plans, et descriptif, sont protégés par les lois en vigueur sur la propriété intellectuelle. -

BRDC Bulletin

BULLETIN BULLETIN OF THE BRITISH RACING DRIVERS’ CLUB DRIVERS’ RACING BRITISH THE OF BULLETIN Volume 30 No 2 • SUMMER 2009 OF THE BRITISH RACING DRIVERS’ CLUB Volume 30 No 2 2 No 30 Volume • SUMMER 2009 SUMMER THE BRITISH RACING DRIVERS’ CLUB President in Chief HRH The Duke of Kent KG Volume 30 No 2 • SUMMER 2009 President Damon Hill OBE CONTENTS Chairman Robert Brooks 04 PRESIDENT’S LETTER 56 OBITUARIES Directors 10 Damon Hill Remembering deceased Members and friends Ross Hyett Jackie Oliver Stuart Rolt 09 NEWS FROM YOUR CIRCUIT 61 SECRETARY’S LETTER Ian Titchmarsh The latest news from Silverstone Circuits Ltd Stuart Pringle Derek Warwick Nick Whale Club Secretary 10 SEASON SO FAR 62 FROM THE ARCHIVE Stuart Pringle Tel: 01327 850926 Peter Windsor looks at the enthralling Formula 1 season The BRDC Archive has much to offer email: [email protected] PA to Club Secretary 16 GOING FOR GOLD 64 TELLING THE STORY Becky Simm Tel: 01327 850922 email: [email protected] An update on the BRDC Gold Star Ian Titchmarsh’s in-depth captions to accompany the archive images BRDC Bulletin Editorial Board 16 Ian Titchmarsh, Stuart Pringle, David Addison 18 SILVER STAR Editor The BRDC Silver Star is in full swing David Addison Photography 22 RACING MEMBERS LAT, Jakob Ebrey, Ferret Photographic Who has done what and where BRDC Silverstone Circuit Towcester 24 ON THE UP Northants Many of the BRDC Rising Stars have enjoyed a successful NN12 8TN start to 2009 66 MEMBER NEWS Sponsorship and advertising A round up of other events Adam Rogers Tel: 01423 851150 32 28 SUPERSTARS email: [email protected] The BRDC Superstars have kicked off their season 68 BETWEEN THE COVERS © 2009 The British Racing Drivers’ Club. -

Le Rapt De Fangio À Cuba, Comme Le Raconta Maurice Trintignant

Le rapt de Fangio à Cuba, comme le raconta Maurice Trintignant Par Michel Porcheron On est à « La Cave du Pétoulet », rue Emile-Jamais à Nîmes, un jour de mars 1958. Il y a là quelques clients fidèles, surtout des ménagères qui font leurs courses avant le repas de midi. Un fort mistral souffle ce matin-là, « La Cave du Pétoulet » est d’autant plus accueillante. « Pétoulet » c’est le surnom de Maurice Trintignant (1917-2005, Nîmes), coureur (ou pilote) automobile fameux, heureux vigneron, spécialisé plutôt dans le rosé, tiré de ses 45 hectares, au Mas d’Arnaud, entre Vergèze et Vauvert, dans la campagne gardoise. Depuis 1930 Maurice est l’oncle de Jean-Louis. Trintignant est rentré de La Havane où il a participé au 2E Grand Prix de Cuba (24 coureurs) le lundi 24 février, au volant de la Maserati de… Fangio, empêché. Et pour cause, le quintuple champion du monde de Formule 1, vainqueur du 1 er GP de Cuba l’année précédente, a été enlevé la veille, dimanche, par un groupe de rebelles cubains du Mouvement castriste du 26 Juillet. Fidel Castro, Raul, le Che, Camilo Cienfuegos et leurs hommes (combien ? peu) sont quelque part dans la Sierra Maestra. Fangio L’Argentin Juan Manuel Fangio (1911-1995) sera « retenu patriotiquement » quelque 26 heures. Si le compte est bon, le groupe était formé de quelque 26 hommes et femmes (7) ça ne s’invente pas. Ce matin de fin mars 1958, « Pétoulet » raconte pour l’assistance du jour. Le journaliste parisien Georges Pagnoud n’est pas là par hasard. -

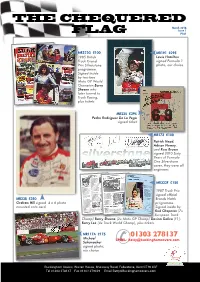

The Chequered Flag

THE CHEQUERED March 2016 Issue 1 FLAG F101 MR322G £100 MR191 £295 1985 British Lewis Hamilton Truck Grand signed Formula 1 Prix Silverstone photo, our choice programme. Signed inside by two-time Moto GP World Champion Barry Sheene who later turned to Truck Racing, plus tickets MR225 £295 Pedro Rodriguez De La Vega signed ticket MR273 £100 Patrick Head, Adrian Newey, and Ross Brawn signed 2010 Sixty Years of Formula One Silverstone cover, they were all engineers MR322F £150 1987 Truck Prix signed official MR238 £350 Brands Hatch Graham Hill signed 4 x 6 photo programme. mounted onto card Signed inside by Rod Chapman (7x European Truck Champ) Barry Sheene (2x Moto GP Champ) Davina Galica (F1), Barry Lee (4x Truck World Champ), plus tickets MR117A £175 01303 278137 Michael EMAIL: [email protected] Schumacher signed photo, our choice Buckingham Covers, Warren House, Shearway Road, Folkestone, Kent CT19 4BF 1 Tel 01303 278137 Fax 01303 279429 Email [email protected] SIGNED SILVERSTONE 2010 - 60 YEARS OF F1 Occassionally going round fairs you would find an odd Silverstone Motor Racing cover with a great signature on, but never more than one or two and always hard to find. They were only ever on sale at the circuit, and were sold to raise funds for things going on in Silverstone Village. Being sold on the circuit gave them access to some very hard to find signatures, as you can see from this initial selection. MR261 £30 MR262 £25 MR77C £45 Father and son drivers Sir Jackie Jody Scheckter, South African Damon Hill, British Racing Driver, and Paul Stewart. -

Travel Destinations Essential Guide to the Le Mans Classic

www.traveldestinations.co.uk LeMans Classic YOUR ESSENTIAL GUIDE 2018 Welcome Welcome to Le Mans Classic 2018 Travel Destinations is the UK’s leading tour 2018 sees the 9th running of the Le Mans For Le Mans Classic 2018, we have operator for the Le Mans Classic & the Le Classic and it promises to be the biggest 4 different on-circuit accommodation areas Mans 24 hours race. We are committed to yet. The first event in 2002 was watched exclusive to Travel Destinations customers; provide you, our highly valued customers, by 30,000 spectators. This year 150,000 + camping at Hunaudieres and Porsche with the very best customer service and motoring enthusiasts are expected to Curves, Event Tents at Beausejour and peace of mind with the government backed visit the circuit over the Le Mans Classic our Flexotel Village at Antares Sud. financial security for your booking through weekend. Car clubs have always played a our membership of ABTA, ATOL & AITO. key role in the Le Mans Classic. The inside Details of each of these products will be of the “Bugatti Circuit” is turned in to a giant included separately in your travel packs. This year, as well as our popular “Essential car club car park for the duration of the Guide”, we are pleased to offer all Our staff will be available at all the various event, forming the largest classic car display locations to assist with check-in and help customers our circuit assistance helpline in Europe. (You will find this enclosed in your travel throughout the weekend. -

Alpine En Endurance 1963-1978, Les Années De Légende

TRIMESTRIEL N° 2 LAl'Authentique REVUE OFFICIELLE DE LA FÉDÉRATION FRANÇAISE DES VÉHICULES D’ÉPOQUE GRAND DU SPORT UTILITAIRE LÉGER HISTOIRE DE MARQUE Henri Pescarolo, 1939-1954, et la 2 CV Koelher-Escoffier, les longues nuits du Mans devint camionnette le sport avant tout SAGA AUTOMOBILE Ford T en France, pionnière d’outre-atlantique ALPINE EN ENDURANCE 1963-1978, LES ANNÉES DE LÉGENDE LOI ET RÈGLEMENTS L 16034 - 2 - F: 7,00 - RD Copies, répliques, kit-cars et véhicules transformés JUIN - JUILLET - AOUT 2018 EDITO raison. Je me contente de constater, et, au fond de moi, je me dis que je manque peut-être quelque chose en refusant d’affronter l’hiver au volant d’une Ancienne. Je ne suis pas un restaurateur, la peur de mal faire m’empêche de toucher à la mécanique. Je me contente de soigner l’apparence, le chiffon microfibre et la Nénette à portée de main. Il est vrai aussi que je n’ai guère le loisir de m’occuper de mes véhicules. J’ai à peine le temps de les faire rouler régulièrement, mais ceci est une autre histoire… Pourquoi vous parler de mes soucis de collectionneur ? Pour, en fait, vous dire que, quelle que soit la façon de l’aborder, notre plaisir de posséder et de faire rouler nos véhicules est bien réel. Alors, si quelqu’un, pour un quelconque motif pseudo-écologique et franchement démagogique, s’avise de m’empêcher de vivre ma passion, il me trouvera sur sa route ! Depuis quelques mois, nous avons successivement vu les prix des carburants, des péages, des assurances et des stationnements augmenter de façon in- considérée. -

Facts and Figures of the 24 Hours of Le Mans

2018 Le Mans 24 Hours Press Kit - Facts and Figures Facts and Figures of the 24 Hours of Le Mans A race that lasts 24 hours stretches many limits. The 95-year-long history of the 24 Hours of Le Mans is full of extraordinary feats. These figures help appreciate the magnitude of the race. High-Performance Culture 251.882 kph The average speed of the fastest lap in the history of the 24 Hours of Le Mans, recorded in 2017 by Kamui Kobayashi in the Toyota TS050 Hybrid during qualifying. He completed the 13.629-km lap in 3:14.791. 405 kph The top speed attained on the circuit by Roger Dorchy in a WM P88 on the Mulsanne Straight in 1988. This record has little chance of ever being broken as two chicanes have been installed on the straight since then. 5410.713 km The longest distance covered in the 24 hours (397 laps of the circuit), by the Audi R15+ TDI that won the race in 2010 in the hands of Romain Dumas, Timo Bernhard and Mike Rockenfeller. 1,000 hp The maximum output of the Toyota TS050 Hybrid LMP1 which has a twin-turbo internal combustion engine and two electric motors. 878 kg The minimum weight for an LMP1 hybrid, which is the same as a Smart Fortwo! Impressive Records 9 wins (driver) The record number of outright victories for a driver is held by Tom Kristensen, known as Mr Le Mans, who contended the race from 1997 to 2014. 33 participations The record for the most Le Mans races is held by Henri Pescarolo, who entered a further 12 times as manager of Pescarolo Sport.