12. Towards an Aesthetics for Interaction

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

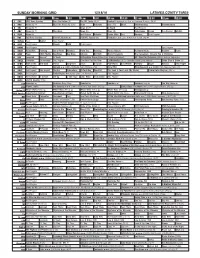

Sunday Morning Grid 12/18/16 Latimes.Com/Tv Times

SUNDAY MORNING GRID 12/18/16 LATIMES.COM/TV TIMES 7 am 7:30 8 am 8:30 9 am 9:30 10 am 10:30 11 am 11:30 12 pm 12:30 2 CBS CBS News Sunday Face the Nation (N) The NFL Today (N) Å Football Pittsburgh Steelers at Cincinnati Bengals. (N) Å 4 NBC News (N) Å Meet the Press (N) (TVG) News Naturally Give (TVY) Heart Snowboarding Snowboarding 5 CW News (N) Å News (N) Å In Touch Paid Program 7 ABC News (N) Å This Week News (N) News (N) Jack Hanna Ocean Sea Rescue Wildlife 9 KCAL News (N) Joel Osteen Schuller Pastor Mike Paid Amazing Paid Program 11 FOX Fox News Sunday FOX NFL Kickoff (N) FOX NFL Sunday (N) Football Detroit Lions at New York Giants. (N) Å 13 MyNet Paid Matter Paid Program 18 KSCI Paid Program Church Faith Paid Program 22 KWHY Paid Program Paid Program 24 KVCR Paint With Painting Joy of Paint Wyland’s Paint This Painting Alsace-Hubert Heirloom Meals Healthy Kevin 28 KCET Peep 1001 Nights Bug Bites Bug Bites Edisons Biz Kid$ Mario Frangoulis The Carpenters: Close to You & Christmas 30 ION Jeremiah Youssef In Touch A Christmas Truce (2015) Craig Olejnik, Ali Liebert. All I Want for Christmas (2013) Melissa Sagemiller. 34 KMEX Conexión En contacto Paid Program Grandma Got Run Over La Madrecita (1973, Comedia) María Elena Velasco. Como Dice el Dicho (N) 40 KTBN Walk in the Win Walk Prince Carpenter Jesse In Touch PowerPoint It Is Written Pathway Super Kelinda John Hagee 46 KFTR Paid Program Jumanji ›› (1995, Fantasía) Robin Williams. -

Roy Lichtenstein's European Rise to Fame, 1963-1966 Courbet Americano

A Modern, American Courbet: Roy Lichtenstein’s European Rise to Fame, 1963-1966 Courbet americano: a ascensão de Roy Lichtestein à fama na Europa, 1963-1966 Dra. Catherine Dossin Como citar: DOSSIN, C.. A Modern, American Courbet: Roy Lichtenstein’s European Rise to Fame, 1963-1966. MODOS. Revista de História da Arte. Campinas, v. 1, n.1, p.113-126, jan. 2017. Disponível em: ˂http://www.publionline.iar.unicamp.br/index.php/mod/article/view /732/692˃ Imagem: Roy Lichtenstein na 32ª Bienal de Veneza, 1964, fonte: http://www.labiennale.org/en/photocenter/biennale2.html?back=true A Modern, American Courbet: Roy Lichtenstein’s European Rise to Fame, 1963-1966 Courbet americano: a ascensão de Roy Lichtestein à fama na Europa, 1963-1966 Dra. Catherine Dossin * Abstract Taking on Roy Lichtenstein’s European rise to fame, my paper describes how his work arrived in Western Europe during the 1963 Crisis of Abstract, when Europeans were turning their attention to Realism anew. It then explains that they appreciated his engagement with contemporary reality. Moreover, Lichtenstein’s popular imagery, colorful palette, and mechanized style appealed to them as a reflection of US-American civilization, whose influence was then at its pinnacle in Europe. They regarded him as a modern, American Courbet. His success was thus less “the triumph of American art” than the triumph of a European idea of the United States. Keywords Roy Lichtenstein; Pop Art; American Art; Realism; Cultural Transfers. Resumo Partindo do sucesso de Roy Lichtenstein na Europa, meu artigo descreve como seu trabalho chegou na Europa ocidental durante a crise da abstração em 1963 (Crisis of Abstract), quando os europeus estavam voltando sua atenção para um novo Realismo. -

Konstrukce Femininity V Umělecké Tvorbě Pop Artu

Filozofická fakulta Univerzity Palackého v Olomouci Katedra mediálních a kulturálních studií a ţurnalistiky KONSTRUKCE FEMININITY V UMĚLECKÉ TVORBĚ POP ARTU Construction of Femininity in Artistic Creation of Pop Art Magisterská diplomová práce Kateřina Vojkůvková Vedoucí práce: Mgr. Eva Chlumská Olomouc 2017 Prohlašuji, ţe jsem předloţenou magisterskou diplomovou práci vypracovala samostatně a ţe jsem uvedla veškeré pouţité zdroje a prameny. Celkový rozsah práce je 180 560 znaků (vč. mezer). V Olomouci dne 19. 4. 2017 ……….……………………………. Na tomto místě bych ráda poděkovala vedoucí práce Mgr. Evě Chlumské za uţitečné rady a připomínky při zpracování této práce. A dále mé rodině, která mne po celou dobu studia podporovala. Abstrakt Tato magisterská diplomová práce je zaměřena na zmapování způsobu stereotypního znázornění ţeny v umělecké tvorbě pop artu, konkrétně jeho anglické a americké větve v době vrcholu mezi lety 1960 a 1965. Autoři pop artu se orientovali na soudobou konzumní společnost a komponovali její prvky do svých vizuálních vyjádření. Problematizován je tedy primárně způsob ztvárnění ţenské postavy a skladba objektů, které ji doplňují. Klíčová slova: pop art, ţena, gender, stereotyp, obraz, masová kultura, kýč, kvalitativní analýza. Abstract This thesis is focused on mapping the way of stereotypical representation of woman in pop art, specifically British and American branches during peak between 1960 and 1965. The authors of the pop art prefer the contemporary consumer society and its composing elements in their visual expression. Problematised is therefore primarily a way of rendering the female body and composion of objects that complement it. Key words: Pop art, Woman, Gender, Stereotype, Painting, Mass Culture, Kitsch, Qualitative Analysis. 1. -

Di Lichtenstein Artista Anche Nelle Cifre

01CUL02A0110 FLOWPAGE ZALLCALL 12 21:49:08 09/30/97 CULTURA eSOCIETÀ l’Unità2 3 Mercoledì 1 ottobre 1997 Con Warhol, Dine, Oldenburg, Wesselmann,Rosenquist, è stato frai protagonisti della «Pop Art» newyor- kese (più formalmente educata ri- Pop Art spetto a quella esuberante e vitalisti- ca manifestatasi in altre aree norda- Dalle strade mericane). RoyLichtenstein (nato a New York nel 1923) si è affermato ai musei dall’inizio degli anni Sessanta attra- verso un’impostazione molto chiara della propria pittura, lucidamente E ritorno trasferendonelladimensionepittori- calesuggestionideifumetti,siacome Un «erede» di immagini, sia sopratutto come im- Lichtenstein? Non pianto linguistico. Suo riferimento cercatelo nelle gallerie era il repertorio dei disegnatori di tra- d’arte, lo trovate nelle dizione d’intenzione narrativa reali- strade. Non sarà proprio stica: i vari Dick Floyd, Don Sher- Lichtenstein, ma ci wood,GeorgeWunder,ecc. assomiglia molto. Si Aveva lavorato come disegnatore chiama Roberto industriale, e forse la nettezza ed es- Baldazzini, è uno dei più senzialitàdelsuoparticolaremododi bravi autori di fumetti figurare ne conservava l’imprinting. italiano ma firma anche la Come pittore emerge nei primi anni campagna pubblicitaria Cinquanta, impegnandosi in modi della Tim per i telefoni di immaginazione folcloristica, nella cellulari. I suoi manifesti a tradizione dell’American scene (co- fumetti con ragazzi e wboy, indiani, sceriffi, ecc). Nel ragazze che 1957 si orienta verso l’espressioni- propagandano tariffe, smo astratto informale, e in tale vantaggi e sconti degli linguaggio occasionalmente co- abbonamenti Telecom, mincia a sperimentare l’inserimen- tappezzano le strade di to di spunti di immagini già de- tutta Italia. Tra i quadri del sunte da «cartoons». -

Roy Lichtenstein a Pop Art

Roy Lichtenstein a Pop Art BcA. Helena Kučerová Magisterská práce 2007 ABSTRAKT Ve své magisterské práci se zabývám uměním šedesátých let dvacátého století. V první části se věnuji Pop Artu, jeho filozofii, námětech a historických souvislostech. Druhá část navazuje životem a dílem jednoho z nejvýznamnějších představitelů tohoto hnutí, Roye Lichtensteina. Klíčová slova: Pop Art, Roy Lichtenstein, Benday Dots, komiks, umění ABSTRACT I deal with art of sixties in my diploma thesis. I attend to Pop Art movement, philosophy, subject matters and historical aspects in the first chapter. The second part is continues with life and art one of the most important and popular artist of this movement – Roy Lichtenstein. Keywords: Pop Art, Roy Lichtenstein, Benday Dots, comics, art Prohlašuji, že jsem magisterskou práci zpracovala samostatně a použitou literaturu a zdroje jsem citovala. V Praze dne 8. 5. 2007 BcA. Helena Kučerová OBSAH ÚVOD....................................................................................................................................7 I TEORETICKÁ ČÁST ...............................................................................................8 1 POP ART.....................................................................................................................9 1.1 CO JE POP? ...........................................................................................................9 1.2 NÁMĚTY A MYŠLENKY ........................................................................................11 1.3 POP -

12. Towards an Aesthetics for Interaction

12. towards an aesthetics for interaction experience is determined by meaning learning objectives After reading this chapter you should have an understanding of the model underlying game playing, and the role of narratives in interaction. Fur- thermore, you might have an idea of how to define aesthetic meaning in a cultural context, and apply your understanding to the creative development of meaningful interactive systems. As in music, the meaning of interactive applications is determined, not only by its sensory appearance, but to a high extent by the structure and functionality of the application. This observation may, also, explain, why narratives become more and more important in current video games, namely in providing a meaningful context for possible user actions. In this chapter, we take an interactive game-model extended with narrative functionality as a starting point to explore the aesthetics of interactive applica- tions. In section 12.1, we will introduce a model for interactive video games, and in section 12.2 we will present a variety of rules for the construction of narratives in a game context. Finally, in section 12.3, we will characterize the notion of meaning from a traditional semiotics perspective, which we will then apply in the context of games and interactive multimedia applications. 1 1 2 towards an aesthetics for interaction 12.1 a game model game theory perspectives • system – (formal) set of rules • relation – between player and game (affectionate) • context – negotiable relation with ’real world’ dictionary 2 classic game model • rules: formal system • outcome: variable and quantifiable • value: different valorisation assignments • effort: in order to influence the outcome • attachment: emotionally attached to outcome (hooked) • consequences: optional and negotiable (profit?) rules vs fiction Game fiction is ambiguous, optional and imagined by the player in uncontrollable and unpredictable ways, but the emphasis on fictional worlds may be the strongest innovation of the video game.