Assessment of Microscopic Hematuria in Adults MARY M

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Bladder Cancer Early Detection, Diagnosis, and Staging Detection and Diagnosis

cancer.org | 1.800.227.2345 Bladder Cancer Early Detection, Diagnosis, and Staging Detection and Diagnosis Finding cancer early, when it's small and hasn't spread, often allows for more treatment options. Some early cancers may have signs and symptoms that can be noticed, but that's not always the case. ● Can Bladder Cancer Be Found Early? ● Bladder Cancer Signs and Symptoms ● Tests for Bladder Cancer Stages and Outlook (Prognosis) After a cancer diagnosis, staging provides important information about the extent (amount) of cancer in the body and the likely response to treatment. ● Bladder Cancer Stages ● Survival Rates for Bladder Cancer Questions to Ask About Bladder Cancer Here are some questions you can ask your cancer care team to help you better understand your cancer diagnosis and treatment options. ● Questions To Ask About Bladder Cancer 1 ____________________________________________________________________________________American Cancer Society cancer.org | 1.800.227.2345 Can Bladder Cancer Be Found Early? Bladder cancer can sometimes be found early -- when it's small and hasn't spread beyond the bladder. Finding it early improves your chances that treatment will work. Screening for bladder cancer Screening is the use of tests or exams to look for a disease in people who have no symptoms. At this time, no major professional organizations recommend routine screening of the general public for bladder cancer. This is because no screening test has been shown to lower the risk of dying from bladder cancer in people who are at average risk. Some providers may recommend bladder cancer tests for people at very high risk, such as: ● People who had bladder cancer before ● People who had certain birth defects of the bladder ● People exposed to certain chemicals at work Tests that might be used to look for bladder cancer Tests for bladder cancer look for different substances and/or cancer cells in the urine. -

Clinical Usefulness of Urine Cytology in the Detection of Bladder Tumors in Patients with Neurogenic Lower Urinary Tract Dysfunction

Journal name: Research and Reports in Urology Article Designation: ORIGINAL RESEARCH Year: 2017 Volume: 9 Research and Reports in Urology Dovepress Running head verso: Pannek et al Running head recto: Cytology for bladder tumor detection in neurogenic bladder open access to scientific and medical research DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.2147/RRU.S148429 Open Access Full Text Article ORIGINAL RESEARCH Clinical usefulness of urine cytology in the detection of bladder tumors in patients with neurogenic lower urinary tract dysfunction Jürgen Pannek Introduction: Screening for bladder cancer in patients with neurogenic lower urinary tract Franziska Rademacher dysfunction is a challenge. Cystoscopy alone is not sufficient to detect bladder tumors in this Jens Wöllner patient group. We investigated the usefulness of combined cystoscopy and urine cytology. Materials and methods: By a systematic chart review, we identified all patients with neuro- Neuro-Urology, Swiss Paraplegic Center, Nottwil, Switzerland genic lower urinary tract dysfunction who underwent combined cystoscopy and urine cytology testing. In patients with suspicious findings either in cytology or cystoscopy, transurethral resection was performed. Results: Seventy-nine patients (age 54.8±14.3 years, 38 female, 41 male) were identified; 44 of these used indwelling catheters. Cystoscopy was suspicious in 25 patients and cytology was suspicious in 17 patients. Histologically, no tumor was found in 15 patients and bladder cancer was found in 6 patients. Sensitivity for both cytology and cystoscopy was 83.3%; specificity was 43.7% for cytology and 31.2% for cystoscopy. One bladder tumor was missed by cytology and three tumors were missed by cystoscopy. If a biopsy was taken only if both findings were suspicious, four patients would have been spared the procedure, and one tumor would not have been diagnosed. -

Prevalence of Microhematuria in Renal Colic and Urolithiasis: a Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis

Minotti et al. BMC Urology (2020) 20:119 https://doi.org/10.1186/s12894-020-00690-7 RESEARCH ARTICLE Open Access Prevalence of microhematuria in renal colic and urolithiasis: a systematic review and meta-analysis Bruno Minotti1* , Giorgio Treglia2, Mariarosa Pascale3, Samuele Ceruti4, Laura Cantini5, Luciano Anselmi5 and Andrea Saporito5 Abstract Background: This systematic review and meta-analysis aims to investigate the prevalence of microhematuria in patients presenting with suspected acute renal colic and/or confirmed urolithiasis at the emergency department. Methods: A comprehensive literature search was conducted to find relevant data on prevalence of microhematuria in patients with suspected acute renal colic and/or confirmed urolithiasis. Data from each study regarding study design, patient characteristics and prevalence of microhematuria were retrieved. A random effect-model was used for the pooled analyses. Results: Forty-nine articles including 15′860 patients were selected through the literature search. The pooled microhematuria prevalence was 77% (95%CI: 73–80%) and 84% (95%CI: 80–87%) for suspected acute renal colic and confirmed urolithiasis, respectively. This proportion was much higher when the dipstick was used as diagnostic test (80 and 90% for acute renal colic and urolithiasis, respectively) compared to the microscopic urinalysis (74 and 78% for acute renal colic and urolithiasis, respectively). Conclusions: This meta-analysis revealed a high prevalence of microhematuria in patients with acute renal colic (77%), including those with confirmed urolithiasis (84%). Intending this prevalence as sensitivity, we reached moderate values, which make microhematuria alone a poor diagnostic test for acute renal colic or urolithiasis. Microhematuria could possibly still important to assess the risk in patients with renal colic. -

Management of the Incidental Renal Mass on CT: a White Paper of the ACR Incidental Findings Committee

ORIGINAL ARTICLE Management of the Incidental Renal Mass on CT: A White Paper of the ACR Incidental Findings Committee Brian R. Herts, MDa, Stuart G. Silverman, MDb, Nicole M. Hindman, MDc, Robert G. Uzzo, MDd, Robert P. Hartman, MDe, Gary M. Israel, MD f, Deborah A. Baumgarten, MD, MPHg, Lincoln L. Berland, MDh, Pari V. Pandharipande, MD, MPHi Abstract The ACR Incidental Findings Committee (IFC) presents recommendations for renal masses that are incidentally detected on CT. These recommendations represent an update from the renal component of the JACR 2010 white paper on managing incidental findings in the adrenal glands, kidneys, liver, and pancreas. The Renal Subcommittee, consisting of six abdominal radiologists and one urologist, developed this algorithm. The recommendations draw from published evidence and expert opinion and were finalized by informal iterative consensus. Each flowchart within the algorithm describes imaging features that identify when there is a need for additional imaging, surveillance, or referral for management. Our goal is to improve quality of care by providing guidance for managing incidentally detected renal masses. Key Words: Kidney, renal, small renal mass, cyst, Bosniak classification, incidental finding J Am Coll Radiol 2017;-:---. Copyright Ó 2017 American College of Radiology OVERVIEW OF THE ACR INCIDENTAL Findings Committee (IFC) generated its first white paper FINDINGS PROJECT in 2010, addressing four algorithms for managing inci- The core objectives of the Incidental Findings Project are dental pancreatic, adrenal, kidney, and liver findings [1]. to (1) develop consensus on patient characteristics and imaging features that are required to characterize an THE CONSENSUS PROCESS: THE INCIDENTAL incidental finding, (2) provide guidance to manage such RENAL MASS ALGORITHM findings in ways that balance the risks and benefits to The current publication represents the first revision of the patients, (3) recommend reporting terms that reflect the IFC’s recommendations on incidental renal masses. -

A Cross Sectional Study Ofrenal Involvement in Tuberous Sclerosis

480 Med Genet 1996;33:480-484 A cross sectional study of renal involvement in tuberous sclerosis J Med Genet: first published as 10.1136/jmg.33.6.480 on 1 June 1996. Downloaded from J A Cook, K Oliver, R F Mueller, J Sampson Abstract There are two characteristic types of renal Renal disease is a frequent manifestation involvement in persons with TSC. (1) An- oftuberous sclerosis (TSC) and yet little is giomyolipomas. These are benign neoplasms known about its true prevalence or natural composed of mature adipose tissue, thick history. We reviewed the notes of 139 walled blood vessels, and smooth muscle in people with TSC, who had presented with- varying proportions. In the general population out renal symptoms, but who had been they are a rare finding affecting predominantly investigated by renal ultrasound. In- women (80%) in the third to fifth decade. formation on the frequency, type, and About 50% of people with angiomyolipomas symptomatology of renal involvement was have no stigmata of TSC and usually have retrieved. a large, single angiomyolipoma.6 In TSC the The prevalence ofrenal involvement was angiomyolipomas tend to be small, multiple, 61%. Angiomyolipomas were detected in and bilateral.7 Stillwell et al7 suggested that 49%, renal cysts in 32%, and renal car- there was an increase in the prevalence of cinoma in 2-2%. The prevalence of an- angiomyolipomas with age but only a limited giomyolipoma was positively correlated number of persons with TSC were studied. with age, compatible with a two hit aeti- (2) Renal cysts. These have a characteristic ology. -

ACR Appropriateness Criteria: Indeterminate Renal Mass

Revised 2020 American College of Radiology ACR Appropriateness Criteria® Indeterminate Renal Mass Variant 1: Indeterminate renal mass. No contraindication to either iodinated CT contrast or gadolinium- based MR intravenous contrast. Initial imaging. Procedure Appropriateness Category Relative Radiation Level US abdomen with IV contrast Usually Appropriate O MRI abdomen without and with IV contrast Usually Appropriate O CT abdomen without and with IV contrast Usually Appropriate ☢☢☢☢ US kidneys retroperitoneal May Be Appropriate O MRI abdomen without IV contrast May Be Appropriate O CT abdomen with IV contrast May Be Appropriate ☢☢☢ CT abdomen without IV contrast May Be Appropriate ☢☢☢ CTU without and with IV contrast May Be Appropriate ☢☢☢☢ Arteriography kidney Usually Not Appropriate ☢☢☢ Radiography intravenous urography Usually Not Appropriate ☢☢☢ Biopsy renal mass Usually Not Appropriate Varies MRU without and with IV contrast Usually Not Appropriate O Variant 2: Indeterminate renal mass. Contraindication to both iodinated CT and gadolinium-based MR intravenous contrast. Initial imaging. Procedure Appropriateness Category Relative Radiation Level US abdomen with IV contrast Usually Appropriate O US kidneys retroperitoneal Usually Appropriate O MRI abdomen without IV contrast Usually Appropriate O CT abdomen without IV contrast May Be Appropriate ☢☢☢ Arteriography kidney Usually Not Appropriate ☢☢☢ Radiography intravenous urography Usually Not Appropriate ☢☢☢ Biopsy renal mass Usually Not Appropriate Varies MRI abdomen without and with IV contrast Usually Not Appropriate O MRU without and with IV contrast Usually Not Appropriate O CT abdomen with IV contrast Usually Not Appropriate ☢☢☢ CT abdomen without and with IV contrast Usually Not Appropriate ☢☢☢☢ CTU without and with IV contrast Usually Not Appropriate ☢☢☢☢ ACR Appropriateness Criteria® 1 Indeterminate Renal Mass Variant 3: Indeterminate renal mass. -

EAU Guidelines on the Diagnosis and Treatment of Urothelial Carcinoma in Situ Adrian P.M

European Urology European Urology 48 (2005) 363–371 EAU Guidelines EAU Guidelines on the Diagnosis and Treatment of Urothelial Carcinoma in Situ Adrian P.M. van der Meijdena,*, Richard Sylvesterb, Willem Oosterlinckc, Eduardo Solsonad, Andreas Boehlee, Bernard Lobelf, Erkki Rintalag for the EAU Working Party on Non Muscle Invasive Bladder Cancer aDepartment of Urology, Jeroen Bosch Hospital, Nieuwstraat 34, 5211 NL ’s-Hertogenbosch, The Netherlands bEORTC Data Center, Brussels, Belgium cDepartment of Urology, University Hospital Ghent, Ghent, Belgium dDepartment of Urology, Instituto Valenciano de Oncologia, Valencia, Spain eDepartment of Urology, Helios Agnes Karll Hospital, Bad Schwartau, Germany fDepartment of Urology, Hopital Ponchaillou, Rennes, France gDepartment of Urology, Helsinki University Hospital, Helsinki, Finland Accepted 13 May 2005 Available online 13 June 2005 Abstract Objectives: On behalf of the European Association of Urology (EAU), guidelines for the diagnosis, therapy and follow-up of patients with urothelial carcinoma in situ (CIS) have been established. Method: The recommendations in these guidelines are based on a recent comprehensive overview and meta-analysis in which two panel members have been involved (RS and AVDM). A systematic literature search was conducted using Medline, the US Physicians’ Data Query (PDQ), the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials, and reference lists in trial publications and review articles. Results: Recommendations are provided for the diagnosis, conservative and radical surgical treatment, and follow- up of patients with CIS. Levels of evidence are influenced by the lack of large randomized trials in the treatment of CIS. # 2005 Elsevier B.V. All rights reserved. Keywords: Bladder cancer; Carcinoma in situ; Bacillus Calmette-Guerin; Chemotherapy; Diagnosis; Treatment; Follow up 1. -

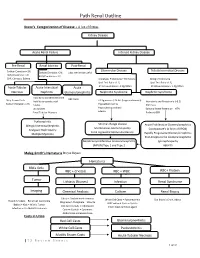

Path Renal Outline

Path Renal Outline Krane’s Categorization of Disease + A lot of Extras Kidney Disease Acute Renal Failure Intrinsic Kidney Disease Pre‐Renal Renal Intrinsic Post‐Renal Sodium Excretion <1% Glomerular Disease Tubulointerstitial Disease Sodium Excretion < 1% Sodium Excretion >2% Labs aren’t that useful BUN/Creatinine > 20 BUN/Creatinine < 10 CHF, Cirrhosis, Edema Urinalysis: Proteinuria + Hematuria Benign Proteinuria Spot Test Ratio >1.5, Spot Test Ratio <1.5, Acute Tubular Acute Interstitial Acute 24 Urine contains > 2.0g/24hrs 24 Urine contains < 1.0g/24hrs Necrosis Nephritis Glomerulonephritis Nephrotic Syndrome Nephritic Syndrome Inability to concentrate Urine RBC Casts Dirty Brown Casts Inability to secrete acid >3.5g protein / 24 hrs (huge proteinuria) Hematuria and Proteinuria (<3.5) Sodium Excretion >2% Edema Hypoalbuminemia RBC Casts Hypercholesterolemia Leukocytes Salt and Water Retention = HTN Focal Tubular Necrosis Edema Reduced GFR Pyelonephritis Minimal change disease Allergic Interstitial Nephritis Acute Proliferative Glomerulonephritis Membranous Glomerulopathy Analgesic Nephropathy Goodpasture’s (a form of RPGN) Focal segmental Glomerulosclerosis Rapidly Progressive Glomerulonephritis Multiple Myeloma Post‐Streptococcal Glomerulonephritis Membranoproliferative Glomerulonephritis IgA nephropathy (MPGN) Type 1 and Type 2 Alport’s Meleg‐Smith’s Hematuria Break Down Hematuria RBCs Only RBC + Crystals RBC + WBC RBC+ Protein Tumor Lithiasis (Stones) Infection Renal Syndrome Imaging Chemical Analysis Culture Renal Biopsy Calcium -

Management of the Nephrotic Syndrome GAVIN C

Arch Dis Child: first published as 10.1136/adc.43.228.257 on 1 April 1968. Downloaded from Personal Practice* Arch. Dis. Childh., 1968, 43, 257. Management of the Nephrotic Syndrome GAVIN C. ARNEIL From the Department of Child Health, University of Glasgow The nephrotic syndrome may be defined as gross (3) Idiopathic nephrosis. This may be re- proteinuria, predominantly albuminuria, with con- garded either as a primary disease, or as a secondary sequent selective hypoproteinaemia; usually accom- disorder, with the primary cause or causes still panied by oedema, ascites, and hyperlipaemia, and unknown. It is the common form of nephrosis in sometimes by systemic hypertension, azotaemia, or childhood, but the less common in adult patients. excessive erythrocyturia. Unless otherwise specified, the present discussion concerns idiopathic nephrosis. Grouping of Nephrotic Syndrome The syndrome falls into three groups. Assessment of the Case Full history and examination helps to exclude (1) Congenital nephrosis. A group of dis- many secondary forms of the disease. Blood orders present at and presenting soon after birth, pressure is recorded employing as broad a cuff as which are familial and may be acquired or inherited. practicable, and the width of the cuff used is Persistent oedema attracts attention in the first recorded as of importance in comparative estima- weeks of life. The disease may be rapidly lethal, tions. A careful search for concomitant infection but occasionally the patient will survive for a year is made, particularly to exclude pneumococcal copyright. or more without fatal infection or lethal azotaemia. peritonitis or low grade cellulitis. In a patient The disease pattern tends to run true within a previously treated elsewhere, evidence of steroid family. -

The Nephrotic Syndrome in Early Infancy: a Report of Three Cases* by H

Arch Dis Child: first published as 10.1136/adc.32.163.167 on 1 June 1957. Downloaded from THE NEPHROTIC SYNDROME IN EARLY INFANCY: A REPORT OF THREE CASES* BY H. McC. GILES, R. C. B. PUGH, E. M. DARMADY, FAY STRANACK and L. I. WOOLF From the Department of Paediatrics, St. Mary's Hospital, The Hospital for Sick Children, Great Ormond Street, London, and the Central Laboratory, Portsmouth (RECEIVED FOR PUBLICATION, DECEMBER 12, 1956) The nephrotic syndrome is characterized by evidence of genetic aetiology inasmuch as two of generalized oedema, hypoproteinaemia with diminu- the infants were brother and sister and both sets of tion or reversal of the albumin/globulin ratio, hyper- parents were cousins. Further points of interest lipaemia and gross albuminuria. Haematuria is not were the demonstration of anisotropic crystalline prominent; hypertension and azotaemia, except in material in alcohol-fixed tissues from all three the terminal stages, are slight and transient and infants, and the discovery on renal microdissection often do not occur at all. Recognition of this of lesions of the proximal tubule recalling those syndrome presents no difficulty but in many cases, found in Fanconi-Lignac disease (cystinosis). particularly in childhood, its cause remains obscure. Occasionally certain drugs such as troxidone or mercury, or certain diseases such as amyloidosis, Case Reports pyelonephritis, diabetes, disseminated lupus erythe- The parents of the first two patients (and the paternal copyright. matosus or renal vein thrombosis, can be in- grandparents) are first cousins. They, and a sister born criminated. In cases which develop renal failure three years before the first of her affected siblings, have and come to necropsy the lesions of glomerulo- been investigated in detail and show no sign of renal II disease. -

Blood Or Protein in the Urine: How Much of a Work up Is Needed?

Blood or Protein in the Urine: How much of a work up is needed? Diego H. Aviles, M.D. Disclosure • In the past 12 months, I have not had a significant financial interest or other relationship with the manufacturers of the products or providers of the services discussed in my presentation • This presentation will not include discussion of pharmaceuticals or devices that have not been approved by the FDA Screening Urinalysis • Since 2007, the AAP no longer recommends to perform screening urine dipstick • Testing based on risk factors might be a more effective strategy • Many practices continue to order screening urine dipsticks Outline • Hematuria – Definition – Causes – Evaluation • Proteinuria – Definition – Causes – Evaluation • Cases You are about to leave when… • 10 year old female seen for 3 day history URI symptoms and fever. Urine dipstick showed 2+ for blood and no protein. Questions? • What is the etiology for the hematuria? • What kind of evaluation should be pursued? • Is this an indication of a serious renal condition? • When to refer to a Pediatric Nephrologist? Hematuria: Definition • Dipstick > 1+ (large variability) – RBC vs. free Hgb – RBC lysis common • > 5 RBC/hpf in centrifuged urine • Can be – Microscopic – Macroscopic Hematuria: Epidemiology • Microscopic hematuria occurs 4-6% with single urine evaluation • 0.1-0.5% of school children with repeated testing • Gross hematuria occurs in 1/1300 Localization of Hematuria • Kidney – Brown or coke-colored urine – Cellular casts • Lower tract – Terminal gross hematuria – (Blood -

Urine Cytological Examination

F1000Research 2019, 8:1878 Last updated: 28 JUL 2021 RESEARCH ARTICLE Urine cytological examination: an appropriate method that can be used to detect a wide range of urinary abnormalities [version 1; peer review: 1 approved, 1 approved with reservations] Emmanuel Edwar Siddig 1-3, Nouh S. Mohamed 4-6, Eman Taha Ali7,8, Mona A. Mohamed4, Mohamed S. Muneer 9-11, Abdulla Munir6, Ali Mahmoud Mohammed Edris8,12, Eiman S. Ahmed1, Lubna S. Elnour2, Rowa Hassan 1,13 1Mycetoma Research Center, University of Khartoum, Sudan, Khartoum, 11111, Sudan 2Faculty of Medical Laboratoy Sciences, University of Khartoum, Sudan, Khartoum, 11111, Sudan 3School of Medicine, Nile University, Sudan, Khartoum, 11111, Sudan 4Department of Parasitology and Medical Entomology, Nile university, Sudan, Khartoum, 11111, Sudan 5Department of Parasitology and Medical Entomology, Sinnar University, Sinnar, Sinnar, 11111, Sudan 6National University Research Institute, National University, Sudan, Khartoum, 11111, Sudan 7Department of Histopathology and Cytology, National University, Sudan, Khartoum, 11111, Sudan 8Department of Histopathology and Cytology, University of Khartoum, Sudan, Khartoum, 11111, Sudan 9Department of Neurology, Mayo Clinic in Florida, USA, Fl, USA 10Department of Radiology, Mayo Clinic in Florida, USA, USA 11Department of Internal Medicine, University of Khartoum, Sudan, Khartoum, 11111, Sudan 12Faculty of Applied Medical Sciences, University of Bisha, Saudi Arabia, Bisha, Saudi Arabia 13Global Health and Infection Department, Brighton and Sussex Medical School, United Kingdom, UK v1 First published: 07 Nov 2019, 8:1878 Open Peer Review https://doi.org/10.12688/f1000research.20276.1 Latest published: 07 Nov 2019, 8:1878 https://doi.org/10.12688/f1000research.20276.1 Reviewer Status Invited Reviewers Abstract Background: Urine cytology is a method that can be used for the 1 2 primary detection of urothelial carcinoma, as well as other diseases related to the urinary system, including hematuria and infectious version 1 agents.