In Memoriam: Alexander Wetmore

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Spencer Fullerton Baird

PROFESSOR SPENCER FULLERTON BAIRD “NARRATIVE HISTORY” AMOUNTS TO FABULATION, THE REAL STUFF BEING MERE CHRONOLOGY “Stack of the Artist of Kouroo” Project Spencer Fullerton Baird HDT WHAT? INDEX SPENCER FULLERTON BAIRD SPENCER FULLERTON BAIRD 1784 December 27: Elihu Spencer died (Spencer Fullerton Baird would be a great-grandson). HDT WHAT? INDEX SPENCER FULLERTON BAIRD SPENCER FULLERTON BAIRD 1823 February 3, Monday: Spencer Fullerton Baird was born. Gioachino Rossini’s melodramma tragico Semiramide to words of Rossi after Voltaire was performed for the initial time, in Teatro La Fenice, Venice, with a very enthusiastic response (this was the last opera Rossini would write for Italy). NOBODY COULD GUESS WHAT WOULD HAPPEN NEXT Spencer Fullerton Baird “Stack of the Artist of Kouroo” Project HDT WHAT? INDEX SPENCER FULLERTON BAIRD SPENCER FULLERTON BAIRD 1829 June 27, Saturday: James Smithson, who had been born in Paris in 1765, died of natural causes in Genoa. When Smithson had made his will, he had been miffed at the snottiness of British nobles to whom he was related by blood: “My name shall live in the memory of man when the titles of the Northumberlands and the Percys are extinct and forgotten.”1 A minor stipulation in the will, in which he tried to leave everything to friendlier relatives, was that should his beneficiary die without issue, he wanted the estate to be used to create a “Smithsonian Institution” dedicated to “the increase and diffusion of knowledge among men,” and stipulating also that this institution should be set up in the USA, a country toward which he had never displayed the slightest interest. -

Cumulated Bibliography of Biographies of Ocean Scientists Deborah Day, Scripps Institution of Oceanography Archives Revised December 3, 2001

Cumulated Bibliography of Biographies of Ocean Scientists Deborah Day, Scripps Institution of Oceanography Archives Revised December 3, 2001. Preface This bibliography attempts to list all substantial autobiographies, biographies, festschrifts and obituaries of prominent oceanographers, marine biologists, fisheries scientists, and other scientists who worked in the marine environment published in journals and books after 1922, the publication date of Herdman’s Founders of Oceanography. The bibliography does not include newspaper obituaries, government documents, or citations to brief entries in general biographical sources. Items are listed alphabetically by author, and then chronologically by date of publication under a legend that includes the full name of the individual, his/her date of birth in European style(day, month in roman numeral, year), followed by his/her place of birth, then his date of death and place of death. Entries are in author-editor style following the Chicago Manual of Style (Chicago and London: University of Chicago Press, 14th ed., 1993). Citations are annotated to list the language if it is not obvious from the text. Annotations will also indicate if the citation includes a list of the scientist’s papers, if there is a relationship between the author of the citation and the scientist, or if the citation is written for a particular audience. This bibliography of biographies of scientists of the sea is based on Jacqueline Carpine-Lancre’s bibliography of biographies first published annually beginning with issue 4 of the History of Oceanography Newsletter (September 1992). It was supplemented by a bibliography maintained by Eric L. Mills and citations in the biographical files of the Archives of the Scripps Institution of Oceanography, UCSD. -

Biographical Memoir Carl H. Eigenmann Leonhard

NATIONAL ACADEMY OF SCIENCES OF THE UNITED STATES OF AMERICA BIOGRAPHICAL MEMOIRS VOLUME XVIII—THIRTEENTH MEMOIR BIOGRAPHICAL MEMOIR OF CARL H. EIGENMANN 1863-1927 BY LEONHARD STEJNEGER PRESENTED TO THE ACADEMY AT THE ANNUAL MEETING, 1937 CARL H. EIGENMANN * 1863-1927 BY LEON HARD STEJNEGER Carl H. Eigenmann was born on March 9, 1863, in Flehingen, a small village near Karlsruhe, Baden, Germany, the son of Philip and Margaretha (Lieb) Eigenmann. Little is known of his ancestry, but both his physical and his mental character- istics, as we know them, proclaim him a true son of his Suabian fatherland. When fourteen years old he came to Rockport, southern Indiana, with an immigrant uncle and worked his way upward through the local school. He must have applied himself diligently to the English language and the elementary disciplines as taught in those days, for two years after his arrival in America we find him entering the University of Indiana, bent on studying law. At the time of his entrance the traditional course with Latin and Greek still dominated, but in his second year in college it was modified, allowing sophomores to choose between Latin and biology for a year's work. It is significant that the year of Eigenmann's entrance was also that of Dr. David Starr Jordan's appointment as professor of natural history. The latter had already established an enviable reputa- tion as an ichthyologist, and had brought with him from Butler University several enthusiastic students, among them Charles H. Gilbert who, although only twenty years of age, was asso- ciated with him in preparing the manuscript for the "Synopsis of North American Fishes," later published as Bulletin 19 of the United States National Museum. -

The Bluefish, an Unsolved History: Spencer Fullerton Baird's Window Into Southern New England's Coastal Fisheries

Trinity College Trinity College Digital Repository Senior Theses and Projects Student Scholarship Spring 2018 The Bluefish, An Unsolved History: Spencer Fullerton Baird's Window into Southern New England's Coastal Fisheries Elenore Saunders Trinity College, Hartford Connecticut, [email protected] Weatherly Saunders Trinity College, Hartford Connecticut, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalrepository.trincoll.edu/theses Recommended Citation Saunders, Elenore and Saunders, Weatherly, "The Bluefish, An Unsolved History: Spencer Fullerton Baird's Window into Southern New England's Coastal Fisheries". Senior Theses, Trinity College, Hartford, CT 2018. Trinity College Digital Repository, https://digitalrepository.trincoll.edu/theses/687 The Bluefish, An Unsolved History: Spencer Fullerton Baird’s Window into Southern New England’s Coastal Fisheries Weatherly Saunders Trinity College History Senior Thesis Advisor: Thomas Wickman Spring, 2018 1 Table of Contents Acknowledgements..........................................................................................................................3 Introduction......................................................................................................................................4 One: The Diseased Bluefish? The Nantucket epidemic of 1763-1764 and the disappearance of the local bluefish....................20 Two: The Bloodthirsty Bluefish Baird’s unique outlook on the coastal fishery decline due to combined human and natural -

Robert Ridgway 1850-1929

NATIONAL ACADEMY OF SCIENCES OF THE UNITED STATES OF AMERICA BIOGRAPHICAL MEMOIRS VOLUME XV SECOND MEMOIR BIOGRAPHICAL MEMOIR OF ROBERT RIDGWAY 1850-1929 BY ALEXANDER WETMORE PRESENTED TO THE ACADEMY AT THE ANNUAL MEETING, 1931 ROBERT RIDGWAY 1850-1929 BY ALEXANDER WETMORE Robert Ridgway, member of the National Academy of Science, for many years Curator of Birds in the United States National Museum, was born at Mount Carmel, Illinois, on July 2, 1850. His death came on March 25, 1929, at his home in Olney, Illinois.1 The ancestry of Robert Ridgway traces back to Richard Ridg- way of Wallingford, Berkshire, England, who with his family came to America in January, 1679, as a member of William Penn's Colony, to locate at Burlington, New Jersey. In a short time he removed to Crewcorne, Falls Township, Bucks County, Pennsylvania, where he engaged in farming and cattle raising. David Ridgway, father of Robert, was born March 11, 1819, in Harrisburg, Pennsylvania. During his infancy his family re- moved for a time to Mansfield, Ohio, later, about 1840, settling near Mount Carmel, Illinois, then considered the rising city of the west through its prominence as a shipping center on the Wabash River. Little is known of the maternal ancestry of Robert Ridgway except that his mother's family emigrated from New Jersey to Mansfield, Ohio, where Robert's mother, Henrietta James Reed, was born in 1833, and then removed in 1838 to Calhoun Praifle, Wabash County, Illinois. Here David Ridgway was married on August 30, 1849. Robert Ridgway was the eldest of ten children. -

Thomas Barbour 1884-1946 by Henry B

NATIONAL ACADEMY OF SCIENCES T H O M A S B A R B OUR 1884—1946 A Biographical Memoir by H ENRY B. BIGELO W Any opinions expressed in this memoir are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the views of the National Academy of Sciences. Biographical Memoir COPYRIGHT 1952 NATIONAL ACADEMY OF SCIENCES WASHINGTON D.C. THOMAS BARBOUR 1884-1946 BY HENRY B. BIGELOW Thomas Barbour was born on Martha's Vineyard, August 19, 1884, the son of William and Adelaide (Sprague) Barbour of New York City. In 1906 he married Rosamond Pierce of Brookline, Massachusetts, and his married life was full and harmonious, but saddened by the death of his oldest daughter Martha and of his only son William. During the last two years of his life he was in failing health, following a blood clot that had developed while he was in Miami. He was at the Museum of Comparative Zoology as usual on January 4, 1946, and in happy mood at home in Boston that evening. But he was stricken later in the night with cerebral hemorrhage, and died on January 8, without regaining consciousness. He is survived by his wife; three daughters, Mrs. Mary Bigelow Kidder, Mrs. Julia Adelaide Hallowell, and Mrs. Louisa Bowditch Parker; and two brothers, Robert and Frederick K. Barbour. Barbour prepared for college under private tutors and at Brownings School in New York City. It had been planned for him to go to Princeton, but a boyhood visit to the Museum of Comparative Zoology determined him to choose Harvard, which he entered as a freshman in the autumn of 1902. -

90 Needs of Systematics in Biology, Issued by the National Academy Of

90 needs of systematics in biology, issued by the National Academy of Sciences National Research Council, Washington, D.C., sponsored by the NRC Division of Biology and Agri- culture, organized by the Society of SystematicZoology, and containing "Applied systematics" (pp. 4-12) and other remarks by the chairman (pp. 16-23, 27, 31, 32, 35, 38, 43-45, 47, 49-53). 1954. Applied systematics: The usefulness of scientific names of animals and plants. Ann. Rep., Smithsonian Institution, 1953 (Pub. 4158): 323-337. 1954. Copepoda. In PAULS. GALTSOFFet al., Gulf of Mexico, its origin, waters, and marine life. (Fishery Bull., 89), Fishery Bull. U.S. Fish Wildl. Serv., 55: 439-442. 1957. Marine Crustacea (except ostracods and copepods). In: JOELW. HEDGPETH,(ed.), Treatise on Marine Ecology and Paleoecology, 1. Geol. Soc. America, Memoir, 67: 1151-1159. 1957. A narrative of the Smithsonian-BredinCaribbean Expedition, 1956. Ann. Rep., Smithsonian Institution, 1956 (Pub. 4285): 443-460, pls. 1-8. 1959. Clarence Raymond Shoemaker; March 12, 1874 - December 28, 1958. Journ. Washington Acad. Sci., 49 (2): 64, 65. 1959. Introduction to chapter on barnacles. In: DIXY LEE RAY (ed.), Marine boring and fouling organisms: 187-189. (University of Washington Press, Seattle). 1959. Narrative of the 1958 Smithsonian-Bredin Caribbean Expedition. Ann. Rep., Smithsonian Institution, 1958 (Pub. 4366): 419-430, pls. 1-10. 1962. Comments offered at The International Conference on Taxonomic Biochemistry, Physiology, 4, 5. 1964. Washington's transit and traffic problems (mimeographed, personally distributed, and copyrighted): 1-40. 1964. Leonhard Stejneger. SystematicZoology, 13 (4): 243-249, illustr. 1965. Crustaceans: 1-204, 76 figs. -

December 1978

BULLETIN PUBLISHED QUARTERLY Vol. 29 December, 1978 No. 4 IN MEMORIAM: ALEXANDER WETMORE I I Alexander Wetmore, 92, a charter member of the Kansas Ornithological Society and a retired secretary of the Smithsonian Institution, died on 6 December 1978. He was voted an honorary life member of the KOS on April 29, 1978. Dr. Wetmore was born in North Freedom, Wisconsin. He became interested in natural history when he was growing up and by the time he was 19, he was an assistant at the University of Kansas Museum. He earned a bachelor's degree in biology from the University of Kansas in 1912 and then came to Washington as an assistant biologist in the U.S. Biological Survey, Department of Agriculture. He earned a master's degree from George Washington University in 1916 and a doctorate in 1920. Dr. Wetmore was secretary of the Smithsonian from 1945 until 1952. His association with the institution began in 1924, when he was named superintendent of the Smithsonian's National Zoological Park, and continued until long after his retirement assecretary. He continued to do research on birds and avian fossils in a laboratory at the Smithsonian until about a year before his death. On his 90th birthday, the Smithsonian published "The Collected Papers in Avian Paleontology Honoring the 90th Birthday of Alexander Wetmore." S. Dillon Ripley, the secretary of the Sniithsonian, then wrote: "Truly the incessant and intensive zeal which he has single-mindedly given to the study of birds over the years, often at very considerable personal expenditure in time and energy, will mark the career of Alexander Wetmore as one of the most memorable in the entire history of American ornithology." He was the author of numerous articles and longer works. -

Herpetology of Porto Rico

No. 129. SMITHSONIAN INSTITUTION. UNITED STATES NATIONAL MUSEUM. THE HERPETOLOGY OF PORTO RICO BY LEONHARD STEJNEGER, >/-. Division of Reptiles and Batrachians. From the Jteport of the United States National Museum for 1903, pages 549-734, with one plate. &&2S& m&gg|$* m Vore PER\^^? «f WASHINGTON: GOVERNMENT PRINTING OFFICE. I904. Report of U. S. National Museum, 1902.— Stejneger Plate 1, Anolis krugi. Drawn by miss sigrid bentzon from a sketch from life by the author. THE HERPETOLOGY OF PORTO RICO. BY LEONHAED STEJNEGER, Curator, Division of Reptiles and Batrachians. 549 TABLE OF CONTENTS. Page Introduction 553 Historical review f>56 Distribution of species occurring in Porto Rico (table) 560 Relations and origin of the Porto Rican herpetological fauna 561 Vertical distribution ' 565 Bibliography 567 Batrachians and reptiles of Porto Rico 569 Class Batrachia 569 Class Reptilia 599 Order Squamata 599 Suborder Sauria 599 Suborder Serpen tes 683 Order Chelonia 707 _ Index . 721 551 THE HERPETOLOGY OF PORTO RICO. By Leonhard Stejneger, Curator, Division of Reptiles and Batrachians. INTRODUCTION. The present account of the herpetology of Porto Rico is based primarily upon the collections recently accumulated in the United States National Museum, consisting- of about 900 specimens. Of this large amount of material nearly 350 specimens were collected by Mr. A. B. Baker, of the National Zoological Park, who accompanied the U. S. Fish Commission expedition to Porto Rico during- the early part of 1899, and the other naturalists then attached to the Fish Hawk. a About 540 specimens were secured in 1900 by Dr. C. W. Richmond and the present writer, who visited Porto Rico and Vieques from February 12 to April 19. -

Miscellaneous Manuscripts and Books, Circa 1854-1962

Miscellaneous Manuscripts and Books, circa 1854-1962 Finding aid prepared by Smithsonian Institution Archives Smithsonian Institution Archives Washington, D.C. Contact us at [email protected] Table of Contents Collection Overview ........................................................................................................ 1 Administrative Information .............................................................................................. 1 Descriptive Entry.............................................................................................................. 1 Names and Subjects ...................................................................................................... 1 Container Listing ............................................................................................................. 3 Miscellaneous Manuscripts and Books https://siarchives.si.edu/collections/siris_arc_303964 Collection Overview Repository: Smithsonian Institution Archives, Washington, D.C., [email protected] Title: Miscellaneous Manuscripts and Books Identifier: Accession T90124 Date: circa 1854-1962 Extent: 2 cu. ft. (2 record storage boxes) Creator:: Smithsonian Institution. Libraries Language: English Administrative Information Prefered Citation Smithsonian Institution Archives, Accession T90124, Smithsonian Institution, Libraries, Miscellaneous Manuscripts and Books Descriptive Entry This accession consists of miscellaneous publications, notes, drafts, maps and other related materials. Authors and correspondents include Spencer -

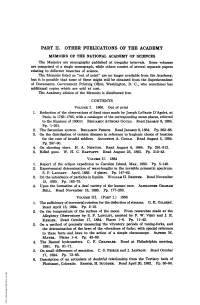

PART II. OTHER PUBLICATIONS of the ACADEMY MEMOIRS of the NATIONAL ACADEMY of SCIENCES -The Memoirs Are Monographs Published at Irregular Intervals

PART II. OTHER PUBLICATIONS OF THE ACADEMY MEMOIRS OF THE NATIONAL ACADEMY OF SCIENCES -The Memoirs are monographs published at irregular intervals. Some volumes are comprised of a single monograph, while others consist of several separate papers relating to different branches of science. The Memoirs listed as "out of print" qare no longer available from the Academy,' but it is possible that some of these might still be obtained from the Superintendent of Documents, Government Printing Office, Washington, D. C., who sometimes has additional copies which are sold at cost. The Academy edition of the Memoirs is distributed free. CONTENTS VoLums I. 1866. Out of print 1. Reduction of the observations of fixed stars made by Joseph LePaute D'Agelet, at Paris, in 1783-1785, with a catalogue of the corresponding mean places, referred to the Equinox of 1800.0. BENJAMIN APTHORP GOULD. Read January 8, 1864. Pp. 1-261. 2. The Saturnian system. BZNJAMIN Pumcu. Read January 8, 1864. Pp. 263-86. 3. On the distribution of certain diseases in reference to hygienic choice of location for the cure of invalid soldiers. AUGUSTrUS A. GouLD. Read August 5, 1864. Pp. 287-90. 4. On shooting stars. H. A. NEWTON.- Read August 6, 1864. Pp. 291-312. 5. Rifled guns. W. H. C. BARTL*rT. Read August 25, 1865. Pp. 313-43. VoLums II. 1884 1. Report of the eclipse expedition to Caroline Island, May, 1883. Pp. 5-146. 2. Experimental determination of wave-lengths in the invisible prismatic spectrum. S. P. LANGIXY. April, 1883. 4 plates. Pp. 147-2. -

The Historic “Aerodrome A”

Politically Incorrect The Flights and Fights Involving the Langley Aerodrome By Nick Engler As morning dawned on 28 May 1914, the “Aerodrome A” perched like a giant dragonfly on the edge of Lake Keuka, surrounded by journalists, photographers, even a videographer. Members of the scientific elite and Washington DC power structure were also there, among them Charles Doolittle Walcott, the Secretary of the Smithsonian Institution, and Albert Zahm, the director of the recently reopened Langley Aerodynamical Laboratory. They carefully spun the event for the media, explaining why they were attempting to fly the infamous Langley Aerodrome eleven years after two highly-publicized, unsuccessful, and nearly- catastrophic launch attempts. A cool breeze blew down the lake, gently rocking the four tandem wings that sprouted from the Aerodrome’s central framework. It was time to go. As the sun crept higher in the sky the winds would kick up. With a pronounced 12-degree dihedral between the pairs of 22-foot wings, even a modest crosswind could flip the old aircraft if it got under a wing. Workmen from the Curtiss Aeroplane and Motor Company of Hammondsport, New York lined up along the pontoons and outriggers recently added to the airframe. They lifted the half-ton aircraft a foot or so above the ramp, duck-walked it into the water and turned it into the wind. 1 Glenn Curtiss waded out, stepped onto the braces between the forward pontoons and climbed into the nacelle that hung beneath the framework. He settled into the cockpit and tested the familiar Curtiss controls – wheel, post and shoulder yoke borrowed from one of his early pushers.1 This system had replaced the dual trim wheels that had steered the original Aerodrome.