Richard Allen.P65

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Movie Aquisitions in 2010 - Hindi Cinema

Movie Aquisitions in 2010 - Hindi Cinema CISCA thanks Professor Nirmal Kumar of Sri Venkateshwara Collega and Meghnath Bhattacharya of AKHRA Ranchi for great assistance in bringing the films to Aarhus. For questions regarding these acquisitions please contact CISCA at [email protected] (Listed by title) Aamir Aandhi Directed by Rajkumar Gupta Directed by Gulzar Produced by Ronnie Screwvala Produced by J. Om Prakash, Gulzar 2008 1975 UTV Spotboy Motion Pictures Filmyug PVT Ltd. Aar Paar Chak De India Directed and produced by Guru Dutt Directed by Shimit Amin 1954 Produced by Aditya Chopra/Yash Chopra Guru Dutt Production 2007 Yash Raj Films Amar Akbar Anthony Anwar Directed and produced by Manmohan Desai Directed by Manish Jha 1977 Produced by Rajesh Singh Hirawat Jain and Company 2007 Dayal Creations Pvt. Ltd. Aparajito (The Unvanquished) Awara Directed and produced by Satyajit Raj Produced and directed by Raj Kapoor 1956 1951 Epic Productions R.K. Films Ltd. Black Bobby Directed and produced by Sanjay Leela Bhansali Directed and produced by Raj Kapoor 2005 1973 Yash Raj Films R.K. Films Ltd. Border Charulata (The Lonely Wife) Directed and produced by J.P. Dutta Directed by Satyajit Raj 1997 1964 J.P. Films RDB Productions Chaudhvin ka Chand Dev D Directed by Mohammed Sadiq Directed by Anurag Kashyap Produced by Guru Dutt Produced by UTV Spotboy, Bindass 1960 2009 Guru Dutt Production UTV Motion Pictures, UTV Spot Boy Devdas Devdas Directed and Produced by Bimal Roy Directed and produced by Sanjay Leela Bhansali 1955 2002 Bimal Roy Productions -

The Hindu, the Muslim, and the Border In

THE HINDU, THE MUSLIM, AND THE BORDER IN NATIONALIST SOUTH ASIAN CINEMA Vinay Lal University of California, Los Angeles Abstract There is but no question that we can speak about the emergence of the (usually Pakistani or Muslim) ‘terrorist’ figure in many Bollywood films, and likewise there is the indisputable fact of the rise of Hindu nationalism in the political and public sphere. Indian cinema, however, may also be viewed in the backdrop of political developments in Pakistan, where the project of Islamicization can be dated to least the late 1970s and where the turn to a Wahhabi-inspired version of Islam is unmistakable. I argue that the recent history of Pa- kistan must be seen as instigated by a disavowal of the country’s Indic self, and similarly I suggest that scholarly and popular studies of the ‘representation’ of the Muslim in “Bol- lywood” rather too easily assume that such a figure is always the product of caricature and stereotyping. But the border between Pakistan and India, between the self and the other, and the Hindu and the Muslim is rather more porous than we have imagined, and I close with hints at what it means to both retain and subvert the border. Keywords: Border, Communalism, Indian cinema, Nationalism, Pakistan, Partition, Veer-Zaara Resumen 103 Así como el personaje del ‘terrorista’ (generalmente musulmán o paquistaní) está presente en muchos filmes de Bollywood, el nacionalismo hindú está tomando la iniciativa en la esfera política del país. Sin embargo el cine indio también puede hacerse eco de acontecimientos ocurridos en Paquistán, donde desde los años Setenta se ha manifestado un proceso de islamización de la sociedad, con una indudable impronta wahabí. -

May 2013 India Review Ambassador’S PAGE America Needs More High-Skilled Worker Visas a Generous Visa Policy for Highly Skilled Workers Would Help Everyone

A Publication of the Embassy of India, Washington, D.C. May 1, 2013 I India RevieI w Vol. 9 Issue 5 www.indianembassy.org IMFC Finance Ministers and Bank Governors during a photo-op at the IMF Headquarters in Washington, D.C. on April 20. Overseas capital best protected in India — Finance Minister P. Chidambaram n India announces n scientist U.R. Rao n Pran honored incentives to boost inducted into with Dadasaheb exports Satellite Hall of Fame Phalke award Ambassador’s PAGE India is ready for U.S. natural gas There is ample evidence that the U.S. economy will benefit if LNG exports are increased he relationship between India and the United States is vibrant and growing. Near its T heart is the subject of energy — how to use and secure it in the cleanest, most efficient way possible. The India-U.S. Energy Dialogue, established in 2005, has allowed our two countries to engage on many issues. Yet as India’s energy needs con - tinue to rise and the U.S. looks to expand the marketplace for its vast cache of energy resources, our partner - ship stands to be strengthened even facilities and ports to distribute it macroeconomic scenarios, and under further. globally. every one of them the U.S. economy Despite the global economic slow - There is a significant potential for would experience a net benefit if LNG down, India’s economy has grown at a U.S. exports of LNG to grow expo - exports were increased. relatively brisk pace over the past five nentially. So far, however, while all ter - A boost in LNG exports would have years and India is now the world’s minals in the U.S. -

Filmography Dilip Kumar – the Substance and the Shadow

DILIP KUMAR: THE SUBSTANCE AND THE SHADOW Filmography Year Film Heroine Music Director 1944 Jwar Bhata Mridula Anil Biswas 1945 Pratima Swarnlata Arun Kumar 1946 Milan Meera Mishra Anil Biswas 1947 Jugnu Noor Jehan Feroz Nizami 1948 Anokha Pyar Nargis Anil Biswas 1948 Ghar Ki Izzat Mumtaz Shanti Gobindram 1948 Mela Nargis Naushad 1948 Nadiya Ke Par Kamini Kaushal C Ramchandra 1948 Shaheed Kamini Kaushal Ghulam Haider 1949 Andaz Nargis Naushad 1949 Shabnam Kamini Kaushal S D Burman 1950 Arzoo Kamini Kaushal Anil Biswas 1950 Babul Nargis Naushad 1950 Jogan Nargis Bulo C Rani 1951 Deedar Nargis Naushad 1951 Hulchul Nargis Mohd. Shafi and Sajjad Hussain 1951 Tarana Madhubala Anil Biswas 1952 Aan Nimmi and Nadira Naushad 1952 Daag Usha Kiran and Nimmi Shankar Jaikishan 1952 Sangdil Madhubala Sajjad Hussain 1953 Footpath Meena Kumari Khayyam 1953 Shikast Nalini Jaywant Shankar Jaikishan 1954 Amar Madhubala Naushad 1955 Azaad Meena Kumari C Ramchandra 1955 Insaniyat Bina Rai C Ramchandra 1955 Uran Khatola Nimmi Naushad 1955 Devdas Suchitra Sen, Vyjayanti S D Burman Mala 1957 Naya Daur Vyjayantimala O P Nayyar 1957 Musafir Usha Kiran, Suchitra Salil Chaudhury Sen 1 DILIP KUMAR: THE SUBSTANCE AND THE SHADOW 1958 Madhumati Vyjayantimala Salil Chaudhury 1958 Uahudi Meena Kumari Shankar Jaikishan 1959 Paigam Vyjayantimala, B Saroja C Ramchandra Devi 1960 Kohinoor Meena Kumari Naushad 1960 Mughal-e-Azam Madhubala Naushad 1960 Kala Bazaar (Guest Appearance) 1961 Gunga Jumna Vyjayantimala Naushad 1964 Leader Vyjayantimala Naushad 1966 Dil Diya Dara Liya -

Jio Mami Movie Mela with Star in Its 3Rd Edition Ropes in More Celebrities and More Fun…

INDIA’S ONLY MOVIE CARNIVAL IS BACK ! JIO MAMI MOVIE MELA WITH STAR IN ITS 3RD EDITION ROPES IN MORE CELEBRITIES AND MORE FUN… • How has Golmaal become the seventh highest grossing film series in Bollywood? • How do young actors, Ranbir Kapoor and Alia Bhatt keep it together in the fast and fierce world of films? • Music sensation - Vishal Shekhar share stories behind their 5 top songs Jio MAMI Movie Mela with Star will get you all the answers and more! We bring you a day filled with everything you love about the movies: Stars, Stories, Film Merchandise, Memorabilia and Finger-licking Food to go with it. Hotel Tulip Star in Juhu will host the Mela on Saturday, 7th October, 2017. Gates will open at 9:30 am. There are back-to-back sessions with your favourite magic makers that put you in the front seat and make you part of the process of making movies. Golmaal Again The first panel will see Director Rohit Shetty with the entire cast of Golmaal Again – Ajay Devgn, Arshad Warsi, Tusshar Kapoor, Shreyas Talpade, Kunal Khemu, Parineeti Chopra and Tabu, in conversation with Anupama Chopra and Rajeev Masand unveiling how the country’s biggest comedy franchise was created. One of the biggest things going for the film series has been the chemistry between the actors. The director and cast will take us behind the scenes sharing the journey that Golmaal has been. Session begins at 10:30 am Stories Behind Our Top 5 Songs Vishal–Shekhar the music composer duo Vishal Dadlani and Shekhar Ravjiani have been rocking the music world since 1999 and have given countless hits to the industry. -

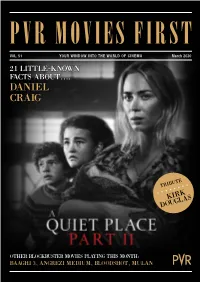

Daniel Craig

PVR MOVIES FIRST VOL. 51 YOUR WINDOW INTO THE WORLD OF CINEMA March 2020 21 LITTLE-KNOWN FACTS AboUt…. DANIEL CRAIG UTE TRIB KIRK DOUGLAS OTHER BLOCKBUSTER MOVIES PLAYING THIS MONTH: BAAGHI 3, ANGREZI MEDIUM, BLOODSHOT, MULAN GREETINGS ear Movie Lovers, 21 amazing facts about Daniel Craig, who celebrates his 52nd birthday this month. Here’s the March issue of Movies First, your exclusive window to the world of cinema. Don’t forget to take a shot at our movie quiz, too. A Quiet Place Part II sees the Abbott family locked in a creepy battle with sound-sensitive forces. Ace action We really hope you enjoy the issue. Wish you a fabulous director Rohit Shetty presents Akshay Kumar in and as month of movie watching. Sooryavanshi. Irrfan makes his much-awaited return as a Regards harried father determined to send his daughter abroad in Angrezi Medium. Join us in paying tribute to the legendary actor Kirk Gautam Dutta Douglas, the last of Hollywood’s golden greats. Learn CEO, PVR Limited USING THE MAGAZINE We hope you’ll find this magazine easy to use, but here’s a handy guide to the icons used throughout anyway. You can tap the page once at any time to access full contents at the top of the page. PLAYPLAY TRAILER BOOKSELECT TICKETS MOVIES PVR MOVIES FIRST PAGE 2 CONTENTS Tap for... Tap for... Movie OF THE MONTH UP CLOSE & PERSONAL Tap for... Tap for... MUST WATCH MASTERS@WORK Tap for... Tap for... RISING Star TRIBUTE TO BOOK TICKETS GO TO PVRCINEMAS.COM OR DOWNLOAD OUR MOBILE APP. -

Reliance Animation and Rohit Shetty Picturez's Little Singham, Launched

Media Release Reliance Animation and Rohit Shetty Picturez’s Little Singham, launched in collaboration with Discovery Kids, wins the Best Property IP Award at the India Licensing Awards 2018 Mumbai, August 31, 2018: Reliance Animation & Rohit Shetty Picturez’s Little Singham, launched in collaboration with Discovery Kids, has added another feather in its cap by winning the Best Property IP Award (Entertainment Licensing Property) at India Licensing Expo (ILE). ILE is India's first and most influential brand licensing show. The event witnessed a participation of more than 500 global and domestic companies and it was supported by LIMA (Licensing Industry Merchandisers Association). Little Singham animation series, inspired by ‘Singham’, one of Bollywood’s biggest blockbusters and mentored by ace director Rohit Shetty, is creating history across dimensions. The IP has helped in propelling ratings of Discovery Kids by more than 400% this year. ‘Little Singham’ Mobile Game added to the IP’s success hitting the top of the charts in the Arcade section by garnering 3 million downloads within the first two weeks of its launch. Speaking about the award, Tejonidhi Bhandare, COO – Reliance Animation, said, “Little Singham has created such a strong equity in less than 6 months of its launch. We are now working towards skinning this IP in the most impactful way in the future. Such appreciation makes us proud as IP owners along with all stakeholders.” Uttam Pal Singh, Head of Discovery Kids, said, “The youngest super cop Little Singham has reverberated with kids across the country making it a leading IP on air right now. -

The Ram Aur Shyam Movie in Hindi Download

The Ram Aur Shyam Movie In Hindi Download 1 / 4 The Ram Aur Shyam Movie In Hindi Download 2 / 4 3 / 4 Source : DVD. Releaser Info : MovieLoverz. Released On : 1967. Genre : Comedy, Drama, Family. Starcast : Dilip Kumar, Waheeda Rehman, Mumtaz. Size : 359 .... Download Ram Aur Shyam HDTV 1080p/720p/480p. ... Ram Aur Shyam" is a 1967 Indian Hindi feature film,The theme owes its origins to .... Ram Aur Shyam movie download Actors: Leela Mishra Kanhaiyalal Dilip ... Ram Aur Shyam 1967 Hindi Movie Watch Online | Online Watch .... movies. Ram Aur Shyam. Topics: Ram Aur Shyam. Ram Aur Shyam. Addeddate: 2013-10-28 03:06:35. Identifier: RamAurShyam. Scanner .... The Ram Aur Shyam Movie In Hindi Download >> DOWNLOAD (Mirror #1). bc8a30f7f6 Watch Ram Aur Shyam (1967) full movie HD online for .... Watch Ram Aur Shyam starring Dilip Kumar in this Drama on DIRECTV. It's available to watch.. Ram Aur Shyam (English: Ram And Shyam) is a 1967 Indian Hindi feature film, directed by Tapi Chanakya. It stars Dilip Kumar in a double role as twins .... Goldmines Hindi 10,968,964 views · 2:34:53. "Ram Aur Shyam" | Bollywood Family Drama | Dilip .... Shop online for Ram Aur Shyam (Hindi) [DVD] on Snapdeal. Get Free Shipping ... Common or Generic Name of the commodity, Bollywood Movies. No. of Items .... Ram Aur Shyam (English: Ram And Shyam) is a 1967 Indian Hindi feature film, directed by Tapi Chanakya. It stars Dilip Kumar in a double role as twins .... Delightful price reduction including Relieved outlay Ram Aur Shyam ... Direct Download Links For Hindi Movie Ram Aur Shyam MP3 Songs ... -

The Old Indian: Move by Move Free

FREE THE OLD INDIAN: MOVE BY MOVE PDF Junior Tay | 496 pages | 07 Aug 2015 | EVERYMAN CHESS | 9781781942321 | English | London, United Kingdom Old Hindi Songs Download- Old Hindi Movie, Album Songs MP3 Online Free on New customer? Create your account. Lost password? Recover password. Remembered your password? Back to login. Already have an account? Login here. Your payment information is processed securely. We do not store credit card details nor have access to your credit card information. Goods received damaged or The Old Indian: Move by Move may be returned for replacement or refund. We will refund the cost of return postage using standard first or second class post. Please contact us in advance for advice on best procedure, as in certain circumstances we are able to send our courier to collect items. You have 14 days following receipt of your order during which you may return goods. Known as a "Cooling off period". Any such returned goods must be in perfect condition including any packaging, instruction manuals etc. The cost of both the outgoing and return postage must be met by the customer. Refunds will be made within 14 days of us receiving the returned goods safely. By law sealed software products and video DVDs may not be returned once they have been opened by the customer. It is your responsibility to make sure that your operating equipment is compatible with the relevant software or video DVD before purchasing and that software purchased is functionally adequate for your needs. Please call us or email us if you have any queries in this regard. -

Pss Files Songs Acknowledgements in “Photostage

[Type(Mr) here] Soman RAGAVAN. www.somanragavan.org PSS-02. Songs acknowledgements in “Photostage” Slideshows. 2 June, 2021. Placed on website. Mauritius. SONGS ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS IN “PHOTOSTAGE” SLIDESHOWS PSS FILES ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS : ➢ Song : “Tumko Dekha To” ➢ From the film : “Saath Saath,” 1982 ➢ Singers : Jagjit Singh; Chitra Singh ➢ Director : Raman Kumar ➢ Producer : Dilip Dhawan ➢ Music : Kuldeep Singh ➢ Lyricist : ➢ Cinematography : Sunil Sharma + other rights holders + photos from the Internet ---------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- PSS-10 - SR life --Page 1 of 10 -- [Type(Mr) here] Soman RAGAVAN. www.somanragavan.org PSS-02. Songs acknowledgements in “Photostage” Slideshows. 2 June, 2021. Placed on website. Mauritius. ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS See file PSS-00. No copyright infringements intended. *Song : “Ye safar” *From the film : “1942 A Love Story,” 1994 *Singer : S. Chattopadhyay *Director : V. V. Chopra *Producer : V. V. Chopra *Music : R. D. Burman *Lyricist : J. Akthar *Cinematography : B. Pradhan + other rights holders + photos from the Internet PSS-11 www.somanragavan.org --Page 2 of 10 -- [Type(Mr) here] Soman RAGAVAN. www.somanragavan.org PSS-02. Songs acknowledgements in “Photostage” Slideshows. 2 June, 2021. Placed on website. Mauritius. ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS ➢ See file PSS-00. No copyright infringements intended. ➢ Song : “Tumko dekha to” ➢ From the film : “Hamara dil aap ke paas,” 2000 ➢ Singers : Kumar Sanu; Alka Yagnik ➢ Director : S. Kaushik ➢ Producers : S. Kapoor; B. Kapoor ➢ Music : Sanjeev-Darshan ➢ Lyricist : ➢ Cinematography : K. Lal ➢ other rights holders ➢ photos from the Internet PSS-12 www.somanragavan.org ---------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- --Page 3 of 10 -- [Type(Mr) here] Soman RAGAVAN. www.somanragavan.org PSS-02. Songs acknowledgements in “Photostage” Slideshows. 2 June, 2021. Placed on website. Mauritius. ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS See file PSS-00. No copyright infringements intended. -

Media Release 'Little Singham' Takes Discovery Kids Channel to The

Media Release ‘Little Singham’ takes Discovery Kids Channel to the second position in the kids genre Mumbai, May 8th, 2018 - Reliance Animation and Rohit Shetty Picturez (a Reliance Entertainment company) in collaboration with Discovery Kids launched its animation series ‘Little Singham’ on 21st April 2018. Inspired by ‘Singham’, India’s most successFul super cop brand and one oF the biggest Bollywood blockbusters oF all time, Little Singham targeted children in the age group of 5-11 years. The TV rating oF the channel almost doubled since the launch oF Little Singham and is continuing its spectacular rise From the 7th to the 2nd position over the last two weeks. It garnered a historic 91% growth in TV ratings over the preceding week garnering 88,952 GTVTs in week 17 as per BARC data (age group 2-14, India Urban + Rural), over week 16 data of 46,559 GTVTs taking the channel to an all time high of second position in the kids genre*. The launch of Super Hero Indian IP Little Singham helped the channel increase its reach to 24 million (a historic high For Discovery Kids). SigniFicantly, the channel also garnered 2nd highest time spends of 111 minutes per viewer in the kids genre in Week 17 as per latest BARC data* “I’m ecstatic that the kids have loved and accepted Little Singham wholeheartedly. The success oF this series has taken me a step closer to being a part oF more such special content For the kids” says ace Director, Producer & Mentor of Little Singham, Rohit Shetty. Shibasish Sarkar, COO Reliance Entertainment, added, “This animation series has set a complete new benchmark and has been immensely loved by the kids. -

Kurze Geschichte Des Indischen Films

Kurze Geschichte des indischen Films Die Frühzeit 1896-1912 Die erste Filmvorführung in Indien fand am 7. Juli des Jahres 1896 in Watson’s Hotel in Bombay statt. Der Vorführer bei dieser Premiere war kein geringerer als der Kameramann der Gebrüder Lumière, Marius Ses- tier. Die ersten regelmäßigen, täglichen Filmvorführungen begannen nur ein Jahr später, ebenfalls in Bombay, im Projektionsraum des Fotostudios Clifton & Co. Wer die schnelle Ankunft und die sich anschließende erfolgreiche Ausbreitung der neuen Technologie der bewegten Bilder im von Europa immerhin sechseinhalbtausend Kilometer entfernten indischen Subkonti- nent betrachtet, sollte die damalige britische Präsenz in diesem Teil der Welt berücksichtigen. Indien war zu dieser Zeit einer der zentralen Teile des Empires und verfügte aus diesem Grund über beste internationale Anbindungen. Der erste indische Film wurde von Harischandra S. Bhatvadekhar, gemeinhin bekannt als Save Dada, realisiert. Seinen Erstling THE WRESTLERS produzierte er 1899. Gezeigt wurde der reale Kampf zweier Ringer in den ‚Hanging Gardens‘ in Bombay. Mit dieser Zelluloidrepro- duktion eines realen Ereignisses blieb Bhatvadekhar nicht lange allein. 1900 veröffentlichte F. B. Thanawala die Filme SPLENDID NEW VIEW OF BOMBAY und TABOOT PROCESSION. Der erste zeigte einige markante An- sichten der Stadt Bombay, während der zweite eine jährlich stattfindende Muslimprozession dokumentierte. Es waren die über das Land verteilten Großstädte, in denen das neue Medium zuerst Fuß fasste. Nach Bombay waren es die Menschen in Kalkutta und Madras, die in den Genuss der laufenden Bilder kamen. Neben der dokumentarischen Präsentation realer Ereignisse waren es bald die Zusammenschnitte von Theatervorführungen, mit denen die Zu- schauer in das Dunkel der Vorführräume gelockt wurden.