Bodyline, Jardine and Masculinity

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Beware Milestones

DECIDE: How to Manage the Risk in Your Decision Making Beware milestones Having convinced you to improve your measurement of what really matters in your organisation so that you can make better decisions, I must provide a word of caution. Sometimes when we introduce new measures we actually hurt decision making. Take the effect that milestones have on people. Milestones as the name infers are solid markers of progress on a journey. You have either made the milestone or you have fallen short. There is no better example of the effect of milestones on decision making than from sport. Take the game of cricket. If you don’t know cricket all you need to focus in on is one number, 100. That number represents a century of runs by a batsman in one innings and is a massive milestone. Careers are judged on the number of centuries a batsman scores. A batsman plays the game to score runs by hitting a ball sent toward him at varying speeds of up to 100.2 miles per hour (161.3 kilometres per hour) by a bowler from 22 yards (20 metres) away. The 100.2 mph delivery, officially the fastest ball ever recorded, was delivered by Shoaib Akhtar of Pakistan. Shoaib was nicknamed the Rawalpindi Express! Needless to say, scoring runs is not dead easy. A great batting average in cricket at the highest levels is 40 plus and you are among the elite when you have an average over 50. Then there is Australia’s great Don Bradman who had an average of 99.94 with his next nearest rivals being South Africa’s Graeme Pollock with 60.97 and England’s Herb Sutcliffe with 60.63. -

Captain Cool: the MS Dhoni Story

Captain Cool The MS Dhoni Story GULU Ezekiel is one of India’s best known sports writers and authors with nearly forty years of experience in print, TV, radio and internet. He has previously been Sports Editor at Asian Age, NDTV and indya.com and is the author of over a dozen sports books on cricket, the Olympics and table tennis. Gulu has also contributed extensively to sports books published from India, England and Australia and has written for over a hundred publications worldwide since his first article was published in 1980. Based in New Delhi from 1991, in August 2001 Gulu launched GE Features, a features and syndication service which has syndicated columns by Sir Richard Hadlee and Jacques Kallis (cricket) Mahesh Bhupathi (tennis) and Ajit Pal Singh (hockey) among others. He is also a familiar face on TV where he is a guest expert on numerous Indian news channels as well as on foreign channels and radio stations. This is his first book for Westland Limited and is the fourth revised and updated edition of the book first published in September 2008 and follows the third edition released in September 2013. Website: www.guluzekiel.com Twitter: @gulu1959 First Published by Westland Publications Private Limited in 2008 61, 2nd Floor, Silverline Building, Alapakkam Main Road, Maduravoyal, Chennai 600095 Westland and the Westland logo are the trademarks of Westland Publications Private Limited, or its affiliates. Text Copyright © Gulu Ezekiel, 2008 ISBN: 9788193655641 The views and opinions expressed in this work are the author’s own and the facts are as reported by him, and the publisher is in no way liable for the same. -

AUSTRALIAN CRICKET SOCIETY 54Th Annual Report & Financial

AUSTRALIAN CRICKET SOCIETY 54th Annual Report & Financial Statements 2020~2021 to be presented at the Annual General Meeting of the Australian Cricket Society Incorporated on Friday, 20th August 2021 Australian Cricket Society Inc. Established 1967 President's Report It is my pleasure to report on another highly successful and buoyant year for the Australian Cricket Society in 2020-21. Despite all the challenges of lockdowns and the nation’s roller- coasting battle with Covid-19 we have been able to complete a dozen functions in the last 12 months, albeit the majority by ‘Zoom’, allowing us to make another substantial donation to our gold charity partners the Ponting Foundation. Among the Zoom guests were Test offspinner Ashley Mallett, authors David Frith, Dan Liebke, Craig Dodson and Wes Cusworth and leading Australian women Annabel Sutherland and Rachael Haynes. We were also pleased to hold our annual dinner, which Covid- 19 had precluded from being held in 2020. Cricket’s fraternity and friendships were never more important than in July when our dinner guest, Test fast bowler James Pattinson was in touch on the Wednesday, telling me that a personal issue precluded his attendance for the Friday. There was just 48 hours to go and Victoria’s head coach Chris Rogers stepped in. Chris Rogers demonstrating how high the Master should be raising his arm when bowling! Pic by Johann Jayasinha - SNNI The ultimate insider in Australian cricket, a champion player and an even better bloke, Chris spoke for an hour about the Vics and the Aussies and also about his memorable 2013 Ashes trip when he broke through for the first of his five Test centuries at Durham. -

Charles Kelleway Passed Away on 16 November 1944 in Lindfield, Sydney

Charle s Kelleway (188 6 - 1944) Australia n Cricketer (1910/11 - 1928/29) NS W Cricketer (1907/0 8 - 1928/29) • Born in Lismore on 25 April 1886. • Right-hand bat and right-arm fast-medium bowler. • North Coastal Cricket Zone’s first Australian capped player. He played 26 test matches, and 132 first class matches. • He was the original captain of the AIF team that played matches in England after the end of World War I. • In 26 tests he scored 1422 runs at 37.42 with three centuries and six half-centuries, and he took 52 wickets at 32.36 with a best of 5-33. • He was the first of just four Australians to score a century (114) and take five wickets in an innings (5/33) in the same test. He did this against South Africa in the Triangular Test series in England in 1912. Only Jack Gregory, Keith Miller and Richie Benaud have duplicated his feat for Australia. • He is the only player to play test cricket with both Victor Trumper and Don Bradman. • In 132 first-class matches he scored 6389 runs at 35.10 with 15 centuries and 28 half-centuries. With the ball, he took 339 wickets at 26.33 with 10 five wicket performances. Amazingly, he bowled almost half (164) of these. He bowled more than half (111) of his victims for New South Wales. • In 57 first-class matches for New South Wales he scored 3031 runs at 37.88 with 10 centuries and 11 half-centuries. He took 215 wickets at 23.90 with seven five-wicket performances, three of these being seven wicket hauls, with a best of 7-39. -

Will T20 Clean Sweep Other Formats of Cricket in Future?

Munich Personal RePEc Archive Will T20 clean sweep other formats of Cricket in future? Subhani, Muhammad Imtiaz and Hasan, Syed Akif and Osman, Ms. Amber Iqra University Research Center 2012 Online at https://mpra.ub.uni-muenchen.de/45144/ MPRA Paper No. 45144, posted 16 Mar 2013 09:41 UTC Will T20 clean sweep other formats of Cricket in future? Muhammad Imtiaz Subhani Iqra University Research Centre-IURC , Iqra University- IU, Defence View, Shaheed-e-Millat Road (Ext.) Karachi-75500, Pakistan E-mail: [email protected] Tel: (92-21) 111-264-264 (Ext. 2010); Fax: (92-21) 35894806 Amber Osman Iqra University Research Centre-IURC , Iqra University- IU, Defence View, Shaheed-e-Millat Road (Ext.) Karachi-75500, Pakistan E-mail: [email protected] Tel: (92-21) 111-264-264 (Ext. 2010); Fax: (92-21) 35894806 Syed Akif Hasan Iqra University- IU, Defence View, Shaheed-e-Millat Road (Ext.) Karachi-75500, Pakistan E-mail: [email protected] Tel: (92-21) 111-264-264 (Ext. 1513); Fax: (92-21) 35894806 Bilal Hussain Iqra University Research Centre-IURC , Iqra University- IU, Defence View, Shaheed-e-Millat Road (Ext.) Karachi-75500, Pakistan Tel: (92-21) 111-264-264 (Ext. 2010); Fax: (92-21) 35894806 Abstract Enthralling experience of the newest format of cricket coupled with the possibility of making it to the prestigious Olympic spectacle, T20 cricket will be the most important cricket format in times to come. The findings of this paper confirmed that comparatively test cricket is boring to tag along as it is spread over five days and one-days could be followed but on weekends, however, T20 cricket matches, which are normally played after working hours and school time in floodlights is more attractive for a larger audience. -

RBBA Coaches Handbook

RBBA Coaches Handbook The handbook is a reference of suggestions which provides: - Rule changes from year to year - What to emphasize that season broken into: Base Running, Batting, Catching, Fielding and Pitching By focusing on these areas coaches can build on skills from year to year. 1 Instructional – 1st and 2nd grade Batting - Timing Base Running - Listen to your coaches Catching - “Trust the equipment” - Catch the ball, throw it back Fielding - Always use two hands Pitching – fielding the position - Where to safely stand in relation to pitching machine 2 Rookies – 3rd grade Rule Changes - Pitching machine is replaced with live, player pitching - Pitch count has been added to innings count for pitcher usage (Spring 2017) o Pitch counters will be provided o See “Pitch Limits & Required Rest Periods” at end of Handbook - Maximum pitches per pitcher is 50 or 2 innings per day – whichever comes first – and 4 innings per week o Catching affects pitching. Please limit players who pitch and catch in the same game. It is good practice to avoid having a player catch after pitching. *See Catching/Pitching notations on the “Pitch Limits & Required Rest Periods” at end of Handbook. - Pitchers may not return to game after pitching at any point during that game Emphasize-Teach-Correct in the Following Areas – always continue working on skills from previous seasons Batting - Emphasize a smooth, quick level swing (bat speed) o Try to minimize hitches and inefficiencies in swings Base Running - Do not watch the batted ball and watch base coaches - Proper sliding - On batted balls “On the ground, run around. -

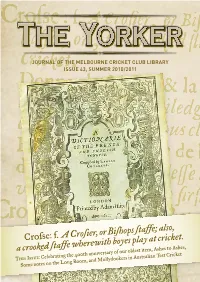

Issue 43: Summer 2010/11

Journal of the Melbourne CriCket Club library issue 43, suMMer 2010/2011 Cro∫se: f. A Cro∫ier, or Bi∫hops ∫taffe; also, a croo~ed ∫taffe wherewith boyes play at cricket. This Issue: Celebrating the 400th anniversary of our oldest item, Ashes to Ashes, Some notes on the Long Room, and Mollydookers in Australian Test Cricket Library News “How do you celebrate a Quadricentennial?” With an exhibition celebrating four centuries of cricket in print The new MCC Library visits MCC Library A range of articles in this edition of The Yorker complement • The famous Ashes obituaries published in Cricket, a weekly cataloguing From December 6, 2010 to February 4, 2010, staff in the MCC the new exhibition commemorating the 400th anniversary of record of the game , and Sporting Times in 1882 and the team has swung Library will be hosting a colleague from our reciprocal club the publication of the oldest book in the MCC Library, Randle verse pasted on to the Darnley Ashes Urn printed in into action. in London, Neil Robinson, research officer at the Marylebone Cotgrave’s Dictionarie of the French and English tongues, published Melbourne Punch in 1883. in London in 1611, the same year as the King James Bible and the This year Cricket Club’s Arts and Library Department. This visit will • The large paper edition of W.G. Grace’s book that he premiere of Shakespeare’s last solo play, The Tempest. has seen a be an important opportunity for both Neil’s professional presented to the Melbourne Cricket Club during his tour in commitment development, as he observes the weekday and event day The Dictionarie is a scarce book, but not especially rare. -

EARLY HISTORY, ANNUALS, PERIODICALS Early History, Annuals, Periodicals

EARLY HISTORY, ANNUALS, PERIODICALS Early History, Annuals, Periodicals 166. ALCOCK, C W (Compiler) 171. [ANON] The Cricket Calendar for 1888, a The Cricket Calendar for 1909 pocket diary . The Cricket Press. Original limp cloth, very The Office of “Cricket”, 1888. Original limp good. Wynyard’s copy with annotations cloth, very good. Interesting, hand-written throughout. Includes his hand-written itiner- notes by the original owner. £90 ary for the 1909/10 MCC Tour to SA. Also reports on the 1909 MCC Team to Egypt, of 167. ALCOCK, C W (Compiler) which Wynyard was a member, introduction The Cricket Calendar for 1889, a to the 1909 Australians, death of the Earl of pocket diary . Sheffield etc. (illustrated below) £80 The Office of “Cricket”, 1888. Original limp cloth, very good. Interesting, hand-written notes by the original owner. £90 168. PENTELOW, J N (Compiler) The Cricket Calendar for 1899, being a pocket diary, containing all the chief county and club fixtures of the season, arranged in chronological order etc. The Cricket Press. Original limp cloth, very good. E G Wynyard’s copy with his hand- written notes throughout and his detailed match scores and performances written in. Includes club matches, MCC, Hampshire and other first-class games. Portrait of NF Druce. 175. TROWSDALE, T B This was the only year that Pentelow edited 172. LEWIS, W J the Calendar which ran from 1869 to 1914. The Language of Cricket; with The Cricketer’s Autograph Birthday £80 illustrative extracts from the Book W Scott, 1906. 342pp, illus, contains 130 literature of the game 169. -

Bowling Performance Assessed with a Smart Cricket Ball: a Novel Way of Profiling Bowlers †

Proceedings Bowling Performance Assessed with a Smart Cricket Ball: A Novel Way of Profiling Bowlers † Franz Konstantin Fuss 1,*, Batdelger Doljin 1 and René E. D. Ferdinands 2 1 Smart Products Engineering Program, Centre for Design Innovation, Swinburne University of Technology, Melbourne 3122, Australia; [email protected] 2 Department of Exercise and Sports Science, Faculty of Health Sciences, University of Sydney, Sydney 2141, Australia; [email protected] * Correspondence: [email protected]; Tel.: +61-3-9214-6882 † Presented at the 13th conference of the International Sports Engineering Association, Online, 22–26 June 2020. Published: 15 June 2020 Abstract: Profiling of spin bowlers is currently based on the assessment of translational velocity and spin rate (angular velocity). If two spin bowlers impart the same spin rate on the ball, but bowler A generates more spin rate than bowler B, then bowler A has a higher chance to be drafted, although bowler B has the potential to achieve the same spin rate, if the losses are minimized (e.g., by optimizing the bowler’s kinematics through training). We used a smart cricket ball for determining the spin rate and torque imparted on the ball at a high sampling frequency. The ratio of peak torque to maximum spin rate times 100 was used for determining the ‘spin bowling potential’. A ratio of greater than 1 has more potential to improve the spin rate. The spin bowling potential ranged from 0.77 to 1.42. Comparatively, the bowling potential in fast bowlers ranged from 1.46 to 1.95. Keywords: cricket; smart cricket ball; profiling; performance; skill; spin rate; torque; bowling potential 1. -

Veterans' Averages Old Blues Game

VETERANS’ AVERAGES OLD BLUES GAME BATTING INNS NO RUNS AVE CTS 27th OCTOBER 1991 S. HENNESSY 4 0 187 46.75 0 OLD BLUES 8-185 (C. Tomko 68, D. Quoyle 41, P. Grimble 3-57, A. Smith 2-29) defeated J. FINDLAY 9 1 289 36.13 2 SUCC 6-181 (P. Gray 46 (ret.), W. Hayes 43 (ret.), A. Ridley 24, J. Rodgers 2-16, C. Elder P. HENNESSY 13 1 385 32.08 5c, Is 2-42). J. MACKIE 2 0 64 32.0 0 B. COLLINS 2 0 51 25.5 1 B. COOPER 5 0 123 24.6 1 Few present early, on this wind-swept Sunday, realised that they would bear witness to S. WHITTAKER 13 1 239 19.92 5 history in the making. Sure the Old Blue's victory was a touch unusual - but the sight of Roy B. NICHOLSON 13 5 141 17.63 1 Rodgers turning his leg break was stuff that historians will judge as an "event of A. SMITH 7 5 32 16.0 1 significance". C. MEARES 4 0 56 14.0 0 D. GARNSEY 19 3 215 13.44 15c,Is I. ENRIGHT 8 3 67 13.4 2 The Old Blues (or, in some cases, the Very Old Blues) produced a new squad this year. R. ALEXANDER 5 0 57 11.4 0 Whilst a steady stream of defections from the grade ranks may cause problems elsewhere for G. COONEY 7 4 34 11.33 7 the University, it is certainly ensuring that the likes of Ron Alexander are most unlikely to E. -

THE AUSTRALIAN NATIONAL FOOTBALL RECORD ------. - . --- ALAN KIPPAX SPORTS STORE 26 MARTIN PLACE -- Phone; 'Ow 8284

The May 28 .Australian National 1961 Football Record PRICE 1J. , . :.... THE -... -A.B.C. SPORTI NG SERVICE SPORTING HIGHLIGHTS . 2FC Nightly: 6.30 p.m. CHANNEL2BN . MONDAYS: SPORTS CAVALCADE : 8.30 p.m. SATURDAYS: SPORTS REVIEW 7.18 p.m. Direct Sports Telecasts every Saturday. Vol. 30. NO.7. 2 THE AUSTRALIAN NATIONAL FOOTBALL RECORD ------------------._- _._--- ALAN KIPPAX SPORTS STORE 26 MARTIN PLACE -- Phone; 'Ow 8284 SHERRIN, fAULKNER, CARNIVAL BALLS SPECIAL SHORTS, BOOTS, HOSE TRUMPS IN CLUBS Hereunder is a list of the Secretaries Newtown: Ray Judd, 10 Crystal of the various Clubs in the N.S.W. Street, Petersham. LlV[ 3U3. League. They are the people to con- North Shore; Doug Bouch, 56 tact for all your Club queries, and Lavender Street, North Sydney. any matters of interest during the XB 9020. football season (and after):- St. George: Jim Bourke, 45 Dibby Balmain: Ken Lock, 91 Day Street, Street, Kogarah Bay. Leichhardt. L~I 4981. South Sydney: Alby Dadd, 180 Bankstown: Jack Quinn, 178 Gibson Lawson Street, Redfern. Avenue, Padstow. un 7381. Sydney-Naval; Barry Goldstiver, 9 Victoria .Avenue, vVoollahra. Eastern Suburbs: Alan Little, 352 Bourke Street, Darlinghurst. FA 1810. Western Suburbs: Bill Hart, P.O. Box 21, Croydon Parle UB 5041. Liverpool: George Farrow, 13 Vir- University: Bernie Robinson, St. ginia Street, Guildford. B 0946 (Gen. Andrew's College, Sydney University. Office) . LA 1146. .•. ...•......•......• •....•.......................•...• ...•••...•...• -..._-----~-...__-..._---_ - _ _._....••.._-.- _. SOUTH'S BEST WIN FOR who boasted that incomparable back line of Kevin O'Neill, Maurie Sheahan, 26 YEARS Martin Bolger, Basil McCormack, Jac'k Murdoch and Jack Baggott-one of the toughest in all V.F.L. -

Meet... Don Bradman Ebook Free Download

MEET... DON BRADMAN PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Coral Vass | 32 pages | 01 Aug 2016 | Random House Australia | 9781925324891 | English | North Sydney, Australia Meet... Don Bradman PDF Book Teenager who killed 82yo in random, unprovoked bashing pleads for forgiveness. Federer may miss first Australian Open in more than two decades, hints at retirement Posted 3 h hours ago Mon Monday 14 Dec December at am. Straight to your inbox. And this was one of the secrets of his astonishing success with the bat. The former cricketer has taken it upon himself to study and decode Bradman's unorthodox grip and backlift. A simple looking man who introduced himself as "Don" met them at the airport. Enter your email to sign up. Treehouse Fun Book. Abhishek Mukherjee looks at the first magical moment in Indo-Australian sport relationship. Allan Ahlberg , Janet Ahlberg. You can find out more by clicking this link Close. We will have the opportunity of learning something from them. I personally look forward to emulating Sir Donald, in leaving the game in better shape for having been a part of it. No One Likes a Fart. As far as I'm concerned, he's simply the greatest sportsman the world has ever seen," he said. Each Peach Pear Plum. Book With No Pictures. Colossal Book of Colours. Books, Bauer. One can go on for pages on the legend, but this, unfortunately, is a cricket website, so let us revert to the incident in question. Now under cricketer Baheer Shah has come into the limelight for his exceptional batting average, which is even more than the legendary Sir Don Bradman.