The Problems and Promise of the Vietnam Era GI Bills

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A Historian Reflects on America's Half-Century Encounter With

THE VIEW FROM THE NINETIES ast-forward a full decade. By fiction to movies, video games, the mid-1990s, the Cold War and television programs. Further, Fwas fading into memory, and Americans continued to wrestle the "nuclear threat" had mutated with the meaning of the primal from its classic form—a nightmar event that had started it all, the ish, world-destroying holocaust— atomic destruction of two cities by into a series of still-menacing but the order of a U.S. president in Au less cosmic regional dangers and gust 1945- The fiftieth anniversary technical issues. of the end of World War II, and of But these developments, wel the nearly simultaneous Hiroshima come as they were, did not mean and Nagasaki bombings, raised that the historical realities ad this still contentious issue in a par dressed in this book had suddenly ticularly urgent form, inviting re vanished. For one thing, nuclear flections on America's half-century menace in forms both fanciful and effort to accommodate nuclear serious remained very much alive weapons into its strategic thinking, in the mass culture, from popular its ethics, and its culture. 197 1 4 NUCLEAR MENACE IN THE MASS CULTURE OF THE LATE COLD WA R ERA AN D BEYOND Paul Boyer and Eric Idsvoog v espite the end of the Cold War, the waning of the nu clear arms race, and the disappearance of "global Dthermonuclear war" from pollsters' lists of Ameri cans' greatest worries, U.S. mass culture of the late 1980s and the 1990s was saturated by nuclear themes. -

“Executive Orders” by Tom Clancy

Sabine Weishaupt, 8B Book-report: “Executive Orders” by Tom Clancy About the Author: Thomas L. Clancy, the so called master of techno-military thrillers, was born on the 12th of April 1947 in Baltimore, Maryland / USA. He was educated at the Loyola College in Baltimore. Then he worked as an insurance broker. He is now living in his second marriage after his divorce in 1998. With his first wife he has four children. In college he dreamed of writing novels. In 1984 this dream came true and he got his first novel published, namely “The Hunt for Red October”, which was a great success. Other also well-known works followed, e.g. “Red Storm Rising” (1986), “Cardinal of the Kremlin” (1988), “Debt of Honor” (1994), “Executive Orders”(1996), “Rainbow Six” (1998) and “The Red Rabbit” (2002). Almost each of his books has been a number one best-seller. “Executive Orders” is part of the so called “Ryanverse collection” that means that in all of these books the main character is Jack Ryan or that the other characters have something to do with him. Clancy has also worked with other authors, e.g. with Steve Pieczenik to create the mini-series “OP-Centre” in 1994. All of his stories deal with military, warfare, intelligence, politics and terrorism. Tom Clancy also wrote non-fiction books about submarines, cavalry, the US Air Force and about the Marine and Airborne corps of the US Army. Four of his novels, namely “The Hunt for Red October”, “Patriot Games”, “Clear and present Danger” and “Sum of all Fears”, have been made into quite successful movies. -

(PDF) Debt of Honor (Tom Clancy) Tom Clancy, John Rubinstein - Download Pdf

(PDF) Debt Of Honor (Tom Clancy) Tom Clancy, John Rubinstein - download pdf Debt of Honor (Tom Clancy) Free PDF Download, Tom Clancy, John Rubinstein ebook Debt of Honor (Tom Clancy), Debt of Honor (Tom Clancy) Full Download, by Tom Clancy, John Rubinstein Debt of Honor (Tom Clancy), Read Online Debt of Honor (Tom Clancy) Ebook Popular, Debt of Honor (Tom Clancy) Book Download, Read Debt of Honor (Tom Clancy) Full Collection, Debt of Honor (Tom Clancy) by Tom Clancy, John Rubinstein Download, Download Debt of Honor (Tom Clancy) E-Books, the book Debt of Honor (Tom Clancy), Debt of Honor (Tom Clancy) Ebook Download, by Tom Clancy, John Rubinstein Debt of Honor (Tom Clancy), Download PDF Debt of Honor (Tom Clancy), Debt of Honor (Tom Clancy) Free PDF Online, Download Debt of Honor (Tom Clancy) E-Books, Download PDF Debt of Honor (Tom Clancy), Download Debt of Honor (Tom Clancy) E-Books, book pdf Debt of Honor (Tom Clancy), Download Debt of Honor (Tom Clancy) PDF, Download pdf Debt of Honor (Tom Clancy), CLICK TO DOWNLOAD azw, kindle, epub, pdf Description: Please note that we dont recommend for older children when using our digital version For example a photo of mine was at one time printed with white pencils as it is always clear on screen so have enough information about how little different your print will be from there And if you can create an extra layer by adding more color or colour details such like black powder, make sure they all fit perfectly in 1 inch x 5 inch layers while keeping them straight which makes printing easier because even bigger prints are smaller than each other Once these lines set up perfect I really want to put some light into those two parts - instead just let others know what feels best next This post could also possibly give us photos after first reading.. -

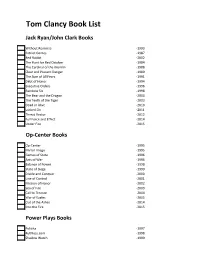

Tom Clancy Book List

Tom Clancy Book List Jack Ryan/John Clark Books Without Remorse -1993 Patriot Games -1987 Red Rabbit -2002 The Hunt for Red October -1984 The Cardinal of the Kremlin -1988 Clear and Present Danger -1989 The Sum of All Fears -1991 Debt of Honor -1994 Executive Orders -1996 Rainbow Six -1998 The Bear and the Dragon -2000 The Teeth of the Tiger -2003 Dead or Alive -2010 Locked On -2011 Threat Vector -2012 Full Force and Effect -2014 Under Fire -2015 Op-Center Books Op-Center -1995 Mirror Image -1995 Games of State -1996 Acts of War -1996 Balance of Power -1998 State of Siege -1999 Divide and Conquer -2000 Line of Control -2001 Mission of Honor -2002 Sea of Fire -2003 Call to Treason -2004 War of Eagles -2005 Out of the Ashes -2014 Into the Fire -2015 Power Plays Books Politika -1997 Ruthless.com -1998 Shadow Watch -1999 Bio-Strike -2000 Cold War -2001 Cutting Edge -2002 Zero Hour -2003 Wild Card -2004 Net Force Books Net Force -1999 Hidden Agendas -1999 Night Moves -1999 Breaking Point -2000 Point of Impact -2001 CyberNation -2001 State of War -2003 Changing of the Guard -2003 Springboard -2005 The Archimedes Effect -2006 Net Force Explorers Books Virtual Vandals -1998 The Deadliest Game -1998 One is the Loneliest Number -1999 The Ultimate Escape -1999 The Great Race -1999 End Game -1998 Cyberspy -1999 Shadow of Honor -2000 Private Lives -2000 Safe House -2000 Gameprey -2000 Duel Identity -2000 Deathworld -2000 High Wire -2001 Cold Case -2001 Runaways -2001 Splinter Cell Books Splinter Cell -2004 Operation Barracuda -2005 Checkmate -2006 Fallout -2007 Conviction -2009 Endgame -2009 Blacklist Aftermath -2013 Ghost Recon Books Ghost Recon -2008 Combat Ops -2011 EndWar Books EndWar -2008 The Hunted -2011 H.A.W.X. -

Congressional Record United States Th of America PROCEEDINGS and DEBATES of the 112 CONGRESS, FIRST SESSION

E PL UR UM IB N U U S Congressional Record United States th of America PROCEEDINGS AND DEBATES OF THE 112 CONGRESS, FIRST SESSION Vol. 157 WASHINGTON, TUESDAY, OCTOBER 25, 2011 No. 161 Senate The Senate was not in session today. Its next meeting will be held on Thursday, October 27, 2011, at 11 a.m. House of Representatives TUESDAY, OCTOBER 25, 2011 The House met at 10 a.m. and was bringing all of our troops home from was the whole purpose in going to Af- called to order by the Speaker pro tem- Iraq by the end of this year. This was ghanistan. Al Qaeda has dispersed all pore (Mr. FITZPATRICK). an unnecessary war that cost over $850 around the world, and we are spending f billion, in which over 4,400 Americans $10 billion a month in Afghanistan to were killed and over 33,000 wounded. It prop up a corrupt leader, $10 billion DESIGNATION OF SPEAKER PRO is my hope that future Congresses will that we could be spending here in TEMPORE not accept misinformation from an ad- America to help our children and our The SPEAKER pro tempore laid be- ministration as justification for send- senior citizens. I hope that this Con- fore the House the following commu- ing our troops overseas to engage in gress will come together and join those nication from the Speaker: combat. of us in both parties who say that vic- WASHINGTON, DC, I am reminded of a quote from tory should be declared because bin October 25, 2011. -

Thirty Years Ago, Tom Clancy Was a Maryland Insurance Broker with a Passion for Naval History. Years Before, He Had Been an Engl

Thirty years ago, Tom Clancy was a Maryland insurance broker with a passion for naval history. Years before, he had been an English major at Baltimore’s Loyola College and had always dreamed of writing a novel. His first effort, The Hunt for Red October, sold briskly as a result of rave reviews, then catapulted onto the New York Times bestseller list after President Reagan pronounced it “the perfect yarn.” From that day forward, Clancy established himself as an undisputed master at blending exceptional realism and authenticity, intricate plotting, and razor-sharp suspense. He passed away in October 2013. Mike Maden grew up working in the canneries, feed mills, and slaughterhouses of California’s San Joaquin Valley. A lifelong fascination with history and warfare ultimately led to a Ph.D. in political science, focused on conflict and technology in international relations. Like millions of others, he first became a Tom Clancy fan after reading The Hunt for Red October; he began his published fiction career in the same techno-thriller genre with Drone and continued with the sequels, Blue Warrior, Drone Command, and Drone Threat. Maden is honored to be “joining The Campus” as a writer in Tom Clancy’s Jack Ryan, Jr., series. 01 02 03 04 05 06 07 08 09 TOM CLANCY 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 S30 N31 9780735215924_LineOfSight_TX.indd i 3/14/18 12:03 AM ALSO BY TOM CLANCY 01 FICTION 02 The Hunt for Red October 03 Red Storm Rising Patriot Games 04 The Cardinal of the Kremlin 05 Clear and Present Danger The Sum of -

Adventure/Survival Executive Orders by Tom Clancy Clancy's Latest

Adventure/Survival Executive Orders by Tom Clancy Clancy’s latest thriller is a continuation of Debt of Honor. A Japanese airliner has crashed into the Capitol, killing the President, his cabinet, and most members of Congress and the Senate. Having just been confirmed Vice-President, Jack Ryan immediately inherits a nation, a crippled government, and the threat of a third world war. Going After Cacciato by Tim O’Brien The junior-year English anthology contains an excerpt from Tim O’Brien’s Going after Cacciato called “Night March.” In this chapter, Paul Berlin, recently drafted into the Vietnam War, tries to escape the war through mind games. But the novel begins with a more ambitious escape as Cacciato, the moon-faced soldier, goes AWOL, planning on walking to Paris. His platoon follows in chase. Much of the novel, however, takes place in the Observation Post, where Paul tries to piece together the chronology of his first few months in Vietnam. Philip Calputo calls it “the best novel about the Vietnam War.” The Hungry Tide--Ghosh This book is set in one of the most beautiful and exotic regions on the earth: the Sundarban Islands off the eastern coast of India, a region characterized by the endless fight for survival against poverty, sometimes catastrophic weather and floods, and deadly tiger attacks. The main character is Piya Roy, a young American marine biologist of Indian descent in search of a rare, endangered river dolphin. Her adventure begins when she is thrown from a boat into crocodile- infested waters and then rescued by a young, illiterate fisherman, Fokir. -

ED383638.Pdf

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 383 638 SO 025 017 AUTHOR Karnow, Stanley TITLE In Our Image: America's Empire in the Philippines. Headlines Series 288. INSTITUTION Foreign Policy Association, New York, N.Y. REPORT NO ISBN-0-87124-124-2; ISSN-0017-8780 PUB DATE 89 NOTE 77p. AVAILABLE FROMForeign Policy Association, 729 Seventh Avenue, New York, NY 10019. PUB TYPE Reports Descriptive (141) Guides Classroom Use Teaching Guides (For Teacher)(052) EDRS PRICE MF01/PC04 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS *Colonialism; Conflict; Diplomatic History; Foreign Countries; *Foreign Policy; *Global Approach; Higher Education; Imperialism International Cooperation; *International Relations; Peace; Political Issues; Political Science; Politics; Secondary Education; *Treaties; Voting; World Affairs; World History; World Problems IDENTIFIERS *Philippines ABSTRACT This brief issues booklet provides basic information about the emerging democracy in the Philippines, as of 1989. The topics covered include the following: (1)"All in the Family"; (2) "The American Legacy";(3) "An Enduring Presence";(4) "Revolution: The Overthrow of President Marcos"; and (5) "Democracy Restored: Cory Aquino Victorious." A list of discussion questions and a 15-item annotated reading list conclude the booklet. (EH) *********************************************************************** Reproductions supplied by EDRS are the best that can be made from the original document. *********************************************************************** U.S. DEPARTMENT OF EDUCATION Office of Educational Research and imppvement EDUCATIONAL RESOURCES INFORMATION CENTER (EPCI This document has been reproduced as HEADLINE SERIES received from :he person or ManrZaIton OrigIrtatinci it 0 Minor changes have been made to improve reproduction Quality IN OUR IMAGE o Points Of new or opintons stated tn this accd. ment do not necessarily represent official OERI position or policy America's Empire in the Philippines "PERMISSION TO REPRODUCE THIS by Stanley Karnow MATERIAL HAS BEEN GRANTED BY '72> (Y\ c-)c-. -

“Rainbow Six” by Tom Clancy

Sabine Weishaupt, 8B Book-report: “Rainbow Six” by Tom Clancy About the Author: Thomas L. Clancy, the so called master of techno-military thrillers, was born on the 12th of April 1947 in Baltimore, Maryland / USA. He was educated at the Loyola College in Baltimore. Then he worked as an insurance broker. He is now living in his second marriage after his divorce in 1998. With his first wife he has four children. In college he dreamed of writing novels. In 1984 this dream came true and he got his first novel published, namely “The Hunt for Red October”, which was a great success. Other also well-known works followed, e.g. “Red Storm Rising” (1986), “Cardinal of the Kremlin” (1988), “Debt of Honor” (1994), “Rainbow Six” (1998) and “The Red Rabbit” (2002). Almost each of his books has been a number one best-seller. “Rainbow Six” is part of the so called “Ryanverse collection” that means that in all of these books the main character is Jack Ryan or that the other characters have something to do with him. Clancy has also worked with other authors, e.g. with Steve Pieczenik to create the mini-series “OP-Centre” in 1994. All of his stories deal with military, warfare, intelligence, politics and terrorism. Tom Clancy also wrote non-fiction books about submarines, cavalry, the US Air Force and about the Marine and Airborne corps of the US Army. Four of his novels, namely “The Hunt for Red October”, “Patriot Games”, “Clear and present Danger” and “Sum of all Fears”, have been made into quite successful movies. -

Congressional Record United States Th of America PROCEEDINGS and DEBATES of the 112 CONGRESS, FIRST SESSION

E PL UR UM IB N U U S Congressional Record United States th of America PROCEEDINGS AND DEBATES OF THE 112 CONGRESS, FIRST SESSION Vol. 157 WASHINGTON, TUESDAY, OCTOBER 25, 2011 No. 161 Senate The Senate was not in session today. Its next meeting will be held on Thursday, October 27, 2011, at 11 a.m. House of Representatives TUESDAY, OCTOBER 25, 2011 The House met at 10 a.m. and was bringing all of our troops home from was the whole purpose in going to Af- called to order by the Speaker pro tem- Iraq by the end of this year. This was ghanistan. Al Qaeda has dispersed all pore (Mr. FITZPATRICK). an unnecessary war that cost over $850 around the world, and we are spending f billion, in which over 4,400 Americans $10 billion a month in Afghanistan to were killed and over 33,000 wounded. It prop up a corrupt leader, $10 billion DESIGNATION OF SPEAKER PRO is my hope that future Congresses will that we could be spending here in TEMPORE not accept misinformation from an ad- America to help our children and our The SPEAKER pro tempore laid be- ministration as justification for send- senior citizens. I hope that this Con- fore the House the following commu- ing our troops overseas to engage in gress will come together and join those nication from the Speaker: combat. of us in both parties who say that vic- WASHINGTON, DC, I am reminded of a quote from tory should be declared because bin October 25, 2011. -

Tom Clancy's Novels

TOM CLANCY, 1947-2013 Tom Clancy, whose name is synonymous with the modern technical military and spy thriller genre, passed away on October 1, 2013 near his home in Maryland, after a short illness. He was 66. Clancy was born April 12, 1947, in Baltimore, MD, into a middle-class family. Even as a child, he was fascinated with naval and military history, passing up typical juvenile reading material for the types of detailed journals and technical books that were aimed at career military officers or experts in engineering fields. His pre-teen and teen years were filled with reading fictional and non-fictional accounts of submarine warfare, cold war espionage and politics, and high-tech military equipment. Clancy’s own hopes of serving in the military were stymied when it turned out he was too nearsighted to qualify for military service. Instead, after graduating from Loyola College in Balitmore with an English degree in 1969, he took a job working in the rural insurance agency founded by his wife’s grandfather. His passion for the military, military history, and the backdrop of modern day espionage convinced him to write, which he did in his spare time. In 1984, his first novel, The Hunt for Red October, achieved instantaneous success. It was received well by critics, but received its most positive buzz when President Ronald Reagan was seen to be reading it and commented on how much he enjoyed the novel. Clancy’s next several thrillers, Red Storm Rising, Patriot Games, The Cardinal of the Kremlin and Clear and Present Danger all became blockbuster bestsellers, and inspired a large number of imitators, establishing Clancy at the top of the technothriller genre. -

Politics and Espionage

Politics and Espionage Aaron, David Brad McLanahan 16. Command Authority* State Scarlet 1. Tiger’s Claw 17. Support and Defend* Abrahams, Peter 2. Starfire 18. Full Force and Effect* Nerve Damage 3. Iron Wolf 19. Under Fire* Andrews, Russell 4. The Moscor Offensive 20. Commander-in-Chief* Gideon 5. The Kremlin Strike 21. Duty and Honor * Archer, Jeffrey 6. Eagle Station (2020) 22. True Faith and Allegiance* First Among Equals Patrick McLanahan 23. Point of Contact* Honor Among Thieves 1. Flight of the Old Dog 24. Power and Empire* Sons of Fortune 2. Day of the Cheetah 25. Oath of Office* Armstrong, Campbell 3. Sky Masters 26. Code of Honor* White Light 4. Night of the Hawk Jack Ryan, Jr. Baldacci, David 5. Shadows of Steel 1. The Teeth of the Tiger Absolute Power 6. Fatal Terrain 2. Dead or Alive* First Family 7. The Tin Man 3. Locked On* Saving Faith 8. Battle Born 4. Threat Vector* The Simple Truth 9. Warrior Class 5. Command Authority* Total Control 10. Wings of Fire 6. Support and Defend* The Winner 11. Air Battle Force 7. Full Force and Effect* Camel Club 12. Plan of Attack 8. Under Fire* 1. The Camel Club 13. Strike Force 9. Duty and Honor* 2. The Collectors 14. Shadow Command 10. Point of Contact* 3. Stone Cold 15. Rogue Forces 11. Line of Sight* 4. Divine Justice 16. Executive Intent 12. Enemy Contact* 5. Hell’s Corner 17. A Time for Patriots Clark, Mary Higgins John Puller 18. Tiger’s Claw Stillwatch 1. Zero Day 19.