Report Case Study 25

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Rembrandt Van Rijn

Rembrandt van Rijn 1606-1669 REMBRANDT HARMENSZ. VAN RIJN, born 15 July er (1608-1651), Govaert Flinck (1615-1660), and 1606 in Leiden, was the son of a miller, Harmen Ferdinand Bol (1616-1680), worked during these Gerritsz. van Rijn (1568-1630), and his wife years at Van Uylenburgh's studio under Rem Neeltgen van Zuytbrouck (1568-1640). The brandt's guidance. youngest son of at least ten children, Rembrandt In 1633 Rembrandt became engaged to Van was not expected to carry on his father's business. Uylenburgh's niece Saskia (1612-1642), daughter Since the family was prosperous enough, they sent of a wealthy and prominent Frisian family. They him to the Leiden Latin School, where he remained married the following year. In 1639, at the height of for seven years. In 1620 he enrolled briefly at the his success, Rembrandt purchased a large house on University of Leiden, perhaps to study theology. the Sint-Anthonisbreestraat in Amsterdam for a Orlers, Rembrandt's first biographer, related that considerable amount of money. To acquire the because "by nature he was moved toward the art of house, however, he had to borrow heavily, creating a painting and drawing," he left the university to study debt that would eventually figure in his financial the fundamentals of painting with the Leiden artist problems of the mid-1650s. Rembrandt and Saskia Jacob Isaacsz. van Swanenburgh (1571 -1638). After had four children, but only Titus, born in 1641, three years with this master, Rembrandt left in 1624 survived infancy. After a long illness Saskia died in for Amsterdam, where he studied for six months 1642, the very year Rembrandt painted The Night under Pieter Lastman (1583-1633), the most impor Watch (Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam). -

Gary Schwartz

Gary Schwartz A Corpus of Rembrandt Paintings as a Test Case for Connoisseurship Seldom has an exercise in connoisseurship had more going for it than the world-famous Rembrandt Research Project, the RRP. This group of connoisseurs set out in 1968 to establish a corpus of Rembrandt paintings in which doubt concer- ning attributions to the master was to be reduced to a minimum. In the present enquiry, I examine the main lessons that can be learned about connoisseurship in general from the first three volumes of the project. My remarks are limited to two central issues: the methodology of the RRP and its concept of authorship. Concerning methodology,I arrive at the conclusion that the persistent appli- cation of classical connoisseurship by the RRP, attended by a look at scientific examination techniques, shows that connoisseurship, while opening our eyes to some features of a work of art, closes them to others, at the risk of generating false impressions and incorrect judgments.As for the concept of authorship, I will show that the early RRP entertained an anachronistic and fatally puristic notion of what constitutes authorship in a Dutch painting of the seventeenth century,which skewed nearly all of its attributions. These negative judgments could lead one to blame the RRP for doing an inferior job. But they can also be read in another way. If the members of the RRP were no worse than other connoisseurs, then the failure of their enterprise shows that connoisseurship was unable to deliver the advertised goods. I subscribe to the latter conviction. This paper therefore ends with a proposal for the enrichment of Rembrandt studies after the age of connoisseurship. -

The Leiden Collection Catalogue, 2Nd Ed

Rembrandt van Rijn (Leiden 1606 – 1669 Amsterdam) How to cite Bakker, Piet. “Rembrandt van Rijn” (2017). In The Leiden Collection Catalogue, 2nd ed. Edited by Arthur K. Wheelock Jr. New York, 2017–20. https://theleidencollection.com/artists/rembrandt-van-rijn/ (archived June 2020). A PDF of every version of this biography is available in this Online Catalogue's Archive, and the Archive is managed by a permanent URL. New versions are added only when a substantive change to the narrative occurs. According to Rembrandt’s first biographer, Jan Jansz. Orlers (1570–1646), the most famous Dutch painter of the seventeenth century was born in Leiden on 15 July 1606, the ninth child of the miller Harmen Gerritsz van Rijn (1568–1630) and the baker’s daughter Neeltje Willemsdr van Suydtbrouck (ca. 1568–1640).[1] The painter grew up in the Weddesteeg, across from his father’s mill. He attended the Latin school in Leiden, and his parents enrolled him in the University of Leiden when he was fourteen, “so that upon reaching adulthood he could use his knowledge for the service of his city and the benefit of the community at large.”[2] This, however, did not come to pass, for Rembrandt’s ambitions lay elsewhere, “his natural inclination being for painting and drawing only.”[3] His parents took him out of school in 1621, allowing him to follow his passion. They apprenticed him to Jacob Isaacsz van Swanenburgh (1571–1638), who had just returned from Italy, “with whom he stayed for about three years.”[4] It is during this time that Rembrandt probably painted his earliest known works: Stone Operation (Allegory of Touch), Three Musicians (Allegory of Hearing), and Unconscious Patient (Allegory of Smell).[5] Rembrandt moved to Amsterdam in 1625 to complete his training with the leading painter of his day, Pieter Lastman (1583–1633), with whom, according to Arnold Houbraken, he stayed for six months.”[6] When Rembrandt returned to Leiden, he set up his own workshop in his parents’ house. -

The Wallace Collection — Rubens Reuniting the Great Landscapes

XT H E W ALLACE COLLECTION RUBENS: REUNITING THE GREAT LANDSCAPES • Rubens’s two great landscape paintings reunited for the first time in 200 years • First chance to see the National Gallery painting after extensive conservation work • Major collaboration between the National Gallery and the Wallace Collection 3 June - 15 August 2021 #ReunitingRubens In partnership with VISITFLANDERS This year, the Wallace Collection will reunite two great masterpieces of Rubens’s late landscape painting: A View of Het Steen in the Early Morning and The Rainbow Landscape. Thanks to an exceptional loan from the National Gallery, this is the first time in two hundred years that these works, long considered to be companion pieces, will be seen together. This m ajor collaboration between the Wallace Collection and the National Gallery was initiated with the Wallace Collection’s inaugural loan in 2019 of Titian’s Perseus and Andromeda, enabling the National Gallery to complete Titian’s Poesie cycle for the first time in 400 years for their exhibition Titian: Love, Desire, Death. The National Gallery is now making an equally unprecedented reciprocal loan to the Wallace Collection, lending this work for the first time, which will reunite Rubens’s famous and very rare companion pair of landscape paintings for the first time in 200 years. This exhibition is also the first opportunity for audiences to see the National Gallery painting newly cleaned and conserved, as throughout 2020 it has been the focus of a major conservation project specifically in preparation for this reunion. The pendant pair can be admired in new historically appropriate, matching frames, also created especially for this exhibition. -

Rembrandt in Southern California Exhibition Guide

An online exhibition exploring paintings by Rembrandt in Southern California. A collaboration between The Exhibition Rembrandt in Southern California is a virtual exhibition of paintings by Rembrandt Harmensz. van Rijn (Dutch, 1606–1669) on view in Southern California museums. This collaborative presentation offers a unique guide to exploring these significant holdings and provides information, suggested connections, and points of comparison for each work. Southern California is home to the third-largest assemblage of Rembrandt paintings in the United States, with notable strength in works from the artist’s dynamic early career in Leiden and Amsterdam. Beginning with J. Paul Getty’s enthusiastic 1938 purchase of Portrait of Marten Looten (given to LACMA in 1953; no. 9 in the Virtual Exhibition), the paintings have been collected over 80 years and are today housed in five museums, four of which were forged from private collections: the Hammer Museum, the J. Paul Getty Museum, and the Los Angeles County Museum of Art (LACMA) in Los Angeles; the Norton Simon Museum in Pasadena; and the Timken Museum of Art in San Diego. In addition, Rembrandt in Southern California provides insight into the rich holdings of etchings and drawings on paper by the master in museums throughout the region. Together, Southern California’s drawn, etched and painted works attest to the remarkable range of Rembrandt’s achievement across his long career. Self-Portrait (detail), about 1636–38. Oil on panel, 24 7/8 x 19 7/8 in. (63.2 x 50.5 cm). The Norton Simon Foundation, Pasadena, F.1969.18.P 1 NO. -

Rembrandt Self Portraits

Rembrandt Self Portraits Born to a family of millers in Leiden, Rembrandt left university at 14 to pursue a career as an artist. The decision turned out to be a good one since after serving his apprenticeship in Amsterdam he was singled out by Constantijn Huygens, the most influential patron in Holland. In 1634 he married Saskia van Uylenburgh. In 1649, following Saskia's death from tuberculosis, Hendrickje Stoffels entered Rembrandt's household and six years later they had a son. Rembrandt's success in his early years was as a portrait painter to the rich denizens of Amsterdam at a time when the city was being transformed from a small nondescript port into the The Night Watch 1642 economic capital of the world. His Rembrandt painted the large painting The Militia Company of Captain Frans Banning Cocq historical and religious paintings also between 1640 and 1642. This picture was called De Nachtwacht by the Dutch and The gave him wide acclaim. Night Watch by Sir Joshua Reynolds because by the 18th century the picture was so dimmed and defaced that it was almost indistinguishable, and it looked quite like a night scene. After it Despite being known as a portrait painter was cleaned, it was discovered to represent broad day—a party of musketeers stepping from a Rembrandt used his talent to push the gloomy courtyard into the blinding sunlight. boundaries of painting. This direction made him unpopular in the later years of The piece was commissioned for the new hall of the Kloveniersdoelen, the musketeer branch of his career as he shifted from being the the civic militia. -

Evolution and Ambition in the Career of Jan Lievens (1607-1674)

ABSTRACT Title: EVOLUTION AND AMBITION IN THE CAREER OF JAN LIEVENS (1607-1674) Lloyd DeWitt, Ph.D., 2006 Directed By: Prof. Arthur K. Wheelock, Jr. Department of Art History and Archaeology The Dutch artist Jan Lievens (1607-1674) was viewed by his contemporaries as one of the most important artists of his age. Ambitious and self-confident, Lievens assimilated leading trends from Haarlem, Utrecht and Antwerp into a bold and monumental style that he refined during the late 1620s through close artistic interaction with Rembrandt van Rijn in Leiden, climaxing in a competition for a court commission. Lievens’s early Job on the Dung Heap and Raising of Lazarus demonstrate his careful adaptation of style and iconography to both theological and political conditions of his time. This much-discussed phase of Lievens’s life came to an end in 1631when Rembrandt left Leiden. Around 1631-1632 Lievens was transformed by his encounter with Anthony van Dyck, and his ambition to be a court artist led him to follow Van Dyck to London in the spring of 1632. His output of independent works in London was modest and entirely connected to Van Dyck and the English court, thus Lievens almost certainly worked in Van Dyck’s studio. In 1635, Lievens moved to Antwerp and returned to history painting, executing commissions for the Jesuits, and he also broadened his artistic vocabulary by mastering woodcut prints and landscape paintings. After a short and successful stay in Leiden in 1639, Lievens moved to Amsterdam permanently in 1644, and from 1648 until the end of his career was engaged in a string of important and prestigious civic and princely commissions in which he continued to demonstrate his aptitude for adapting to and assimilating the most current style of his day to his own somber monumentality. -

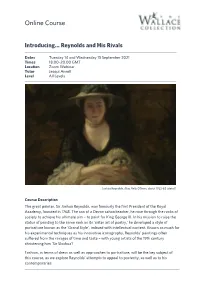

Online Course Description

Online Course Introducing… Reynolds and His Rivals Dates Tuesday 14 and Wednesday 15 September 2021 Times 18.00–20.00 GMT Location Zoom Webinar Tutor Jacqui Ansell Level All Levels Joshua Reynolds, Miss Nelly O'Brien, about 1762-63 (detail) Course Description The great painter, Sir Joshua Reynolds, was famously the first President of the Royal Academy, founded in 1768. The son of a Devon schoolteacher, he rose through the ranks of society to achieve his ultimate aim – to paint for King George III. In his mission to raise the status of painting to the same rank as its ‘sister art of poetry,’ he developed a style of portraiture known as the ‘Grand Style’, imbued with intellectual content. Known as much for his experimental techniques as his innovative iconography, Reynolds’ paintings often suffered from the ravages of time and taste – with young artists of the 19th century christening him ‘Sir Sloshua’! Fashion, in terms of dress as well as approaches to portraiture, will be the key subject of this course, as we explore Reynolds’ attempts to appeal to posterity, as well as to his contemporaries. Session One: ‘Something Modern for the Sake of Likeness’ The 18th century was a ‘Golden Age’ for British portraiture, with Hogarth, Reynolds, Ramsay, as well as Wright of Derby, Gainsborough and Lawrence emerging to lead this field. The rise of Rococo fashions in art and dress created a concern for frills and fripperies, which posed a problem for artists. Not only were these fiddly and time- consuming to consign to canvas, but the rapid pace of fashion change meant that portraits could look old-fashioned before the paint was dry. -

DCMS-Sponsored Museums and Galleries Annual Performance

Correction notice: The chart showing the Total number of visits to DCMS - sponsored museums and galleries, 2002/03 to 2018/19 and Figure 2 showing the Total number of visits to the DCMS- sponsored museums and galleries, 2008/09 to 2018/19 were updated on 27 January 2020 to reflect the minor amendments made to the Tyne and Wear visitor figures for the years 2008/09 to 2014/15. This release covers the annual DCMS-Sponsored Museums performance indicators for DCMS- sponsored museums and galleries and Galleries Annual in 2018/19. The DCMS-sponsored museums Performance Indicators and galleries are: British Museum 2018/19 Geffrye Museum Horniman Museum Total number of visits to DCMS-sponsored museums and Imperial War Museums galleries, 2008/09 to 2018/19 National Gallery National Museums Liverpool National Portrait Gallery Natural History Museum Royal Armouries Royal Museums Greenwich Science Museum Group Sir John Soane’s Museum Tate Gallery Group Victoria and Albert Museum The Wallace Collection Responsible statistician: Wilmah Deda 020 7211 2376 Statistical enquiries: In 2018/19 there were 49.8 million visits to DCMS- [email protected] sponsored museums and galleries, an increase of @DCMSInsight 48.0% from 33.6 million visits in 2002/03 when records began. Media enquiries: 020 7211 2210 Of these1: Date: 24 October 2019 Contents 1: Introduction……………………..2 2: Visits to DCMS-sponsored museums and galleries………......3 3: Regional engagement...............9 4: Self-generated income……….10 were made by were made by Annex A: Background …...……..12 children under the overseas age of 16 visitors The total self-generated income for DCMS-sponsored museums and galleries was £289 million, an increase of 5.0% from £275 million in 2017/182. -

The Drawings of Cornelis Visscher (1628/9-1658) John Charleton

The Drawings of Cornelis Visscher (1628/9-1658) John Charleton Hawley III Jamaica Plain, MA M.A., History of Art, Institute of Fine Arts – New York University, 2010 B.A., Art History and History, College of William and Mary, 2008 A Dissertation presented to the Graduate Faculty of the University of Virginia in Candidacy for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy Department of Art and Architectural History University of Virginia May, 2015 _______________________________________ _______________________________________ _______________________________________ _______________________________________ Table of Contents Abstract ............................................................................................................................................. i Acknowledgements.......................................................................................................................... ii Introduction ..................................................................................................................................... 1 Chapter 1: The Life of Cornelis Visscher .......................................................................................... 3 Early Life and Family .................................................................................................................... 4 Artistic Training and Guild Membership ...................................................................................... 9 Move to Amsterdam ................................................................................................................. -

Rembrandt Remembers – 80 Years of Small Town Life

Rembrandt School Song Purple and white, we’re fighting for you, We’ll fight for all things that you can do, Basketball, baseball, any old game, We’ll stand beside you just the same, And when our colors go by We’ll shout for you, Rembrandt High And we'll stand and cheer and shout We’re loyal to Rembrandt High, Rah! Rah! Rah! School colors: Purple and White Nickname: Raiders and Raiderettes Rembrandt Remembers: 80 Years of Small-Town Life Compiled and Edited by Helene Ducas Viall and Betty Foval Hoskins Des Moines, Iowa and Harrisonburg, Virginia Copyright © 2002 by Helene Ducas Viall and Betty Foval Hoskins All rights reserved. iii Table of Contents I. Introduction . v Notes on Editing . vi Acknowledgements . vi II. Graduates 1920s: Clifford Green (p. 1), Hilda Hegna Odor (p. 2), Catherine Grigsby Kestel (p. 4), Genevieve Rystad Boese (p. 5), Waldo Pingel (p. 6) 1930s: Orva Kaasa Goodman (p. 8), Alvin Mosbo (p. 9), Marjorie Whitaker Pritchard (p. 11), Nancy Bork Lind (p. 12), Rosella Kidman Avansino (p. 13), Clayton Olson (p. 14), Agnes Rystad Enderson (p. 16), Alice Haroldson Halverson (p. 16), Evelyn Junkermeier Benna (p. 18), Edith Grodahl Bates (p. 24), Agnes Lerud Peteler (p. 26), Arlene Burwell Cannoy (p. 28 ), Catherine Pingel Sokol (p. 29), Loren Green (p. 30), Phyllis Johnson Gring (p. 34), Ken Hadenfeldt (p. 35), Lloyd Pressel (p. 38), Harry Edwall (p. 40), Lois Ann Johnson Mathison (p. 42), Marv Erichsen (p. 43), Ruth Hill Shankel (p. 45), Wes Wallace (p. 46) 1940s: Clement Kevane (p. 48), Delores Lady Risvold (p. -

ARTIST Is in Caps and Min of 6 Spaces from the Top to Fit in Before Heading

FRANS VAN MIERIS the Elder (1635 – Leiden – 1681) A Self-portrait of the Artist, bust-length, wearing a Turban crowned with a Feather, and a fur- trimmed Robe On panel, oval, 4½ x 3½ ins. (11 x 8.2 cm) Provenance: Jan van Beuningen, Amsterdam From whom purchased by Pieter de la Court van der Voort (1664-1739), Amsterdam, before 1731, for 120 Florins (“door myn vaader gekofft van Jan van Beuningen tot Amsterdam”) In Pieter de la Court van der Voort’s inventory of 1731i His son Allard de la Court van der Voort, and in his inventories of 1739ii and 1749iii His widow, Catherine de la Court van de Voort-Backer Her deceased sale, Leiden, Sam. and Joh. Luchtmans, 8 September 1766, lot 23, for 470 Florins to De Winter Gottfried Winkler, Leipzig, by 1768 Probably anonymous sale, “Twee voornamen Liefhebbers” (two distinguished amateurs), Leiden, Delfos, 26 August 1788, lot 85, (as on copper), sold for f. 65.5 to Van de Vinne M. Duval, St. Petersburg (?) and Geneva, by 1812 His sale, London, Phillips, 12 May 1846, lot 42 (as a self-portrait of the artist), sold for £525 Anonymous sale, London, Christie’s, 21 February 1903, lot 80, (as a self-portrait of the artist) Max and Fanny Steinthal, Charlottenburg, Berlin, by 1909, probably acquired in 1903 Thence by descent to the previous owner, Private Collection Belgium, 2012 Exhibited: Berlin, Köningliche Kunstakademie, Illustrierter Katalog der Ausstellung von Bildnissen des fünfzehnten bis achtzehnten Jahrhunderts aus dem Privatbesitz der Mitglieder des Vereins, 31 March – 30 April 1909, cat.