Bertel Thorvaldsen, Christus (Christ)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

56.4Holzapfelmasterslight.Pdf

Herman du Toit. Masters of Light: Coming unto Christ through Inspired Devotional Art. Springville, Utah: Cedar Fort, 2016. Reviewed by Richard Neitzel Holzapfel BOOK REVIEWS erman du Toit is the former head of audience education and Hresearch at the BYU Museum of Art (MOA). A gifted and talented art educator, curator, critic, and author, du Toit caps his long career of considering, thinking, teaching, and writing about the power of reli- gious art with a beautifully written and illustrated volume, Masters of Light. As Richard Oman, a well-known LDS art historian, states in the fore- word, “Most of us strive for a closer relationship with Christ. Among frequently used external aids are written and spoken words in inspira- tional talks, sermons, and books. In this book, Herman du Toit helps us better understand and use an additional source: inspired visual art” (x). The book highlights the work of four influential nineteenth-century Protestant European artists—Bertel Thorvaldsen, Carl Bloch, Heinrich Hofmann, and Frans Schwartz—who have captured the imagination of Latter-day Saint audiences for the last half century. However, the book is much more than the story of four artists and the devotional art they produced during their careers. Du Toit carefully crafts word pictures equally as beautiful as the art he uses to illustrate the book. The result is a theological discussion of the centrality of Jesus Christ in the lives of believers. Du Toit ties this fundamental core doc- trine of the restored Church to the art the Church uses to proclaim Christ to the world. -

Portrætter I Ord Portraits in Words ~

PORTRÆTTER I ORD ~ PORTRAITS IN WORDS MERETE PRYDS HELLE INTRODUKTION INTRODUCTION Det kan være svært at finde ind bag Finding a way behind the white mar- den hvide marmorhud og frem til ble skin can be difficult, to reach the de mennesker, der i 1800-tallet stod people who, during the nineteenth model til Thorvaldsens skulpturelle century, modelled for Thorvaldsen’s portrætter. Merete Pryds Helle har sculptural portraits. Merete Pryds givet marmormenneskene nyt liv og Helle has breathed new life into the- lader os i 30 små fiktionsbiografier se marble people, and through thirty møde personer, der engang elskede, short fictional biographies, invites sørgede, dansede, slikkede tæer og us to meet people who once loved, huggede i sten. mourned, danced, licked toes and Fantasi og frie associationer får sculpted stone. lov til at blande sig med biografiske In these texts, imagination and læsninger i teksterne, som er blevet til free association are allowed to mingle i åbne skriveværksteder, hvor Pryds with biographical study, which have Helle har inviteret museets besøgende come to life during open writers’ til, sammen med hende, at digte nye workshops, where Pryds Helle has livsfortællinger til portrætterne. invited the museum’s visitors to help Fiktionsbiografierne er skrevet her compose new life stories for the til udstillingen Ansigt til Ansigt. Thor- portraits. valdsen og Portrættet. De 10 værker, The fictional biographies have som danner udgangspunkt for de 30 been written for the exhibition Face to tekster, er markeret med lyserøde sil- Face. Thorvaldsen and Portraiture. These kebånd i udstillingsperioden. ten works, which form the starting point for the thirty texts, are marked with pink silk ribbons for the dura- tion of the exhibition. -

History of Mormon Exhibits in World Expositions

Brigham Young University BYU ScholarsArchive Theses and Dissertations 1974 History of Mormon Exhibits in World Expositions Gerald Joseph Peterson Brigham Young University - Provo Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/etd Part of the History Commons, Missions and World Christianity Commons, and the Mormon Studies Commons BYU ScholarsArchive Citation Peterson, Gerald Joseph, "History of Mormon Exhibits in World Expositions" (1974). Theses and Dissertations. 5041. https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/etd/5041 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by BYU ScholarsArchive. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of BYU ScholarsArchive. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected]. aloojloo nn HISTORY OF moreonMOMIONMORKON exlEXHIBITSEXI abitsabets IN WELDWRLD expositionsEXPOSI TIMS A thesis presented to the department of church history and doctrine brigham young university in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree master of arts by gerald joseph peterson august 1941974 this thesis by gerald josephjoseph peterson isifc accepted in its pre- sent form by the department of church history and doctrine in the college of religious instruction of brighamBrig hainhalhhajn young university as satis- fyjfyingbyj ng the thesis requirements for the degree of master of arts julyIZJWJL11. 19rh biudiugilgilamQM jwAAIcowan completionemplompl e tion THdatee richardlalial0 committeeCowcomlittee chairman 02v -

Warsaw University Library Tanks and Helicopters

NOWY ŚWIAT STREET Nearby: – military objects. There is an interesting outdoor able cafes and restaurants, as well as elegant UJAZDOWSKIE AVENUE Contemporary Art – a cultural institution and THE WILANÓW PARK exhibition making it possible to admire military boutiques and shops selling products of the an excellent gallery. Below the escarpment, AND PALACE COMPLEX The Mikołaj Kopernik Monument The Warsaw University Library tanks and helicopters. world’s luxury brands. The Ujazdowski Park east of the Castle, there is the Agricola Park (Pomnik Mikołaja Kopernika) (Biblioteka Uniwersytecka w Warszawie) (Park Ujazdowski) and the street of the same name, where street ul. St. Kostki Potockiego 10/16 ul. Dobra 56/66, www.buw.uw.edu.pl The National Museum The St. Alexander’s Church gas lamps are hand lit by lighthouse keepers tel. +48 22 544 27 00 One of the best examples of modern architecture (Muzeum Narodowe) (Kościół św. Aleksandra) just before the dusk and put down at dawn. www.wilanow-palac.art.pl in the Polish capital. In the underground of this Al. Jerozolimskie 3 ul. Książęca 21, www.swaleksander.pl It used to be the summer residence of Jan interesting building there is an entertainment tel. +48 22 621 10 31 A classicist church modelled on the Roman The Botanical Garden III Sobieski, and then August II as well as centre (with bowling, billiards, climbing wall) www.mnw.art.pl Pantheon. It was built at the beginning of the of the Warsaw University the most distinguished aristocratic families. and on the roof there is one of the prettiest One of the most important cultural institutions 19th c. -

Portraits of Sculptors in Modernism

Konstvetenskapliga institutionen Portraits of Sculptors in Modernism Författare: Olga Grinchtein © Handledare: Karin Wahlberg Liljeström Påbyggnadskurs (C) i konstvetenskap Vårterminen 2021 ABSTRACT Institution/Ämne Uppsala universitet. Konstvetenskapliga institutionen, Konstvetenskap Författare Olga Grinchtein Titel och undertitel: Portraits of Sculptors in Modernism Engelsk titel: Portraits of Sculptors in Modernism Handledare Karin Wahlberg Liljeström Ventileringstermin: Höstterm. (år) Vårterm. (år) Sommartermin (år) 2021 The portrait of sculptor emerged in the sixteenth century, where the sitter’s occupation was indicated by his holding a statue. This thesis has focus on portraits of sculptors at the turn of 1900, which have indications of profession. 60 artworks created between 1872 and 1927 are analyzed. The goal of the thesis is to identify new facets that modernism introduced to the portraits of sculptors. The thesis covers the evolution of artistic convention in the depiction of sculptor. The comparison of portraits at the turn of 1900 with portraits of sculptors from previous epochs is included. The thesis is also a contribution to the bibliography of portraits of sculptors. 2 Acknowledgements I would like to thank my supervisor Karin Wahlberg Liljeström for her help and advice. I also thank Linda Hinners for providing information about Annie Bergman’s portrait of Gertrud Linnea Sprinchorn. I would like to thank my mother for supporting my interest in art history. 3 Table of Contents 1. Introduction ....................................................................................................................... -

Jesus Christ by Thorvaldsen

Jesus Christ by Thorvaldsen New cast copy 1:1 (armed alabaster, height 35 cm.) of biscuit-miniature by Chr. Christensen, 1840 Church of Our Lady Trinity Denmark The Cathedral of Copenhagen Knud og Birthe Lund Susanne Torgard, phone: +45 3318 6422 Saint Villads Street 1, 8800 Viborg, Denmark Nørregade 8, 1165 Copenhagen K., Denmark Phone: +45 8662 3621 / +45 2020 3621 Mail: [email protected] Mail: [email protected] www.Domkirken.dk www.Trefoldigheden.dk Front cover photos: Top: The Christus Statue by Bertel Thorvaldsen, Our Lady´s Church, Copenhagen (marble, mounted 1839, modelled 1821 in Rome). Photo reproduced by permission from architect-photographer Jens Frederiksen ©. Bottom: Bertel Thorvaldsen´s selfportrait statue, standing with the Goddess of Hope (1839). Photo reproduced by permission from Thorvaldsens Museum ©. THORVALDSENS THOUGHTS ABOUT HIS Bertel Thorvaldsen´s Christus statue STATUE OF JESUS CHRIST Quotations from: Do you believe in Angels? by Inga Boisen Schmidt Printed by permission by publisher Rubel Blaedel, Rhodos Publishing House @ Thorvaldsen expressed his aim to create He made many draft sketches including “Christ over Millennia”. positions, showing Christ blessing, praying and warning. NEW LIGHT ON THORVALDSENS VIEW ON CHRISTIANITY For a long time, he hesitated, groping towards this major task. One day he stood with his friend, Thorvaldsen was by nature reserved … and it Not until his old days Dalhoff felt obliged Should he create the statue as the suffering Hermann Freund, in front of a sketch, was not easy for him to be open opposite one through some records to let the posterity Christ, the anxious, the humiliated or the showing Christ, praying with upraised another. -

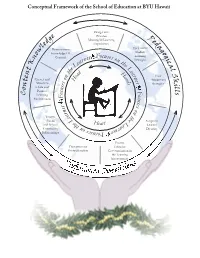

Conceptual Framework of the School of Education at BYU Hawaii

Conceptual Framework of the School of Education at BYU Hawaii Design and Provides e P g Meaningful Learning e ed Experiences d l Uses Active a Demonstrates g w Knowledge Of Student o Focu Learning o Content er ses o g n rn n Strategies i ea th c K L e a L e l t h e t d H a a r S n n e a n Uses e n Creates and o H d e Assessment k r t s s Maintains Strategies i e n a Safe and s l o u l F Positive c s o o C Learning c F u Environment s e s r e o n n r t a h Fosters e e L L Parent Adapts to e Heart e h and School a t Learner r n n o Community e Diversity r s e s u F c Relationships o Fosters Demonstrates Effective Professionalism Communication in the Learning Environment P s rofe ion ssional Disposit Conceptual Framework School of Education Brigham Young University - Hawaii Introduction Located in Laie, a small town on the scenic North Shore of the island of Oahu, Brigham Young University Hawaii is a four year liberal arts institution with an enrollment of 2400 students representing a broad spectrum of cultural backgrounds. Part of a four-campus university system sponsored by The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints (LDS Church), the University has one of the highest percentages of international undergraduate students of any university in the country1, with roughly 48% coming from 70 countries outside the United States2. -

Temple Square Tours

National Association of Women Judges 2015 Annual Conference Salt Lake City, Utah Salt Lake City Temple Square Tours One step through the gates of Temple Square and you’ll be immersed in 35 acres of enchantment in the heart of Salt Lake City. Whether it’s the rich history, the gorgeous gardens and architecture, or the vivid art and culture that pulls you in, you’ll be sure to have an unforgettable experience. Temple Square was founded by Mormon pioneers in 1847 when they arrived in the Salt Lake Valley. Though it started from humble and laborious beginnings (the temple itself took 40 years to build), it has grown into Utah’s number one tourist attraction with over three million visitors per year. The grounds are open daily from 9 a.m. to 9 p.m. and admission is free, giving you the liberty to enjoy all that Temple Square has to offer. These five categories let you delve into your interests and determine what you want out of your visit to Temple Square: Family Adventure Temple Square is full of excitement for the whole family, from interactive exhibits and enthralling films, to the splash pads and shopping at City Creek Center across the street. FamilySearch Center South Visitors’ Center If you’re interested in learning about your family history but not sure where to start, the FamilySearch Center is the perfect place. Located in the lobby level of the Joseph Smith Memorial Building, the FamilySearch Center is designed for those just getting started. There are plenty -1- of volunteers to help you find what you need and walk you through the online programs. -

Art Bulletin of Nationalmuseum Stockholm Volume 26:1

The Danish Golden Age – an Acquisitions Project That Became an Exhibition Magnus Olausson Director of Collections Art Bulletin of Nationalmuseum Stockholm Volume 26:1 Art Bulletin of Nationalmuseum, Stockholm, © Copyright Musei di Strada Nuova, Genova Martin van Meytens’s Portrait of Johann is published with generous support from the (Fig. 4, p. 17) Michael von Grosser: The Business of Nobility Friends of the Nationalmuseum. © National Gallery of Art, Washington D.C. Open © Österreichisches Staatsarchiv 2020 (Fig. 2, Access image download (Fig. 5, p. 17) p. 92) Nationalmuseum collaborates with Svenska Henri Toutin’s Portrait of Anne of Austria. A © Robert Wellington, Canberra (Fig. 5, p. 95) Dagbladet, Bank of America Merrill Lynch, New Acquisition from the Infancy of Enamel © Wien Museum, Vienna, Peter Kainz (Fig. 7, Grand Hôtel Stockholm, The Wineagency and the Portraiture p. 97) Friends of the Nationalmuseum. © Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam/Public Domain (Fig. 2, p. 20) Graphic Design Cover Illustration © Christies, 2018 (Fig. 3, p. 20) BIGG Daniel Seghers (1590–1661) and Erasmus © The Royal Armoury, Helena Bonnevier/ Quellinus the Younger (1607–1678), Flower CC-BY-SA (Fig. 5, p. 21) Layout Garland with the Standing Virgin and Child, c. Four 18th-Century French Draughtsmen Agneta Bervokk 1645–50. Oil on copper, 85.5 x 61.5 cm. Purchase: © The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Wiros Fund. Nationalmuseum, NM 7505. NY/Public Domain (Fig. 7, p. 35) Translation and Language Editing François-André Vincent and Johan Tobias Clare Barnes and Martin Naylor Publisher Sergel. On a New Acquisition – Alcibiades Being Susanna Pettersson, Director General. Taught by Socrates, 1777 Publishing © The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Ludvig Florén, Magnus Olausson, and Martin Editors NY/Public Domain (Fig. -

Article Were Taken by the Author, with the Exception of the Lower Inscription, Which Was Taken by Deidre Green

Christus, by Bertel Thorvaldsen (born 1768 or 1770, died 1844), in the Cathedral of Copenhagen. The Danish words on the pedestal read “Come unto me” (Matt. 11:28). The Christus in Context A Photo Essay John W. Welch mong the many good reasons to go to Copenhagen, Denmark, is to A experience firsthand the famous Christus statue by Bertel Thor- valdsen (1770–1844) in the Vor Frue Kirke (The Church of Our Lady), the Lutheran Cathedral of Copenhagen. While this classic sculpture of Christ, in stunning white Carrara marble, would be impressive in any setting, it is especially meaningful and emotive in its original architec- tural setting.1 Many circumstances providentially welcomed the Apostle Erastus Snow when he and three other missionaries arrived in 1849 in Copen- hagen, the first missionaries of the Restoration to set foot on the con- tinent of Europe.2 Most significantly, only months before their arrival, the Danish constitution had been adopted,3 containing one of the most progressive provisions guaranteeing religious liberty ever to be adopted. This significant constitutional development was the first in the world to follow the Constitution of the United States, fulfilling a hope expressed 1. Anne-Mette Gravgaard and Eva Henschen, On the Statue of Christ by Thorvaldsen (Copenhagen: The Thorvaldsen Museum and the Church of Our Lady, 1997). See also David Bindman, Warm Flesh, Cold Marble: Canova, Thor- valdsen, and Their Critics (New Haven, Conn.: Yale University Press, 2014), Matthew O. Richardson, The Christus Legacy (Sandy, Utah: Leatherwood Press, 2007); and Matthew O. Richardson, “Bertel Thorvaldsen’s Christus: A Mormon Icon,” Journal of Mormon History 29, no. -

Entry 8955. the Great Nauvoo, Illinois, Periodical, Spanning the Duration of the Mormon Sojourn in Illinois

Entry 8955. The great Nauvoo, Illinois, periodical, spanning the duration of the Mormon sojourn in Illinois. From the Brigham Young University collection. T TABERNACLE TESTIMONIAL CONCERT ... 8564. Tabernacle testimonial concert to Prof. George Careless, of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, by O. F. Whitney. Salt Monday, June 10th, 1907, at 8:15 P.M. [Salt Lake City], The Lake City, Geo. Q. Cannon and Sons Company, [1900?]. Deseret News, 1907. [64]p. 19 x 27cm. plates, ports. [12]p. 20cm. port. MH, NjP, USlC, UU Includes a brief biography of Careless. UPB, USlC 8569. Talbot, Ethelbert. My people of the plains, by the Right Reverend Ethelbert Talbot, D.D., S.T.D. bishop of cen- 8565. Tadje, Fred. Die Prinzipien des Evangeliums. Basel, tral Pennsylvania. New York and London, Harper & Schweizerische und Deutsche Mission der Kirche Jesu Brothers Publishers, 1906. Christi der Heiligen der Letzten Tage, 1925. x, [1]p., [1]l., 264, [1]p. 22cm. plates, ports. 104p. 20cm. (Leitfaden für die “The experiences herein related took place during Lehrerfortbildungs-klassen) the eleven years in which the author ministered as a Title in English: The principles of the gospel. bishop to the pioneers of the Rocky Mountain region” At head of title: Schweizerische und Deutsche after 1887. Mission der Kirche Jesu Christi der Heiligen der Chapter on Mormonism, p. 215–40. Letzten Tage. DLC, MB, MiU, NjP, NN, OCl, UHi, ULA, UPB, UPB, USlC USl, USlC, UU, WaS, WaSp, WaV 8566. ———. A vital message to the elders. A letter by a mis- 8570. Talbot, Grace. Much-married Saints and some sinners. -

Press Release Beauty and Revolution

PRESS RELEASE BEAUTY AND REVOLUTION. NEOCLASSICISM 1770–1820 20 FEBRUARY–26 MAY 2013 Press preview: Tuesday, 19 February 2013, 11 am Städel Museum, Exhibition House Frankfurt am Main, 19 December 2012. A comprehensive special exhibition Städelsches Kunstinstitut und Städtische Galerie presented by Frankfurt’s Städel Museum from 20 February to 26 May 2013 will Dürerstraße 2 highlight the art of Neoclassicism and the impulses it provided for Romanticism. 60596 Frankfurt am Main Phone +49(0)69-605098-170 Developed in collaboration with the Liebieghaus Skulpturensammlung, the show Fax +49(0)69-605098-111 Beauty and Revolution will assemble about one hundred works of the period from [email protected] www.staedelmuseum.de 1770 to 1820 by such artists as Anton Raphael Mengs, Thomas Banks, Antonio PRESS DOWNLOADS Canova, Jacques-Louis David, Bertel Thorvaldsen, Johann Gottfried Schadow, and www.staedelmuseum.de Jean-August-Dominique Ingres. The major survey, whose range also comprises a PRESS AND PUBLIC RELATIONS Axel Braun, head number of impressive examples of “Romantic Neoclassicism,” will be the first in Phone +49(0)69-605098-170 Germany to convey an idea of the variety of the different and sometimes even Fax +49(0)69-605098-188 [email protected] contradictory facets of this style. Sarah Heider, press officer Phone +49(0)69-605098-195 Fax +49(0)69-605098-188 Based on significant sculptures, paintings, and prints from collections in many [email protected] countries, the exhibition will explore the decisive influence of classical antiquity on Silke Janßen, press officer the artists of the era. Struggling for a socially relevant art, the artists directed their Phone +49(0)69-605098-234 Fax +49(0)69-605098-188 attention to the aesthetics of Greek and Roman art as well as to their virtues and [email protected] moral standards conveyed by history and mythology.