Webcasting and Convergence: Policy Implications”, OECD Digital Economy Papers, No

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

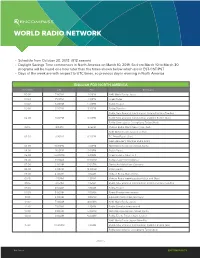

World Radio Network

WORLD RADIO NETWORK • Schedule from October 28, 2018 (B18 season) • Daylight Savings Time commences in North America on March 10, 2019. So from March 10 to March 30 programs will be heard one hour later than the times shown below which are in EST/CST/PST • Days of the week are with respect to UTC times, so previous day in evening in North America ENGLISH FOR NORTH AMERICA UTC/GMT EST PST Programs 00:00 7:00PM 4:00PM NHK World Radio Japan 00:30 7:30PM 4:30PM Israel Radio 01:00 8:00PM 5:00PM Radio Prague 00:30 8:30PM 5:30PM Radio Slovakia Radio New Zealand International: Korero Pacifica (Tue-Sat) 02:00 9:00PM 6:00PM Radio New Zealand International: Dateline Pacific (Sun) Radio Guangdong: Guangdong Today (Mon) 02:15 9:15PM 6:15PM Vatican Radio World News (Tue - Sat) NHK World Radio Japan (Tue-Sat) 02:30 9:30PM 6:30PM PCJ Asia Focus (Sun) Glenn Hauser’s World of Radio (Mon) 03:00 10:00PM 7:00PM KBS World Radio from Seoul, Korea 04:00 11:00PM 8:00PM Polish Radio 05:00 12:00AM 9:00PM Israel Radio – News at 8 06:00 1:00AM 10:00PM Radio France International 07:00 2:00AM 11:00PM Deutsche Welle from Germany 08:00 3:00AM 12:00AM Polish Radio 09:00 4:00AM 1:00AM Vatican Radio World News 09:15 4:15AM 1:15AM Vatican Radio weekly podcast (Sun and Mon) 09:15 4:15AM 1:15AM Radio New Zealand International: Korero Pacifica (Tue-Sat) 09:30 4:30AM 1:30AM Radio Prague 10:00 5:00AM 2:00AM Radio France International 11:00 6:00AM 3:00AM Deutsche Welle from Germany 12:00 7:00AM 4:00AM NHK World Radio Japan 12:30 7:30AM 4:30AM Radio Slovakia International 13:00 -

COMMUNICATION and ADVERTISING This Text Is Prepared for The

DESIGN CHRONOLOGY TURKEY COMMUNICATION AND ADVERTISING This text is prepared for the 3rd Istanbul Design Biennial ARE WE HUMAN? The Design of the Species 2 seconds, 2 days, 2 years, 200 years, 200,000 years by Gökhan Akçura and Pelin Derviş with contributions by Barış Gün and the support of Studio-X Istanbul translated by Liz Erçevik Amado, Selin Irazca Geray and Gülce Maşrabacı editorial support by Ceren Şenel, Erim Şerifoğlu graphic design by Selin Pervan COMMUNICATION AND ADVERTISING 19th CENTURY perfection of the manuscripts they see in Istanbul. Henry Caillol, who grows an interest in and learns about lithography ALAMET-İ FARİKA (TRADEMARK) in France, figures that putting this technique into practice in Let us look at the market places. The manufacturer wants to Istanbul will be a very lucrative business and talks Jacques distinguish his goods; the tradesman wants to distinguish Caillol out of going to Romania. Henry Caillol hires a teacher his shop. His medium is the sign. He wants to give the and begins to learn Turkish. After a while, also relying on the consumer a message. He is trying to call out “Recognize me”. connections they have made, they apply to the Ministry of He is hanging either a model of his product, a duplicate of War and obtain permission to found a lithographic printing the tool he is working with in front of his store, or its sign, house. They place an order for a printing press from France. one that is diferent, interesting. The tailor hangs a pair of This printing house begins to operate in the annex of the scissors and he becomes known as “the one who is good with Ministry of War (the current Istanbul University Rectorate scissors”. -

Download Article (PDF)

Advances in Social Science, Education and Humanities Research, volume 123 2nd International Conference on Education, Sports, Arts and Management Engineering (ICESAME 2017) The Application of New Media Technology in the Ideological and Political Education of College Students Hao Lu 1, a 1 Jiangxi Vocational & Technical College of Information Application, Nanchang, China [email protected] Keywords: new media; application; the Ideological and Political Education Abstract: With the development of science and technology, new media technology has been more widely used in teaching. In particular, the impact of new media technology on college students’ ideological and political education is very important. The development of new media technology has brought the opportunities to college students’ ideological and political education while bringing the challenges. Therefore, it is an urgent task to study on college students’ ideological and political education under the new media environment. 1. Introduction New media technology, relative to traditional media technology, is the emerging electronic media technology on the basis of digital technology, internet technology, mobile communication technology, etc. it mainly contains fetion, wechat, blog, podcast, network television, network radio, online games, digital TV, virtual communities, portals, search engines, etc. With the rapid development and wide application of science and technology, new media technology has profoundly affected students’ learning and life. Of course, it also brings new challenges and opportunities to college students’ ideological and political education. Therefore, how to better use the new media technology to improve college students’ ideological and political education becomes the problems needing to be solving by college moral educators. 2. The intervention mode and its characteristics of new media technology New media technology, including blog, instant messaging tools, streaming media, etc, is a new network tools and application mode and instant messaging carriers under the network environment. -

Digital Audio Broadcasting : Principles and Applications of Digital Radio

Digital Audio Broadcasting Principles and Applications of Digital Radio Second Edition Edited by WOLFGANG HOEG Berlin, Germany and THOMAS LAUTERBACH University of Applied Sciences, Nuernberg, Germany Digital Audio Broadcasting Digital Audio Broadcasting Principles and Applications of Digital Radio Second Edition Edited by WOLFGANG HOEG Berlin, Germany and THOMAS LAUTERBACH University of Applied Sciences, Nuernberg, Germany Copyright ß 2003 John Wiley & Sons Ltd, The Atrium, Southern Gate, Chichester, West Sussex PO19 8SQ, England Telephone (þ44) 1243 779777 Email (for orders and customer service enquiries): [email protected] Visit our Home Page on www.wileyeurope.com or www.wiley.com All Rights Reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, scanning or otherwise, except under the terms of the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988 or under the terms of a licence issued by the Copyright Licensing Agency Ltd, 90 Tottenham Court Road, London W1T 4LP, UK, without the permission in writing of the Publisher. Requests to the Publisher should be addressed to the Permissions Department, John Wiley & Sons Ltd, The Atrium, Southern Gate, Chichester, West Sussex PO19 8SQ, England, or emailed to [email protected], or faxed to (þ44) 1243 770571. This publication is designed to provide accurate and authoritative information in regard to the subject matter covered. It is sold on the understanding that the Publisher is not engaged in rendering professional services. If professional advice or other expert assistance is required, the services of a competent professional should be sought. -

Audience Affect, Interactivity, and Genre in the Age of Streaming TV

. Volume 16, Issue 2 November 2019 Navigating the Nebula: Audience affect, interactivity, and genre in the age of streaming TV James M. Elrod, University of Michigan, USA Abstract: Streaming technologies continue to shift audience viewing practices. However, aside from addressing how these developments allow for more complex serialized streaming television, not much work has approached concerns of specific genres that fall under the field of digital streaming. How do emergent and encouraged modes of viewing across various SVOD platforms re-shape how audiences affectively experience and interact with genre and generic texts? What happens to collective audience discourses as the majority of viewers’ situated consumption of new serial content becomes increasingly accelerated, adaptable, and individualized? Given the range and diversity of genres and fandoms, which often intersect and overlap despite their current fragmentation across geographies, platforms, and lines of access, why might it be pertinent to reconfigure genre itself as a site or node of affective experience and interactive, collective production? Finally, as studies of streaming television advance within the industry and academia, how might we ponder on a genre-by- genre basis, fandoms’ potential need for time and space to collectively process and interact affectively with generic serial texts – in other words, to consider genres and generic texts themselves as key mediative sites between the contexts of production and those of fans’ interactivity and communal, affective pleasure? This article draws together threads of commentary from the industry, scholars, and culture writers about SVOD platforms, emergent viewing practices, speculative genres, and fandoms to argue for the centrality of genre in interventions into audience studies. -

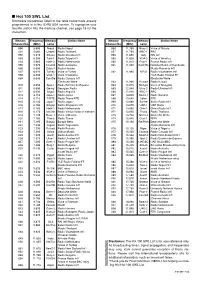

Hot 100 SWL List Shortwave Frequencies Listed in the Table Below Have Already Programmed in to the IC-R5 USA Version

I Hot 100 SWL List Shortwave frequencies listed in the table below have already programmed in to the IC-R5 USA version. To reprogram your favorite station into the memory channel, see page 16 for the instruction. Memory Frequency Memory Station Name Memory Frequency Memory Station Name Channel No. (MHz) name Channel No. (MHz) name 000 5.005 Nepal Radio Nepal 056 11.750 Russ-2 Voice of Russia 001 5.060 Uzbeki Radio Tashkent 057 11.765 BBC-1 BBC 002 5.915 Slovak Radio Slovakia Int’l 058 11.800 Italy RAI Int’l 003 5.950 Taiw-1 Radio Taipei Int’l 059 11.825 VOA-3 Voice of America 004 5.965 Neth-3 Radio Netherlands 060 11.910 Fran-1 France Radio Int’l 005 5.975 Columb Radio Autentica 061 11.940 Cam/Ro National Radio of Cambodia 006 6.000 Cuba-1 Radio Havana /Radio Romania Int’l 007 6.020 Turkey Voice of Turkey 062 11.985 B/F/G Radio Vlaanderen Int’l 008 6.035 VOA-1 Voice of America /YLE Radio Finland FF 009 6.040 Can/Ge Radio Canada Int’l /Deutsche Welle /Deutsche Welle 063 11.990 Kuwait Radio Kuwait 010 6.055 Spai-1 Radio Exterior de Espana 064 12.015 Mongol Voice of Mongolia 011 6.080 Georgi Georgian Radio 065 12.040 Ukra-2 Radio Ukraine Int’l 012 6.090 Anguil Radio Anguilla 066 12.095 BBC-2 BBC 013 6.110 Japa-1 Radio Japan 067 13.625 Swed-1 Radio Sweden 014 6.115 Ti/RTE Radio Tirana/RTE 068 13.640 Irelan RTE 015 6.145 Japa-2 Radio Japan 069 13.660 Switze Swiss Radio Int’l 016 6.150 Singap Radio Singapore Int’l 070 13.675 UAE-1 UAE Radio 017 6.165 Neth-1 Radio Netherlands 071 13.680 Chin-1 China Radio Int’l 018 6.175 Ma/Vie Radio Vilnius/Voice -

Comeseetv Streaming Guide and Proposal

ComeSeeTv USA, Inc ComeSeeTv Streaming Guide and Proposal Cultural Live Streaming Done Right! ComeSeeTv – Can You See Me Now! 1 ComeSeeTv streaming proposal About Us ComeSeeTv is all of the following three things: First it is a global video content delivery platform that allows anyone to reliably stream their video content. Next, a website that pulls the individual channels of all our members to one place to increase the visibility of their content. Third, we are an agent for cultural development and unity across the Caribbean. When patrons pay to watch live streams on ComeSeeTv they are directly supporting the event organizer, or community! Why we’re different: Our webcasting solution concentrates on the viewer and is usually mixed live by a creative professional, so in essence our video stream experience looks and feels more like a TV production which our collective cultures deserve. Plus, though we are primarily a content delivery network service provider, we assign our global agents to oversee every stream of our clients, and to offer technical support to your customers. Nonetheless, ComeSeeTv was not designed to and does not compete with local streaming service providers in any country as our primary business is content delivery. Our streaming website is extremely secure and can be suited to match your business model as closely as possible. We are also able to handle the high visitor loads associated with all your events. Many local streaming service providers around the Caribbean are currently using ComeSeeTv to deliver video to their clientele 24/7. Four Main Package Offers 1. Event Streaming Using the very latest video mixing technology we can simultaneously project, live stream and record your event. -

QUESTION 20-1/2 Examination of Access Technologies for Broadband Communications

International Telecommunication Union QUESTION 20-1/2 Examination of access technologies for broadband communications ITU-D STUDY GROUP 2 3rd STUDY PERIOD (2002-2006) Report on broadband access technologies eport on broadband access technologies QUESTION 20-1/2 R International Telecommunication Union ITU-D THE STUDY GROUPS OF ITU-D The ITU-D Study Groups were set up in accordance with Resolutions 2 of the World Tele- communication Development Conference (WTDC) held in Buenos Aires, Argentina, in 1994. For the period 2002-2006, Study Group 1 is entrusted with the study of seven Questions in the field of telecommunication development strategies and policies. Study Group 2 is entrusted with the study of eleven Questions in the field of development and management of telecommunication services and networks. For this period, in order to respond as quickly as possible to the concerns of developing countries, instead of being approved during the WTDC, the output of each Question is published as and when it is ready. For further information: Please contact Ms Alessandra PILERI Telecommunication Development Bureau (BDT) ITU Place des Nations CH-1211 GENEVA 20 Switzerland Telephone: +41 22 730 6698 Fax: +41 22 730 5484 E-mail: [email protected] Free download: www.itu.int/ITU-D/study_groups/index.html Electronic Bookshop of ITU: www.itu.int/publications © ITU 2006 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, by any means whatsoever, without the prior written permission of ITU. International Telecommunication Union QUESTION 20-1/2 Examination of access technologies for broadband communications ITU-D STUDY GROUP 2 3rd STUDY PERIOD (2002-2006) Report on broadband access technologies DISCLAIMER This report has been prepared by many volunteers from different Administrations and companies. -

How to Choose a Search Engine Or Directory

How to Choose a Search Engine or Directory Fields & File Types If you want to search for... Choose... Audio/Music AllTheWeb | AltaVista | Dogpile | Fazzle | FindSounds.com | Lycos Music Downloads | Lycos Multimedia Search | Singingfish Date last modified AllTheWeb Advanced Search | AltaVista Advanced Web Search | Exalead Advanced Search | Google Advanced Search | HotBot Advanced Search | Teoma Advanced Search | Yahoo Advanced Web Search Domain/Site/URL AllTheWeb Advanced Search | AltaVista Advanced Web Search | AOL Advanced Search | Google Advanced Search | Lycos Advanced Search | MSN Search Search Builder | SearchEdu.com | Teoma Advanced Search | Yahoo Advanced Web Search File Format AllTheWeb Advanced Web Search | AltaVista Advanced Web Search | AOL Advanced Search | Exalead Advanced Search | Yahoo Advanced Web Search Geographic location Exalead Advanced Search | HotBot Advanced Search | Lycos Advanced Search | MSN Search Search Builder | Teoma Advanced Search | Yahoo Advanced Web Search Images AllTheWeb | AltaVista | The Amazing Picture Machine | Ditto | Dogpile | Fazzle | Google Image Search | IceRocket | Ixquick | Mamma | Picsearch Language AllTheWeb Advanced Web Search | AOL Advanced Search | Exalead Advanced Search | Google Language Tools | HotBot Advanced Search | iBoogie Advanced Web Search | Lycos Advanced Search | MSN Search Search Builder | Teoma Advanced Search | Yahoo Advanced Web Search Multimedia & video All TheWeb | AltaVista | Dogpile | Fazzle | IceRocket | Singingfish | Yahoo Video Search Page Title/URL AOL Advanced -

IATSE LOCAL 16 CURRENT CONTRACT Theatrical Workers

2016 PROJECT COLLECTIVE BARGAINING AGREEMENT BETWEEN CITY & COUNTY OF SAN FRANCISCO AND INTERNATIONAL ALLIANCE OF THEATRICAL STAGE EMPLOYEES, MOVING PICTURE TECHNICIANS, ARTISTS AND ALLIED CRAFTS OF THE UNITED STATES, ITS TERRITORIES AND CANADA LOCAL N0.16 Local 16 l.A.T.S.E. 240 Second Street, First Floor San Francisco, CA 94105 Tel: 415-441-6400 Fax: 415-243-0179 www.local16.org XX TABLE OF CONTENTS PAGE I. GENERAL PROVISIONS 4 A. Witnesseth 4 B. Recognition 4 C. Scope and Jurisdiction 4 D. Compensation 4 E. Rules and Regulations 5 F. New Categories and Classifications 5 II. DEFINITIONS 5 A. Rigging 5 B. Head of Department Rate 5 C. Multi-Source Technology 6 D. Multi-Source Technician 6 E. Computer Software Technician 7 F. General Computer Technician 7 G. General Audio Visual 7 H. Steward 7 I. Base Rate 7 J. Moscone Center Exhibit Booths Only 7 Ill. CONDITIONS 8 A. Work Week 8 B. Hourly Wage Calculations 8 C. Minimum Calls 8 D. Straight Time 8 E. Nine Hour Rest Period 8 F. Time and One-Half Rate 8 G. Double Time Rate 9 H. Un-Worked Hours 9 I. Vacation Pay 9 J. Meal Periods 9 K. Higher Scale 1O L. Holidays 1O M. Rates and Conditions 10 N. Cancellation of Calls 10 IV. FRINGE BENEFITS, WORK FEES AND PAYROLL 10 A. Health and Welfare 1O B. Pension 11 C. Check-Off Work Fees 11 D. Training and Certification Program Employer Contribution 11 E. Sick Leave 11 F. Reporting of Fringe Benefits and Work Fees 11 G. -

Navigating the Tangled Web of Webcasting Royalties

To make matters more complicated, Navigating the Tangled Web most recorded songs also have multiple copyright owners. Songwriters, compos- of Webcasting Royalties ers, and publishers of a musical composi- tion (a “song”) have rights in the song. BY CYDNEY A. TUNE AND CHRISTOPHER R. LOCKARD For example, these owners have the right to receive royalties every time a copy of the song is sold in sheet music form or ver since Napster launched to Services such as iTunes sell permanent as part of an album, as well as when the enormous popularity in 1999 and downloads and ringtones that consum- song is broadcast over the radio, the In- Edrew the ire of heavy metal band ers download to their computers and ternet, speakers in a restaurant, or when Metallica, the record industry has looked cell phones. Other companies, such as it is performed in a concert. Addition- at online music with a highly suspicious Amazon.com, sell physical phonorecords ally, artists who perform on a recorded and combative eye. The last decade has (like records and CDs). Music is also version of a song (a “sound recording”), seen record labels fight numerous Web contained in other online content, such and the owner of the copyrights in that sites and software makers that have fa- as podcasts, commercials, and videos car- sound recording (generally the record cilitated the distribution of online music ried on Web sites like YouTube. Finally, label), also have the right to receive and even individuals who simply shared thousands of Web sites, known as web- royalties for sales of that sound recording or downloaded music. -

Streaming Media Seminar – Effective Development and Distribution Of

Proceedings of the 2004 ASCUE Conference, www.ascue.org June 6 – 10, 1004, Myrtle Beach, South Carolina Streaming Media Seminar – Effective Development and Distribution of Streaming Multimedia in Education Robert Mainhart Electronic Classroom/Video Production Manager James Gerraughty Production Coordinator Kristine M. Anderson Distributed Learning Course Management Specialist CERMUSA - Saint Francis University P.O. Box 600 Loretto, PA 15940-0600 814-472-3947 [email protected] This project is partially supported by the Center of Excellence for Remote and Medically Under- Served Areas (CERMUSA) at Saint Francis University, Loretto, Pennsylvania, under the Office of Naval Research Grant Number N000140210938. Introduction Concisely defined, “streaming media” is moving video and/or audio transmitted over the Internet for immediate viewing/listening by an end user. However, at Saint Francis University’s Center of Excellence for Remote and Medically Under-Served Areas (CERMUSA), we approach stream- ing media from a broader perspective. Our working definition includes a wide range of visual electronic multimedia that can be transmitted across the Internet for viewing in real time or saved as a file for later viewing. While downloading and saving a media file for later play is not, strictly speaking, a form of streaming, we include that method in our discussion of multimedia content used in education. There are numerous media types and within most, multiple hardware and software platforms used to develop and distribute video and audio content across campus or the Internet. Faster, less expensive and more powerful computers and related tools brings the possibility of content crea- tion, editing and distribution into the hands of the content creators.