Artie's Small Black Eyes Glittered and His Cheeks Began to Turn a Deep Red

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

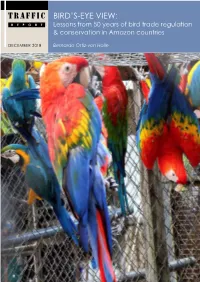

TRAFFIC Bird’S-Eye View: REPORT Lessons from 50 Years of Bird Trade Regulation & Conservation in Amazon Countries

TRAFFIC Bird’s-eye view: REPORT Lessons from 50 years of bird trade regulation & conservation in Amazon countries DECEMBER 2018 Bernardo Ortiz-von Halle About the author and this study: Bernardo Ortiz-von Halle, a biologist and TRAFFIC REPORT zoologist from the Universidad del Valle, Cali, Colombia, has more than 30 years of experience in numerous aspects of conservation and its links to development. His decades of work for IUCN - International Union for Conservation of Nature and TRAFFIC TRAFFIC, the wildlife trade monitoring in South America have allowed him to network, is a leading non-governmental organization working globally on trade acquire a unique outlook on the mechanisms, in wild animals and plants in the context institutions, stakeholders and challenges facing of both biodiversity conservation and the conservation and sustainable use of species sustainable development. and ecosystems. Developing a critical perspective The views of the authors expressed in this of what works and what doesn’t to achieve lasting conservation goals, publication do not necessarily reflect those Bernardo has put this expertise within an historic framework to interpret of TRAFFIC, WWF, or IUCN. the outcomes of different wildlife policies and actions in South America, Reproduction of material appearing in offering guidance towards solutions that require new ways of looking at this report requires written permission wildlife trade-related problems. Always framing analysis and interpretation from the publisher. in the midst of the socioeconomic and political frameworks of each South The designations of geographical entities in American country and in the region as a whole, this work puts forward this publication, and the presentation of the conclusions and possible solutions to bird trade-related issues that are material, do not imply the expression of any linked to global dynamics, especially those related to wildlife trade. -

AMAZONS Rare Birds Tures That Evolved with Relatively Few by Enemies, They Are Not Very Bright

inbred, due to the small size of their numbers and habitat. Like most crea AMAZONS Rare Birds tures that evolved with relatively few by enemies, they are not very bright. John and Pat Stoodley at the The humble park pigeon is canny and 135 pages, 8-1/4"x 11-1/4" street-wise compared to the pink 85 full color plates pigeon. Rio Grande As part of a cooperative breeding program with the Jersey Wildlife Zoo Trust the Bronx Zoo, San Diego Zoo, ~thers by Sherry Rind and the Rio Grande Zoo has Redmon~ Washmgron maintained Pink Pigeons since the seventies. The original pair is still at the zoo and successfully raises its Although small, the Rio Grande own babies in the zoo's indoor jungle Zoo in Albuquerque, New Mexico habitat after having been offered vari breeds and maintains an important ous habitats and nesting spots. collection of rare birds under the Also living in the steamy, indoor stewardship of Curator Bill Aragon. It jungle is a pair of Helmeted Curas is one of the few places in the United sows, large pheasant-like birds. The States to which Australia will send its $78.00 plus $2.50 shipping male sports a bright blue helmet and native birds. To achieve such an envi makes a deep, low-pitched booming Dale R. Thompson able status, the zoo had to petition the sound. On their first day out of quar P.O. Box 1122, Dept. AF Australian government. Every three antine after their arrival from Albu Canyon Country, CA 91386 years, the birds are inspected by the querque's sister city Guadalajara, (Calif. -

Neotropical News Neotropical News

COTINGA 1 Neotropical News Neotropical News Brazilian Merganser in Argentina: If the survey’s results reflect the true going, going … status of Mergus octosetaceus in Argentina then there is grave cause for concern — local An expedition (Pato Serrucho ’93) aimed extinction, as in neighbouring Paraguay, at discovering the current status of the seems inevitable. Brazilian Merganser Mergus octosetaceus in Misiones Province, northern Argentina, During the expedition a number of sub has just returned to the U.K. Mergus tropical forest sites were surveyed for birds octosetaceus is one of the world’s rarest — other threatened species recorded during species of wildfowl, with a population now this period included: Black-fronted Piping- estimated to be less than 250 individuals guan Pipile jacutinga, Vinaceous Amazon occurring in just three populations, one in Amazona vinacea, Helmeted Woodpecker northern Argentina, the other two in south- Dryocopus galeatus, White-bearded central Brazil. Antshrike Biata s nigropectus, and São Paulo Tyrannulet Phylloscartes paulistus. Three conservation biologists from the U.K. and three South American counter PHIL BENSTEAD parts surveyed c.450 km of white-water riv Beaver House, Norwich Road, Reepham, ers and streams using an inflatable boat. Norwich, NR10 4JN, U.K. Despite exhaustive searching only one bird was located in an area peripheral to the species’s historical stronghold. Former core Black-breasted Puffleg found: extant areas (and incidently those with the most but seriously threatened. protection) for this species appear to have been adversely affected by the the Urugua- The Black-breasted Puffleg Eriocnemis í dam, which in 1989 flooded c.80 km of the nigrivestis has been recorded from just two Río Urugua-í. -

A New Parrot Taxon from the Yucatán Peninsula, Mexico—Its Position Within Genus Amazona Based on Morphology and Molecular Phylogeny

A new parrot taxon from the Yucatán Peninsula, Mexico—its position within genus Amazona based on morphology and molecular phylogeny Tony Silva1, Antonio Guzmán2, Adam D. Urantówka3 and Paweª Mackiewicz4 1 Miami, FL, United States of America 2 Laboratorio de Ornitología, Facultad de Ciencias Biológicas, Universidad Autónoma de Nuevo León, Nuevo León, Mexico 3 Department of Genetics, Wroclaw University of Environmental and Life Sciences, Wroclaw, Poland 4 Faculty of Biotechnology, University of Wrocªaw, Wrocªaw, Poland ABSTRACT Parrots (Psittaciformes) are a diverse group of birds which need urgent protection. However, many taxa from this order have an unresolved status, which makes their conservation difficult. One species-rich parrot genus is Amazona, which is widely distributed in the New World. Here we describe a new Amazona form, which is endemic to the Yucatán Peninsula. This parrot is clearly separable from other Amazona species in eleven morphometric characters as well as call and behavior. The clear differences in these features imply that the parrot most likely represents a new species. In contrast to this, the phylogenetic tree based on mitochondrial markers shows that this parrot groups with strong support within A. albifrons from Central America, which would suggest that it is a subspecies of A. albifrons. However, taken together tree topology tests and morphometric analyses, we can conclude that the new parrot represents a recently evolving species, whose taxonomic status should be further confirmed. This lineage diverged from its closest relative about 120,000 years ago and was subjected to accelerated morphological and behavioral changes like some other representatives of the Submitted 14 December 2016 genus Amazona. -

The Grand Cayman Amazon Parrot

Our 1985 convention will be held in the beautiful Cathedral Hotel, San Fran· cisco (Van Ness Avenue and Geary Street), August 7th through 11th. Some ofthe most celebrated speakers in the world will bring us words of wisdom on flora and fauna. Many new The Grand Cayman faces - first timers! There will be tours of San Francisco, the city's zoo, bird tours, and a special Amazon Parrot tour of the wine country. We are working on a "special" to Hawaii, and if you have time, take the 12 day Loveboat Cruise to by Tony Silva Alaska! North Riverside, Illinois This year the drawing will consist of an automobile, a home computer, a color TV., a pair of blue Indian ringnecks, a case of fine wine, a round trip for two to Between cloud formations one thereafter. Australia via Qantas Airlines, twenty· could see a stretch of land in the Grand Cayman is flat, with consider five assorted pairs of birds and many distance. With passing minutes it able stands ofmangrove in the interior, other prizes. became clearer and finally one could the habitat of the parrot. It was on The next Watchbird will carry more de· see palm trees. We then made our de slightly swampy ground, on the north tailed information and all A.F.A. members will soon receive a packet in scent on Grand Cayman, an island 37 ernpart ofthe island, that I had myfirst the mail. In the meantime one can con· lan. (23 mi.) long that lies some 280 close meeting with this extremely en tact: Jim Coffman, convention chairman, lan. -

"The Great Wildlife Heist" PBS Airdate: March 11, 1997 ANNOUNCER: Tonight on NOVA, Bagging and Smuggling Exotic Birds Has Become a Huge International Crime

"The Great Wildlife Heist" PBS Airdate: March 11, 1997 ANNOUNCER: Tonight on NOVA, bagging and smuggling exotic birds has become a huge international crime. DR. THOMAS GOLDSMITH: We see them coming in suitcases, and ridiculous numbers of them are dead. ANNOUNCER: NOVA goes underground with federal agents in an extraordinary sting operation as they try to expose the masterminds behind this multimillion dollar business. TONY SILVA: It is competition, it is fierce and greed. ANNOUNCER: Can the feds stop "The Great Wildlife Heist?" NOVA is funded by Merck. Merck. Pharmaceutical research. Dedicated to preventing disease and improving health. Merck. Committed to bringing out the best in medicine. And by Prudential. Prudential. Insurance, health care, real estate, and financial services. For more than a century, bringing strength and stability to America's families. The Corporation for Public Broadcasting. And viewers like you. NARRATOR: These bird may be the most intelligent descendants of the dinosaurs, and that may be their undoing. Parrots have flourished throughout the tropics and subtropics, more than 300 species of them, in all sizes and every conceivable color. But now they are disappearing from the wild, even as they multiply as pets, an unnatural evolution of wild creatures into collectors' items and commodities. TONY SILVA: If you have one, you have to have two. You then have to have three, four, five, six, seven, eight, nine, ten. One isn't enough. And this is the obsession that bird people go through. NARRATOR: How did so many endangered parrots from distant forests find their way into American cages when laws forbid their import? A special breed of cop, a team of wildlife investigators, has been tracking down the answer to that question. -

2. Birds of South America

TRAFFIC Bird’s-eye view: REPORT Lessons from 50 years of bird trade regulation & conservation in Amazon countries DECEMBER 2018 Bernardo Ortiz-von Halle About the author and this study: Bernardo Ortiz-von Halle, a biologist and TRAFFIC REPORT zoologist from the Universidad del Valle, Cali, Colombia, has more than 30 years of experience in numerous aspects of conservation and its links to development. His decades of work for IUCN - International Union for Conservation of Nature and TRAFFIC TRAFFIC, the wildlife trade monitoring in South America have allowed him to network, is a leading non-governmental organization working globally on trade acquire a unique outlook on the mechanisms, in wild animals and plants in the context institutions, stakeholders and challenges facing of both biodiversity conservation and the conservation and sustainable use of species sustainable development. and ecosystems. Developing a critical perspective The views of the authors expressed in this of what works and what doesn’t to achieve lasting conservation goals, publication do not necessarily reflect those Bernardo has put this expertise within an historic framework to interpret of TRAFFIC, WWF, or IUCN. the outcomes of different wildlife policies and actions in South America, Reproduction of material appearing in offering guidance towards solutions that require new ways of looking at this report requires written permission wildlife trade-related problems. Always framing analysis and interpretation from the publisher. in the midst of the socioeconomic and political frameworks of each South The designations of geographical entities in American country and in the region as a whole, this work puts forward this publication, and the presentation of the conclusions and possible solutions to bird trade-related issues that are material, do not imply the expression of any linked to global dynamics, especially those related to wildlife trade. -

THE DIGITAL EDITION Parrot

THE DIGITAL EDITION parrot Volume 6 Issue 11 April 2020 ISSN 1176-0761 IN THIS ISSUE: PSNZ Northland Branch Bird Sale Breeding Ban Ruffles Feathers Stimulating Breeding in Parrots Eclectus in New Zealand Training Techniques for Parrots Photo © Simon Degenhard Photography Parrot Society Committee 2019 – 2020 PRESIDENT Mary-lee Sloan Ph (027) 448 7816 [email protected] SECRETARY Heather Flowers Ph (09) 420 2500 Mob 021 059 1192 [email protected] VICE PRESIDENT Mark Davies [email protected] SHADOW Hayden van Hoof Ph (022) 315 0363 VICE PRESIDENT [email protected] TREASURER & Gavin White Ph (09) 407 6611 MEMBERSHIP STEWARD [email protected] SERVICES Mary-lee Sloan Ph (027) 448 7816 [email protected] MAGAZINE EDITOR Yvette Harris Ph (027) 480 9347 [email protected] WEBSITE Brian Flowers Ph (09) 420 2500 Mob (021) 039 4007 [email protected] ADVERTISING Chris Patterson Ph (09) 625 6707 [email protected] NEWSLETTER Christine Matthews Ph (07) 868 5339 Mob (027) 442 2466 [email protected] GENERAL COMMITTEE: Kevin Pulman, Brian Flowers, Uli Elmiger, Ph (07) 823 0466, Email: [email protected] Fred Mead, [email protected] PATRON Davy Jones LIFE MEMBERS Davy Jones, John Warne, Ferry Moormann, Jim Trevett REGIONAL CONTACTS: Waikato: Uli Elmiger (07) 823 0466 Email: [email protected] Palmerston North: Richard and Kerry Dodunski, (06) 323 8339, Email: [email protected] NORTHLAND BRANCH PRESIDENT: Dave Bentley (President) 027 633 3249 or 09 439 2999 VISIT OUR WEBSITE www.parrot.co.nz H NEWS H INFORMATION H SERVICES H MEMBERSHIP PARROT SOCIETY IS ON FACEBOOK! We’d love you to become a fan! Keep up with the latest news & gossip. -

HARI Donates Genuine Replicas of Rare Parrot Book to Think Parrots Show and to Two Leading Parrot Conservationists

News Release July 1, 2014 HARI donates genuine replicas of rare parrot book to Think Parrots Show and to two leading parrot conservationists MONTREAL, Canada – July 1, 2014 – HARI donated genuine replicas A cofounder of the World Parrot Trust, her three main goals are to widely of a rare parrot book, entitled 1883 Vogelbilder Aus Fernen Zonen der publish information which will lead to a better standard of care for captive PAPAGEIEN von Dr. A Reichenow, to the Think Parrots Show, the largest birds, to reduce the demand for wild-caught parrots, and to promote and UK parrot conference and show, and to Rosemary Low and Eric Peak for assist with parrot conservation projects. their lifetime contributions to aviculture and parrot conservation. The Think Parrots conference and show is a Parrots Magazine event. The magazine and shows have set new standards of responsibility and education for all who want to provide the best care for their birds. Whether veterinary, diet and nutrition, behaviour, training and breeding, owners are armed with the best information and valuable advice by industry experts. An eight-page report on this Show will be included in the 200th Edition of “Parrots Magazine” to be published in Sept 2014. Congratulations to John Catchpole, Publisher of one of the longest running publications on Parrots. Rosemary Low is the author of more than 20 books on parrots, including Parrots: Their Care and Breeding (three editions published in three languages), Endangered Parrots, Encyclopedia of the Lories, Why does My Parrot…?, Cockatoos in Aviculture, and Amazon Parrots. She devotes her avicultural expertise to several wild parrot conservation projects throughout the world. -

Smuggling Birds Equals Jail Time

NEWS from the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service For release July 29, 1997 Hugh Vickery 202-208-1456 SMUGGLING BIRDS EOUALS JAIL TIME FOR GADE’S I, 38 TB c()mIc- A Florida bird importer arrested as part of the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service's highly successful "Operation Renegade" has been sentenced to a year and a day in prison for illegally smuggling more than 4,000 "Congo" African grey parrots into the United States and filing false importation documents. Federal Judge Edward B. Davis also ordered Adolph "BUZZ" Pare, 63, of Miami, Florida, to pay $300,000 in fines and restitution, the largest sum ever levied against a defendant in a federal wildlife smuggling case. Pare conspired to smuggle African grey parrots, listed as a protected species under the Convention of International Trade in Endangered Species on Fauna and Flora (CITES) from Zaire to Senegal and then on to the United States. The CITES export permits falsely stated that the parrots originated in Guinea or the Ivory Coast, countries where the "Congo" African grey parrot does not occur in the wild. Pare is the 38th person to be convicted as a result of "Operation Renegade," a three-year undercover investigation by Service law enforcement agents into smuggling rings that brought exotic birds, such as parrots or macaws, or their eggs into the United States. Twenty-three of these defendants have received prison sentences totaling more than 47 years and fines totaling more than a half a million dollars. Ofice of Public Affairs 1849 C Street, hW Room 3447 Washington, DC 20240 (202)208-5634 FAX (202)219-2428 -2- Most prominently, a federal court in Chicago sentenced Tony Silva to 7 years in jail without parole and $lOO,OOb in fines in November 1996. -

~~Hr:~ Sighted Five Macaws Believed to Be Two Nestlings He Had Were Confis This Species in Flight Near Formosa Cated and Returned to Brazil

Marsh Farms INCUBATORS • FEATURING fully automatic Some Endangered Parrots turners. Adjustable temperature and humidity control. And The Role Aviculture Could Play In Their Survival by Tony Silva, Curator Loro Parque, Puerto de la Cruz Tenerife, Canary Islands The epitomy of endangered parrots locality not distant from the Sao Fran ROLL-X is a blue and grey macaw referred to cisco River where the type speci Up to 209 eggs. as Ararinha do spixi where it is men was collected. native. Ornithologists call this bird Several points highlight the history Cyanopsitta spixii and aviculturists of this macaw. Almost all sightings know it as Spix's Macaw, a species have been made in the same locality; which has no close relatives and with one exception, the person mak which is the only representative ofits ing the observations have been Ger genus. It has always been rare and at man speaking ornithologists; and the present is known from a single wild decline has been the result of trapp bird, a remnant of a population that ing, followed by habitat degradation, Up to 480 once comprised some 30 pairs. hunting and the introduction of the Egg Capacity. There are some 21 specimens in African honey bee, in that order. That captivity, and these offfer the only trapping has been the most destruc hope for saving this species from tive force is highlighted by the fact extinction. that 15 months after Roth discovered The decline ofCyanopsitta spixii is the Cura~a population, only one bird important, for it has occurred rela remained; the other two had been tively qUickly and aviculturists are collected by a dealer living in Petrol mainly to blame. -

Parrot Paul Carter

Parrot Paul Carter Animal series Parrot Animal Series editor: Jonathan Burt Already published Crow Bear Boria Sax Robert E. Bieder Ant Rat Charlotte Sleigh Jonathan Burt Tortoise Snake Peter Young Drake Stutesman Cockroach Falcon Marion Copeland Helen Macdonald Dog Bee Susan McHugh Claire Preston Oyster Rebecca Stott Forthcoming Whale Crocodile Joe Roman Richard Freeman Hare Spider Simon Carnell Katja and Sergiusz Michalski Moose Duck Kevin Jackson Victoria de Rijke Fly Salmon Steven Connor Peter Coates Tiger Wolf Susie Green Garry Marvin Fox Martin Wallen Parrot Paul Carter reaktion books Published by reaktion books ltd 33 Great Sutton Street London ec1v 0dx www.reaktionbooks.co.uk First published 2006 Copyright © Paul Carter 2006 All rights reserved No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior permission of the publishers. Printed in China British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data Carter, Paul, 1951– Parrot. – (Animal) 1. Parrots 2. Animals and civilization I. Title 595.7’1 isbn 1 86189 237 3 Contents Preface: Cage, Net, Web 7 Introduction: Communicating Parrots 10 1 Parrotics 23 2 Parroternalia 67 3 Parrotology 135 Timeline 178 Parrot Jokes 180 References 183 Bibliography 201 Associations and Websites 203 Acknowledgements 205 Photo Acknowledgements 206 Index 209 Preface: Cage, Net, Web Say ‘parrot’, and most people think they know what you mean. Writing this book, I found saying parrot was a great conversa- tion opener. It sounds like a joke, it breaks the ice, and before you know where you are, everyone has a parrot story to tell.