Religious Pluralism in the Public Square

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Chapter Legislative Recap for the 40Th Annual ESOP Conference Visit Us

July 2017 Chapter Legislative Recap for the 40th Annual ESOP Conference Company and professional members of the Minnesota / Dakotas Chapter attended numerous legislative meetings at the 40th Annual ESOP Conference in Washington, D.C., May 11 and 12. Visits were arranged where employee owners met with legislators or their respective aides to gain additional support for ESOPs. A special thank you to the legislative staff and aides at all of the MN, ND and SD congressional and senatorial offices for coordinating and participating in the meetings. We appreciate your continued support and would be interested in hosting a company visit in your district! Congresswoman Kristi Noem, North Dakota Congressman Rick Nolan, Minnesota Congressman Collin Peterson, Minnesota A New Congress with a New ESOP Bill This year on April 12, 2017, six members of congress introduced the Promotion and Expansion of Private Employee Ownership Act of 2017. Today, 14 more representatives have joined in co-sponsoring HR 2092. Thank you Co-Sponsors: Erik Paulsen, Kristi Noem, and Kevin Cramer. We would like to thank the following representatives for their support of the 2015 ESOP bills, HR. 2096 & S. 1212: Tim Walz (MN-1), Erick Paulsen (MN-3), Keith Ellison (MN-5), Tom Emmer (MN-6), Collin Peterson (MN-7), Rick Nolan (MN-8), Kevin Cramer (ND), Kristi Noem (SD), John Thune (SD), Al Franken (MN), Amy Klobuchar (MN), Heidi Heitkamp (SD) and John Hoeven (ND). Many of these representatives have been dedicated partners in supporting ESOP legislation for many years. In recognition of their consistent support, the MN/DAK ESOP Association Chapter presented Certificate of Appreciations during the Capitol Hill visits May 10 and 11th. -

Presidential Election Results

2016 Election Overview The outcome of the 2016 elections has definitely altered the landscape for transportation policy and funding initiatives. From the Presidency down to state legislative races, we face a new legislative dynamic and many new faces. What hasn’t changed: the huge need for resources to increase the nation’s and the state’s investment in the transportation system and bipartisan agreement on that fact. Prior to the outcome of Tuesday’s election we were hearing from candidates on both sides of the aisle that increasing investments in infrastructure was an area of agreement. Candidates for Minnesota’s legislature brought up the need for a comprehensive, long-term transportation funding package over and over again in news stories, candidate profiles and candidate forums. We were hearing more from candidates about transportation than we have in previous election cycles. Voters in other states, made their voices heard by approving ballot initiatives in 22 states that increased and stabilized funding for transportation. As we head into 2017, transportation advocates have a huge opportunity to capitalize on the widespread support for infrastructure improvements. However, it will take the involvement of transportation advocates across the state making their voices heard to rise above partisan squabbling and the many other issues that will be on the table. National Presidential Election Results Electoral Votes Needed to Win: 270 *Remaining: 16 Trump (R) Electoral Votes 290 Popular Vote 60,375,961 Clinton (D) Electoral Votes 232 Popular Vote 61,047,207 Minnesota Clinton (D) percent 46.9% votes 1,366,676 Trump (R) percent 45.4% votes 1,322,891 The race for the White House defied the polls and expectations as Donald Trump won more than the needed 270 votes in the electoral college while Hillary Clinton narrowly won the popular vote. -

2011 Legislative and Congressional Districts

! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! 2011 Minnesota House and Senate Membership ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! A Rep. Dan Fabian-(R) A Rep. Steve Gottwalt-(R) A Rep. Duane Quam-(R) A Rep. Sarah Anderson-(R) A Rep. John Kriesel-(R) B Rep. Deb Kiel-(R) B Rep. King Banaian-(R) B Rep. Kim Norton-(DFL) B Rep. John Benson-(DFL) B Rep. Denny McNamara-(R) Sen. LeRoy A. Stumpf-(DFL) Sen. John Pederson-(R) Sen. David Senjem-(R) Sen. Terri Bonoff-(DFL) Sen. Katie Sieben-(DFL) ! 1 15 29 43 57 A Rep. Kent Eken-(DFL) A Rep. Sondra Erickson-(R) A Rep. Tina Liebling-(DFL) A Rep. Steve Simon-(DFL) A Rep. Joe Mullery-(DFL) B Rep. David Hancock-(R) B Rep. Mary Kiffmeyer-(R) B Rep. Mike Benson-(R) B Rep. Ryan Winkler-(DFL) B Rep. Bobby Joe Champion-(DFL) Sen. Rod Skoe-(DFL) Sen. Dave Brown-(R) Sen. Carla Nelson-(R) Sen. Ron Latz-(DFL) Sen. Linda Higgins-(DFL) 2 16 30 44 58 ! A Rep. Tom Anzelc-(DFL) A Rep. Kurt Daudt-(R) A Rep. Gene Pelowski Jr.-(DFL) A Rep. Sandra Peterson-(DFL) A Rep. Diane Loeffler-(DFL) B Rep. Carolyn McElfatrick-(R) B Rep. Bob Barrett-(R) B Rep. Gregory Davids-(R) B Rep. Lyndon Carlson-(DFL) B Rep. Phyllis Kahn-(DFL) ! ! ! Sen. Tom Saxhaug-(DFL) Sen. Sean Nienow-(R) Sen. Jeremy Miller-(R) Sen. Ann H. Rest-(DFL) Sen. Lawrence Pogemiller-(DFL) 2011 Legislati! ve and Congressional Districts 3 17 31 45 59 A Rep. John Persell-(DFL) A Rep. Ron Shimanski-(R) A Rep. Joyce Peppin-(R) A Rep. Michael Nelson-(DFL) A Rep. -

General Keith Ellison Helplng People Afford Their Lives and Live with Dignity and Respect

27-CR-20-12951 Filed in District Court State of Minnesota 5/21/2021 3:11 PM .. The Office of " Minnesota Attorney General Keith Ellison helplng people afford their lives and live with dignity and respect - www.ag.state.mn.us February 19, 2021 The Honorable Peter A. Cahill Hennepin County Courthouse 300 Sixth Street South Minneapolis, MN 55487 Re: State v. Chauvin, Kueng, Lane, and Thao Court File No. 27-CR-20-12646, 27-CR-20-12953, 27-CR—20-12951, 27-CR-20-12646 Dear Judge Cahill: I made no contribution of any kind to the recent New York Times article (dated 2/10/21) in which the reporter asserts that Derek Chauvin was willing to plead guilty to third degree murder in state court in exchange for an agreement of non-prosecution for federal criminal charges. No one on our prosecution team contributed to the New York Times report of an alleged plea deal by Chauvin or the alleged involvement of the then-US. Attorney General. Defense counsel’s allegations are simply not true. We are mindful of our responsibilities under Rules 3.8 and 3.3 of the Minnesota Rules of Professional Conduct. I conducted a quick internet search of news articles about this alleged plea negotiation. It turns out that these alleged plea negotiations are hardly news at all. I found the following stories below, with relevant excerpts: Fox 9: Eli-Minneapolis police officer Chauvin was in talks to plead gum before arrest |June 9, 202M At the time, Chauvin was represented by Tom Kelly, who declined to comment. -

Missouri Voting and Elections 597

CHAPTER 7 MISSOURI ELECTIONS Vice President Harry S Truman preparing to take oath of offi ce. Harry S Truman Library and Museum 596 OFFICIAL MANUAL When do Missourians vote? In addition to certain special and emergency dates, there are fi ve offi cial election dates in Mis- Missouri Voting souri: State law requires that all public elections be held on the general election day, the primary and Elections election day, the general municipal election day, the fi rst Tuesday after the fi rst Monday in Novem- Who registers to vote in Missouri? ber, or on another day expressly provided by city or county charter. In nonprimary years, an elec- Citizens living in Missouri must register in tion may be held on the fi rst Tuesday after the fi rst order to vote. Any U.S. citizen 17 years and 6 months of age or older, if a Missouri resident, Monday in August. (RSMo 115.123.1) may register to vote in any election held on or The general election day is the fi rst Tuesday after his/her 18th birthday, except: after the fi rst Monday in November in even-num- • A person who is adjudged incapacitated. bered years. The primary election day is the fi rst Tuesday after the fi rst Monday in August in even- • A person who is confi ned under sentence numbered years. (RSMo 115.121.1 and .2) of imprisonment. Elections for cities, towns, villages, school • A person who is on probation or parole boards and special district offi cers are held the after conviction of a felony until fi nally dis- fi rst Tuesday after fi rst Monday in April each charged. -

FY 2006 from the Dod Iraq Freedom Fund Account To: Reimburse Foreign Governments and Train Foreign Government Military A

06-F-00001 B., Brian - 9/26/2005 10/18/2005 Request all documents pertaining to the Cetacean Intelligence Mission. 06-F-00002 Poore, Jesse - 9/29/2005 11/9/2005 Requesting for documents detailing the total amount of military ordanence expended in other countries between the years of 1970 and 2005. 06-F-00003 Allen, W. - 9/27/2005 - Requesting the signed or unsigned document prepared for the signature of the Chairman, JCS, that requires the members of the armed forces to provide and tell the where abouts of the most wanted Ben Laden. Document 06-F-00004 Ravenscroft, Michele - 9/16/2005 10/6/2005 Request the contracts that have been awarded in the past 3 months to companies with 5000 employees or less. 06-F-00005 Elia, Jacob - 9/29/2005 10/6/2005 Letter is Illegable. 06-F-00006 Boyle Johnston, Amy - 9/28/2005 10/4/2005 Request all documents relating to a Pentagon "Politico-Military" # I- 62. 06-F-00007 Ching, Jennifer Gibbons, Del Deo, Dolan, 10/3/2005 - Referral of documents responsive to ACLU litigation. DIA has referred 21 documents Griffinger & Vecchinone which contain information related to the iraqi Survey Group. Review and return documents to DIA. 06-F-00008 Ching, Jennifer Gibbons, Del Deo, Dolan, 10/3/2005 - Referral of documents responsive to ACLU litigation. DIA has referred three documents: Griffinger & Vecchinone V=322, V=323, V=355, for review and response back to DIA. 06-F-00009 Ravnitzky, Michael - 9/30/2005 10/17/2005 NRO has identified two additional records responsive to a FOIA appeal from Michael Ravnitzky. -

Obama Leads in Both VA and NC

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE July 10, 2012 INTERVIEWS: Tom Jensen 919-744-6312 IF YOU HAVE BASIC METHODOLOGICAL QUESTIONS, PLEASE E-MAIL [email protected], OR CONSULT THE FINAL PARAGRAPH OF THE PRESS RELEASE Obama leads in both VA and NC Raleigh, N.C. – For all the twists and turns of his presidency and his re-election campaign so far, President Obama finds himself in very similar shape in two states he surprised the world by winning four years ago as he was then. Obama has retaken a narrow lead in North Carolina a month after having ceded his edge over Mitt Romney for the first time since last October. In early June, PPP showed Romney with a two-point edge in the crucial Tar Heel State (48-46). But now Obama leads by one point (47-46) in a state he took by less than a point four years ago. Meanwhile, Obama is up eight points in N.C.’s northern neighbor Virginia (50-42). He topped Romney by an identical margin when PPP last polled the Old Dominion in April (51-43), and beat John McCain by only six points there. This slight regression in Romney’s fortunes in North Carolina comes as the Obama campaign has hit the Republican candidate repeatedly over his tenure at Bain Capital. 40% of Tar Heel voters say what they know of Romney’s time there makes them feel more negatively about him, with only 29% saying it makes them more positive toward him. 27% say Romney’s Bain record makes no difference to them. -

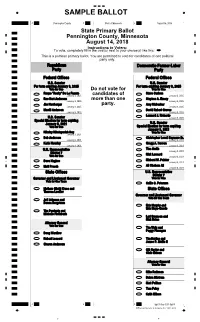

Sample Ballot

SAMPLE BALLOT A Pennington CountyB State of MinnesotaC August 14, 2018 State Primary Ballot Pennington County, Minnesota August 14, 2018 Instructions to Voters: To vote, completely fill in the oval(s) next to your choice(s) like this: R This is a partisan primary ballot. You are permitted to vote for candidates of one political party only. Republican Democratic-Farmer-Labor Party Party Federal Offices Federal Offices U.S. Senator U.S. Senator For term expiring January 3, 2025 For term expiring January 3, 2025 Vote for One Do not vote for Vote for One Roque "Rocky" De La Fuente Steve Carlson January 3, 2025 candidates of January 3, 2025 Rae Hart Anderson more than one Stephen A. Emery January 3, 2025 January 3, 2025 Jim Newberger party. Amy Klobuchar January 3, 2025 January 3, 2025 Merrill Anderson David Robert Groves January 3, 2025 January 3, 2025 Leonard J. Richards U.S. Senator January 3, 2025 Special Election for term expiring January 3, 2021 U.S. Senator Vote for One Special Election for term expiring January 3, 2021 Nikolay Nikolayevich Bey Vote for One January 3, 2021 Bob Anderson Christopher Lovell Seymore Sr. January 3, 2021 January 3, 2021 Karin Housley Gregg A. Iverson January 3, 2021 January 3, 2021 Tina Smith U.S. Representative January 3, 2021 District 7 Nick Leonard Vote for One January 3, 2021 Richard W. Painter Dave Hughes January 3, 2021 Ali Chehem Ali Matt Prosch January 3, 2021 State Offices U.S. Representative District 7 Governor and Lieutenant Governor Vote for One Vote for One Team Collin C. -

NRCC: MN-07 “Vegas, Baby”

NRCC: MN-07 “Vegas, Baby” Script Documentation AUDIO: Taxpayers pay for Colin Peterson’s Since 1991, Peterson Has Been Reimbursed At personal, private airplane when he’s in Minnesota. Least $280,000 For Plane Mileage. (Statement of Disbursements of House, Chief Administrative Officer, U.S. House of Representatives) (Receipts and Expenditures: Report of the Clerk of TEXT: Collin Peterson the House, U.S. House of Representatives) Taxpayers pay for Peterson’s private plane Statement of Disbursements of House AUDIO: But do you know where else he’s going? Peterson Went Las Vegas On Trip Sponsored By The Safari Club International From March AUDIO: That’s right. Vegas, Baby. Vegas. 22, 2002 To March 25, 2002 Costing, $1,614. (Collin Peterson, Legistorm, Accessed 3/17/14) Peterson Went Las Vegas On Trip Sponsored By The American Federation Of Musicians From June 23, 2001 To June 25, 2001, Costing $919. (Collin Peterson, Legistorm, Accessed 3/17/14) Peterson Went Las Vegas On Trip Sponsored By The Safari Club International From January 11, 2001 To January 14, 2001, Costing $918.33. (Collin Peterson, Legistorm, Accessed 3/17/14) AUDIO: Colin Peterson took 36 junkets. Vacation- Throughout His Time In Congress, Peterson like trips, paid for by special interest groups. Has Taken At Least 36 Privately Funded Trip Worth $57,942 (Collin Peterson, Legistorm, Accessed 3/17/14) TEXT: 36 Junkets paid for by special interest groups See backup below Legistorm AUDIO: In Washington, Peterson took $6 million in Collin Peterson Took $6.7 Million In Campaign campaign money from lobbyists and special Money From Special Interest Group PACs interests. -

Spring 2009 U.S

Nonprofit Org. SPRING 2009 U.S. Postage IN THIS ISSUE PAID S P R I N G 2 0 0 9 N225 Mondale Hall Visits from Clarence Thomas, Guido Calabresi, Nadine Strossen • Summer CLE • Clarence Darrow Collection 229 19th Avenue South Minneapolis, MN Minneapolis, MN 55455 Permit No. 155 8 Perspectives > THOMAS , CALABRESI , STROSSEN VISITS 40 • CLE • DARROW COLLECTION 6 36 22 46 Training a Global Workforce An expanding education for a shrinking world 41 13 www.law.umn.edu 17 4 Update on Partners in Excellence Annual Fund Dear Law School Alumni: As National Chair of this year’s Partners in Excellence annual fund drive, I have had the privilege of observing the generosity of some very dedicated Law School alumni stewards. Despite what we have come to know as “these tough economic times,” many of you have stepped DEAN ALUMNI BOARD forward to put us on pace to achieve two significant milestones for this David Wippman year's campaign: $1 million and 23% alumni participation. Term ending 2009 DIRECTOR OF COMMUNICATIONS James Bender (’81) A record annual fund campaign is more than just a goal: It will enable Cynthia Huff Elizabeth Bransdorfer (’85) (Secretary) the Law School to recruit the best students and retain the best faculty. Judge Natalie Hudson (’82) I want particularly to acknowledge the generosity of this year’s Fraser SENIOR EDITOR AND WRITER Chuck Noerenberg (’82) Scholars Society and Dean’s Circle donors (through April 1, 2009): Corrine Charais Judith Oakes (’69) Patricia O’Gorman (’71) DIRECTOR OF ALUMNI RELATIONS AND ANNUAL GIVING Term ending 2010 > Fraser Scholars Society > Dean’s Circle Anita C. -

MINNESOTA CONVICTION REVIEW UNIT CHARTER As One of Attorney

MINNESOTA CONVICTION REVIEW UNIT CHARTER As one of Attorney General Keith Ellison's criminal justice reform initiatives,1 the Office of the Minnesota Attorney General, in conjunction with a federal grant received by the Great North Innocence Project, has created and will implement and direct a statewide Conviction Review Unit (CRU) to conduct extrajudicial review of juvenile adjudications, criminal convictions, and sentences2 in cases with plausible allegations of actual innocence or manifest injustice. The CRU shall conduct strategically collaborative, good-faith case reviews to ensure the integrity of challenged convictions, remedy wrongful convictions, and take any remedial measures necessary to correct injustices uncovered, within the bounds of the law. In cases where the CRU concludes there was a wrongful conviction—where the person convicted did not commit the crime—the CRU will seek to identify the true perpetrator of the underlying crime(s). The CRU will also study and collect data on the causes of wrongful convictions in Minnesota, in service of informing statewide policies and procedures designed to prevent such injustices going forward and strengthen community confidence in the criminal legal system overall. The CRU is committed to seeking the truth, communicating with and respecting crime victims, and ensuring transparency in the review process and shall openly and regularly report its case review numbers to the public. To fulfill its mission, the CRU will operate independently from trial, appellate, and post-conviction litigation units in the office, and will, where possible, conduct joint or cooperative investigations with applicants’ counsel, and, where joint investigation is not feasible, will approach its review and investigation in a non-adversarial manner, always with the goal of ensuring that justice prevails in each and every case. -

Freshman Class of the 110Th Congress at a Glance

Freshman Class of the 110th Congress at a Glance NEW HOUSE MEMBERS BY DISTRICT Position on Position on District Republican Democrat1 Winner Immigration Immigration Border security with AZ-05 J.D. Hayworth Enforcement first Harry E. Mitchell Mitchell • guest worker program Employer sanctions; Randy Graf AZ-08 Enforcement first Gabrielle Giffords “comprehensive Giffords (Jim Kolbe) reform” “Comprehensive CA-11 Richard W. Pombo• Enforcement first Jerry McNerney reform” and “path to McNerney citizenship” Kevin McCarthy Enforcement and tighter CA-22 Sharon M. Beery No clear position McCarthy (Bill Thomas) border security Doug Lamborn Tighter security; CO-05 Jay Fawcett Enforcement first Lamborn (Joel Hefley) opposes amnesty “Comprehensive Rick O’Donnell Enforcement first; CO-07 Ed Perlmutter reform” and “path to Perlmutter (Bob Beauprez) employer sanctions citizenship” CT-02 Bob Simmons• Enforcement first Joe Courtney Employer Sanctions Courtney Supports tighter border CT-05 Nancy L. Johnson Christopher S. Murphy “Path to citizenship” Murphy • security 1For simplification, this column also includes Independents. Incumbent Retiring incumbent Vacating to run for higher office Resigning Lost in the primary Position on Position on District Republican Democrat1 Winner Immigration Immigration Gus Bilirakis FL-09 Enforcement first Phyllis Busansky Supports border security Bilirakis (Michael Bilirakis) Kathy Castor “Comprehensive FL-11 Eddie Adams Opposes amnesty Castor (Jim Davis) reform” Supports enforcement, Vern Buchanan Employer sanctions; FL-13 tighter security; Christine Jennings Buchanan (Katherine Harris) “path to citizenship” opposes amnesty Supports border Joe Negron FL-16 Tighter border security Tim Mahoney security; “path to Mahoney (Mark Foley) citizenship” “Comprehensive reform”; FL-22 E. Clay Shaw Ron Klein Employer sanctions Klein • guest worker program Hank Johnson “Comprehensive GA-04 Catherine Davis Enforcement first; removal (Cynthia A.