Joseph Joachim

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Joachim Raff Symphony No

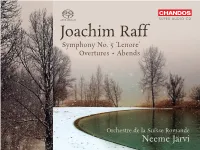

SUPER AUDIO CD Joachim Raff Symphony No. 5 ‘Lenore’ Overtures • Abends Orchestre de la Suisse Romande Neeme Järvi © Mary Evans Picture Library Picture © Mary Evans Joachim Raff Joachim Raff (1822 – 1882) 1 Overture to ‘Dame Kobold’, Op. 154 (1869) 6:48 Comic Opera in Three Acts Allegro – Andante – Tempo I – Poco più mosso 2 Abends, Op. 163b (1874) 5:21 Rhapsody Orchestration by the composer of the fifth movement from Piano Suite No. 6, Op. 163 (1871) Moderato – Un poco agitato – Tempo I 3 Overture to ‘König Alfred’, WoO 14 (1848 – 49) 13:43 Grand Heroic Opera in Four Acts Andante maestoso – Doppio movimento, Allegro – Meno moto, quasi Marcia – Più moto, quasi Tempo I – Meno moto, quasi Marcia – Più moto – Andante maestoso 4 Prelude to ‘Dornröschen’, WoO 19 (1855) 6:06 Fairy Tale Epic in Four Parts Mäßig bewegt 5 Overture to ‘Die Eifersüchtigen’, WoO 54 (1881 – 82) 8:25 Comic Opera in Three Acts Andante – Allegro 3 Symphony No. 5, Op. 177 ‘Lenore’ (1872) 39:53 in E major • in E-Dur • en mi majeur Erste Abtheilung. Liebesglück (First Section. Joy of Love) 6 Allegro 10:29 7 Andante quasi Larghetto 8:04 Zweite Abtheilung. Trennung (Second Section. Separation) 8 Marsch-Tempo – Agitato 9:13 Dritte Abtheilung. Wiedervereinigung im Tode (Third Section. Reunion in Death) 9 Introduction und Ballade (nach G. Bürger’s ‘Lenore’). Allegro – Un poco più mosso (quasi stretto) 11:53 TT 80:55 Orchestre de la Suisse Romande Bogdan Zvoristeanu concert master Neeme Järvi 4 Raff: Symphony No. 5 ‘Lenore’ / Overtures / Abends Symphony No. 5 in E major, Op. -

Annual Report 2004 > >

Annual Report 2004 >> Living space . > > Contents Letter from the Board of Management >> 4 Private Customer Business Sector >> 6 Contents Commercial Lending Business >> 8 > Management Report >> 12 Balance Sheet >> 26 Income Statement >> 30 General Information on Accounting Policies >> 34 Report of the Supervisory Board >> 47 Members of the Delegates Meeting >> 50 Contact >> 52 Imprint >> 54 Dear shareholders and business associates, 4 > > Friedrich Munsberg, Erich Rödel, Dr. Bernhard Scholz (from left) The situation in the banking sector improved The Münchener Hypothekenbank was also slightly during the past year. Although provisions affected by these developments – albeit to a made for risks continued to put pressure on lesser extent than seen among its peers. In results, unrelenting cuts in personnel levels comparison to the previous year’s figures, the began to have an effect on costs. The banks’ Bank’s provisions for risks have already passed performance reflected a weak willingness to their high point. invest and the overall sluggish economic con- ditions in Germany. It would be more than naive to solely ascribe these developments to the unfavourable economic These developments also impacted on the environment and then stake our hopes for the MünchenerHyp in 2004. Our new commitments future on a business upswing that could lead for mortgages declined by about seven percent to improved earnings in the near future: Letter from the Board of Management to barely EUR 1.5 billion. However, in comparison with the entire mortgage banking industry, this >> The highly intensive competitive situation, > decline was relatively small. Nevertheless, our and ongoing efforts to further automate 4 performance remained unsatisfactory as our the standard processes in the lending results from operations contracted to EUR 16.8 business, will not permit a sustainable 200 million and net income fell to EUR 8.3 million. -

97679 Digibooklet Schumann Vol

ROBERT SCHUMANN Complete Symphonic Works VOL. III OREN SHEVLIN WDR Sinfonieorchester Köln HEINZ HOLLIGER ROBERT SCHUMANN Complete Symphonic Works • Vol. III recording date: April 8-11, 2013 Cello Concerto in A minor, Op. 129 23:59 I. Nicht zu schnell 11:51 II. Langsam 4:08 P Eine Produktion des Westdeutschen Rundfunks Köln, 2013 lizenziert durch die WDR mediagroup GmbH III. Sehr lebhaft 8:00 recording location: Köln, Philharmonie executive producer (WDR): Siegwald Bütow recording producer & editing: Günther Wollersheim Symphony No. 4 in D minor, Op. 120 recording engineer: Brigitte Angerhausen (revised version 1851) 28:56 Recording assistant: Astrid Großmann I. Ziemlich langsam. Lebhaft 10:25 photos: Oren Shevlin (page 8): Neda Navaee II. Romanze. Ziemlich langsam 3:57 Heinz Holliger (page 10): Julieta Schildknecht III. Scherzo. Lebhaft 6:45 WDR Sinfonieorchester Köln (page 5): WDR Thomas Kost IV. Langsam. Lebhaft 7:49 WDR Sinfonieorchester Köln (page 9): Mischa Salevic front illustration: ‘Mondaufgang am Meer’ Caspar David Friedrich art direction and design: AB•Design executive producer (audite): Dipl.-Tonmeister Ludger Böckenhoff OREN SHEVLIN e-mail: [email protected] • http: //www.audite.de WDR Sinfonieorchester Köln © 2014 Ludger Böckenhoff HEINZ HOLLIGER Remembering, Narrating Schumann’s Cello Concerto contains movements are recalled in the same way the same in another: only the material is On 2 September 1848 Robert Schumann many recollections of Mendelssohn. It as Beethoven had done in his Ninth Sym- different”. Schumann noted this maxim no composed a piece for piano and called opens with three wind chords similar phony. Schumann also referred to his own later than 1834, at the age of twenty-four, it Erinnerung [recollection], inserting to those in the overtures to A Midsum- works: in the transition from the fi rst to the and he followed it in his ideal of musical the subtitle “4. -

The University of Chicago Objects of Veneration

THE UNIVERSITY OF CHICAGO OBJECTS OF VENERATION: MUSIC AND MATERIALITY IN THE COMPOSER-CULTS OF GERMANY AND AUSTRIA, 1870-1930 A DISSERTATION SUBMITTED TO THE FACULTY OF THE DIVISION OF THE HUMANITIES IN CANDIDACY FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY DEPARTMENT OF MUSIC BY ABIGAIL FINE CHICAGO, ILLINOIS AUGUST 2017 © Copyright Abigail Fine 2017 All rights reserved ii TABLE OF CONTENTS LIST OF MUSICAL EXAMPLES.................................................................. v LIST OF FIGURES.......................................................................................... vi LIST OF TABLES............................................................................................ ix ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS............................................................................. x ABSTRACT....................................................................................................... xiii INTRODUCTION........................................................................................................ 1 CHAPTER 1: Beethoven’s Death and the Physiognomy of Late Style Introduction..................................................................................................... 41 Part I: Material Reception Beethoven’s (Death) Mask............................................................................. 50 The Cult of the Face........................................................................................ 67 Part II: Musical Reception Musical Physiognomies............................................................................... -

Cash Transfers and Child Schooling

WPS6340 Policy Research Working Paper 6340 Public Disclosure Authorized Impact Evaluation Series No. 82 Cash Transfers and Child Schooling Evidence from a Randomized Evaluation Public Disclosure Authorized of the Role of Conditionality Richard Akresh Damien de Walque Harounan Kazianga Public Disclosure Authorized The World Bank Public Disclosure Authorized Development Research Group Human Development and Public Services Team January 2013 Policy Research Working Paper 6340 Abstract The authors conduct a randomized experiment in rural children who are traditionally favored by parents for Burkina Faso to estimate the impact of alternative cash school participation, including boys, older children, and transfer delivery mechanisms on education. The two- higher ability children. However, the conditional transfers year pilot program randomly distributed cash transfers are significantly more effective than the unconditional that were either conditional or unconditional. Families transfers in improving the enrollment of “marginal under the conditional schemes were required to have children” who are initially less likely to go to school, such their children ages 7–15 enrolled in school and attending as girls, younger children, and lower ability children. classes regularly. There were no such requirements under Thus, conditionality plays a critical role in benefiting the unconditional programs. The results indicate that children who are less likely to receive investments from unconditional and conditional cash transfer programs their parents. have a similar impact increasing the enrollment of This paper is a product of the Human Development and Public Services Team, Development Research Group. It is part of a larger effort by the World Bank to provide open access to its research and make a contribution to development policy discussions around the world. -

Brahms Reimagined by René Spencer Saller

CONCERT PROGRAM Friday, October 28, 2016 at 10:30AM Saturday, October 29, 2016 at 8:00PM Jun Märkl, conductor Jeremy Denk, piano LISZT Prometheus (1850) (1811–1886) MOZART Piano Concerto No. 23 in A major, K. 488 (1786) (1756–1791) Allegro Adagio Allegro assai Jeremy Denk, piano INTERMISSION BRAHMS/orch. Schoenberg Piano Quartet in G minor, op. 25 (1861/1937) (1833–1897)/(1874–1951) Allegro Intermezzo: Allegro, ma non troppo Andante con moto Rondo alla zingarese: Presto 23 ACKNOWLEDGMENTS These concerts are part of the Wells Fargo Advisors Orchestral Series. Jun Märkl is the Ann and Lee Liberman Guest Artist. Jeremy Denk is the Ann and Paul Lux Guest Artist. The concert of Saturday, October 29, is underwritten in part by a generous gift from Lawrence and Cheryl Katzenstein. Pre-Concert Conversations are sponsored by Washington University Physicians. Large print program notes are available through the generosity of The Delmar Gardens Family, and are located at the Customer Service table in the foyer. 24 CONCERT CALENDAR For tickets call 314-534-1700, visit stlsymphony.org, or use the free STL Symphony mobile app available for iOS and Android. TCHAIKOVSKY 5: Fri, Nov 4, 8:00pm | Sat, Nov 5, 8:00pm Han-Na Chang, conductor; Jan Mráček, violin GLINKA Ruslan und Lyudmila Overture PROKOFIEV Violin Concerto No. 1 I M E TCHAIKOVSKY Symphony No. 5 AND OCK R HEILA S Han-Na Chang SLATKIN CONDUCTS PORGY & BESS: Fri, Nov 11, 10:30am | Sat, Nov 12, 8:00pm Sun, Nov 13, 3:00pm Leonard Slatkin, conductor; Olga Kern, piano SLATKIN Kinah BARBER Piano Concerto H S ODI C COPLAND Billy the Kid Suite YBELLE GERSHWIN/arr. -

From English to Code-Switching: Transfer Learning with Strong Morphological Clues

From English to Code-Switching: Transfer Learning with Strong Morphological Clues Gustavo Aguilar and Thamar Solorio Department of Computer Science University of Houston Houston, TX 77204-3010 fgaguilaralas, [email protected] Abstract Hindi-English Tweet Original: Keep calm and keep kaam se kaam !!!other #office Linguistic Code-switching (CS) is still an un- #tgif #nametag #buddhane #SouvenirFromManali #keepcalm derstudied phenomenon in natural language English: Keep calm and mind your own business !!! processing. The NLP community has mostly focused on monolingual and multi-lingual sce- Nepali-English Tweet narios, but little attention has been given to CS Original: Youtubene ma live re ,other chalcha ki vanni aash in particular. This is partly because of the lack garam !other Optimistic .other of resources and annotated data, despite its in- English: They said Youtube live, let’s hope it works! Optimistic. creasing occurrence in social media platforms. Spanish-English Tweet In this paper, we aim at adapting monolin- Original: @MROlvera06 @T11gRe go too gual models to code-switched text in various other other cavenders y tambien ve a @ElToroBoots tasks. Specifically, we transfer English knowl- ne ne other English: @MROlvera06 @T11gRe go to cavenders and edge from a pre-trained ELMo model to differ- also go to @ElToroBoots ent code-switched language pairs (i.e., Nepali- English, Spanish-English, and Hindi-English) Figure 1: Examples of code-switched tweets and using the task of language identification. Our their translations from the CS LID corpora for Hindi- method, CS-ELMo, is an extension of ELMo English, Nepali-English and Spanish-English. The LID with a simple yet effective position-aware at- labels ne and other in subscripts refer to named enti- tention mechanism inside its character convo- ties and punctuation, emojis or usernames, respectively lutions. -

Historie Der Rheinischen Musikschule Teil 1 Mit Einem Beitrag Von Professor Heinrich Lindlahr

Historie der Rheinischen Musikschule Teil 1 Mit einem Beitrag von Professor Heinrich Lindlahr Zur Geschichte des Musikschulwesens in Köln 1815 - 1925 Zu Beginn des musikfreundlichen 19. Jahrhunderts blieb es in Köln bei hochfliegenden Plänen und deren erfolgreicher Verhinderung. 1815, Köln zählte etwa fünfundzwanzigtausend Seelen, die soeben, wie die Bewohner der Rheinprovinz insgesamt, beim Wiener Kongreß an das Königreich Preußen gefallen waren, 1815 also hatte von Köln aus ein ungenannter Musikenthusiast für die Rheinmetropole eine Ausbildungsstätte nach dem Vorbild des Conservatoire de Paris gefordert. Sein Vorschlag erschien in der von Friedrich Rochlitz herausgegebenen führenden Allgemeinen musikalischen Zeitung zu Leipzig. Doch Aufrufe solcher Art verloren sich hierorts, obschon Ansätze zu einem brauchbaren Musikschulgebilde in Köln bereits bestanden hatten: einmal in Gestalt eines Konservatorienplanes, wie ihn der neue Maire der vormaligen Reichstadt, Herr von VVittgenstein, aus eingezogenen kirchlichen Stiftungen in Vorschlag gebracht hatte, vorwiegend aus Restklassen von Sing- und Kapellschulen an St. Gereon, an St. Aposteln, bei den Ursulinen und anderswo mehr, zum anderen in Gestalt von Heimkursen und Familienkonzerten, wie sie der seit dem Einzug der Franzosen, 1794, stellenlos gewordene Salzmüdder und Domkapellmeister Dr. jur. Bernhard Joseph Mäurer führte. Unklar blieb indessen, ob sich der Zusammenschluss zu einem Gesamtprojekt nach den Vorstellungen Dr. Mäurers oder des Herrn von Wittgenstein oder auch jenes Anonymus deshalb zerschlug, weil die Durchführung von Domkonzerten an Sonn- und Feiertagen kirchenfremden und besatzungsfreundlichen Lehrkräften hätte zufallen sollen, oder mehr noch deshalb, weil es nach wie vor ein nicht überschaubares Hindernisrennen rivalisierender Musikparteien gab, deren manche nach Privatabsichten berechnet werden müssten, wie es die Leipziger Allgemeine musikalische Zeitung von 1815 lakonisch zu kommentieren wusste. -

Robert Schumann on the Poems of Heinrich Heine

DICHTERLIEBE opus 48 A Cycle of Sixteen. Songs by Robert Schumann on the poems of Heinrich Heine An Honors Thesis (Honrs 499) by Shawn L. Harrington Thesis Advisor (u,r$/ Mr. John Meadows", . " (! jl'lrli{Lul ~t;(,cY\' Ball State University Muncie, Indiana November, 1995 Expected date of graduation 12/95 !J,:'( ! __ <l !.", .,.' , j:L. ' .. " Purpose of Thesis This project has two components: a written discussion of the music of the Dichterliebe, and the lives of the composer Robert Schumann and the poet Heinrich Heine; and an audio tape of my performance of the Dichterliebe. The performance was the culmination of my study of the Dichterliebe, in particular, and of my voice studies, in general. Through the performance, I set out to share the wonderful music and poetry of the Dichterliebe as well as share my musical and vocal growth over the past four years. The written portion of the project was undertaken to satisfy my personal curiosity of the men who wrote the music and the poetry of the Dichterliebe. A study of the music without knowing the man who composed it or the man who wrote the words would be only half complete at best. Likewise, a study of the men and not the music would also be incomplete. That is why I included both venues of learning and experiencing in this project; and that is why I have included an audio tape of the performance with this written report. Acknowledgements I would like to thank my voice instructor (and thesis advisor), John Meadows. Without his expertise, advise, and instruction, I would not have been able to present the Dichterliebe in a performance. -

The Nineteenth Century, Part 2: Nationalism and Ideology

A-R Online Music Anthology www.armusicanthology.com Content Guide The Nineteenth Century, Part 2: Nationalism and Ideology Joseph E. Jones is Associate Professor at Texas A&M by Joseph E. Jones and Sarah Marie Lucas University-Kingsville. His research has focused on German opera, especially the collaborations of Strauss Texas A&M University-Kingsville and Hofmannsthal, and Viennese cultural history. He co- edited Richard Strauss in Context (Cambridge, 2020) Assigned Readings and directs a study abroad program in Austria. Core Survey Sarah Marie Lucas is Lecturer of Music History, Music Historical and Analytical Perspectives Theory, and Ear Training at Texas A&M University- Composer Biographies Kingsville. Her research interests include reception and Supplementary Readings performance history, as well as sketch studies, particularly relating to Béla Bartók and his Summary List collaborations with the conductor Fritz Reiner. Her work at the Budapest Bartók Archives was supported by a Genres to Understand Fulbright grant. Musical Terms to Understand Contextual Terms, Figures, and Events Main Concepts Scores and Recordings Exercises This document is for authorized use only. Unauthorized copying or posting is an infringement of copyright. If you have questions about using this guide, please contact us: http://www.armusicanthology.com/anthology/Contact.aspx Content Guide: The Nineteenth Century, Part 2 (Nationalism and Ideology) 1 ______________________________________________________________________________ Content Guide The Nineteenth Century, -

SLUB Dresden Erwirbt Korrespondenzen Von Clara Schumann Und Johannes Brahms Mit Ernst Rudorff

Berlin, 24. Juni 2021 SLUB Dresden erwirbt Korrespondenzen von Clara Schumann und Johannes Brahms mit Ernst Rudorff Die Sächsische Landesbibliothek – Staats- und Universitätsbibliothek Dresden (SLUB Dresden) erwirbt Korrespondenzen von Clara Schumann (1819-1896) und Johannes Brahms (1833-1897) jeweils mit dem Berliner Dirigenten Ernst Rudorff (1840-1916). Die Korrespondenzen waren bislang für die Wissenschaft unzugänglich. Die Kulturstiftung der Länder fördert den Ankauf mit 42.500 Euro. Dazu Prof. Dr. Markus Hilgert, Generalsekretär der Kulturstiftung der Länder: „Die Botschaft, dass diese mehr als 400 Schriftstücke, die zuvor in Privatbesitz waren, nun erstmals der Öffentlichkeit und der Wissenschaft zugänglich sind – jetzt bereits online verfügbar auf der Webseite der SLUB Dresden –, dürfte zahlreiche Musikwissenschaftlerinnen und Musikwissenschaftler aus der ganzen Welt dorthin locken. Die wertvollen Korrespondenzen sind nicht nur Zeugnisse von Clara Schumanns ausgedehnter Konzerttätigkeit quer durch den Kontinent. Sie sind auch Dokumente einer Musikepoche und bieten Einblicke in die Musikwelt Europas zwischen 1858 und 1896.“ Eigenhändiger Brief Clara Schumann an Ernst Rudorff, Moskau und Petersburg, April/Mai 1864, SLUB Dresden, Mscr.Dresd.App. 3222A,19 u. 20; Foto: © SLUB Dresden/Ramona Ahlers-Bergner Die Korrespondenzen zwischen Clara Schumann und Ernst Rudorff umfassen 215 handschriftliche Briefe der Pianistin und 170 Briefe ihres einstigen Schülers. Der Briefwechsel zwischen Brahms und Rudorff besteht aus 16 Briefen von Brahms und zwölf Gegenbriefen von Rudorff sowie ein Blatt mit Noten, beschrieben von beiden. Beide Briefwechsel wurden in das niedersächsische Verzeichnis national wertvollen Kulturgutes aufgenommen. Rund sechs Jahre (1844-1850) wohnte Clara Schumann gemeinsam mit ihrem Mann in Dresden. Die angekauften Korrespondenzen Schumanns mit Rudorff beginnen 1858 und enden mit bis dahin hoher Regelmäßigkeit im Jahr ihres Todes, 1896. -

City Research Online

City Research Online City, University of London Institutional Repository Citation: Pace, I. (2012). Instrumental performance in the nineteenth century. In: Lawson, C. and Stowell, R. (Eds.), The Cambridge History of Musical Performance. (pp. 643-695). Cambridge University Press. This is the accepted version of the paper. This version of the publication may differ from the final published version. Permanent repository link: https://openaccess.city.ac.uk/id/eprint/6305/ Link to published version: http://dx.doi.org/10.1017/CHOL9780521896115.027 Copyright: City Research Online aims to make research outputs of City, University of London available to a wider audience. Copyright and Moral Rights remain with the author(s) and/or copyright holders. URLs from City Research Online may be freely distributed and linked to. Reuse: Copies of full items can be used for personal research or study, educational, or not-for-profit purposes without prior permission or charge. Provided that the authors, title and full bibliographic details are credited, a hyperlink and/or URL is given for the original metadata page and the content is not changed in any way. City Research Online: http://openaccess.city.ac.uk/ [email protected] C:/ITOOLS/WMS/CUP-NEW/2654833/WORKINGFOLDER/LASL/9780521896115C26.3D 643 [643–695] 5.9.2011 7:13PM . 26 . Instrumental performance in the nineteenth century IAN PACE 1815–1848 Beethoven, Schubert and musical performance in Vienna from the Congress until 1830 As a major centre with a long tradition of performance, Vienna richly reflects