Chapter Two Humans and Space: Stories, Images, Music and Dance Jim Dator

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

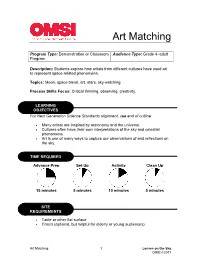

Art Matching

Art Matching Program Type: Demonstration or Classroom Audience Type: Grade 4–adult Program Description: Students explore how artists from different cultures have used art to represent space-related phenomena. Topics: Moon, space travel, art, stars, sky-watching Process Skills Focus: Critical thinking, observing, creativity. LEARNING OBJECTIVES For Next Generation Science Standards alignment, see end of outline. • Many artists are inspired by astronomy and the universe. • Cultures often have their own interpretations of the sky and celestial phenomena. • Art is one of many ways to capture our observations of and reflections on the sky. TIME REQUIRED Advance Prep Set Up Activity Clean Up 15 minutes 5 minutes 10 minutes 5 minutes SITE REQUIREMENTS • Table or other flat surface • Chairs (optional, but helpful for elderly or young audiences) Art Matching 1 Lenses on the Sky OMSI 2017 PROGRAM FORMAT Segment Format Time Introduction Large group discussion 2 min Art Matching Group Activity 5 min Wrap-Up Large group discussion 3 min SUPPLIES Permanent Supplies Amount Notes Laminated pages showing the artists 5 and their work Laminated cards showing 5 astronomical images ADVANCE PREPARATION • Print out, cut, and laminate the pages showing the artists and their work (at the end of the document). • Print out, cut, and laminate the five cards showing the astronomical images (at the end of the document). • Complete the activity to familiarize yourself with the process. SET UP Spread out the five pages showing the artists and their work on the table. Below the pages, place the five cards showing the astronomical objects. INTRODUCTION 2 minutes Let students speculate before offering answers to any questions. -

Note to Users

NOTE TO USERS Page(s) not included in the original manuscript are unavailable from the author or university. The manuscript was microfilmed as received 88-91 This reproduction is the best copy available. UMI INFORMATION TO USERS The most advanced technology has been used to photo graph and reproduce this manuscript from the microfilm master. UMI films the original text directly from the copy submitted. Thus, some dissertation copies are in typewriter face, while others may be from a computer printer. In the unlikely event that the author did not send UMI a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if unauthorized copyrighted material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. Oversize materials (e.g., maps, drawings, charts) are re produced by sectioning the original, beginning at the upper left-hand comer and continuing from left to right in equal sections with small overlaps. Each oversize page is available as one exposure on a standard 35 mm slide or as a 17" x 23" black and white photographic print for an additional charge. Photographs included in the original manuscript have been reproduced xerographically in this copy. 35 mm slides or 6" X 9" black and white photographic prints are available for any photographs or illustrations appearing in this copy for an additional charge. Contact UMI directly to order. AccessinglUMI the World’s Information since 1938 300 North Zeeb Road, Ann Arbor, Mi 48106-1346 USA Order Number 8820263 Leigh Brackett: American science fiction writer—her life and work Carr, John Leonard, Ph.D. -

Programme Book COLOPHON

tolkien society UNQUENDOR lustrum day saturday 19 june 2021 celebrating unquendor's 40th anniversary theme: númenor 1 programme book COLOPHON This programme book is offered to you by the Lustrum committee 2021. Bram Lagendijk and Jan Groen editors Bram Lagendijk design and lay out For the benefit of the many international participants, this programme book is in English. However, of the activities, only the lectures are all in English. The other activities will be in Dutch, occasionally interspersed with English. tolkien society unquendor E-mail: [email protected] Internet: www.unquendor.nl Instagram: www.instagram.com/unquendor Facebook: www.facebook.com/groups/unquendor Twitter: www.twitter.com/unquendor Youtube: www.youtube.com/user/tolkiengenootschap Discord: www.discord.gg/u3wwqHt9RE June 2021 CONTENTS Getting started ... 4 A short history of Unquendor 5 Things you need to know 6 Númenor: The very short story 7 Programme and timetable 8 y Lectures 9 Denis Bridoux Tall ships and tall kings Númenor: From Literary Conception y to Geographical Representation 9 Renée Vink Three times three, The Uncharted Consequences of y the Downfall of Númenor 9 What brought they from Hedwig SlembrouckThe Lord of the Rings Has the history of the Fall of Númenor y been told in ?? 9 the foundered land José Maria Miranda y Law in Númenor 9 Paul Corfield Godfrey, Simon Crosby Buttle Over the flowing sea? WorkshopsThe Second Age: A Beginning and an End 910 y Seven stars and seven stones Nathalie Kuijpers y Drabbles 10 QuizJonne Steen Redeker 10 And one white tree. Caroline en Irene van Houten y Jan Groen Gandalf – The Two Towers y Poem in many languages 10 Languages of Númenor 10 Peter Crijns, Harm Schelhaas, Dirk Trappers y Dirk Flikweert IntroducingLive cooking: the presentersNúmenórean fish pie 1011 Festive toast and … 14 Participants 15 Númenórean fish pie 16 Númenóreaanse vispastei 17 GETTING STARTED… p deze Lustrumdag vieren we het 40-jarig Obestaan van Unquendor! Natuurlijk, we had- den een groot Lustrumfeest voor ogen, ons achtste. -

BRINGING the WAR HOME the PATRIOTIC IMAGINATION in SASKATOON, 1939-1942 Brendan Kelly University of Toronto

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by UNL | Libraries University of Nebraska - Lincoln DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln Great Plains Quarterly Great Plains Studies, Center for Spring 2010 BRINGING THE WAR HOME THE PATRIOTIC IMAGINATION IN SASKATOON, 1939-1942 Brendan Kelly University of Toronto Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.unl.edu/greatplainsquarterly Part of the American Studies Commons, Cultural History Commons, and the United States History Commons Kelly, Brendan, "BRINGING THE WAR HOME THE PATRIOTIC IMAGINATION IN SASKATOON, 1939-1942" (2010). Great Plains Quarterly. 2574. http://digitalcommons.unl.edu/greatplainsquarterly/2574 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Great Plains Studies, Center for at DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. It has been accepted for inclusion in Great Plains Quarterly by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. BRINGING THE WAR HOME THE PATRIOTIC IMAGINATION IN SASKATOON, 1939-1942 BRENDAN KELLY I n The American West Transformed: The histories of urban centers in wartime: Red Impact of the Second World War, noted histo Deer (Alberta), Lethbridge (Alberta), and rian Gerald D. Nash argued that the war, more Regina (Saskatchewan).3 However, these than any other event in the West's history, previous studies pay insufficient attention to completely altered that region.1 There is as the impact of "patriotism," a curious omission yet no equivalent of Nash's fine study for the given how frequently both government officials Great Plains north of the forty-ninth parallel, and ordinary citizens used their love of coun or what Canadians call the "prairies."2 This try as a rallying cry. -

A European Cooperation Programme

Year 32 • Issue #363 • July/August 2019 2,10 € ESPAÑOLA DE InternationalFirst Edition Defence of the REVISTA DEFEandNS SecurityFEINDEF ExhibitionA Future air combat system A EUROPEAN COOPERATION PROGRAMME BALTOPS 2019 Spain takes part with three vessels and a landing force in NATO’s biggest annual manoeuvres in the Baltic Sea ESPAÑOLA REVISTA DE DEFENSA We talk about defense NOW ALSO IN ENGLISH MANCHETA-INGLÉS-353 16/7/19 08:33 Página 1 CONTENTS Managing Editor: Yolanda Rodríguez Vidales. Editor in Chief: Víctor Hernández Martínez. Heads of section. Internacional: Rosa Ruiz Fernández. Director de Arte: Rafael Navarro. Parlamento y Opinión: Santiago Fernández del Vado. Cultura: Esther P. Martínez. Fotografía: Pepe Díaz. Sections. Nacional: Elena Tarilonte. Fuerzas Armadas: José Luis Expósito Montero. Fotografía y Archivo: Hélène Gicquel Pasquier. Maque- tación: Eduardo Fernández Salvador. Collaborators: Juan Pons. Fotografías: Air- bus, Armada, Dassault Aviation, Joaquín Garat, Iñaki Gómez, Latvian Army, Latvian Ministry of Defence, NASA, Ricardo Pérez, INDUSTRY AND TECHNOLOGY Jesús de los Reyes y US Navy. Translators: Grainne Mary Gahan, Manuel Gómez Pumares, María Sarandeses Fernández-Santa Eulalia y NGWS, Fuensanta Zaballa Gómez. a European cooperation project Germany, France and Spain join together to build the future 6 fighter aircraft. Published by: Ministerio de Defensa. Editing: C/ San Nicolás, 11. 28013 MADRID. Phone Numbers: 91 516 04 31/19 (dirección), 91 516 04 17/91 516 04 21 (redacción). Fax: 91 516 04 18. Correo electrónico:[email protected] def.es. Website: www.defensa.gob.es. Admi- ARMED FORCES nistration, distribution and subscriptions: Subdirección General de Publicaciones y 16 High-readiness Patrimonio Cultural: C/ Camino de Ingenieros, 6. -

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 268 480 CS 008 354 TITLE All Aboard The

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 268 480 CS 008 354 TITLE All Aboard the Reading Railroad! A Planning and Activity Guide. INSTITUTION Nebraska Library Association, Lincoln.; Nebraska Library Commission, Linctin. PUB DATE 85 NOTE 157p. AVAILABLE FROMNebraska Library Commission, 1420 P. St., Lincoln, NE 68508 ($3.00). PUB TYPE Guides Non-Classroom Use (055) EDRS PRICE MF01/PC07 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS Activities; Bibliographies; Elementary Education; Folk Culture; Library Extension; *Motivation Techniques; *Rail Transportation; Reading Habits; Reading Improvement; *Reading Programs; *Summer Programs; Thematic Approach ABSTRACT Noting that coupling stories and trains is an arrangement that appeals to nearly everyone and that building on this foundation provides an excellent theme fot summer reading ftul, this planning and activity guide offers suggestions to help librarians develop a highly motivating summer reading program. The first section of the guide discusses establishing an effective publicity campaign. The remaining sections of the guide present resources and activities for the program es follows: (1) bibliographies of materials about trains; (2) sources and resources for railroad information and collectibles; (3) railroad stories to tell (including "mad libs," flannel board stories, and railroad songs); (4) puppets and puppet theatre; (5) bulletin boards and displays; (6) crafts and activities; (7) games and contests; (8) puzzles; and (9) special programs and culminating activities. (HTH) *********************************************************************** Reproductions supplied by EDRS are the best that can be made from the original document. *********************************************************************?* U 8 DEPARTMENT OF EDUCATION Office of Educational Research and improvement EDUCATIONAL RESOURCES INFORMATION CENTER iERICI Tn is document has been reproduced as ecevrti from the person or organtzation .r,Qpnrthr,c4t Yr,t,,, t ha0ges have been made to Improve ,opt du, t'JrQuaid, ,II,,,ev. -

Mcdowell Title Page

UC Berkeley UC Berkeley Electronic Theses and Dissertations Title House Work: Domesticity, Belonging, and Salvage in the Art of Jess, 1955-1991 Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/5mf693nb Author McDowell, Tara Publication Date 2013 Peer reviewed|Thesis/dissertation eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California House Work: Domesticity, Belonging, and Salvage in the Art of Jess, 1955-1991 By Tara Cooke McDowell A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in History of Art in the Graduate Division of the University of California, Berkeley Committee in charge: Professor Emerita Anne M. Wagner, Chair Professor Emeritus T.J. Clark Professor Emerita Kaja Silverman Spring 2013 Abstract House Work: Domesticity, Belonging, and Salvage in the Art of Jess, 1955-1991 by Tara McDowell Doctor of Philosophy in History of Art University of California, Berkeley Professor Emerita Anne M. Wagner, Chair This dissertation examines the work of the San Francisco-based artist Jess (1923-2004). Jess’s multimedia and cross-disciplinary practice, which takes the form of collage, assemblage, drawing, painting, film, illustration, and poetry, offers a perspective from which to consider a matrix of issues integral to the American postwar period. These include domestic space and labor; alternative family structures; myth, rationalism, and excess; and the salvage and use of images in the atomic age. The dissertation has a second protagonist, Robert Duncan (1919-1988), preeminent American poet and Jess’s partner and primary interlocutor for nearly forty years. Duncan and Jess built a household and a world together that transgressed boundaries between poetry and painting, past and present, and acknowledged the limits and possibilities of living and making daily. -

Far-Infrared Observations of a Massive Cluster Forming in the Monoceros R2 filament Hub? T

Astronomy & Astrophysics manuscript no. monr2_hobys˙final˙corrected c ESO 2017 December 5, 2017 Far-infrared observations of a massive cluster forming in the Monoceros R2 filament hub? T. S. M. Rayner1??, M. J. Griffin1, N. Schneider2; 3, F. Motte4; 5, V. K¨onyves5, P. Andr´e5, J. Di Francesco6, P. Didelon5, K. Pattle7, D. Ward-Thompson7, L. D. Anderson8, M. Benedettini9, J.-P. Bernard10, S. Bontemps3, D. Elia9, A. Fuente11, M. Hennemann5, T. Hill5; 12, J. Kirk7, K. Marsh1, A. Men'shchikov5, Q. Nguyen Luong13; 14, N. Peretto1, S. Pezzuto9, A. Rivera-Ingraham15, A. Roy5, K. Rygl16, A.´ S´anchez-Monge2, L. Spinoglio9, J. Tig´e17, S. P. Trevi~no-Morales18, and G. J. White19; 20 1 Cardiff School of Physics and Astronomy, Cardiff University, Queen's Buildings, The Parade, Cardiff, Wales, CF24 3AA, UK 2 I. Physik. Institut, University of Cologne, 50937 Cologne, Germany 3 Laboratoire d'Astrophysique de Bordeaux, Univ. Bordeaux, CNRS, B18N, all´eeG. Saint-Hilaire, 33615 Pessac, France 4 Universit´eGrenoble Alpes, CNRS, Institut de Planetologie et d'Astrophysique de Grenoble, 38000 Grenoble, France 5 Laboratoire AIM, CEA/IRFU { CNRS/INSU { Universit´eParis Diderot, CEA-Saclay, 91191 Gif-sur-Yvette Cedex, France 6 NRC, Herzberg Institute of Astrophysics, Victoria, Canada 7 Jeremiah Horrocks Institute, University of Central Lancashire, Preston PR1 2HE, UK 8 Department of Physics and Astronomy, West Virginia University, Morgantown, WV 26506, USA 9 INAF { Istituto di Astrofisica e Planetologia Spaziali, via Fosso del Cavaliere 100, I-00133 Roma, Italy 10 -

Original Space Art Purpose

Original Space Art Purpose of Illustrate the precision and beauty of two of America’s premiere space artists. Scope Paul & Chris Calle All material are original sketches and paintings created by Paul and Chris Calle. When a choice of cachets was available, artwork that most closely replicated the postage stamp was chosen. Plan Project Mercury 1959-1963 Project Gemini 1962-1966 Project Apollo 1961-1975 “They really wanted to send a dog, but they decided that would be too cruel.” Alan Shepard In 1962 NASA Administrator Jim Webb invited artists to record the strange new world of space. Of the original cadre, Paul Calle, an illustrator of science fiction book covers, joined Robert McCall and six others and began to sketch. As commissioned artists they received $800 and access to draw a blossoming manned space program. Over the years the NASA Art Program would include the works of pop artist Andy Warhol, photographer Annie Leibovitz, and American illustrator Norman Rockwell. Paul Calle remained associated with NASA from Mercury through Gemini, Apollo, and the Space Shuttle. Over the years, he helped guide his son Chris to become a serious artist in his own right. Paul would design over 50 stamps for the Post Office Department and the US Postal Service including the Gemini space twins in 1967 and the First Man on the Moon issue of 1969. To beat the Soviets in putting a man in space, the US Air Force selected nine pilots Chris collaborated with his father on two space stamps to celebrate the 25th for Man In Space Soonest (MISS). -

Data Delivery Document

The CygnusX Legacy Project Data Description: Delivery 1: July 2011 CygnusX team: Joseph L. Hora1 (PI), Sylvain Bontemps2, Tom Megeath3, Nicola Schneider4 , Frederique Motte4, Sean Carey5, Robert Simon6, Eric Keto1, Howard Smith1, Lori Allen7, Rob Gutermuth8, Giovanni Fazio1, Kathleen Kraemer9, Don Mizuno10, Stephan Price9, Joseph Adams11, Xavier Koenig12 1Harvard-Smithsonian Center for Astrophysics, 2Observatoire de Bordeaux, 3University of Toledo, 4CEA-Saclay, 5Spitzer Science Center, 6Universität zu Köln, 7NOAO, 8Smith College, 9Air Force Research Lab, 10Boston College, 11Cornell University, 12Goddard Space Flight Center Table of Contents 1. Project Summary ..................................................................................................................... 3 1.1 IRAC observations ........................................................................................................... 3 1.2 MIPS observations ........................................................................................................... 4 1.3 Data reduction .................................................................................................................. 5 1.3.1 IRAC reduction ......................................................................................................... 5 1.3.2 MIPS reduction ......................................................................................................... 7 2. Point Source Catalog.............................................................................................................. -

Through Astronaut Eyes: Photographing Early Human Spaceflight

Purdue University Purdue e-Pubs Purdue University Press Book Previews Purdue University Press 6-2020 Through Astronaut Eyes: Photographing Early Human Spaceflight Jennifer K. Levasseur Follow this and additional works at: https://docs.lib.purdue.edu/purduepress_previews This document has been made available through Purdue e-Pubs, a service of the Purdue University Libraries. Please contact [email protected] for additional information. THROUGH ASTRONAUT EYES PURDUE STUDIES IN AERONAUTICS AND ASTRONAUTICS James R. Hansen, Series Editor Purdue Studies in Aeronautics and Astronautics builds on Purdue’s leadership in aeronautic and astronautic engineering, as well as the historic accomplishments of many of its luminary alums. Works in the series will explore cutting-edge topics in aeronautics and astronautics enterprises, tell unique stories from the history of flight and space travel, and contemplate the future of human space exploration and colonization. RECENT BOOKS IN THE SERIES British Imperial Air Power: The Royal Air Forces and the Defense of Australia and New Zealand Between the World Wars by Alex M Spencer A Reluctant Icon: Letters to Neil Armstrong by James R. Hansen John Houbolt: The Unsung Hero of the Apollo Moon Landings by William F. Causey Dear Neil Armstrong: Letters to the First Man from All Mankind by James R. Hansen Piercing the Horizon: The Story of Visionary NASA Chief Tom Paine by Sunny Tsiao Calculated Risk: The Supersonic Life and Times of Gus Grissom by George Leopold Spacewalker: My Journey in Space and Faith as NASA’s Record-Setting Frequent Flyer by Jerry L. Ross THROUGH ASTRONAUT EYES Photographing Early Human Spaceflight Jennifer K. -

Celebrating the Wonder of the Night Sky

Celebrating the Wonder of the Night Sky The heavens proclaim the glory of God. The skies display his craftsmanship. Psalm 19:1 NLT Celebrating the Wonder of the Night Sky Light Year Calculation: Simple! [Speed] 300 000 km/s [Time] x 60 s x 60 m x 24 h x 365.25 d [Distance] ≈ 10 000 000 000 000 km ≈ 63 000 AU Celebrating the Wonder of the Night Sky Milkyway Galaxy Hyades Star Cluster = 151 ly Barnard 68 Nebula = 400 ly Pleiades Star Cluster = 444 ly Coalsack Nebula = 600 ly Betelgeuse Star = 643 ly Helix Nebula = 700 ly Helix Nebula = 700 ly Witch Head Nebula = 900 ly Spirograph Nebula = 1 100 ly Orion Nebula = 1 344 ly Dumbbell Nebula = 1 360 ly Dumbbell Nebula = 1 360 ly Flame Nebula = 1 400 ly Flame Nebula = 1 400 ly Veil Nebula = 1 470 ly Horsehead Nebula = 1 500 ly Horsehead Nebula = 1 500 ly Sh2-106 Nebula = 2 000 ly Twin Jet Nebula = 2 100 ly Ring Nebula = 2 300 ly Ring Nebula = 2 300 ly NGC 2264 Nebula = 2 700 ly Cone Nebula = 2 700 ly Eskimo Nebula = 2 870 ly Sh2-71 Nebula = 3 200 ly Cat’s Eye Nebula = 3 300 ly Cat’s Eye Nebula = 3 300 ly IRAS 23166+1655 Nebula = 3 400 ly IRAS 23166+1655 Nebula = 3 400 ly Butterfly Nebula = 3 800 ly Lagoon Nebula = 4 100 ly Rotten Egg Nebula = 4 200 ly Trifid Nebula = 5 200 ly Monkey Head Nebula = 5 200 ly Lobster Nebula = 5 500 ly Pismis 24 Star Cluster = 5 500 ly Omega Nebula = 6 000 ly Crab Nebula = 6 500 ly RS Puppis Variable Star = 6 500 ly Eagle Nebula = 7 000 ly Eagle Nebula ‘Pillars of Creation’ = 7 000 ly SN1006 Supernova = 7 200 ly Red Spider Nebula = 8 000 ly Engraved Hourglass Nebula