Children: Producing a Hierarchy of Learners in Primary School Processes

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Mick Geyer in 1996: NC: Mr Mick Geyer, My Chief Researcher and Guru, He Is the Man Behind the Scenes

www.pbsfm.org.au FULL TRANSCRIPT OF DOCUMENTARY #3 First broadcast on PBS-FM Wednesday 12 April 2006, 7-8pm Nick Cave interviewing Mick Geyer in 1996: NC: Mr Mick Geyer, my chief researcher and guru, he is the man behind the scenes. How important is music to you? MG: It seems to be a fundamental spirit of existence in some kind of way. The messages of musicians seem to be as relevant as those of any other form of artistic expression. MUSIC: John Coltrane - Welcome (Kulu Se Mama) LISA PALERMO (presenter): Welcome to 'Mick Geyer: Music Guru'. I'm Lisa Palermo and this is the third of four documentaries paying tribute to Mick, a broadcaster and journalist in the Melbourne music scene in the 1980's and '90's. Mick died in April 2004 of cancer of the spine. He had just turned 51. His interests and activities were centred on his love of music, and as you'll hear from recent interviews and archival material, his influence was widespread, but remained largely outside the public view. In previous programs we heard about the beginnings of his passion for music, and his role at PBS FM, behind the scenes and on the radio. Now we'll explore Mick as a catalyst and friend to many musicians, through conversation and the legendary Geyer tapes, those finely crafted compilations of musical enlightenment and education. In this program we'll hear for the first time from: musicians Dave Graney & Clare Moore, Jex Saarelaht, Hugo Race, Tex Perkins, Warren Ellis, Kim Salmon, Brian Hooper, Charlie Owen, and Penny Ikinger; and from friends Beau Cummin, Mariella del Conte, Stephen Walker and Warwick Brown. -

Australian Rules Music Credits

Original Music Mick Harvey Original Music Composed, Performed and Produced by Mick Harvey Original Music Published by Birthday Party Pty Limited Recorded and Mixed at The Vault, Sydney Engineered by James Cadsky “Darcy’s Theme” Written by Matt Walker Courtesy of Sony/ATV Music Publishing Recorded at Cloud Nine by Phil Downing “Pickles’ Theme” Written by Matt Walker and Ashley Davies Courtesy of Sony/ATV Music Publishing Additional Musicians Lap Steel Guitar Matt Walker Violin Naomi Radom Violin Airena Nakamura Cello Chloe Miller Drums Ashley Davies “What I Done to Her” (Perkins/Owen), Performed by Tex, Don and Charlie Licensed by PolyGram Music Publishing Pty Limited Administered by Universal Music Australia Pty Limited Courtesy of Polydor Records, Licensed from Universal Music Australia Pty Limited “My Mind’s Sedate” (Kippenberger/Knight/Toogood/Larkin), Performed by Shihad Licensed by PolyGram Music Publishing Pty Limited Administered by Universal Music Australia Pty Limited Licensed courtesy of Warner Music Australia Pty Limited “Wishbone” (Rivers/Rohde/Moffatt), Performed by Red Rivers Licensed by Rondor Music Australia Pty Limited Administered by Universal Music Australia Pty Limited Courtesy Compass Brothers/ Festival Mushroom Records Australia Pty Limited “Skippy Theme” Performed by Tom Budge, Courtesy of Eric Stanley Jupp CD: A CD of the soundtrack was released: CD Mute IONIC17CD 2003 Guest Musicians: Matt Waiker - Lap Steel Guitar Ashley Davies - Drums (3 & 10) Naomi Radom – Violin Airena Nakamura – Violin Chloe Miller – Cello -

Adelaide FESTIVAL of ARTS 2016

adelaide FESTIVAL OF ARTS 2016 26 feb - 14 mar WELCOME David Sefton Jay Weatherill Jack Snelling ARTISTIC DIRECTOR PREMIER OF SOUTH AUSTRALIA MINISTER FOR THE ARTS It is with a bundle of mixed emotions that I welcome you I'm also delighted in my final festival to be able to The 2016 Adelaide Festival of Arts promises to be 18 Our Adelaide Festival of Arts has a fantastic reputation for to the 2016 Adelaide Festival of Arts, my final selection showcase so much great work from South Australia. unforgettable days of boldness and exuberance. bringing new and exclusive art to our city, and this year’s as Artistic Director. One of the joys of my time here has been the discovery program is no exception. It will start with a breathtaking show on our biggest stage, of just how much world-class work is made locally and The last three years have been an amazing journey and with Groupe F’s opening-night pyrotechnic spectacular À A major coup for this year will be the presentation of it is a particular pleasure to include a powerful cross- 2016 promises to be just as fabulous. For this final festival Fleur de Peau illuminating the magnificent Adelaide Oval. The James Plays – a trilogy of plays about the three kings section of it this year. I am delighted that we'll see the epic and the intimate, of Scotland. An Australian premiere exclusive to Adelaide, Another feature of the festival is Adelaide Writers’ Week – six the traditional and the new and the range of excellence I'm enormously proud of all of the festivals I have Rona Munro’s new historical trilogy is the type of days of readings and discussions about books and ideas in people have come to expect from this festival. -

DT-Fullthesis Amendedfinalversion 1102017

Learning to innovate collaboratively with technology: Exploring strategic workplace skill webs in a telecom services firm in Tehran Náder Alyani A Thesis Submitted for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy (Social Science) LLAKES Centre Institute of Education University College London October 2017 1 Abstract This thesis explores innovation and learning within the context of an entrepreneurial new technology based firm (NTBF), operating in the creative sector of telecommunications value- added services located in Tehran, Iran, along with a partner in London, UK. Whilst backgrounding the socioeconomic and geopolitical characteristics of the operating environment, and historical antecedents of independence and self-sufficiency, plus chronic sanctions within the economy, the argument focuses on the interplay between intermediated learning via strategic ‘skill webs’ leading to innovation. Drawing on innovation and workplace learning corpus, collaborative innovation with technologies is organised as a competitive action in an unstable and unpredictable market: learning and skill enhancement in firms provides the stabilisers to remain and compete in the market. It is the juxtaposition of learning and innovation in service-innovation/-delivery design, while utilising pervasive and emerging telecoms technologies that provides the empirical base for this research. Conceptually, an emergent type of distributed learning, entitled as ‘DEAL’ (Design, Execute, Adjust and Learn) model, by enabling knowledge brokerage facilitated by ‘skill webs’, is identified and explored. This then acts as an analytical tool to examine the empirical elements which are in the form of longitudinal organisational ethnography on site visit waves, spanning 2004 to 2013, focusing on project learning breakthroughs and cul-de-sacs as observed by learning episodes, often utilising informal networks and skill webs in technical and non-technical tasks. -

Life in a Padded Cell: a Biography of Tony Cohen, Australian Sound Engineer by Dale Blair ©Copyright

Life in a Padded Cell: A Biography of Tony Cohen, Australian Sound Engineer by Dale Blair ©copyright ~ One ~ Satan has possessed your Soul! ‘Tony is very devout in “God’s Lesson”. I cannot speak highly enough of Tony’s manners and behaviour. They are beyond reproach’. It was the sort of report card every parent liked to see. It was 1964. The Beatles were big and Tony Cohen was a Grade One student at St. Francis de Sales primary school, East Ringwood. The following year he took his first communion. The Beatles were still big and there seemed little to fear for the parents of this conscientious and attentive eight-year-old boy. The sisters who taught him at that early age would doubtless have been shocked at the life he would come to lead – a life that could hardly be described as devout. Tony Cohen was born on 4 June 1957 in the maternity ward of the Jessie MacPherson hospital in Melbourne. Now a place specializing in the treatment of cancer patients it was a general hospital then. He was christened Anthony Lawrence Cohen. His parents Philip and Margaret Cohen had been living in James Street, Windsor, but had moved to the outer eastern suburb of East Ringwood prior to the birth of their son. Philip Cohen was the son of Jewish immigrants who had left Manchester, England, and settled in Prahran, one of Melbourne’s inner eastern suburbs. Philip’s father had served in the First World War, survived and then migrated to Australia with his wife and infant son (Tony’s Uncle David). -

Download Media

Artist Biography: Penny Ikinger Penny Ikinger is an antipodean rock maestro who defies easy comparison and definition. With her iconic guitar, the Pennycaster, she is a fuzz queen, sonic chanteuse and primal mistress of dark folk who wows her audiences at home in Australia and beyond Penny’s impressive career started as guitarist in Wet Taxis with Louis Tillett, going on to perform and record with many acclaimed artists such as Deniz Tek (Radio Birdman), Kim Salmon, Tex Perkins and the Sacred Cowboys. In 2003 Penny launched out on her own and her undeniable solo talents began to be noticed. Penny’s debut album Electra (Career Records, USA/ Bang! Records, Spain) was filled with breathy vocals and sonic guitar exploring the aural landscape where sonic disfigurement entwines with femme fatale pop.Electra appeared in Top Ten lists (at #2 by critics from prestigious New York magazines The Village Voice and The Big Takeover) and numerous music publications in the USA, Europe, Canada and Australia. “All woman and all business - the Australian singer-guitarist - a graduate of the Radio Birdman school of axe warfare - unveils a fetching line of balladry here: black-hearted folk song draped in fuzz, topped with a dark baby-doll whisper...imagine Nico channelling Sandy Denny in front of blue Oyster Cult - and you’re close.” David Fricke, Rolling Stone (USA) The release of Penny’s second album Penelope (Citadel Records, Australia), signaled her evolving sound with a style and tempo shift. This album, full of stories of life, love and redemption, is also a collection of three-minute classic pop gems that mix post-punk attack with swingin’ 60’s attitude and 70’s guitar experimentation. -

Exhibition Catalogue

www.sl.nsw.gov.au WHAT A LIFE! ROCK PHOTOGRAPHY BY TONY MOTT :: 1 State Library of NSW Printer: Peachy Print Curator: Louise Tegart Thanks to Tony Mott, Toby Creswell Macquarie Street Clinton Walker, Tim Rogers, Paper: KW Doggetts Maine Recycled Creative Producer: Karen Hall Sydney NSW 2000 Missy Higgins, Jenny and Gloss 130 gsm 60% recycled and Telephone (02) 9273 1414 Exhibition Designers: Margaret Cott, Kasey Chambers Envirocare 70 gsm 100% recycled www.sl.nsw.gov.au Jemima Woo and Karen Wong and Paul Mac Print run: 12,000 A free exhibition Graphic Designer: Simon Leong Above: Tony Mott 2014 at the State Library of NSW P&D-4535-10/2015 © Graham Jepson from 17 October 2015 Editor: Cathy Perkins All images unless otherwise noted to 7 February 2016 ISBN 0 7313 7228 X Illustrator: Ben Brown (front cover) are courtesy and © Tony Mott © State Library of New South Wales Exhibition opening hours: Creative Producer, Multimedia: October 2015 Weekdays 9 am to 5 pm Sabrina Organo Thursdays until 8 pm Back cover: Chrissy Amphlett, Divinyls 1983 Weekends 10 am to 5 pm Senior Conservator, This is the first photo I ever sold. Without Exhibitions & Loans: Helen Casey Chrissy, I wouldn’t have a career. I sort of stalked her with my camera to learn the art Follow us on Registrar: Caroline Lorentz of rock photography. What a pleasure and #RockMoments @statelibrarynsw pain it was. — TM 2 :: WHAT A LIFE! ROCK PHOTOGRAPHY BY TONY MOTT www.sl.nsw.gov.au www.sl.nsw.gov.au WHAT A LIFE! ROCK PHOTOGRAPHY BY TONY MOTT :: 3 Björk 1994 One of my most published images, this What a Life! photo of Björk was taken at the Big Day Out in 1994. -

Penelope Inc PARIS

penelope inc PARIS... TOKYO and beyond Past, present, future... Penny Ikinger has a rich musical history - she is a woman with a past, some might say. She is also a woman with a future... This year Penny Ikinger will complete her second full length album - a vibrant mix of pop, garage music with a delectable splash of groove. Penny will be touring Europe and Tokyo September/October 2008, playing songs from her new album due for release 2009. Joining her in Europe will be Parisienne musicians Dimi Dero (drums) and Vinz Guilluy (bass). The three piece toured Europe in 2006 and Australia 2007 and they are back in September 2008 as: penelope inc. Dimi Dero and Vinz Guilluy appear on Penny’s second album along with Deniz Tek, Charlie Owen, Dave Graney & Clare Moore et al... For her gigs in Tokyo she will be performing solo. “All woman and all business – the Australian singer-guitarist, a graduate of the Radio Birdman school of axe warfare – unveils a fetching line of balladry here: black-hearted folk song draped in fuzz, topped with a dark baby-doll whisper...imagine Nico channelling Sandy Denny in front of blue Oyster Cult - and you’re close.” David Fricke, Senior Editor, Rolling Stone (USA) Penny will also be touring Australia and beyond in 2008-09 to promote her new album and has been hand picked for an upcoming tour with US guitar legend Adrian Belew, who she supported in Australia in 2006. “Toe-nail polish and noise guitar. Sexy silvery sandals and breathy, twisitng and turning vocals. -

Q1 2020 Q1 2020 Lewis Lewis Capaldi Mabel Dav E Celeste Billie Eilish

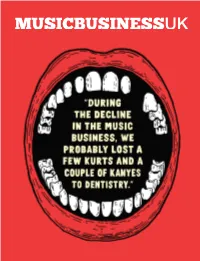

Q1 2020 Q1 2020 CONGRATULATIONS ON YOUR BRIT YOUR ON CONGRATULATIONS FROM EVERYONE AT UNIVERSAL MUSIC UNIVERSAL AT EVERYONE FROM s SUCCESS LEWIS LEWIS CAPALDI MABEL DAV E CELESTE BILLIE EILISH 11 WELCOME EDITOR’S LETTER In this issue... The popular modern maxim to ‘speak my truth’ Tim Ingham long it will take, or how much ownership they tacitly yet proudly argues there is always more are giving up. Then, they compete for attention 10 YouTube Music than one retelling of any event – bending every and resources that are already spread thin. It’s a Dan Chalmers & Lyor Cohen occurrence into a fiction-splashed narrative fight for creative and financial freedom.” onto which our own subjective viewpoint can, This attack on traditional label advances is the and should, be impressed. It adds to a collective latest broadside to be thrown on a voluminous 22 Kyn Entertainment erosion of the idea of the gospel – whether pile. Elsewhere, rapper Mase recently castigated Sonny Takhar religious, journalistic or anecdotal – furthering Puff Daddy on Instagram regarding a historical a rabid culture of self-trust. It is malleable, and publishing deal between the pair. Mase said that therefore open to manipulation, ego and error. Puff “purposely starved your artist”, adding: “For 28 The BRIT Awards It is the definition of Trump’s America. example, u still got my publishing from 24 years How did we end up in this situation, where ago in which u gave me $20k.” one person’s reality – no matter how warped by What is lost in both Rabkin Lewis and Mase’s self-serving myopia – has become more valued salvos here is a rounded view – the rapidly- 38 Nick Burgess & Mark Mitchell Parlophone than art, and more trusted than evidence? vanishing gift of being taught all sides of the I mean, it can’t all be down to TikTok. -

Rock Photography by Tony Mott

www.sl.nsw.gov.au WHAT A LIFE! ROCK PHOTOGRAPHY BY TONY MOTT :: 1 State Library of NSW Printer: Spotpress Curator: Louise Tegart Thanks to Tony Mott, Toby Creswell Macquarie Street Clinton Walker, Tim Rogers, Paper: Sappi 80 gsm gloss (cover), Creative Producer: Karen Hall Sydney NSW 2000 Missy Higgins, Jenny and UPM 70 gsm bond (text) Telephone (02) 9273 1414 Exhibition Designers: Margaret Cott, Kasey Chambers www.sl.nsw.gov.au Print run: 8000 Jemima Woo and Karen Wong and Paul Mac P&D-4535-4/2016 Graphic Designer: Simon Leong Above: Tony Mott 2014 Follow us on © Graham Jepson #RockMoments @statelibrarynsw ISBN 0 7313 7231 X Editor: Cathy Perkins All images unless otherwise noted Reprinted for the tour of What a Life! © State Library of New South Wales Illustrator: Ben Brown (front cover) are courtesy and © Tony Mott October 2015 Rock Photography by Tony Mott Creative Producer, Multimedia: Sabrina Organo Some images in this publication are Back cover: Chrissy Amphlett, Divinyls 1983 not included in the touring exhibition. Senior Conservator, This is the first photo I ever sold. Without Exhibitions & Loans: Helen Casey Chrissy, I wouldn’t have a career. I sort of stalked her with my camera to learn the art Registrar: Caroline Lorentz of rock photography. What a pleasure and pain it was. — TM 2 :: WHAT A LIFE! ROCK PHOTOGRAPHY BY TONY MOTT www.sl.nsw.gov.au www.sl.nsw.gov.au WHAT A LIFE! ROCK PHOTOGRAPHY BY TONY MOTT :: 3 What a Life! Rock Photography by Tony Mott his exhibition showcases rock’n’roll life — on stage Tand behind the scenes — captured by Australia’s premier rock photographer Tony Mott over a 30-year career. -

The New Christs Distemper Mp3, Flac, Wma

The New Christs Distemper mp3, flac, wma DOWNLOAD LINKS (Clickable) Genre: Rock Album: Distemper Country: Greece Released: 1989 Style: Alternative Rock, Garage Rock MP3 version RAR size: 1442 mb FLAC version RAR size: 1808 mb WMA version RAR size: 1690 mb Rating: 4.5 Votes: 980 Other Formats: MIDI MP1 RA AU AUD MP2 DXD Tracklist Hide Credits No Way On Earth A1 4:42 Piano, Organ – Louis Tillet*Written-By – Younger* There's No Time A2 3:32 Written-By – Younger* Another Sin A3 3:33 Written-By – Owen*, Dickson*, Fisher*, Younger* The March A4 5:28 Written-By – Owen*, Younger* The Burning Of Rome A5 5:14 Piano, Organ – Louis Tillet*Written-By – Younger* Afterburn B1 4:47 Written-By – Owen*, Younger* Circus Of Sour B2 3:56 Written-By – Owen*, Younger* Coming Apart B3 2:55 Written-By – Younger* Bed Of Nails B4 6:26 Written-By – Dickson*, Younger* Love's Underground B5 4:09 Piano, Organ – Louis Tillet*Written-By – Owen*, Dickson*, Fisher*, Younger* Companies, etc. Recorded At – Trafalgar Studios Mixed At – Trafalgar Studios Mastered At – EMI Studios 301 Published By – Marmara Publishing Phonographic Copyright (p) – Citadel Records Copyright (c) – Citadel Records Manufactured By – Iberofon, S.A. Printed By – Offset ALG, S.A. Credits Bass, Vocals – Jim Dickson Cover – Peter Simpson Drums – Nick Fisher Guitar, Piano, Organ – Charlie Owen Lead Vocals – Rob Younger Mastered By – Don Bartley Photography By [Cover Photo] – Jim Dickson Photography By [Other Photos] – Jim Dickson , Nick Fisher Producer – Rob Younger Recorded By, Mixed By – Alan Thorne Notes Recorded and mixed at Trafalgar Studios, Sydney, Australia January, 1989. -

{PDF EPUB} Grant & I Inside and Outside the Go

Read Ebook {PDF EPUB} Grant & I Inside and Outside the Go-Betweens by Robert Forster Grant & I review – Robert Forster writes moving, definitive portrait the Go-Betweens deserve. F ifty pages into this long-awaited memoir, songwriter, critic and author Robert Forster gets very meta. “If a film of Grant & I is ever made, it could start here,” he writes. It’s 1978, and he and Grant McLennan, the co-founders of the Go-Betweens, are driving from Brisbane to Sydney for the first time. After crossing the Tweed river into New South Wales, McLennan dashes into a shop, and emerges triumphantly waving a copy of Playboy, which was banned in Queensland at the time. Of course, this being the Go-Betweens, they’re reading it for the articles – in this instance, Bob Dylan’s first full-length interview in three years, which McLennan ecstatically reads to Forster as the car races past canefields on their left, Mount Warning on the right (“Cue thundercrack,” Forster says). The Go-Betweens always were the most self-referential of groups, as well as the most literate. Grant & I would make the most bookish of buddy films. That’s not to say they were square. “On many occasions dark rock bands would encounter the Go-Betweens expecting namby-pamby, book- besotted, cocoa-drinking wimps, to find themselves partied under the table. We were a rock’n’roll band,” Forster declares. Yet it’s both a strength and a weakness that this often very moving book avoids the cliched recounting of rock’n’roll excess – until those excesses inevitably begin to catch up with them.