Endometrial Response to Different Estrogens

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Estrone with Pipera- with an Anabolic Steroid and a Progestogen for Osteoporosis

Estradiol/Ethinylestradiol 2101 Estrapronicate (rINN) menopausal atrophic vaginitis and kraurosis vulvae. A dose of Estrapronicato; Estrapronicatum. Oestradiol 17-nicotinate 3- 500 micrograms may be given as a 0.01% or 0.1% cream or as a pessary; initial treatment may be given once daily, then reduced propionate. O to twice each week. NH CH3 Эстрапроникат Estriol has also been given orally for infertility (p.2080) caused HN C27H31NO4 = 433.5. by poor cervical penetration, in a dose of 0.25 to 1 mg daily on H CAS — 4140-20-9. days 6 to 15 of the menstrual cycle. O Estriol succinate has also been given orally in the treatment of HO HH menopausal disorders. The sodium succinate salt has been used S N parenterally in the treatment of haemorrhage and thrombocyto- O penia. O Preparations Pharmacopoeias. In Br. and US. BP 2008: Estriol Cream. BP 2008 (Estropipate). A white or almost white crystalline pow- Proprietary Preparations (details are given in Part 3) O O der. Very slightly soluble in water, in alcohol, in chloroform, and Arg.: Colpoestriol; Orgestriol; Austral.: Ovestin; Austria: Ortho-Gynest; in ether. H3C Ovestin; Styptanon; Belg.: Aacifemine; Ortho-Gynest; Braz.: Estriopax; Hormocervix; Hormoniol; Ovestrion; Styptanon; Chile: Ovestin; Sina- USP 31 (Estropipate). A white to yellowish-white fine crystal- pause; Vacidox; Cz.: Ortho-Gynest; Ovestin; Denm.: Ovestin; Fin.: Oves- line powder, odourless or may have a slight odour. Very slightly H tin; Pausanol; Fr.: Gydrelle; Physiogine; Trophicreme; Ger.: Cordes Estriol; soluble in water, in alcohol, in chloroform, and in ether; soluble Gynasan†; OeKolp; Oestro-Gynaedron M; Ortho-Gynest; Ovestin; Syna- 1 in 500 of warm alcohol; soluble in warm water. -

Download Product Insert (PDF)

PRODUCT INFORMATION Quinestrol Item No. 10006320 CAS Registry No.: 152-43-2 Formal Name: 3-(cyclopentyloxy)-19-norpregna- 1,3,5(10)-trien-20-yn-17α-ol Synonyms: Ethylnyl Estradiol-3-cyclopentyl ether, W 3566 MF: C25H32O2 FW: 3645 Purity: ≥98% UV/Vis.: λmax: 202, 281 nm Supplied as: A crystalline solid Storage: -20°C Stability: ≥2 years Information represents the product specifications. Batch specific analytical results are provided on each certificate of analysis. Laboratory Procedures Quinestrol is supplied as a crystalline solid. A stock solution may be made by dissolving the quinestrol in an organic solvent purged with an inert gas. Quinestrol is soluble in organic solvents such as ethanol, DMSO, and dimethyl formamide (DMF). The solubility of quinestrol in ethanol is approximately 20 mg/ml and approximately 30 mg/ml in DMSO and DMF. Quinestrol is sparingly soluble in aqueous buffers. For maximum solubility in aqueous buffers, should first be dissolved in DMSO and then diluted with the aqueous buffer of choice. Quinestrol has a solubility of approximately 0.5 mg/ml in a 1:1 solution of DMSO:PBS (pH 7.2) using this method. We do not recommend storing the aqueous solution for more than one day. Description Quinestrol is a synthetic estrogen that is effective in hormone replacement therapy.1,2 It is a 3-cyclopentyl ether of ethynyl estradiol. After gastrointestinal absorption, it is stored in adipose tissue, where it is slowly released and metabolized in the liver to its active form, ethynyl estradiol. Quinestrol has found limited use in suppressing lactation in postpartum women and, in combination with synthetic progestogens, as contraceptive therapy, although additional studies are needed for both applications. -

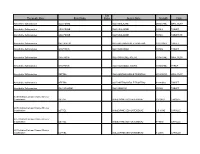

Therapeutic Class Brand Name P a Status Generic

P A Therapeutic Class Brand Name Status Generic Name Strength Form Absorbable Sulfonamides AZULFIDINE SULFASALAZINE 250MG/5ML ORAL SUSP Absorbable Sulfonamides AZULFIDINE SULFASALAZINE 500MG TABLET Absorbable Sulfonamides AZULFIDINE SULFASALAZINE 500MG TABLET DR Absorbable Sulfonamides BACTRIM DS SULFAMETHOXAZOLE/TRIMETHO 800-160MG TABLET Absorbable Sulfonamides GANTRISIN SULFISOXAZOLE 500MG TABLET Absorbable Sulfonamides GANTRISIN SULFISOXAZOLE ACETYL 500MG/5ML ORAL SUSP Absorbable Sulfonamides GANTRISIN SULFISOXAZOLE ACETYL 500MG/5ML SYRUP Absorbable Sulfonamides SEPTRA SULFAMETHOXAZOLE/TRIMETHO 200-40MG/5 ORAL SUSP Absorbable Sulfonamides SEPTRA SULFAMETHOXAZOLE/TRIMETHO 400-80MG TABLET Absorbable Sulfonamides SULFADIAZINE SULFADIAZINE 500MG TABLET ACE Inhibitor/Calcium Channel Blocker Combination LOTREL AMLODIPINE BESYLATE/BENAZ 10-20MG CAPSULE ACE Inhibitor/Calcium Channel Blocker Combination LOTREL AMLODIPINE BESYLATE/BENAZ 2.5-10MG CAPSULE ACE Inhibitor/Calcium Channel Blocker Combination LOTREL AMLODIPINE BESYLATE/BENAZ 5-10MG CAPSULE ACE Inhibitor/Calcium Channel Blocker Combination LOTREL AMLODIPINE BESYLATE/BENAZ 5-20MG CAPSULE P A Therapeutic Class Brand Name Status Generic Name Strength Form ACE Inhibitor/Calcium Channel Blocker Combination LOTREL AMLODIPINE BESYLATE/BENAZ 5-40MG CAPSULE ACE Inhibitor/Calcium Channel Blocker Combination LOTREL AMLODIPINE BESYLATE/BENAZ 10-40MG CAPSULE Acne Agents, Systemic ACCUTANE ISOTRETINOIN 10MG CAPSULE Acne Agents, Systemic ACCUTANE ISOTRETINOIN 20MG CAPSULE Acne Agents, Systemic ACCUTANE -

Postmenopausal Pharmacotherapy Newsletter

POSTMENOPAUSAL PHARMACOTHERAPY September, 1999 As Canada's baby boomers age, more and more women will face the option of Hormone Replacement Therapy (HRT). The HIGHLIGHTS decision can be a difficult one given the conflicting pros and cons. M This RxFiles examines the role and use of HRT, as well as newer Long term HRT carries several major benefits but also risks SERMS and bisphosphonates in post-menopausal (PM) patients. which should be evaluated on an individual and ongoing basis MContinuous ERT is appropriate for women without a uterus HRT MWomen with a uterus should receive progestagen (at least 12 HRT is indicated for the treatment of PM symptoms such as days per month or continuous low-dose) as part of their HRT vasomotor disturbances and urogenital atrophy, and is considered MLow-dose ERT (CEE 0.3mg) + Ca++ appears to prevent PMO primary therapy for prevention and treatment of postmenopausal MBisphosphinates (e.g. alendronate, etidronate) and raloxifene are osteoporosis (PMO).1 Contraindications are reviewed in Table 2. alternatives to HRT in treating and preventing PMO Although HRT is contraindicated in women with active breast or M"Natural" HRT regimens can be compounded but data is lacking uterine cancer, note that a prior or positive family history of these does not necessarily preclude women from receiving HRT.1 Comparative Safety: Because of differences between products, some side effects may be alleviated by switching from one product Estrogen Replacement Therapy (ERT) 2 to another, particularly from equine to plant sources or from oral to Naturally secreted estrogens include: topical (see Table 3 - Side Effects & Their Management). -

To See References

Longevity & Bioidentical Hormones Friedrich N, Haring R, Nauck M, et al. Mortality and serum insulin-like growth factor (IGF)-I and IGF binding protein 3 concentrations. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2009 May;94(5):1732-9. Malkin CJ, Pugh PJ, Morris PD, et al. Testosterone replacement in hypogonadal men with angina improves ischaemic threshold and quality of life. Heart. 2004 Aug;90(8):871-6. Besson A, Salemi S, Gallati S, et al. Reduced longevity in untreated patients with isolated growth hormone deficiency. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2003 Aug;88(8):3664- 7. Laughlin GA, Barrett-Connor E, Criqui MH, Kritz-Silverstein D. The prospective association of serum insulin-like growth factor I (IGF-I) and IGF-binding protein-1 levels with all cause and cardiovascular disease mortality in older adults: the Rancho Bernardo Study. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2004 Jan;89(1):114-120. Moffat SD, Zonderman AB, Metter EJ, et al. Free testosterone and risk for Alzheimer disease in older men. Neurology. 2004 Jan 27;62(2):188-193. Khaw KT, Dowsett M, Folkerd E, et al. Endogenous testosterone and mortality due to all causes, cardiovascular disease, and cancer in men: European prospective investigation into cancer in Norfolk (EPIC-Norfolk) Prospective Population Study. Circulation. 2007 Dec 4;116(23):2694-701. Malkin CJ, Pugh PJ, Jones RD, et al. The effect of testosterone replacement on endogenous inflammatory cytokines and lipid profiles in hypogonadal men. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2004 Jul;89(7):3313-3318. Selvin E, Feinleib M, Zhang L, et al. Androgens and diabetes in men: results from the Third National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES III). -

The Reactivity of Human and Equine Estrogen Quinones Towards Purine Nucleosides

S S symmetry Article The Reactivity of Human and Equine Estrogen Quinones towards Purine Nucleosides Zsolt Benedek †, Peter Girnt † and Julianna Olah * Department of Inorganic and Analytical Chemistry, Budapest University of Technology and Economics, Szent Gellért tér 4, H-1111 Budapest, Hungary; [email protected] (Z.B.); [email protected] (P.G.) * Correspondence: [email protected] † These authors contributed equally to this work. Abstract: Conjugated estrogen medicines, which are produced from the urine of pregnant mares for the purpose of menopausal hormone replacement therapy (HRT), contain the sulfate conjugates of estrone, equilin, and equilenin in varying proportions. The latter three steroid sex hormones are highly similar in molecular structure as they only differ in the degree of unsaturation of the sterane ring “B”: the cyclohexene ring in estrone (which is naturally present in both humans and horses) is replaced by more symmetrical cyclohexadiene and benzene rings in the horse-specific (“equine”) hormones equilin and equilenin, respectively. Though the structure of ring “B” has only moderate influence on the estrogenic activity desired in HRT, it might still significantly affect the reactivity in potential carcinogenic pathways. In the present theoretical study, we focus on the interaction of estrogen orthoquinones, formed upon metabolic oxidation of estrogens in breast cells with purine nucleosides. This multistep process results in a purine base loss in the DNA chain (depurination) and the formation of a “depurinating adduct” from the quinone and the base. The point mutations induced in this manner are suggested to manifest in breast cancer development in the long run. -

Enhanced Solubility and Dissolution Rate of Raloxifene Using Cycloencapsulation Technique

Journal of Analytical & Pharmaceutical Research Enhanced Solubility and Dissolution Rate of Raloxifene using Cycloencapsulation Technique Research Article Abstract Volume 2 Issue 5 - 2016 The aim of this study was to improve the water solubility of raloxifene by aqueous solution and solid state was evaluated by the phase solubility diagram, powdercomplexing X-ray it diffractometer,with sulphobutylether-β-cyclodextrin. Fourier-transform infrared Inclusion spectroscopy, complexation nuclear in magnetic resonance, scanning electron microscopy, hot stage microscopy and transmission electron microscopy. The inclusion complex behavior of raloxifene 1Department of Pharmaceutical Technology (Formulation), National Institute of Pharmaceutical Education and Research, classifiedand sulphobutylether-β-cyclodextrin as AL-type curve, indicating the were formation examined of 1:1 by stochiomatric molecular modelinginclusion India method. The phase solubility diagram with sulphobutylether-β-cyclodextrin was complex. The apparent solubility constants calculated from phase solubility 2 -1 Technology Development Center, National Institute of diagram was 753 M . Aqueous solubility and dissolution studies indicated that Pharmaceutical Education and Research, India the dissolution rates were remarkably increased in inclusion complex, compared 3Department of Pharmacoinformatics, National Institute of with the physical mixture and drug alone. In conclusion, inclusion complexation Pharmaceutical Education and Research, India 4 solubility and dissolution rate -

Exposure to Female Hormone Drugs During Pregnancy

British Journal of Cancer (1999) 80(7), 1092–1097 © 1999 Cancer Research Campaign Article no. bjoc.1998.0469 Exposure to female hormone drugs during pregnancy: effect on malformations and cancer E Hemminki, M Gissler and H Toukomaa National Research and Development Centre for Welfare and Health, Health Services Research Unit, PO Box 220, 00531 Helsinki, Finland Summary This study aimed to investigate whether the use of female sex hormone drugs during pregnancy is a risk factor for subsequent breast and other oestrogen-dependent cancers among mothers and their children and for genital malformations in the children. A retrospective cohort of 2052 hormone-drug exposed mothers, 2038 control mothers and their 4130 infants was collected from maternity centres in Helsinki from 1954 to 1963. Cancer cases were searched for in national registers through record linkage. Exposures were examined by the type of the drug (oestrogen, progestin only) and by timing (early in pregnancy, only late in pregnancy). There were no statistically significant differences between the groups with regard to mothers’ cancer, either in total or in specified hormone-dependent cancers. The total number of malformations recorded, as well as malformations of the genitals in male infants, were higher among exposed children. The number of cancers among the offspring was small and none of the differences between groups were statistically significant. The study supports the hypothesis that oestrogen or progestin drug therapy during pregnancy causes malformations among children who were exposed in utero but does not support the hypothesis that it causes cancer later in life in the mother; the power to study cancers in offspring, however, was very low. -

Title 16. Crimes and Offenses Chapter 13. Controlled Substances Article 1

TITLE 16. CRIMES AND OFFENSES CHAPTER 13. CONTROLLED SUBSTANCES ARTICLE 1. GENERAL PROVISIONS § 16-13-1. Drug related objects (a) As used in this Code section, the term: (1) "Controlled substance" shall have the same meaning as defined in Article 2 of this chapter, relating to controlled substances. For the purposes of this Code section, the term "controlled substance" shall include marijuana as defined by paragraph (16) of Code Section 16-13-21. (2) "Dangerous drug" shall have the same meaning as defined in Article 3 of this chapter, relating to dangerous drugs. (3) "Drug related object" means any machine, instrument, tool, equipment, contrivance, or device which an average person would reasonably conclude is intended to be used for one or more of the following purposes: (A) To introduce into the human body any dangerous drug or controlled substance under circumstances in violation of the laws of this state; (B) To enhance the effect on the human body of any dangerous drug or controlled substance under circumstances in violation of the laws of this state; (C) To conceal any quantity of any dangerous drug or controlled substance under circumstances in violation of the laws of this state; or (D) To test the strength, effectiveness, or purity of any dangerous drug or controlled substance under circumstances in violation of the laws of this state. (4) "Knowingly" means having general knowledge that a machine, instrument, tool, item of equipment, contrivance, or device is a drug related object or having reasonable grounds to believe that any such object is or may, to an average person, appear to be a drug related object. -

Effects of Histone Deacetylase Inhibitors on Estradiol-Induced Proliferation and Hyperplasia Formation in the Mouse Uterus

539 Effects of histone deacetylase inhibitors on estradiol-induced proliferation and hyperplasia formation in the mouse uterus Andrei G Gunin, Irina N Kapitova and Nina V Suslonova Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology, Medical School Chuvash State University, PO Box 86, 428034, Cheboksary, Russia (Requests for offprints should be addressed to A G Gunin; Email: [email protected]) Abstract It is suggested that estrogen hormones recruit mechanisms of mitotic and bromodeoxyuridine-labelled cells in luminal controlling histone acetylation to bring about their effects and glandular epithelia, in stromal and myometrial cells. in the uterus. However, it is not known how the level of Levels of estrogen receptor- and progesterone receptors histone acetylation affects estrogen-dependent processes in in uterine epithelia, stromal and myometrial cells were the uterus, especially proliferation and morphogenetic decreased in mice treated with estradiol and trichostatin A changes. Therefore, this study examined the effects of or sodium butyrate. Expression of -catenin in luminal histone deacetylase blockers, trichostatin A and sodium and glandular epithelia was attenuated in mice treated butyrate, on proliferative and morphogenetic reactions in with estradiol with trichostatin A or sodium butyrate. Both the uterus under long-term estrogen treatment. Ovari- histone deacetylase inhibitors have similar unilateral effects; ectomized mice were treated with estradiol dipropionate however the action of trichostatin A was more expressed (4 µg per 100 g; s.c., once a week) or vehicle and tricho- than that of sodium butyrate. Thus, histone deacetylase statin A (0·008 mg per 100 g; s.c., once a day) or sodium inhibitors exert proliferative and morphogenetic effects of butyrate (1% in drinking water), or with no additional estradiol. -

UNASYN® (Ampicillin Sodium/Sulbactam Sodium)

NDA 50-608/S-029 Page 3 UNASYN® (ampicillin sodium/sulbactam sodium) PHARMACY BULK PACKAGE NOT FOR DIRECT INFUSION To reduce the development of drug-resistant bacteria and maintain the effectiveness of UNASYN® and other antibacterial drugs, UNASYN should be used only to treat or prevent infections that are proven or strongly suspected to be caused by bacteria. DESCRIPTION UNASYN is an injectable antibacterial combination consisting of the semisynthetic antibiotic ampicillin sodium and the beta-lactamase inhibitor sulbactam sodium for intravenous and intramuscular administration. Ampicillin sodium is derived from the penicillin nucleus, 6-aminopenicillanic acid. Chemically, it is monosodium (2S, 5R, 6R)-6-[(R)-2-amino-2-phenylacetamido]- 3,3-dimethyl-7-oxo-4-thia-1-azabicyclo[3.2.0]heptane-2-carboxylate and has a molecular weight of 371.39. Its chemical formula is C16H18N3NaO4S. The structural formula is: COONa O CH3 N CH O 3 NH S NH2 Sulbactam sodium is a derivative of the basic penicillin nucleus. Chemically, sulbactam sodium is sodium penicillinate sulfone; sodium (2S, 5R)-3,3-dimethyl-7-oxo-4-thia 1-azabicyclo [3.2.0] heptane-2-carboxylate 4,4-dioxide. Its chemical formula is C8H10NNaO5S with a molecular weight of 255.22. The structural formula is: NDA 50-608/S-029 Page 4 COONa CH3 O N CH3 S O O UNASYN, ampicillin sodium/sulbactam sodium parenteral combination, is available as a white to off-white dry powder for reconstitution. UNASYN dry powder is freely soluble in aqueous diluents to yield pale yellow to yellow solutions containing ampicillin sodium and sulbactam sodium equivalent to 250 mg ampicillin per mL and 125 mg sulbactam per mL. -

Estrogen Metabolism in the Human Estrogen Metabolism in the Human

ENE PURRE: ESTROGEN METABOLISM IN THE HUMAN ESTROGEN METABOLISM IN THE HUMAN A THESIS BY ENE PURRE SUBMITTED TO THE FACULTY OF GRADUATE STUDIES AND RESEARCH IN PARTIAL FULFILMENT FOR THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF SCIENCE McGILL UNIVERSITY MONTREAL, CANADA. DEPARTMENT OF EXPERIMENTAL MEDICINE AUGUST 1965 TABLE OF CONTENTS Page No. I INTRODUCTION A. Early history and isolation of the e strogens 2 B. Metabolism of the estrogens 4 1. Biogenesis 4 2. Metabolism 6 3. Degradation 14 4. Conjugation 15 c. Altered states of estrogen metabolism 18 Purpose of the Investigation II MATERIALS AND METHODS 25 Materials I Radioactive compounds 25 II Non-radioactive compounds 25 Ill Enzymes 26 IV Reagents 26 Methods I Purification of radioactive steroids 30 II Preparation of non-radioactive standards 31 III Spectophotometric and f1uorimetric readings 31 IV Counting methods 32 V Enzyme assays 33 VI Injections 33 VII Collection of urine 34 VIII Hydrolysis and extraction of urines 34 IX Assay of estrone, estradiol-17 f.:' and estriol 36 X Attempts at separa ting ring 011( keto1s 3 7 XI Assay of ring D..: ketols in the urine 39 XII Recrysta1lization studies 40 ---------------···---- TABLE OF CONTENTS (cont.) Page No._ Ill RESULTS Section I - Studies with control subjects and those with myocardial infarction 41 Section II- A. Recovery of 16~-hydroxyestrone and 16-ketoestradiol-17~ from toluene/ propylene glycol system 50 B. Pre 1 imi nary study on urinary ring De>< ketols 51 c. Urinary ring D<K ke to 1 s in nonnal males 53 D. Studies of the excretion and metabolism of eight estrogen metabolites from urine 59 IV DISCUSSION 71 SUMMARY 87 BIBLIOGRAPHY 89 • LIST OF FIGURES Figure No.