Management Practices and Busineiss Development in Pakistan, 1950-1988

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

NJI Title Annual 2008.FH10

CONTENTS Corporate Information 2 Vision & Mission 3 Directors Report to the Shareholders 4 Key Operating and Financial Highlights 9 Statement of Compliance with the Code of Corporate Governance 10 Review Report to the Members 12 Auditors Report to the Members 13 Balance Sheet 14 Profit & Loss Account 16 Statement of Changes in Equity 17 Cash Flow Statement 18 Revenue Account 19 Statement of Premiums 20 Statement of Claims 21 Statement of Expenses 22 Statement of Investment Income 23 Notes to the Financial Statements 24 Statement of Directors 52 Statement of Appointed Actuary 52 Pattern of Shareholding 53 Compliance Status of the Code of Corporate Governance 55 Notice of Annual General Meeting 57 Proxy Form CORPORATE INFORMATION BOARD OF DIRECTORS Masood Noorani Chairman Javed Ahmed Chief Executive Officer / Managing Director Towfiq H. Chinoy Director Sultan Allana Director Shahid Mahmood Loan Director Xavier Gwenael Lucas Director John Joseph Metcalf Director BOARD COMMITTEES MANAGEMENT COMMITTEES AUDIT CLAIMS Xavier Gwenael Lucas Chairman Javed Ahmed Chairman Shahid Mahmood Loan Member Manzoor Ahmed Member John Joseph Metcalf Member Zahid Barki Member/Secretary FINANCE & INVESTMENT Masood Noorani Chairman REINSURANCE Javed Ahmed Member Javed Ahmed Chairman Shahid M. Loan Member Zahid Barki Member John Joseph Metcalf Member Sana Hussain Member/Secretary Manzoor Ahmed Member/Secretary HUMAN RESOURCE UNDERWRITING Towfiq H. Chinoy Chairman Javed Ahmed Chairman Masood Noorani Member Syed Ali Ameer Rizvi Member John Joseph Metcalf Member Zahid Barki Member/Secretary TECHNICAL COMPANY SECRETARY John Joseph Metcalf Chairman Manzoor Ahmed Javed Ahmed Member Xavier Gwenael Lucas Member CHIEF INTERNAL AUDITOR Adeel Ahmed Khan HEAD OFFICE AUDITORS 74/1-A, Lalazar, M. -

Pashto, Waneci, Ormuri. Sociolinguistic Survey of Northern

SOCIOLINGUISTIC SURVEY OF NORTHERN PAKISTAN VOLUME 4 PASHTO, WANECI, ORMURI Sociolinguistic Survey of Northern Pakistan Volume 1 Languages of Kohistan Volume 2 Languages of Northern Areas Volume 3 Hindko and Gujari Volume 4 Pashto, Waneci, Ormuri Volume 5 Languages of Chitral Series Editor Clare F. O’Leary, Ph.D. Sociolinguistic Survey of Northern Pakistan Volume 4 Pashto Waneci Ormuri Daniel G. Hallberg National Institute of Summer Institute Pakistani Studies of Quaid-i-Azam University Linguistics Copyright © 1992 NIPS and SIL Published by National Institute of Pakistan Studies, Quaid-i-Azam University, Islamabad, Pakistan and Summer Institute of Linguistics, West Eurasia Office Horsleys Green, High Wycombe, BUCKS HP14 3XL United Kingdom First published 1992 Reprinted 2004 ISBN 969-8023-14-3 Price, this volume: Rs.300/- Price, 5-volume set: Rs.1500/- To obtain copies of these volumes within Pakistan, contact: National Institute of Pakistan Studies Quaid-i-Azam University, Islamabad, Pakistan Phone: 92-51-2230791 Fax: 92-51-2230960 To obtain copies of these volumes outside of Pakistan, contact: International Academic Bookstore 7500 West Camp Wisdom Road Dallas, TX 75236, USA Phone: 1-972-708-7404 Fax: 1-972-708-7433 Internet: http://www.sil.org Email: [email protected] REFORMATTING FOR REPRINT BY R. CANDLIN. CONTENTS Preface.............................................................................................................vii Maps................................................................................................................ -

Star Textile Mills LTD. A-41 SITE, Karachi

S# M # Company Name Mailing Address Tel # Fax # Name of Authorized Representative Designation Mobile-1 Email-1 NIC # NTN ST # 1 0026 Star Textile Mills LTD. A-41 SITE, Karachi. 32561127-29, 3251149 32580836 Mian MUHAMMAD ZAHID Law Consultant 0300-9243820 [email protected] 42201-6422669-5 069845-9 02-02-5111-019-19 2 0028 A. B. (Al-Hashmi Brothers) (PVT) LTD. H-6 SITE, Karachi. 32572963 Syed Shakir Hashmi Director 0333-2283020 [email protected] 42000-7647196-1 0704163-2 02-02-2811-003-55 3 0041 KOHINOOR CHEMICAL CO. (PVT) LIMITED 9TH FLOOR, TIBBET CENTRE, M. A. JINNAH ROAD, KHI 32564553, 32563425, 32563730, 32570144-6, 32571127 Mr. Aslam Allawala 0300-2150567 [email protected] 0710919-9 02-06-3302-001-91 4 0043 AHMED FOODS (PVT) LTD. D-112, AHMED HOUSE, SITE, KARACHI 111-987-789, 32563520-4 32578196 SYED HASIB AHMED Executive Director 0300-8269430 [email protected] 42101-0715400-3 0704016-4 02-06-2100-002-37 5 0046 HELIX PHARMA (PVT) LIMITED A-56, SITE, KARACHI 32562507, 32563856, 32563882, 32570182-3 32564393 TANWEER AHMED GM-HR & Admin 0333-0202206 [email protected] 42201-0793883-7 0710606-8 11-01-7010-002-46 6 0049 INDUS PENCIL INDUSTRIES (PVT) LIMITED B-54, SITE, KARACHI 32573214-7 32564931 MR. NAEEM AKHTAR YOUSUF 0300-8221852 [email protected] 42201-0468514-1 0710696-3 02-02-3208-016-64 7 0052 EXIDE PAKISTAN LIMITED A-44, SITE, Karachi 32578061-4, 32574610 32591679 SYED ZULQARNAIN SHAH GM 0333-2244702 [email protected] 42000-0479156-9 0676659-5 02-01-8507-001-64 8 0061 PAKISTAN CABLES LIMITED B-21, SITE, KARACHI 32561170-5 32564614 Aslam Sadruddin 0300-9227015 [email protected] 42301-4759734-3 0711509-1 02-02-7605-001-82 9 0067 Pakistan Paper Products Limited D-58 SITE, Karachi. -

World Bank Document

INTRODUCTION ______________________________________________________________________ The International Finance Corporation (IFC), part of the World Bank Group, is in the business of reducing Public Disclosure Authorized poverty and encouraging economic development in poorer countries through the private sector. IFC carries out this mandate primarily by investing in a wide variety of private projects in developing countries, always investing with other sponsors and financial institutions. These projects are selected first and foremost for their ability to contribute to economic growth and development. Obviously, to contribute effectively to development in the long run, IFC’s private sector projects must also be financially successful. Companies that are not financially viable clearly cannot contribute to development. IFC and its partners are, therefore, profit-seeking and take on the same risks as any private sector investor. Thus all IFC projects are screened not only for their likely contributions to development but also for the likelihood of their financial success. This screening, as it happens, is not simple. Projects have complicated effects on an economy and, more generally, on society as a whole. Usually, for example, projects directly create productive employment and better jobs in the business being financed. But employment effects are spread much more widely, as Public Disclosure Authorized increased business goes to suppliers or retailers and as new business is created elsewhere in the economy by employees spending their wages and salaries. There are many such effects, each difficult, if not impossible, to isolate from the investment. Because of these difficulties, most of these effects are not normally included in project analysis or decisionmaking but are nonetheless important in a development context. -

Argentina: ''Non- Smokers' Dictatorship'' USA: Make Health Insurance Include Cessation Help, Says Poll

6 News analysis....................................................................................... Tob Control: first published as on 25 February 2004. Downloaded from socioeconomic classes—professionals, challenges the bans on smoking in Argentina: ‘‘non- government officials, and students— closed environments. and sells approximately 10 000 copies However, the Veintitre´s article’s com- smokers’ dictatorship’’ each week. It is advertised on television. parison of the smoke-free movement On 2 October last year, just five days A well known journalist and former with the Nazis is a classic example of the after Argentina signed the Framework director of the magazine, one of the favourite tobacco industry strategy of Convention on Tobacco Control (FCTC), people whose views against tobacco con- trying to position those who work for the magazine Veintitre´s (‘‘Twenty-three’’) trol were quoted in the article, also smoke-free environments as members published a note on smoke-free envir- conducts a popular political news of an extremist movement. Tobacco onments. The main story of the maga- programme on television together with control activists around the world zine was illustrated on the front cover some of the staff of Veintitre´s. During should be aware of this strategy, and using the swastika under the title ‘‘The the show, and most unusually for be prepared to respond with the appro- non-smokers’ dictatorship’’. television, he smokes frequently—he priate arguments. Smoke-free environments are close to obtained a privileged contract to be the JAVIER SAIMOVICI becoming a reality for Argentineans, not only person allowed to smoke on the Unio´n Anti-Taba´quica Argentina, ‘‘UATA’’, only as a result of the signing of the studio set. -

Directors Training Programme Module 1: September 18 - 19, 2015 Module II: October 2 - 3, 2015 Serial # Participant Name Company Name Email City Education Status

Enhancing Board Effectiveness - Directors Training Programme Module 1: September 18 - 19, 2015 Module II: October 2 - 3, 2015 Serial # Participant Name Company Name Email City Education Status 1 Muhammad Usman Hanif Fatima Group (Reliance Sacks) [email protected] Lahore Cantt Chartered Accountancy Certified Director 2 Firasat Ali Habib Metropolitan Bank Limited Karachi [email protected] Karachi MA Agricultural Economics Certified Director 3 Haider Zaidi Haris Enterprises [email protected] Islamabad BE Certified Director 4 Irshad Ali S. Kassim Karam Ceramics Limited [email protected] Karachi Master of Business Administration Certified Director 5 Dr. Khurram Tariq Kay & Emms (Private) Limited [email protected] Faisalabad MBBS Certified Director 6 Zahid Wazir Khan KIPS [email protected] Lahore B.Sc Mechanical Engg Certified Director 7 Muhammad Samiullah Siddiqui Linde Pakistan Limited. [email protected] Karachi Bachelor of Commerce Certified Director 8 Nasir Ali Zia Masood Textile Mills Limited [email protected] Faisalabad MPA Certified Director Fellow member of Institute of Chartered 9 Kamran Nishat Muller & Phipps Pakistan (Private)Limited [email protected] Karachi Certified Director Accountants of Pakistan (FCA) Pak Brunei - Primus Investment Management Company 10 Ahmed Ateeq [email protected] Karachi Master Of Business Administration Certified Director Limited 11 Masood Tahir Pak Elektron Limited Lahore FCA Certified Director 12 Awais Yasin Punjab Saaf Pani Co [email protected] Lahore ACMA/LLB Certified Director 13 Mohammad Kashif Punjab Saaf Pani Co [email protected] Lahore M. Sc. Certified Director 14 Irfan Rahman Malik Rahman Sarfaraz Rahim Iqbal Rafiq, Chartered Accountants [email protected] Lahore NA Certified Director 15 Mohammad Azeem Rashid RS Equities (Private) Limited [email protected] Lahore Bachelors in Business Adminstration Certified Director 16 Abid Ur Rehman Samsons Group [email protected] Lahore Doctor of Medicine Certified Director 17 M. -

Geology of the Southern Gandghar Range and Kherimar Hills, Northern Pakistan

AN ABSTRACT OF THE THESIS OF Michael D. Hylland for the degree of Master of Science in Geology presented on May 3. 1990 Title: Geology of the Southern Gandghar Range and Kherimar Hills. Northern Pakistan Abstract approved: RobeS. Yeats The Gandghar Range and Kherimar Hills, located in the Hill Ranges of northern Pakistan, contain rocks that are transitional between unmetarnorphosed foreland-basin strata to the south and high-grade metamorphic and plutonic rocks to the north. The southern Gandghar Range is composed of a succession of marine strata of probable Proterozoic age, consisting of a thick basal argillaceous sequence (Manki Formation) overlain by algal limestone and shale (Shahkot, Utch Khattak, and Shekhai formations). These strata are intruded by diabase dikes and sills that may correlate with the Panjal Volcanics. Southern Gandghar Range strata occur in two structural blocks juxtaposed along the Baghdarra fault. The hanging wall consists entirely of isoclinally-folded Manki Formation, whereas the footwall consists of the complete Manki-Shekhai succession which has been deformed into tight, northeast-plunging, generally southeast (foreland) verging disharmonic folds. Phyllite near the Baghdarra fault displays kink bands, a poorly-developed S-C fabric, and asymmetric deformation of foliation around garnet porphyroblasts. These features are consistent with conditions of dextral shear, indicating reverse-slip displacement along the fault. South of the Gandghar Range, the Panjal fault brings the Gandghar Range succession over the Kherimar Hills succession, which is composed of a basal Precambrian arenaceous sequence (Hazara Formation) unconformably overlain by Jurassic limestone (Samana Suk Formation) which in turn is unconformably overlain by Paleogene marine strata (Lockhart Limestone and Patala Formation). -

Newsletter 74

Quarterly Newsletter Central Depository Company A RICH NATION Gems Mining Gold Mining Salt Mining Coal Mining Nature has bestowed Pakistan with generous treasures of size emeralds in South Asia. Recently, a 2500 year old earring gemstones which make Pakistan prominent in the mineral was found in France to have an emerald that originated most world. The world's most desired colored gemstones, such as likely in these Mingora mines. Sometimes locals have also Ruby, Emerald, Sapphire, Topaz, Aquamarine, Peridot, found this gemstone in the Swat River. Amethyst, Morganite, Zoisite, Spinel, Sphene, and Tourmaline, are found in Pakistan. The northern and northwestern parts of Being the sole depository in Pakistan, established and Pakistan are shrouded by the three world-famous mountain functioning since the last two decades, CDC has a scintillating ranges of Hindukush, Himalaya, and Karakorum. In these prominence in the Capital Market of Pakistan. It is undoubtedly mountains are found nearly all the minerals Pakistan currently a precious gemstone of the Capital Market infrastructure, with offers to the world market, including these precious gemstones. an excellent reputation and legacy of upholding the principles of reliability, trust and integrity. CDC’s perseverance to One of these enthusiastically glittering gems, Swat Emerald, is maintain and ensure complete investor confidence and its hexagonal in shape and has transparent, deep sea green colour. providence to stay abreast with technological advancement The Mingora mines in Swat Valley host some of the best, small makes it a unique gemstone of the Pakistan Capital Market. Head Office: Lahore Branch: CDC House, 99-B, Block ‘B’, S.M.C.H.S., Main Mezzanine Floor, South Tower, LSE Plaza, 19 Shahrah-e-Faisal, Karachi - 74400. -

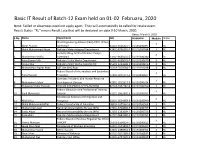

Basic IT Result of Batch 12

Basic IT Result of Batch-12 Exam held on 01-02 Februaru, 2020 Note: Failled or absentees need not apply again. They will automatically be called for retake exam. Result Status "RL" means Result Late that will be declared on date 9-10 March, 2020. Dated: March 5, 2020 S.No Name Department NIC Studentid Module Status Chief Engineering Adviser (CEA) /CFFC Office, 3 1 Abrar Hussain Islamabad 61101-5666325-7 VU191200097 RL 2 Malik Muhammad Ahsan Pakistan Meteorological Department 42401-8756355-7 VU191200184 3 RL Forestry Wing, M/O of Climate Change, 3 3 Muhammad Shafiq Islamabad 13101-3645024-5 VU191200280 RL 4 Asim Zaman Virk Pakistan Public Works Department 61101-4055043-7 VU191200670 3 RL 5 Rasool Bux Pakistan Public Works Department 45302-1434648-1 VU191200876 3 RL 6 Muhammad Asghar Khan S&T Dte GHQ Rwp 55103-7820568-7 VU191201018 3 RL Federal Board of Intermediate and Secondary 3 7 Tariq Hussain Education 37405-0231137-3 VU191200627 RL Overseas Pakistanis and Human Resource 3 8 Muhammad Zubair Development Division 42301-0211817-3 VU191200624 RL 9 Khaawaja Shabir Hussain CCD-VIII PAK PWD G-9/1 ISLAMABAD 82103-1652182-9 VU191200700 3 RL Federal Education and Professional Training 3 10 Sajid Mehmood Division 61101-1862402-9 VU191200933 RL Directorate General of Immigration and 3 11 Allah Ditta Passports 61101-6624393-9 VU191200040 RL 12 Malik Muhammad Afzal Federal Directorate of Education 38302-1075962-9 VU191200509 3 RL 13 Muhammad Asad National Accountability Bureau (KPk) 17301-6704686-5 VU191200757 3 RL 14 Sadiq Akbar National Accountability -

The Mirage of Power, by Mubashir Hasan

The Mirage of Power AN ENQUIRY INTO THE BHUTTO YEARS 1971-1977 BY MUBASHIR HASAN Reproduced By: Sani H. Panhwar Member Sindh Council PPP. CONTENTS About the Author .. .. .. .. .. .. i Preface .. .. .. .. .. .. .. ii Acknowledgements .. .. .. .. .. v 1. The Dramatic Takeover .. .. .. .. .. 1 2. State of the Nation .. .. .. .. .. .. 14 3. Meeting the Challenges (1) .. .. .. .. 22 4. Meeting the Challenges (2) .. .. .. .. 43 5. Restructuring the Economy (1) .. .. .. .. 64 6. Restructuring the Economy (2) .. .. .. .. 85 7. Accords and Discords .. .. .. .. 100 8. All Not Well .. .. .. .. .. .. 120 9. Feeling Free .. .. .. .. .. .. 148 10. The Year of Change .. .. .. .. .. 167 11. All Power to the Establishment .. .. .. .. 187 12. The Losing Battle .. .. .. .. .. .. 199 13. The Battle Lost .. .. .. .. .. .. 209 14. The Economic Legacy .. .. .. .. .. 222 Appendices .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. 261 ABOUT THE AUTHOR Dr. Mubashir Hasan is a well known figure in both academic and political circles in Pakistan. A Ph.D. in civil engineering, he served as an irrigation engineer and taught at the engineering university at Lahore. The author's formal entry into politics took place in 1967 when the founding convention of the Pakistan Peoples' Party was held at his residence. He was elected a member of the National Assembly of Pakistan in 1970 and served as Finance Minister in the late Prime Minister Zulfikar Ali Bhutto's Cabinet from 1971-1974. In 1975, he was elected Secretary General of the PPP. Following the promulgation of martial law in 1977, the author was jailed for his political beliefs. Dr. Hasan has written three books, numerous articles, and has spoken extensively on social, economic and political subjects: 2001, Birds of the Indus, (Mubashir Hasan, Tom J. -

Annual Report 2019 Managed and Controlled by Treet Holdings Limited

FIRST TREET MANUFACTURING MODARABA | Annual Report 2019 Managed and Controlled by Treet Holdings Limited ANNUAL REPORT 2019 TREET GROUP OF COMPANIES First Treet ftmm.com.pk Manufacturing Modaraba 1 2 02 34 Company Auditors’ Report to the Information Certificate-holders 35 03 Balance Directors’ Sheet Profile 36 06 Profit and Mission, Vision Loss Account Statements 37 07 Statement of Chairpersons’ Comprehensive Income Review 38 CONTENTS 08 Cash Flow Directors’ Statement Report 39 22 Statement of Changes in Directors’ Equity Report Urdu 40 23 Notes to the Statement of Ethics Financial Statements and Business Practices 79 28 Pattern of Statement of Compliance Certificate-holding with Code of Corporate Governance 80 Key Operating 31 Financial Data Independent Auditors’ Review Report 81 Notice of 13th Annual 32 Review Meeting Annual Shari’ah Advisor’s Report Company Information BOARD OF DIRECTORS: Dr. Mrs. Niloufer Qasim Mahdi Chairperson / Non-Executive Director Syed Shahid Ali Chief Executive Officer Syed Sheharyar Ali Non-Executive Director Mr. Imran Azim Non-Executive Director Mr. Munir Karim Bana Non-Executive Director Mr. Saulat Said Non-Executive Director Muhammad Shafique Anjum Non-Executive Director Dr. Salman Faridi Independent Director AUDIT COMMITTEE: Dr. Salman Faridi Chairman/Member Syed Sheharyar Ali Member Mr. Imran Azim Member Mr. Munir K. Bana Member Rana Shakeel Shaukat Secretary CHIEF ACCOUNTANTS: Mr. Sajjad Haider Khan Modaraba Mr. Muhammad Zubair Modaraba Company COMPANY SECRETARY: Rana Shakeel Shaukat EXTERNAL AUDITORS: -

Memon Welfare Society Newsletter February 2015

February 2015 Memon Welfare Society Newsletter إﻧﺎ ﷲ وإﻧﺎ إﻟﻴﻪ راﺟﻌﻮن Issue No. 68 King Abdullah Passed Away Patrons: His Majesty King Salman Bin Abdel Aziz M.Iqbal Advani Dr. Hamid A.Khader Munaf A.S.Bakhshi Mohammed I. Badi Dr. Mohammed Umer Chapra Kaleem A. Naviwala addressing the guests of MASA Grand Dinner. Dr.Iqbal Musani, Office Bearers: former president MASA is sitting with him President: To God We Belong and Indeed to Him Arif A.M. Memon we shall Return,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,. Vice Presidents: Younus Habib Goli & Custodian of the Two Holy Mosques King Abdullah Bin Abdelaziz died on rd Mansoor A.R.Shivani Friday 23 January 2015 following a short illness. Crown Prince Salman Bin Abdelaziz has been named the new king with Prince Muqrin as crown General Secretary: Tayyab K. Moosani prince, according to a Royal Court statement. (Arab News) Joint Secretary: Dear Brothers and Sisters, A.Rashid Kasmani Assalamo Alaikum WRWB Treasurer: th Shoaib Sikander While preparing 68 Issue of MASA Newsletter, we were shocked to lean above mentioned sad and tragic news. We sincerely offer our deepest condolences to each and every Saudi Brothers and share their grief. Let us go through the feelings of couple of great leaders of world which is Member Advisory: in fact feeling of most of the people: Dr.Iqbal Musani Irfan Kolsawala “I am deeply saddened to hear of the death of the Custodian of the Two Holy Mosques, His M.Younus A.Sattar Majesty King Abdullah bin Abdul Aziz Al‐Saud. He will be remembered for his long years of service to the Kingdom, for his commitment to peace and for strengthening understanding M.