Starfield AC

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Pr-Dvd-Holdings-As-Of-September-18

CALL # LOCATION TITLE AUTHOR BINGE BOX COMEDIES prmnd Comedies binge box (includes Airplane! --Ferris Bueller's Day Off --The First Wives Club --Happy Gilmore)[videorecording] / Princeton Public Library. BINGE BOX CONCERTS AND MUSICIANSprmnd Concerts and musicians binge box (Includes Brad Paisley: Life Amplified Live Tour, Live from WV --Close to You: Remembering the Carpenters --John Sebastian Presents Folk Rewind: My Music --Roy Orbison and Friends: Black and White Night)[videorecording] / Princeton Public Library. BINGE BOX MUSICALS prmnd Musicals binge box (includes Mamma Mia! --Moulin Rouge --Rodgers and Hammerstein's Cinderella [DVD] --West Side Story) [videorecording] / Princeton Public Library. BINGE BOX ROMANTIC COMEDIESprmnd Romantic comedies binge box (includes Hitch --P.S. I Love You --The Wedding Date --While You Were Sleeping)[videorecording] / Princeton Public Library. DVD 001.942 ALI DISC 1-3 prmdv Aliens, abductions & extraordinary sightings [videorecording]. DVD 001.942 BES prmdv Best of ancient aliens [videorecording] / A&E Television Networks History executive producer, Kevin Burns. DVD 004.09 CRE prmdv The creation of the computer [videorecording] / executive producer, Bob Jaffe written and produced by Donald Sellers created by Bruce Nash History channel executive producers, Charlie Maday, Gerald W. Abrams Jaffe Productions Hearst Entertainment Television in association with the History Channel. DVD 133.3 UNE DISC 1-2 prmdv The unexplained [videorecording] / produced by Towers Productions, Inc. for A&E Network executive producer, Michael Cascio. DVD 158.2 WEL prmdv We'll meet again [videorecording] / producers, Simon Harries [and three others] director, Ashok Prasad [and five others]. DVD 158.2 WEL prmdv We'll meet again. Season 2 [videorecording] / director, Luc Tremoulet producer, Page Shepherd. -

January 27, 2009 (XVIII:3) Samuel Fuller PICKUP on SOUTH STREET (1953, 80 Min)

January 27, 2009 (XVIII:3) Samuel Fuller PICKUP ON SOUTH STREET (1953, 80 min) Directed and written by Samuel Fuller Based on a story by Dwight Taylor Produced by Jules Schermer Original Music by Leigh Harline Cinematography by Joseph MacDonald Richard Widmark...Skip McCoy Jean Peters...Candy Thelma Ritter...Moe Williams Murvyn Vye...Captain Dan Tiger Richard Kiley...Joey Willis Bouchey...Zara Milburn Stone...Detective Winoki Parley Baer...Headquarters Communist in chair SAMUEL FULLER (August 12, 1912, Worcester, Massachusetts— October 30, 1997, Hollywood, California) has 53 writing credits and 32 directing credits. Some of the films and tv episodes he directed were Street of No Return (1989), Les Voleurs de la nuit/Thieves After Dark (1984), White Dog (1982), The Big Red One (1980), "The Iron Horse" (1966-1967), The Naked Kiss True Story of Jesse James (1957), Hilda Crane (1956), The View (1964), Shock Corridor (1963), "The Virginian" (1962), "The from Pompey's Head (1955), Broken Lance (1954), Hell and High Dick Powell Show" (1962), Merrill's Marauders (1962), Water (1954), How to Marry a Millionaire (1953), Pickup on Underworld U.S.A. (1961), The Crimson Kimono (1959), South Street (1953), Titanic (1953), Niagara (1953), What Price Verboten! (1959), Forty Guns (1957), Run of the Arrow (1957), Glory (1952), O. Henry's Full House (1952), Viva Zapata! (1952), China Gate (1957), House of Bamboo (1955), Hell and High Panic in the Streets (1950), Pinky (1949), It Happens Every Water (1954), Pickup on South Street (1953), Park Row (1952), Spring (1949), Down to the Sea in Ships (1949), Yellow Sky Fixed Bayonets! (1951), The Steel Helmet (1951), The Baron of (1948), The Street with No Name (1948), Call Northside 777 Arizona (1950), and I Shot Jesse James (1949). -

![Blog # 37] Monday, September 22 @ 8:44 Am PDT [Autumn Equinox]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/2239/blog-37-monday-september-22-8-44-am-pdt-autumn-equinox-1112239.webp)

Blog # 37] Monday, September 22 @ 8:44 Am PDT [Autumn Equinox]

FILM SCORE BLOGS [Blog # 37] Monday, September 22 @ 8:44 am PDT [Autumn Equinox] This blog that actually started at the end of May (see bottom of this blog) is finally finished and I’ll send it off to Sarah for site updating now at the start of Fall, astronomically speaking. Solstices & equinoxes are power points or intersections. One of the reasons I waited so long is because I wanted to wait for the release of Tribute’s The Kentuckian and also Tadlow’s El Cid. I received both from Screen Archives Entertainment on 9/11! So I wrote my reviews of both recordings, posted accordingly on Talking Herrmann and the Rozsa Forum, and I think that should do it. Here are the links: http://miklosrozsa.yuku.com/topic/912/t/EL-CID-Orchestrations.html http://herrmann.uib.no/talking/view.cgi?forum=thGeneral&topic=3052 http://www.screenarchives.com/title_detail.cfm?ID=10351 http://www.screenarchives.com/title_detail.cfm?ID=10068 That last link for the special edition El Cid set may already be out-of-print by the time this blog in the blogosphere because only a couple of hundred copies of the initial 3000 pressing are left (according to Sunday’s Rozsa Forum post by Tadlow). Tadlow will generate more but not in the slipcase. After that demand Tadlow will release a two- cd set (no special video third disc). In early January 2009 it will be the 10th anniversary of Film Score Rundowns. Matt Gear actually created it after seeing my small collection of rundown skeletal posts on Filmus-L. -

Hathaway Collection

Finding Aid for the Henry Hathaway Collection Collection Processed by: Yvette Casillas, 7.29.19 Finding Aid Written by: Yvette Casillas, 7.29.19 OVERVIEW OF THE COLLECTION: Origination/Creator: Hathaway, Henry Title of Collection: Henry Hathaway Collection Date of Collection: 1932 - 1970 Physical Description: 84 volumes, bound Identification: Special Collection #26 Repository: American Film Institute Louis B. Mayer Library, Los Angeles, CA RIGHTS AND RESTRICTIONS: Access Restrictions: Collection is open for research. Copyright: The copyright interest in this collection remain with the creator. For more information, contact the Louis B. Mayer Library. Acquisition Method: Donated by Henry Hathaway, circa 1975 . BIOGRAPHICAL/HISTORY NOTE: Henry Hathaway (1898 – 1985) was born Henri Leopold de Fiennes on March 13, 1889, in Sacramento, California, to actress Jean Weil and stage manager Henry Rhody. He started his career as a child film actor in 1911. In 1915 Hathaway quit school and went to work at Universal Studios as a laborer, later becoming a property man. He was recruited for service during World War I in 1917, Hathaway saw his time in the army as an opportunity to get an education. He was never deployed, contracting the flu during the 1918 influenza pandemic. After being discharged from the army in 1918, Hathaway pursued a career in financing but returned to Hollywood to work as a property man at Samuel Goldwyn Studios and Paramount Studios. By 1924 Hathaway was working as an Assistant Director at Paramount Studios, under directors such as Josef von Sternberg, Victor Fleming, Frank Lloyd, and William K. Howard. Hathaway Collection – 1 In 1932 Hathaway directed his first film HERITAGE OF THE DESERT, a western. -

Prospecting for Cultural Gold: the Western Mining Film, 1935-1960

Prospecting for Cultural Gold: The Western Mining Film, 1935-1960 By William Graebner SUNY-Fredonia f the thousands of westerns that Hol ible with the \Vestern's attention to the construc lywood has brought to the screen, per tion of an ideal, stable, family-based commu 0 haps a score take western gold or sil nity.' ver n1Jmng as their subject in some significant Although hardly Hollywood favorites, films way, and probably fewer than one hundred evoke about western mining are sufficiently numerous gold or silver mining or the mined metals in even to make possible some preliminary ideas about marginal or minimal ways. How to account for the history of the genre and its social and cul this dearth? Hollywood has seldom been at tural interpretive functions. It may even be pos tracted to the workplace, and the mining work sible to suggest a historical trajectory locating place is either dark-the mine shaft-or curi the apogee of the western mining ftlm in the la te ously amorphous-the stream bed. While the 1940s, when the genre's focus on a world tradi cry of "Eureka!" is likely to be good for the box tionally associated with men briefly coincided office, mining itself, whether by pick, sluice, or witl1 more general social and cultural imperatives. pan, is a prosaic, repetitive, and-for the film .My conclusions are based on a sample of viewer-rather boring activity. twelve films that were both relevant to the Indeed, about half of the "mining" films do query-some, admittedly, more than otl1ers-and not show any mining taking place. -

100 Rifles Worldwide 11 Harrowhouse Worldwide 12

100 Rifles Worldwide 11 Harrowhouse Worldwide 12 Rounds Worldwide 12 Rounds 2: Reloaded Worldwide 127 Hours Italy 20,000 Men a Year Worldwide 23 Paces to Baker Street Worldwide 27 Dresses Worldwide 28 Days Later Worldwide 3 Women Worldwide 45 Fathers Worldwide 500 Days of Summer Worldwide 9 to 5 Worldwide 99 and 44/100% Dead Worldwide A Bell For Adano Worldwide A Christmas Carol Worldwide A Cool Dry Place Worldwide A Cure for Wellness Worldwide A Farewell to Arms Worldwide A Girl in Every Port Worldwide A Good Day to Die Hard Worldwide A Guide for the Married Man Worldwide A Hatful of Rain Worldwide A High Wind in Jamaica Worldwide A Letter to Three Wives Worldwide A Man Called Peter Worldwide A Message to Garcia Worldwide A Perfect Couple Worldwide A Private's Affair Worldwide A Royal Scandal Worldwide A Tree Grows in Brooklyn Worldwide A Troll in Central Park Worldwide A Very Young Lady Worldwide A Walk in the Clouds Worldwide A Walk With Love and Death Worldwide A Wedding Worldwide A-Haunting We Will Go Worldwide Abraham Lincoln: Vampire Hunter Worldwide Absolutely Fabulous Worldwide Ace Eli and Rodger of the Skies Worldwide Adam Worldwide Advice to the Lovelorn Worldwide After Tomorrow Worldwide Airheads Worldwide Alex and the Gypsy Worldwide Alexander's Ragtime Band Worldwide Alien Worldwide Alien Resurrection Worldwide Alien Vs. Predator Worldwide Alien: Covenant Worldwide Alien3 Worldwide Aliens Worldwide Aliens in the Attic Worldwide Aliens Vs. Predator - Requiem Worldwide All About Eve Worldwide All About Steve Worldwide All That -

XX:4) Jules Dassin, NIGHT and the CITY (1950, 96 Min)

February 2, 2010 (XX:4) Jules Dassin, NIGHT AND THE CITY (1950, 96 min) Directed by Jules Dassin Screenplay by Jo Eisinger Based on the novel by Gerald Kersh Produced by Samuel G. Engel. Original Music by Benjamin Frankel (British version), Franz Waxman (American version) Cinematography by Mutz Greenbaum (director of photography, as Max Greene) Film Editing by Nick DeMaggio and Sidney Stone Constant Nymph (1933), Hindle Wakes (1931), Amours viennoises (1931), Die Försterchristl (1931), Zwei Menschen (1930), Zwei Richard Widmark...Harry Fabian Welten (1930, Der Präsident (1928), Frauenraub in Marokko Gene Tierney...Mary Bristol (1928), Das goldene Kalb (1925), Das tanzende Herz (1916), and Googie Withers...Helen Nosseross Hampels Abenteuer (1915). Hugh Marlowe...Adam Dunn Francis L. Sullivan...Philip Nosseross RICHARD WIDMARK (December 26, 1914, Sunrise Township, Herbert Lom...Kristo Minnesota—March 24, 2008, Roxbury, Connecticut, from Stanislaus Zbyszko...Gregorius complications following a fall) appeared in 75 films and tv series, Mike Mazurki...The Strangler some of which were True Colors (1991), Against All Odds (1984), Charles Farrell...Mickey Beer National Lampoon's Movie Madness (1982) The Swarm (1978), Ada Reeve...Molly the Flower Lady Twilight's Last Gleaming (1977), Murder on the Orient Express Ken Richmond...Nikolas of Athens (1974), "Madigan" (6 episodes, 1972-1973), Death of a Gunfighter (1969), Madigan (1968), Alvarez Kelly (1966), The Bedford JULES DASSIN (18 December 1911, Middletown, Connecticut, Incident (1965), Cheyenne Autumn (1964), How the West Was Won USA—31 March 2008, Athens, Greece, complications from flu) (1962), Judgment at Nuremberg (1961), Two Rode Together (1961), directed 25 films, including Circle of Two/Obsession (1980), The The Alamo (1960), Warlock (1959), The Law and Jake Wade Rehearsal (1974), Promise at Dawn (1970), 10:30 P.M. -

New on Video &

New On Video & DVD Two and a Half Men Season 3 Charlie Sheen takes a starring role in Two And A Half Men, a genial CBS comedy about a dysfunctional family. Sheen plays Charlie Harper, who enjoys the bachelor life in his Malibu beach house. His existence consists of an endless stream of partying and dating until his brother, Alan (Jon Cryer), moves in with him. Alan's life has fallen apart after a separation from his wife, but he still has custody of his young son, Jake (Angus T. Jones), who also moves into Charlie's Malibu home. Supporting characters include Alan's crazy ex-wife, Charlie and Alan's overbearing mother, and their sharp-tongued housekeeper Berta. The makeshift family formed by Charlie, Alan, and Jake provides plenty of laughs and a few poignant moments in this complete third season of episodes. Warner Fox Western Classics: Rawhide, The Gunfighter & Garden of Evil. One of the first of the '50s "adult Westerns," "The Gunfighter" (1950) stars Gregory Peck as a weary gunslinger trying to visit his estranged wife and son, but finding from town to town that he can't escape his reputation as "fastest draw in the land." With Karl Malden, Helen Westcott, Millard Mitchell. Next, the 1935 gangster film "Show Them No Mercy" was transformed into a Western for "Rawhide" (1951), a suspenseful tale of four people at a stagecoach station who are taken hostage by a gang of robbers. Tyrone Power, Susan Hayward, Hugh Marlowe, Dean Jagger, and Edgar Buchanan star. And, three men on their way to mine for gold in California stop in Mexico where they accept a lucrative--and dangerous--offer from a woman who promises them $2,000 each to rescue her husband from a caved-in mine shaft, in "Garden of Evil" (1954). -

Large Print Books in the Menlo Park Library Sorted by Author's Name List

Large print books in the Menlo Park Library sorted by author’s name List run 12/03/11 Story collections or edited works: Funny letters from famous people Christmas stalkings Murder in Manhattan Mystery cats Travels in America Alfred Hitchcock's tales to send chills down your spine Every woman has a story The Californians Famous detective stories in large print The New Merriam-Webster dictionary for large print users The best British mysteries. What ifs? of American history The best British mysteries. New trails Favorite short stories in large print Favorite short stories in large print Holy Bible Great stories of the American West Alfred Hitchcock's Tales to make your blood run cold, anthology 1 Gilgamesh Three weddings and a kiss Rodale's garden answers Primary colors Westeryear Chicken soup for the soul The Holy Bible English country house murders The Dick Francis treasury of great racing stories Understanding arthritis Naked came the manatee War in the air The games we played Naked came the phoenix Out of this world Light on aging and dying I thought my father was God, and other true tales from NPR's National Story Project Merriam-Webster's concise dictionary My America The Random House Large Print treasury of best-loved poems The Official Scrabble players dictionary The Right words at the right time A Regency valentine, volume II The Holy Bible : Live strong The people's princess Comfort and joy Dear Mrs. Kennedy The longevity project Abbott, Jeff. Cut and run Abbott, Jeff. Panic Abel, Kenneth. The blue wall Abel, Kenneth. -

Janfeb Adult NL 2004

Jan / Feb 2004 Vol. 5 / Issue 1 Author Carol Cail visited the Eaton Library New in Self-Help While visiting family and friends in her old Naomi’s Breakthrough Guide : home-town, mystery author Carol Cail took time 20 choices to transform your out from her busy schedule to participate in a life / Naomi Judd: How did a book discussion at the Eaton Library. Over woman who missed her high school twenty guests were in attendance, a very nice graduation to deliver her first child, who turn-out! endured domestic abuse, lived on wel- fare, and overcame a life-threatening During her presentation Carol discussed: illness, find the inner strength to perse- vere? As Naomi puts it, "a dead end is Her writing career -- especially the fact that just a good place to turn around." Now most writers do not make a fortune at the in Naomi's Breakthrough Guide she craft as do writers like Stephen King and shares with readers the hard-won wis- Mary Higgins Clark. dom that helped her turn potential breakdowns into life- How she was lucky enough (and talented, altering breakthroughs. might I add!) to sell her very first book Awareness and responsibility are the foundations of Naomi's which was a romance novel approach to personal transformation. As she'll tell you, Her childhood memories of Eaton change is the true nature of the universe, but it is how we choose to respond to change that determines whether or not How it took her many years to get her new- we lead healthy, happy lives. -

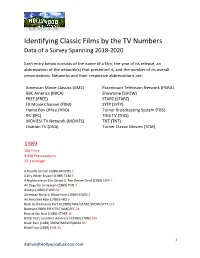

Identifying Classic Films by the TV Numbers Data of a Survey Spanning 2018-2020

Identifying Classic Films by the TV Numbers Data of a Survey Spanning 2018-2020 Each entry below consists of the name of a film, the year of its release, an abbreviation of the network(s) that presented it, and the number of its overall presentations. Networks and their respective abbreviations are: American Movie Classics (AMC) Paramount Television Network (PARA) BBC America (BBCA) Showtime (SHOW) FREE (FREE) STARZ (STARZ) FX Movie Channel (FXM) SYFY (SYFY) Home Box Office (HBO) Turner Broadcasting System (TBS) IFC (IFC) THIS TV (THIS) MOVIES! TV Network (MOVIES) TNT (TNT) Ovation TV (OVA) Turner Classic Movies (TCM) 1989 150 Films 4,958 Presentations 33,1 Average A Deadly Silence (1989) MOVIES 1 A Dry White Season (1989) TCM 4 A Nightmare on Elm Street 5: The Dream Child (1989) SYFY 7 All Dogs Go to Heaven (1989) THIS 7 Always (1989) STARZ 69 American Ninja 3: Blood Hunt (1989) STARZ 2 An Innocent Man (1989) HBO 5 Back to the Future Part II (1989) MAX/STARZ/SHOW/SYFY 272 Batman (1989) SYFY/TNT/AMC/IFC 24 Best of the Best (1989) STARZ 16 Bill & Ted’s Excellent Adventure (1989) STARZ 140 Black Rain (1989) SHOW/MOVIES/MAX 85 Blind Fury (1989) THIS 15 1 [email protected] Born on the Fourth of July (1989) MAX/BBCA/OVA/STARZ/HBO 201 Breaking In (1989) THIS 5 Brewster’s Millions (1989) STARZ 2 Bridge to Silence (1989) THIS 9 Cabin Fever (1989) MAX 2 Casualties of War (1989) SHOW 3 Chances Are (1989) MOVIES 9 Chattahoochi (1989) THIS 9 Cheetah (1989) TCM 1 Cinema Paradise (1989) MAX 3 Coal Miner’s Daughter (1989) STARZ 1 Collision -

American Film Actor and Icon 1901—1961

American Film Actor and Icon 1901—1961 When Cooper played a cowboy you really believed he was a cowboy, and when he played an international man of sophistication, he was just as believable. That had a real effect on me, and we what I found so interesting about him. He was at home in either role and always convincingly authentic. There weren’t many actors that could do that, which is why Gary Cooper was not only the biggest star of his time, but also the definitive “American” move star—handsome, honorable, honest. -Ralph Lauren The Westerner (1940) Morocco (1930) Gary Cooper was born Frank James Cooper in Helena, Montana, one of two sons of an English farmer from Bedfordshire, who later became an American lawyer and judge, Charles Henry Cooper (1865-1946), and Kent-born Alice (née Brazier) Cooper (1873-1967). His mother hoped for their two sons to receive a better education than that available in Montana and arranged for the boys to attend Dunstable Grammar School in Bedfordshire, England between 1910 and 1913.Upon the outbreak of World War I, Cooper's mother brought her sons home and enrolled them in a Bozeman, Montana, high school. When Cooper was 13, he injured his hip in a car accident. He returned to his parents' ranch near Helena to recuperate by horseback riding at the recommendation of his doctor. Cooper studied at Iowa's Grinnell College until the spring of 1924, but did not graduate. He had tried out, unsuccessfully, for the college's drama club. He returned to Helena, managing the ranch and contributing cartoons to the local newspaper.