GAO-16-115T, SCREENING PARTNERSHIP PROGRAM: Subtitle

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

May 7,2009 Be Available in the Near Future at Http

Monlo no De porlme nf of lronsoo rt oii on Jim Lvnch, Dîrector *ruhrylaùtlthNde 2701 Prospect Avenue Brîon Schweífzer, Gov ernor PO Box 201001 Heleno MT 59620-1001 May 7,2009 Ted Mathis Gallatin Field 850 Gallatin Field Road #6 Belgrade MT 59714 Subject: Montana Aimorts Economic knpact Study 2009 Montana State Aviation System Plan Dear Ted, I am pleased to announce that the Economic Impact Study of Montana Airports has been completed. This study was a two-year collaborative eflort between the Montana Department of Transportation (MDT) Aeronautics Division, the Federal Aviation Administration, Wilbur Smith and Associates and Morrison Maierle Inc. The enclosed study is an effort to break down aviation's significant contributions in Montana and show how these impacts affect economies on a statewide and local level. Depending on your location, you may also find enclosed several copies of an individual economic summary specific to your airport. Results ofthe study clearly show that Montana's 120 public use airports are a major catalyst to our economy. Montana enplanes over 1.5 million prissengers per year at our 15 commercial service airports, half of whom are visiting tourists. The economic value of aviation is over $1.56 billion and contributes nearly 4.5 percent to our total gross state product. There arc 18,759 aviation dependent positions in Montana, accounting for four percent of the total workforce and $600 million in wages. In addition to the economic benefits, the study also highlights how Montana residents increasingly depend on aviation to support their healtþ welfare, and safety. Montana airports support critical services for medical care, agriculture, recreation, emergency access, law enforcement, and fire fighting. -

Federal Register / Vol. 62, No. 119 / Friday, June 20, 1997 / Notices 33697

Federal Register / Vol. 62, No. 119 / Friday, June 20, 1997 / Notices 33697 DEPARTMENT OF TRANSPORTATION statements at the meeting. The public Brief Description of Projects Approved may present written statements to the for Use: Air carrier apron rehabilitation, Federal Aviation Administration committee at any time by providing 12 Runway 15/33 rehabilitation. copies to the person listed under the Decision Date: May 2, 1997. Weather Enhancement Advisory heading FOR FURTHER INFORMATION For Further Information Contact: Subgroup Meeting on Alaska Aviation CONTACT: or by bringing the copies to David P. Gabbert, Helena Airports Weather Requirements the meeting. District Office, (406) 449±5271. AGENCY: Federal Aviation Issued in Washington, DC, June 16, 1997. Public Agency: City of Oklahoma City, Administration (FAA), DOT. William H. Brodie, Jr., Department of Airports, Oklahoma City, ACTION: Notice of meeting. Special Assistant to Program Director, Oklahoma. Aviation Weather Directorate, ARW±1. Application Number: 97±01±C±00± SUMMARY: The Federal Aviation [FR Doc. 97±16186 Filed 6±19±97; 8:45 am] OKC. Administration (FAA) is issuing this Application Type: Impose and use a BILLING CODE 4910±13±M notice to advise the public of a meeting PFC. of the FAA Weather Enhancement PFC Level: $3.00. Advisory Subgroup to discuss Alaska DEPARTMENT OF TRANSPORTATION Total Net PFC Revenue Approved in Aviation Weather Requirements. This Decision: $10,446,875. DATES: The meeting will be held July 14, Federal Aviation Administration Earliest Charge Effective Date: July 1, 1997, from 1:00 p.m. to 4:00 p.m. 1997. Arrange for presentations by July 3, Notice of Passenger Facility Charge Estimated Charge Expiration Date: 1997. -

TSA -Screening Partnership Program FY 2015 1St Half

Screening Partnership Program First Half, Fiscal Year 2015 June 19, 2015 Fiscal Year 2015 Report to Congress Transportation Security Administration Message from the Acting Administrator June 19, 2015 I am pleased to present the following report, “Screening Partnership Program,” for the first half of Fiscal Year (FY) 2015, prepared by the Transportation Security Administration (TSA). TSA is submitting this report pursuant to language in the Joint Explanatory Statement accompanying the FY 2015 Department of Homeland Security Appropriations Act (P.L. 114-4). The report discusses TSA’s execution of the Screening Partnership Program (SPP) and the processing of SPP applications. Pursuant to congressional requirements, this report is being provided to the following Members of Congress: The Honorable John R. Carter Chairman, House Appropriations Subcommittee on Homeland Security The Honorable Lucille Roybal-Allard Ranking Member, House Appropriations Subcommittee on Homeland Security The Honorable John Hoeven Chairman, Senate Appropriations Subcommittee on Homeland Security The Honorable Jeanne Shaheen Ranking Member, Senate Appropriations Subcommittee on Homeland Security Inquiries relating to this report may be directed to me at (571) 227-2801 or to the Department’s Chief Financial Officer, Chip Fulghum, at (202) 447-5751. Sincerely yours, Francis X. Taylor Acting Administrator i Screening Partnership Program First Half, Fiscal Year 2015 Table of Contents I. Legislative Language ......................................................................................................... -

Federal Register / Vol. 60, No. 75 / Wednesday, April 19

Federal Register / Vol. 60, No. 75 / Wednesday, April 19, 1995 / Notices 19619 membership, the new entity will be FOR FURTHER INFORMATION CONTACT: Dated: April 7, 1995. subject to all other requirements for June Gibbs Brown, membership approval. Olive Franklin, Office of Investigations, Inspector General. (202)±619±2501.Glenn Sklar, Office of The Commission believes that the [FR Doc. 95±9579 Filed 4±18±95; 8:45 am] the General Counsel, (410)±965±6247. amendments to Articles V and VIII of BILLING CODE 4190±29±±M the PSE Constitution reasonably balance SUPPLEMENTARY INFORMATION: The Social the Exchange's interest in having the Security Independence and Program flexibility to approve entities with new Improvements Act of 1994 (SSIPIA), DEPARTMENT OF TRANSPORTATION organizational structures for Exchange Pub. L. 103±296, separated the Social membership, with the regulatory Security Administration (SSA) from its Office of the Secretary interests in protecting the financial and parent agency, the Department of Health [Order 95±4±20] structural integrity of a member and Human Services (HHS), and organization. For example, although the established SSA as an independent Reissuance of the Section 41102 amendments permit the Exchange to agency effective March 31, 1995. The Certificate to Village Aviation, Inc.; approve business trusts, limited liability SSIPIA also required that all functions d/b/a Camai Air; Order to Show Cause companies, or other organizational relating to SSA that were previously structures with characteristics of performed by the HHS/IG must be AGENCY: Department of Transportation. corporations or partnerships as member transferred to the SSA/IG. In order to ACTION: Notice of reissuance of section organizations, the PSE will review each perform these functions, the SSA/IG 41102 certificate. -

Federal Register / Vol. 60, No. 75

19620 Federal Register / Vol. 60, No. 75 / Wednesday, April 19, 1995 / Notices petitions seeking relief from specified response medical helicopter; medically FOR FURTHER INFORMATION CONTACT: requirements of the Federal Aviation necessary relocation of patients to Mr. David P. Gabbert, (406) 449±5271; Regulations (14 CFR Chapter I), specialized care facilities; emergency Helena Airports District Office, HLN± dispositions of certain petitions search and rescue operations, over lake ADO; Federal Aviation Administration; previously received, and corrections. areas and isolated terrain; law FAA Building, Suite 2; 2725 Skyway The purpose of this notice is to improve enforcement support, when requested Drive; Helena, Montana 59601. The the public's awareness of, and by county, city, or state agencies; fire application may be reviewed in person participation in, this aspect of FAA's suppression bucket operations and at this same location. regulatory activities. Neither publication external load support during fire of this notice nor the inclusion or fighting assignments throughout the SUPPLEMENTARY INFORMATION: The FAA omission of information in the summary county and the immediate surrounding proposes to rule and invites public is intended to affect the legal status of counties; general government air comment on the application to use PFC any petition or its final disposition. operations, such as search and rescue in revenue at Bert Mooney Airport, under the provisions of 49 U.S.C. 40117 and DATE: Comments on petitions received flood operations, biological research, Part 158 of the Federal Aviation must identify the petition docket and litigation support when an aerial Regulations (14 CFR Part 158). number involved and must be received view is necessary for the operation to be On April 13, 1995, the FAA on or before May 1, 1995. -

Bert Mooney Airport – BUTTE Bert Mooney Airport BUTTE Qualitative Benefits

BERT MOONEY AIRPORt – BUTTE BERT MOONEY AIRPORT BUTTE QUALITATIVE BENEFITS In addition to the economic benefits described above, Bert Mooney Airport provides access and services that promote the well being of the local community. Aviation activities that take place on a regular basis in addition to commercial airline service include recreational flying, corporate aviation, air cargo operations by UPS and FedEx, civilian and military flight training, visitor access to local resorts, career training and education, prisoner transport, medi- cal shipments and patient transfer, seasonal forest and rangeland firefighting operations, and search and rescue operations. On a weekend in July 2008, volunteers from across the state gathered in Butte for a search and rescue and disaster relief exercise. The Montana Wing of the Civil Air Patrol (CAP) conducted an exercise to demonstrate the organization’s capabilities in search and rescue, disaster relief and homeland security operations. St. James Healthcare in Butte, Montana also uses the airport frequently. A survey of 35 hospitals in Montana gathered data to obtain informa- tion relating to how often hospitals use airports in Montana to bring in specialists from out of the area, as well as how often airports are used for patient transfer. Survey data indicated St. James Healthcare uses Bert Mooney Airport on average 72 times per year to bring doctors and specialists to the hospital to conduct clinics. These doctors fly in from Las Vegas and Salt Lake City. The hospital also uses the airport 36 times per year on average for emergency patient transfer via air ambulance. Bert Mooney Airport also benefits the local community by sponsoring an annual business card social, an event that draws 200 to 300 attendees each year. -

Strata Energy Inc.), 2016, Ross ISR Project Annual Surety Estimate, Revised March 2016, March 11, 2016

Application for Amendment of USNRC Source Materials License SUA-1601, Ross ISR Project, for the Kendrick Expansion Area RAI Question and Answer Responses for the Kendrick Expansion Area Environmental Report Docket #40-09091 Prepared for: U.S. Nuclear Regulatory Commission 11545 Rockville Pike Rockville, MD 20852 Prepared by: Strata Energy, Inc. 1900 W. Warlow Drive, Bldg. A P.O. Box 2318 Gillette, WY 82717-2318 August 2016 TABLE OF CONTENTS General ............................................................................................................... 1 ER RAI GEN-1(A) Response ...................................................................................... 1 ER RAI GEN-1(B) and (C) Response .......................................................................... 3 ER RAI GEN-2(A) Response .................................................................................... 15 ER RAI GEN-2(B) Response .................................................................................... 16 ER RAI GEN-2(C) Response .................................................................................... 17 ER RAI GEN-2(D) Response .................................................................................... 18 ER RAI GEN-3 Response ......................................................................................... 20 ER RAI GEN-4 Response ......................................................................................... 22 ER RAI GEN-5 Response ........................................................................................ -

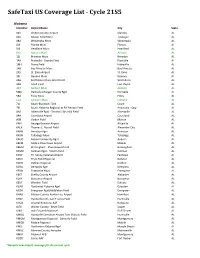

Safetaxi US Coverage List - Cycle 21S5

SafeTaxi US Coverage List - Cycle 21S5 Alabama Identifier Airport Name City State 02A Chilton County Airport Clanton AL 06A Moton Field Muni Tuskegee AL 08A Wetumpka Muni Wetumpka AL 0J4 Florala Muni Florala AL 0J6 Headland Muni Headland AL 0R1 Atmore Muni Atmore AL 12J Brewton Muni Brewton AL 1A9 Prattville - Grouby Field Prattville AL 1M4 Posey Field Haleyville AL 1R8 Bay Minette Muni Bay Minette AL 2R5 St. Elmo Airport St. Elmo AL 33J Geneva Muni Geneva AL 4A6 Scottsboro Muni-Word Field Scottsboro AL 4A9 Isbell Field Fort Payne AL 4R3 Jackson Muni Jackson AL 5M0 Hartselle-Morgan County Rgnl Hartselle AL 5R4 Foley Muni Foley AL 61A Camden Muni Camden AL 71J Ozark-Blackwell Field Ozark AL 79J South Alabama Regional at Bill Benton Field Andalusia - Opp AL 8A0 Albertville Rgnl - Thomas J Brumlik Field Albertville AL 9A4 Courtland Airport Courtland AL A08 Vaiden Field Marion AL KAIV George Downer Airport Aliceville AL KALX Thomas C. Russell Field Alexander City AL KANB Anniston Rgnl Anniston AL KASN Talladega Muni Talladega AL KAUO Auburn University Rgnl Auburn AL KBFM Mobile Downtown Airport Mobile AL KBHM Birmingham - Shuttlesworth Intl Birmingham AL KCMD Cullman Rgnl - Folsom Field Cullman AL KCQF H L Sonny Callahan Airport Fairhope AL KDCU Pryor Field Regional Decatur AL KDHN Dothan Regional Dothan AL KDYA Dempolis Rgnl Dempolis AL KEDN Enterprise Muni Enterprise AL KEET Shelby County Airport Alabaster AL KEKY Bessemer Airport Bessemer AL KEUF Weedon Field Eufaula AL KGAD Northeast Alabama Rgnl Gadsden AL KGZH Evergreen Rgnl/Middleton -

1 of 4 REGULAR MEETING of THE

REGULAR MEETING OF THE MONTEREY PENINSULA AIRPORT DISTRICT BOARD OF DIRECTORS July 8, 2015 10:00 AM Board Room, 2nd Floor of the Airport Terminal Building 200 Fred Kane Dr. Suite #200 Monterey Regional Airport (Unless you are a public safety official, please turn off your cell phone or place it on vibrate mode during the meeting. Thank you for your compliance.) A. CALL TO ORDER/ROLL CALL B. PLEDGE OF ALLEGIANCE C. COMMUNICATIONS/ANNOUNCEMENTS/INFORMATIONAL ITEMS 1. Introduction of New Employee Name Department Position Brandon Segovia Public Safety Police Officer 2. Police Chief Award Presentation 3. Report to Board by Director Miller: AAAE Conference, Philadelphia D. PUBLIC COMMENTS Any person may address the Monterey Peninsula Airport District Board at this time. Presentations should not exceed three (3) minutes, should be directed to an item NOT on today’s agenda, and should be within the jurisdiction of the Monterey Peninsula Airport District Board. Though not required, the Monterey Peninsula Airport District Board appreciates your cooperation in completing a speaker request form available on the staff table. Please give the completed form to the Monterey Peninsula Airport District Secretary. Comments concerning matters set forth on this agenda will be heard at the time the matter is considered.) E. CONSENT AGENDA – ACTION ITEMS (10:15AM – 10:20AM Estimated) (The Consent Agenda consists of those items which are routine and for which a staff recommendation has been prepared. A Board member, member of the audience or staff may request that an item be placed on the deferred consent agenda for further discussion. One motion will cover all items on the Consent Agenda. -

July 2009 Jobs Report

SUMMARY Contract Contracts Contracts Contracts Amount Awarded (less Amount of ARRA Funds Contract Solicitations Contracts Completed Direct Jobs (Job Award Recipient Amount of ARRA Funds Committed Solicitations Awarded Contracts Awarded (Amount) Underway Contracts Underway (Amount) completed State-Source Funding (Planned) State-Source Funding (Actual) transfers) Outlayed or Expended (Amount) (Amount) Months) (Number) (Number) (Number) (Number) FAA - Grants-in-aid for Airports $910,562,818 $910,562,818 $108,760,358 575 $780,391,645 567 $760,237,324 548 $708,337,917 43 $91,917,544 3,067.49 $0 $0 FRA - Capital Grants to the National Railroad Passenger Corporation $1,293,252,000 $153,961,698 $10,822,724 128 $608,481,698 95 $60,161,698 95 $60,161,698 0 $0 357.02 $0 $0 FTA - Capital Investment Grants $233,630,000 $233,630,000 $172,300,266 141 $227,756,832 141 $227,756,832 141 $227,756,832 91 $151,756,832 10,851.33 $0 $0 FTA - Fixed Guideway Infrastructure Investment $423,508,950 $197,574,790 $58,287,225 134 $125,531,129 102 $92,414,603 97 $79,816,936 50 $3,549,370 5,918.60 $1,387,736,554 $400,923,004 FTA - Transit Capital Assistance $3,530,133,610 $1,745,031,609 $344,216,722 2036 $2,121,564,776 1600 $1,442,266,456 1396 $1,130,108,059 650 $117,863,434 32,204.79 $379,420,005 $96,703,489 FHWA - Highway Infrastructure Investment $26,768,512,663 $17,328,396,270 $681,240,337 2960 $9,733,575,261 2893 $9,494,566,816 2481 $7,840,351,685 213 $260,975,755 30,391 $27,966,338,116 $10,016,668,919 GRAND TOTAL $33,159,600,041 $20,569,157,185 $1,375,627,632 -

Montana Airports 2016 Economic Impact Study

MONTANA AIRPORTS Y D TU T S AC MP 2016 C I OMI ECON Introduction Montana’s airports play an integral role in our transportation system by providing access to destinations within the state, throughout the country, and across the globe. Airports also offer significant economic benefits to our communities by supporting jobs; generating payroll; paying taxes; and triggering spending at local, regional, and state levels. The importance of airports goes beyond transportation and economics. Airports offer access, services, and other valuable attributes for Montanans that cannot always be easily measured in dollars and cents. Residents and visitors use airports for leisure and business travel, and airports serve as the base for a wide range of critical activities such as wildland firefighting, search and rescue operations, and training for future aviators. Airports are the starting point for aircraft that conduct utility inspections, provide medical evacuation services, and transport staff and executives for business activity. This Economic Impact Study analyzed the contributions of Montana’s airports to determine the benefits that airports provide throughout the state. This study updated the previous analysis conducted in 2007 and 2008. CLASSIFICATION OF AIRPORTS Commercial General Aviation Service Airports Airports MONTANA 1 AIRPORTS 2016 Economic Impact Study Methodology To better understand the value of Montana’s airports from the perspective of both economics and community benefits, the Montana Department of Transportation (MDT) conducted a comprehensive study of the state’s aviation facilities. The study analyzed the contributions of Montana’s airports, including aviation- and non-aviation-related businesses, visitor spending, capital expenditures on construction, and additional spin-off (or “multiplier”) effects. -

Airport L&G Board Meeting Minutes

January 16, 2020 Montana Aeronautics Board Montana Department of Transportation; Auditorium 2701 Prospect Avenue, Helena, MT Thursday, January 16, 2020 Aeronautics Board Department of Transportation Tricia McKenna, Board Chairperson Mike Tooley, MDT Director Walt McNutt, Vice-Chairperson Tim Conway, MDT Aeronautics Roger Lincoln, Secretary Wade Cebulski, MDT Aeronautics Robert Buckles Karen Speeg, MDT Aeronautics Dan Hargrove Effie Benoit, MDT Aeronautics Bill Hunt, Jr Carol Grell-Morris, MDT Legal John Maxness Valerie Balukas, MDT Legal Tom Schoenleben Jeff Wadekamper Guests Bryon Armour, Lewistown Airport Lucas Locke, Valley County Greg Bahr, Anaconda Airport Manager Doug McClarion, Ravalli County Airport Keith Belden, Morrison Maierle Steve Mosby, Lewistown Airport Mary Bell, Robert Peccia & Associates Kevin Myhre, Century Co, Inc. Kristie Brabeck, Valley County Rick Newman, Lake County Joint Airports Lance Bowser, Robert Peccia & Associates Mark Peterson, Havre Airport Board Craig Canfield, KLJ Doug Phair, Miles City Airport Pam Chamberlin, Bert Mooney Airport Tyler Reed, Morrison Mairele Katie Coleman-Assad, Stevensville Airport Rick Ryan, Bert Mooney Airport Nigel Davis, Morrison Maierle Nathan Schroht, KLJ Chris Dodge, Jacobs Engineering Adam Share, Morrison Mairele Rick Donaldson, Robert Peccia & Associates Pete Smith, Lewistown Airport Scott Eaton, Federal Aviation Administration Chase Stoner, Havre Airport Travis Eickman, Morrison Maierle Eric Strong, DOWL Andy Galen, Morrison Maierle Craig Thomas, Town of Stevensville Jim Greil, DOWL Robert Underwood, Town of Stevensville Bret Hascamp, Ravalli County Airport Clint Von Voast, Blaine County David Hedditch, Hamilton, MT Dempsey Vick, Town of Stevensville Jack Hinman, Choteau Airport Forrest Walker, Robert Peccia & Associates Cory Kesler, Morrison Maierle Dave Whitehair, Town of Stevensville Call to Order • Chairperson McKenna called the meeting to order at 8:00 a.m.