Management and Outcome of Ruptured Hepatocellular Carcinoma

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Introduction

Introduction This report, Situation of the Thai Elderly 2019, is a production of the National Commission on Older Persons which has the responsibility to issue this report in accordance with Article 9(10) of the Elderly Act of 2003, and present the findings to the Cabinet each year. Ever since 2006, the National Commission on Older Persons has assigned the Foundation of Thai Gerontology Research and Development Institute (TGRI) to implement this assignment. This edition compiles data and information on older Thai persons for the year 2019, and explores trends in changes of the age structure of the population in the past in order to project the situation of older persons in the future. Each edition of the annual report on the Situation of the Thai Elderly has a particular focus or theme. For example, the 2013 edition focused on income security of older persons, the 2014 issue emphasized the vulnerability of older persons in the event of natural disasters, the 2015 focused on living arrangements of older persons, the 2016 edition focused on the health of the Thai elderly, the 2017 edition explored the concept of active aging in the Thai context of older persons, while the 2018 edition examined Thai elderly and employment. For the current edition (2019), the focus is on the social welfare of the elderly. In one sense, ‘Social Welfare’ sounds like a distant dream or ideal for Thai society, especially given the threat of the country’s being caught in the “middle-income trap.” However, if one considers examples of past policy, whether it is education or public health, Thailand should be able to create a system that covers the priority target groups, reduces the burden, and creates opportunities for people to have a good quality of life. -

The Study of Gingerbread Houses in Thailand Case Study: Bangkok, Vicinity and Phrae

The Study of Gingerbread Houses in Thailand Case Study: Bangkok, Vicinity and Phrae First Author Asst. Prof. Patravadee Siriwan Faculty of Engineering and Architecture, Rajamangala University of Technology Suvarnabhumi, Nonthaburi Campus E-mail Address: [email protected] Co-Author Asst. Prof. Dr. Rungpassorn Sattahanapat Faculty of Liberal Arts, Rajamangala University of Technology Suvarnabhumi, Nonthaburi Campus E-mail Address: [email protected] ABSTRACT: This research aims to study the architectural patterns of the Gingerbread houses and the decorations of the Gingerbread houses in Thailand. Case Study: Bangkok and Its Vicinities and Phrae Province. The research starts with 1.) the study of the details received from related researches 2.) the study of the concepts received from related documents 3.) the creation of the questionnaire 4.) the survey of the actual locations 5.) the interviews with the officials, the houses’ owners and the house attendants 6.) the syntheses and the analyses of the data 7.) the conclusion and the discussion. The Gingerbread houses to be studies this time include… 1. Vimanmek Mansion, Bangkok 2. Abhisek Dusit Throne Hall, Bangkok 3. Gingerbread Monks’ Cells in Suan Plu Temple, Bangkok 4. Golden Teak Museum, Thewarat Kunchorn Worawiharn Temple, Bangkok 5. Diamond Palace, Bovorn Niwet Wihan Temple, Bangkok 6. Ban Ekanak Museum, Bangkok 7. Ruean Phra Thanesuan, Sanam Chan Palace, Nakhon Pathom Province 8. Baan Wong Buri, Phrae Province 9. Khum Chao Luang, Phrae Province. The research result shows that ginger-bread-house architecture in Thailand is mostly designed by wood-twisted pattern. The pattern is soft, pleasant and tiny called “Ginger-Bread Pattern”. This pattern is used for decorating houses for both one- storey and two-storey buildings. -

The Prevalence of Cognitive Frailty and Pre-Frailty Among Older People in Bangkok Metropolitan Area: a Multicenter Study of Hospital-Based Outpatient Clinics

Journal of Frailty, Sarcopenia and Falls Original Article The prevalence of cognitive frailty and pre-frailty among older people in Bangkok metropolitan area: a multicenter study of hospital-based outpatient clinics Panuwat Wongtrakulruang1, Weerasak Muangpaisan2, Bubpha Panpradup3, Aree Tawatwattananun4, Monchai Siribamrungwong5, Sasinapha Tomongkon6 1Department of Medicine, Faculty of Medicine Siriraj Hospital, Mahidol University, Bangkok, Thailand; 2Department of Preventive and Social Medicine, Faculty of Medicine Siriraj Hospital, Mahidol University, Bangkok, Thailand; 3Department of Nursing, Lerdsin Hospital, Bangkok, Thailand; 4Department of Nursing, Krathum Baen Hospital, Samut Sakhon, Thailand; 5Department of Internal Medicine, Lerdsin Hospital, Bangkok, Thailand; 6Department of Internal Medicine, Krathum Baen Hospital, Samut Sakhon, Thailand Abstract Objectives: To identify the prevalence of, and factors associated with, cognitive frailty and prefrailty, and to investigate correlation between frailty tools. Methods: One hundred and ninety five older adults were recruited from the medical outpatient clinics of 3 tertiary hospitals in Bangkok metropolitan region. The data collected were demographic information, lifestyle factors, functional status, mood assessment, and cognitive and frailty assessments. The frailty tools used were Frailty Phenotype and FRAIL scale. Results: The prevalence of pre-frailty, frailty, mild cognitive impairment (MCI), cognitive pre-frailty and cognitive frailty was 57.4%, 15.9%, 26.2%, 14.4% and 6.7%, respectively. A multivariate analysis showed that age ≥70 years (OR 5.34; 95% CI 2.06- 12.63), and education at primary school or under (OR 4.18; 95% CI 1.61-10.82) were associated with cognitive frailty and cognitive pre-frailty. The correlation between physical frailty rated by the Modified Fried Frailty Phenotype and the FRAIL scale was good (Kappa coefficient = 0.741). -

Annual Report 2016 Eng(Final)

ANNUAL REPORT 2016 131 Vision Business Objective Vichaivej International Hospital Group is strongly determined Vichaivej International Hospital Group’s operation focuses to be the leading hospital that operates at international standard on providing superb quality services for patients and others level by using modern technologyand medical equipment, engaging who visit the hospital and on engaging specialized medical teams of specialistphysicians from every field, and upholding treatment combined with preventive measures under the strict moraland ethical principles. slogan “V care V cure V can”. Our objectives are as follows. 1. Develop the hospital group to become one of the leading private hospital groups that is equipped with treatment capability in every field of medicine, with emphasis on accident and Orthopedic care. The objective is to become a Mission medical center for specific disease and eventually escalating into Tertiary Medical Care, involving development of necessary “We are firmly determined to provide medical care service medical personnel and modern diagnostic and treatment that is based on holistic professional standards through use of facilities ready to administer complicated diseases. quality tools and qualified staffs and by adopting a service 2. Set high standards for quality and service and focus recipient-centric approach in order to be sure that our service on being customer-centric with a genuine belief that recipients receive utmost satisfaction.” “customers are highly valued individuals which every hos- pital personnel has to pay close attention and ensure that they receive proper medical treatment, health care, and various services available at the hospital in a proper manner and according to professional standards, which in all creates utmost satisfied experience for the customers.” 3. -

Conservation of Heritage Healthcare Architecture; a Case Study at Siriraj Hospital, Bangkok Thailand

CONSERVATION OF HERITAGE HEALTHCARE ARCHITECTURE; A CASE STUDY AT SIRIRAJ HOSPITAL, BANGKOK THAILAND By Nantawat Sitdhiraksa A Thesis Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY Program of Architectural Heritage Management and Tourism (International Program) Graduate School SILPAKORN UNIVERSITY 2011 CONSERVATION OF HERITAGE HEALTHCARE ARCHITECTURE; A CASE STUDY AT SIRIRAJ HOSPITAL, BANGKOK THAILAND By Nantawat Sitdhiraksa A Thesis Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY Program of Architectural Heritage Management and Tourism (International Program) Graduate School SILPAKORN UNIVERSITY 2011 The Graduate School, Silpakorn University has approved and accredited the Thesis title of “Conservation of Heritage Healthcare Architecture; A Case Study at Siriraj Hospital, Bangkok Thailand” submitted by Mr.Nantawat Sitdhiraksa as a partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Architectural Heritage Management and Tourism ……........................................................................ (Assistant Professor Panjai Tantatsanawong,Ph.D.) Dean of Graduate School ............./..................../.......... The Thesis Advisor Dr. Donald Ellsmore The Thesis Examination Committee .................................................... Chairman (Professor Dr. Trungjai Buranasomphob) ............/......................../.............. .................................................... Member (Assistant Professor Pibul -

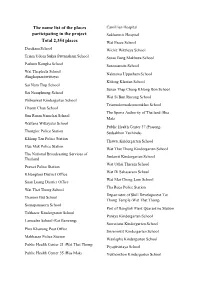

The Name List of the Places Participating in the Project

The name list of the places Camillian Hospital participating in the project: Sukhumvit Hospital Total 2,354 places Wat Pasee School Darakam School Wichit Witthaya School Triam Udom Suksa Pattanakarn School Surao Bang Makhuea School Pathum Kongka School Suraosam-in School Wat Thepleela School Naknawa Uppatham School (Singhaprasitwittaya) Khlong Klantan School Sai Nam Thip School Surao Thap Chang Khlong Bon School Sai Namphueng School Wat Si Bun Rueang School Phibunwet Kindergarten School Triamudomsuksanomklao School Chaem Chan School The Sports Authority of Thailand (Hua Sun Ruam Namchai School Mak) Wattana Wittayalai School Public Health Center 37 (Prasong- Thonglor Police Station Sudsakhon Tuchinda) Khlong Tan Police Station Thawsi Kindergarten School Hua Mak Police Station Wat That Thong Kindergarten School The National Broadcasting Services of Jindawit Kindergarten School Thailand Wat Uthai Tharam School Prawet Police Station Wat Di Sahasaram School Khlongtoei District Office Wat Mai Chong Lom School Suan Luang District Office Tha Ruea Police Station Wat That Thong School Department of Skill Development Tat Thanom But School Thong Temple (Wat That Thong) Somapanusorn School Port of Bangkok Plant Quarantine Station Tubkaew Kindergraten School Panaya Kindergarten School Lamsalee School (Rat Bamrung) Suwattana Kindergarten School Phra Khanong Post Office Srisermwit Kindergarten School Makkasan Police Station Wanlapha Kindergarten School Public Health Center 21 (Wat That Thong) Piyajitvittaya School Public Health Center 35 (Hua Mak) Yukhonthon -

Belitung Nursing Journal

Volume 7 Issue 3: May - June 2021 BELITUNG NURSING JOURNAL E-ISSN: 2477 -4073 | P-ISSN: 2528-181X Edited by: Assoc. Prof. Dr. Yupin Aungsuroch & Dr. Joko Gunawan DOI: https://doi.org/10.33546/bnj.v7i3 Review Article Implementation of nursing case management to improve community access to care: A scoping review Alenda Dwiadila Matra Putra, Ayyu Sandhi Theory and Concept Development Self-control in old age: A grounded theory study Laarni A. Caorong The development of Spiritual Nursing Care Theory using deductive axiomatic approach Ashley A. Bangcola Original Research Article Barriers to exclusive breastfeeding: A cross-sectional study among mothers in Ho Chi Minh City, Vietnam Nhan Thi Nguyen, Huong Thi Do, Nhu Thi Van Pham Influence of self-esteem, psychological empowerment, and empowering leader behaviors on assertive behaviors of staff nurses Ryan Michael F Oducado Lived experiences of Overseas Filipino Worker (OFW) nurses working in COVID-19 intensive care units Jane Marnel Pogoy, Jezyl Cempron Cutamora Symptom experience of adverse drug reaction among male and female patients with newly diagnosed pulmonary tuberculosis in Thailand Apichaya Thontham, Rapin Polsook Knowledge, attitude, and practice towards COVID-19 among student nurses in Manila, Philippines: A cross-sectional study Earl Zedrick S Quisao, Raven Rose R Tayaba, Gil P Soriano The effect of warm compresses on perineal tear and pain intensity during the second stage of labor: A randomized controlled trial Soumaya Modoor, Howieda Fouly, Hawazen Rawas DAHAGA: An Islamic spiritual -

00-Cover Tjs 38-3-60

ISSN 0125-6068 The Thai Journal of SURGERY Official Publication of the Royal College of Surgeons of Thailand www.surgeons.or.th/ejournal Volume 38 July-September 2017 Number 3 ORIGINAL ARTICLES 81 Is 5% EMLA an Effective Topical Anesthetic Agent for Replacing Intravenous Pethidine for Extracorporeal Shock Wave Lithotripsy in Patients with Renal or Upper Ureteric Calculi? Surapong Thanavongvibul 88 Effect of Bupivacaine on Preperitoneal in Laparoscopic Total Extraperitoneal Hernioplasty: Prospective Randomized Double Blind Controlled Trial Chusaeng Teerawiwatchai 94 Surgical Correction of Congenital Apical Left Ventricular Aneurysm: A Case Series Chartaroon Rimsukcharoenchai, Surin Woragidpoonpol 99 Hemorrhoidal Artery Ligation for Patients with Bleeding Tendencies: Peri-operative Outcomes Eakarach Lewthanamongkol, Jirawat Pattana-arun, Shankar Gunarasa, Supakij Khomvilai CASE REPORT 104 Agenesis of Inferior Vena Cava Associated with Acute Bilateral Common Iliac Vein Thrombosis and Hypoplastic Right Kidney (KILT Syndrome) in a 54-Year-Old Female Anuwat Chanthip ABSTRACTS 109 Abstracts of the 42nd Annual Scientific Congress of the Royal College of Surgeons of Thailand, 7-10 July 2017, Ambassador City Jomtien Hotel, Jomtien, Pattaya, Cholburi, Thailand (Part I) Secretariat Office : Royal Golden Jubilee Building, 2 Soi Soonvijai, New Petchaburi Road, Huaykwang, Bangkok 10310, Thailand Tel. +66 2716 6141-3 Fax +66 2716 6144 E-mail: [email protected] www.rcst.or.th The THAI Journal of SURGERY Official Publication of the Royal College of Surgeons of Thailand Vol. 38 July - September 2017 No. 3 Original Article Is 5% EMLA an Effective Topical Anesthetic Agent for Replacing Intravenous Pethidine for Extracorporeal Shock Wave Lithotripsy in Patients with Renal or Upper Ureteric Calculi? Surapong Thanavongvibul, MD Unit of Urology, Department of Surgery, Lerdsin Hospital Abstract Background: Patients with renal or upper ureteric calculi may require extracorporeal shock wave lithotripsy (ESWL). -

VIH: Srivichaivejvivat Public Company Limited | Annual Report 2013

Annual Report 2013 รายงานประจำป2556 Obstet dic rics-Gy opae neco rth logy O S u r g e r l y ta n e D e n i A c i l t d e e r n M a t ts iv r e o p M S e d ic in e cs C iatri osme Ped tic บริษัท ศรีวิชัย เวชวิวัฒน จำกัด (มหาชน) Srivichai Vejvivat Public Company Limited www.vichaivej.com Vichaivej International Hospital Omnoi 74/5 Phetkasem Road, Omnoi, Krathumbaen, Samutsakhon 74130 Tel. (+662) 431 0070 HOT LINE 1792 Fax: (+662) 431 0940, (+662) 431 0943 E-mail: [email protected] Vichaivej International Hospital Nongkhaem 456-456/8 Phetkasem Road, Nongkhangplu, Nongkhaem Bangkok 10160 Tel. (+662) 441 6999 Fax: (+662) 421 1784 E-mail: [email protected] Vichaivej International Hospital Samutsakhon 93/256 Sethakit1 Road, Tambon Tasai, Amphur Muang, Samutsakhon 74000 Tel. (+6634) 826 708-29 Fax: (+6634) 826 706 E-mail: [email protected] To Bang Bua Thone Mahidol University To Sanam Luang Pinklao - Nakhon Chai Si Road Pinklao - Nakhon Chai Si Road Phutthamonthon Sai 3 Road Kanchanapisek Road Central Pinklao Phutthamonthon Sai Phutthamonthon Sai ถนนพุทธมณฑลสาย 7 Tha Chin River Rai Khing Temple The Mall Bang Khae South-East Siam University Soi Mho Sri 5 Road 4 RoadAsia University Khlong San Road Joseph Upatham School Petchkasem Road Charansanitwong Road Petchkasem Road Soi Petchkasem81Soi Petchkasem 77 Soi Pongsririchai Soi Wat Thian Dat Thanachart Bank เพชรเกษม ถนนสาธร JSM Restaurant Omnoi Temple Sakorn Kasem Road Krungthonburi Road Kings Rose Garden Big C Omyai College School Setthakit 1 Road Kallaprapruk Road Ratchaphruek Road -

Improving Pharmacy Services at Lerdsin Hospital

Project Number: JRK-BKK1 Improving Pharmacy Services at Lerdsin Hospital An Interactive Qualifying Project Report Submitted to the Faculty of the WORCESTER POLYTECHNIC INSTITUTE in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Degree of Bachelor of Science by ___ Monica J. Giddings Amanda L. Gray Teri A. Hannon Date: March 3, 2005 Professor Steven Pierson, Co-Advisor Professor Robert Krueger, Co-Advisor Table of Contents Table of Contents........................................................................................................................i Abstract.................................................................................................................................... iii Executive Summary..................................................................................................................iv Introduction.......................................................................................................................iv Methodology.....................................................................................................................iv Findings..............................................................................................................................v Recommendations.............................................................................................................vi Figure A vii I. Introduction ............................................................................................................................1 II. Background ...........................................................................................................................3 -

PREFACE Rates of Cancers at Different Sites

It is a pleasure to welcome this, the fourth volume in the “Cancer in Thailand” series, bringing together the results from the population based cancer registries, for the period 1998-2000 AD (2541- 2543 BE). In this volume, there are data from nine cancer registries, including new contributions from four provinces: Nakhon Phanom and Udon Thani (North-East region), Rayong (Central region) and Prachuap Khiri Khan (Southern region). This extended coverage, both in terms of geography and population coverage (now about 27% of the national popu- lation), mean that it is possible to prepare more accurate estimates of the national cancer burden. The volume also includes the results from the first year of registration (2003) from the Thai Paediatric Oncology Group (TPOG), who have established a national register of childhood cancer based on information submitted by 20 treatment centres. The. volume concentrates, as previously, on incidence rates re- corded by the provincial registries, and the geographic variation in the PREFACE rates of cancers at different sites. In the chapters prepared by varying members of the editorial group, the observed rates for each cancer site are discussed in terms of the magnitude of the differences between reg- Vol. IV Vol. istries, and possible explanations for them. Some chapters include a : useful review of previous epidemiological studies in Thailand. The ex- tended coverage means that some previous observations can be confirmed (the high incidence of cholangiocarcinoma in all three provinces of the North-east region), or extended (the relatively higher rates of esoph- ageal cancer observed in the southern province of Songkhla pertains also to Prachuap Khiri Khan and to Rayong (central region). -

General Information Note

THE 1ST ASIA-PACIFIC MEETING ON EDUCATION 2030 25-27 November 2015, Bangkok, THAILAND General Information Note I. Venue Anantara Sathorn Bangkok Hotel 36 Narathiwat-Ratchanakarin Road Bangkok 10120 Thailand Tel: (66) 2 210 9000; Fax: (66) 2 210 9001 Email: [email protected]; [email protected] Website: www.bangkok-sathorn.anantara.com The Opening Ceremony and Plenary Sessions will be held in the Ballrooms I on the 36th Floor of the Hotel. Other function rooms of the hotel will also be used for different activities during the Conference. Details will be provided in the Conference Agenda soon. II. Registration To confirm participation in the Asia-Pacific Meeting on Education 2030 [APMED2030], all participants are requested to submit the following documents to the Conference Secretariat at [email protected]; [email protected] by 23 October 2015. 1) a completed Registration Form for all participants; 2) a copy of the Personal Information Page of the Passport of each participant Upon receipt of the completed registration from, the Secretariat will further communicate with the confirmed participants on necessary arrangements and documentation to facilitate the participation at the APMED2030. III. Travel Arrangement and Visa For UNESCO funded participants: the costs of round-trip, economy class air tickets with the most direct route will be covered. The participants shall arrange and cover other travel costs such as visa fee, transit fee, etc. Participants should ensure that their passports are valid for at least 6 months from the travel date. If a visa to Thailand is needed, the application process should start immediately.