Ligotti, Pizzolatto, and True Detective's Terrestrial Horror

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Aesthetics of the Underworld

AESTHETICS OF THE UNDERWORLD Granić, Branka Master's thesis / Diplomski rad 2020 Degree Grantor / Ustanova koja je dodijelila akademski / stručni stupanj: University of Split, Faculty of Humanities and Social Sciences, University of Split / Sveučilište u Splitu, Filozofski fakultet Permanent link / Trajna poveznica: https://urn.nsk.hr/urn:nbn:hr:172:738987 Rights / Prava: In copyright Download date / Datum preuzimanja: 2021-10-03 Repository / Repozitorij: Repository of Faculty of humanities and social sciences University of Split Faculty of Humanities and Social Sciences Department of English Language and Literature AESTHETICS OF THE UNDERWORLD MA Thesis Student: Mentor: Branka Granić Dr Simon Ryle, Asst. Prof Split, 2020 Sveučilište u Splitu Filozofski fakultet Odsjek za Engleski jezik i književnost Branka Granić ESTETIKA PODZEMLJA Diplomski rad Split, 2020 Table of Contents 1. Summary……………………………………………………………………………..4 2. Introduction ………………………………………………………………………….6 3. The underworld ……………………………………………………………………...11 4. Aesthetics …..………………………………………………………………………..16 4.1 Theory of the Uncanny, the Weird and the Eerie………………………………...19 4.2 Enlightenment ……………………………………………………………….…...22 5. Horror fiction ……………………………………………………………………...…25 5.1 Aesthetic of horror …………………………………………………………….....27 6. Arthur Machen……………………………………………………………….……….30 6.1 The concepts of aesthetics and the underworld in the work of Arthur Machen….31 7. H.P. Lovecraft ……………………………..………………………………….……...36 7.1 The concepts of aesthetics and the underworld in the work of H.P. Lovecraft…..37 -

Teaching Speculative Fiction in College: a Pedagogy for Making English Studies Relevant

Georgia State University ScholarWorks @ Georgia State University English Dissertations Department of English Summer 8-7-2012 Teaching Speculative Fiction in College: A Pedagogy for Making English Studies Relevant James H. Shimkus Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.gsu.edu/english_diss Recommended Citation Shimkus, James H., "Teaching Speculative Fiction in College: A Pedagogy for Making English Studies Relevant." Dissertation, Georgia State University, 2012. https://scholarworks.gsu.edu/english_diss/95 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Department of English at ScholarWorks @ Georgia State University. It has been accepted for inclusion in English Dissertations by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks @ Georgia State University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. TEACHING SPECULATIVE FICTION IN COLLEGE: A PEDAGOGY FOR MAKING ENGLISH STUDIES RELEVANT by JAMES HAMMOND SHIMKUS Under the Direction of Dr. Elizabeth Burmester ABSTRACT Speculative fiction (science fiction, fantasy, and horror) has steadily gained popularity both in culture and as a subject for study in college. While many helpful resources on teaching a particular genre or teaching particular texts within a genre exist, college teachers who have not previously taught science fiction, fantasy, or horror will benefit from a broader pedagogical overview of speculative fiction, and that is what this resource provides. Teachers who have previously taught speculative fiction may also benefit from the selection of alternative texts presented here. This resource includes an argument for the consideration of more speculative fiction in college English classes, whether in composition, literature, or creative writing, as well as overviews of the main theoretical discussions and definitions of each genre. -

Reminder List of Productions Eligible for the 90Th Academy Awards Alien

REMINDER LIST OF PRODUCTIONS ELIGIBLE FOR THE 90TH ACADEMY AWARDS ALIEN: COVENANT Actors: Michael Fassbender. Billy Crudup. Danny McBride. Demian Bichir. Jussie Smollett. Nathaniel Dean. Alexander England. Benjamin Rigby. Uli Latukefu. Goran D. Kleut. Actresses: Katherine Waterston. Carmen Ejogo. Callie Hernandez. Amy Seimetz. Tess Haubrich. Lorelei King. ALL I SEE IS YOU Actors: Jason Clarke. Wes Chatham. Danny Huston. Actresses: Blake Lively. Ahna O'Reilly. Yvonne Strahovski. ALL THE MONEY IN THE WORLD Actors: Christopher Plummer. Mark Wahlberg. Romain Duris. Timothy Hutton. Charlie Plummer. Charlie Shotwell. Andrew Buchan. Marco Leonardi. Giuseppe Bonifati. Nicolas Vaporidis. Actresses: Michelle Williams. ALL THESE SLEEPLESS NIGHTS AMERICAN ASSASSIN Actors: Dylan O'Brien. Michael Keaton. David Suchet. Navid Negahban. Scott Adkins. Taylor Kitsch. Actresses: Sanaa Lathan. Shiva Negar. AMERICAN MADE Actors: Tom Cruise. Domhnall Gleeson. Actresses: Sarah Wright. AND THE WINNER ISN'T ANNABELLE: CREATION Actors: Anthony LaPaglia. Brad Greenquist. Mark Bramhall. Joseph Bishara. Adam Bartley. Brian Howe. Ward Horton. Fred Tatasciore. Actresses: Stephanie Sigman. Talitha Bateman. Lulu Wilson. Miranda Otto. Grace Fulton. Philippa Coulthard. Samara Lee. Tayler Buck. Lou Lou Safran. Alicia Vela-Bailey. ARCHITECTS OF DENIAL ATOMIC BLONDE Actors: James McAvoy. John Goodman. Til Schweiger. Eddie Marsan. Toby Jones. Actresses: Charlize Theron. Sofia Boutella. 90th Academy Awards Page 1 of 34 AZIMUTH Actors: Sammy Sheik. Yiftach Klein. Actresses: Naama Preis. Samar Qupty. BPM (BEATS PER MINUTE) Actors: 1DKXHO 3«UH] %LVFD\DUW $UQDXG 9DORLV $QWRLQH 5HLQDUW] )«OL[ 0DULWDXG 0«GKL 7RXU« Actresses: $GªOH +DHQHO THE B-SIDE: ELSA DORFMAN'S PORTRAIT PHOTOGRAPHY BABY DRIVER Actors: Ansel Elgort. Kevin Spacey. Jon Bernthal. Jon Hamm. Jamie Foxx. -

NYU.1287 Style Guide 5.13

C U L photography T BRIGHT NIGHTS PHOTOGRAPHER LYNN SAVILLE SEES NEW YORK CITY IN A CERTAIN LIGHT by Nicole Pezold / GSAS ’04 UR hotographer Lynn celli), bestows them with an decades worth of nighttime im - E Saville generally unexpected beauty. Luminous ages, much of them focused on works alone. With blues, from desert turquoise to the city’s architecture, and pieces P a small, collapsible cobalt, accented with pinks, or - from her oeuvre grace the col - tripod and two anges, and amber, highlight emp - lections of the Brooklyn Muse - cameras, she scouts New York ty rail yards, loading docks, shells um and the New York Public City’s unpopulated, weed- of warehouses, the bellies of Library. Art critic Arthur Danto, choked fringes, from Gowanus in overpasses, and elevated subway in Night/Shift ’s introduction, Brooklyn to Hunts Point in the platforms. Saville admits she felt compares her to Eugène Atget, Bronx, by both bus and foot. She some urgency to record these the ambitious photographer who may wander up and down a des - streetscapes because—even in the documented Paris’s empty streets olate block absorbed by angles midst of a recession—it seems in the early 20th century. and, especially, points of illumi - only a matter of time before Saville is no preservationist. nation. She shoots at twilight, they’re claimed for condos, bank She was trained at the Pratt Insti - when the sky fades in cinematic branches, and Duane Reades. “I tute as a street photographer. In tension with freshly lit street love the way the city looks now the vein of celebrated artists An - lamps and floodlights. -

To Download The

FREE EXAM Complete Physical Exam Included New Clients Only Must present coupon. Offers cannot be combined Wellness Plans Extended Hours Multiple Locations www.forevervets.com4 x 2” ad Your Community Voice for 50 Years PONTEYour Community Voice VED for 50 YearsRA RRecorecorPONTE VEDRA dderer entertainment EEXXTRATRA! ! Featuring TV listings, streaming information, sports schedules, puzzles and more! December 3 - 9, 2020 Sample sale: INSIDE: Offering: 1/2 off Hydrafacials Venus Legacy What’s new on • Treatments Netflix, Hulu & • BOTOX Call for details Amazon Prime • DYSPORT Pages 3, 17 & 22 • RF Microneedling • Body Contouring • B12 Complex • Lipolean Injections • Colorscience Products • Alastin Skincare Judge him if you must: Bryan Cranston Get Skinny with it! (904) 999-0977 plays a troubled ‘Your Honor’ www.SkinnyJax.comwww.SkinnyJax.com Bryan Cranston stars in the Showtime drama series “Your Honor,” premiering Sunday. 1361 13th Ave., Ste.1 x140 5” ad Jacksonville Beach NowTOP 7 is REASONS a great timeTO LIST to YOUR HOMEIt will WITH provide KATHLEEN your home: FLORYAN List Your Home for Sale • YOUComplimentary ALWAYS coverage RECEIVE: while the home is listed 1) MY UNDIVIDED ATTENTION – • An edge in the local market Kathleen Floryan LIST IT becauseno delegating buyers toprefer a “team to purchase member” a Broker Associate home2) A that FREE a HOMEseller stands SELLER behind WARRANTY • whileReduced Listed post-sale for Sale liability with [email protected] UNDER CONTRACT - DAY 1 ListSecure® 904-687-5146 WITH ME! 3) A FREE IN-HOME STAGING https://www.kathleenfloryan.exprealty.com PROFESSIONAL Evaluation BK3167010 I will provide you a FREE https://expressoffers.com/exp/kathleen-floryan 4) ACCESS to my Preferred Professional America’s Preferred Services List Ask me how to get cash offers on your home! 5) AHome 75 Point SELLERS Warranty CHECKLIST for for Preparing Your Home for Sale 6) ALWAYSyour Professionalhome when Photography we put– 3D, Drone, Floor Plans & More 7) Ait Comprehensive on the market. -

Cineclub En El Teatro De Rojas

Cineclub en el Teatro De Rojas CICLO: "JÓVENES" Febrero 2010 - Mayo 2010 • «PARANOID PARK» ( +) 22, 23 y 24 de Febrero Pases a las 19:00 y 22:00 horas. Precio: 3 € o DIRECCIÓN: GUST VAN SANT o GUIÓN: Gust van Sant, según la novela de Blake Nelson. o FOTOGRAFÍA: Christopher Doyle y Rain Kathyli. o MÚSICA: Varios. o MONTAJE: Gusta van Sant. o INTÉRPRETES: Gabe Nevis (Alex), Taylor Momsen (Jennifer), Jake Millier (Jared), Daniel Liv (detective Richard Lu). o NACIONALIDAD: USA-Francia, 2007. o DURACIÓN: 185 min. o Premio 60 Aniversario del Festival de Cannes 2008. o Premio al Productor –Neil Kopp– en los Independent Spirit Awards. • «EX» ( +) 1, 2 Y 3 de Marzo Pases a las 19:00 y 22:00 horas. Precio: 3 € o DIRECCIÓN: FAUSTO BRIZZI. o GUIÓN: Brizzi, Massimiliano Bruno y Marco Martani. o FOTOGRAFÍA: Marcello Montarsi. o MÚSICA: Bruno Zambrini. o MONTAJE: Luciana Pandolfelli. o INTÉRPRETES: Claudio Bisio (Sergio), Nancy Brilli (Caterina), Cristiana Capotondi (Giulia), Cécile Cassel (Monique). o NACIONALIDAD: Italia-Francia, 2009. o DURACIÓN: 120 min. • «RESACÓN EN LAS VEGAS» (The Hangover)( +) 8, 9 y 10 de Marzo Pases a las 19:00 y 22:00 horas. Precio: 3 € o DIRECCIÓN: TODD PHILLIPS. o GUIÓN: Jon Lucas y Scott Moore. o FOTOGRAFÍA: Lawrence Sher. o MÚSICA: Christophe Beck. o MONTAJE: Debra Neil-Fisher. o INTÉRPRETES: Bradley Cooper (Phil Wenneck), Ed Helmes (Stu Price), Zach Galafianakis (Alan Garner), Heather Graham (Jade), Justin Bartha (Doug Billing). o NACIONALIDAD: USA, 2009. o DURACIÓN: 100 min. • «FROZEN RIVER» ( +) 15, 16 y 17 de Marzo Pases a las 19:00 y 22:00 horas. -

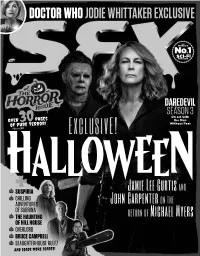

SFX’S Horror Columnist Peers Into If You’Re New to the Netflix Catherine Zeta-Jones Movie

DOCTOR WHO JODIE WHITTAKER EXCLUSIVE SCI-FI 306 DAREDEVIL SEASON 3 On set with Over 30 pages the Man of pure terror! Without Fear featuring EXCLUSIVE! HALLOWEEN Jamie Lee Curtis and SUSPIRIA CHILLING John Carpenter on the ADVENTURES OF SABRINA return of Michael Myers THE HAUNTING OF HILL HOUSE OVERLORD BRUCE CAMPBELL SLAUGHTERHOUSE RULEZ AND LOADS MORE SCARES! ISSUE 306 NOVEMBER Contents2018 34 56 61 68 HALLOWEEN CHILLING DRACUL DOCTOR WHO Jamie Lee Curtis and John ADVENTURES Bram Stoker’s great-grandson We speak to the new Time Lord Carpenter tell us about new OF SABRINA unearths the iconic vamp for Jodie Whittaker about series 11 Michael Myers sightings in Remember Melissa Joan Hart another toothsome tale. and her Heroes & Inspirations. Haddonfield. That place really playing the teenage witch on CITV needs a Neighbourhood Watch. in the ’90s? Well this version is And a can of pepper spray. nothing like that. 62 74 OVERLORD TADE THOMPSON A WW2 zombie horror from the The award-winning Rosewater 48 56 JJ Abrams stable and it’s not a author tells us all about his THE HAUNTING OF Cloverfield movie? brilliant Nigeria-set novel. HILL HOUSE Shirley Jackson’s horror classic gets a new Netflix treatment. 66 76 Who knows, it might just be better PENNY DREADFUL DAREDEVIL than the 1999 Liam Neeson/ SFX’s horror columnist peers into If you’re new to the Netflix Catherine Zeta-Jones movie. her crystal ball to pick out the superhero shows, this third season Fingers crossed! hottest upcoming scares. is probably a bad place to start. -

ENC 1145 3309 Chalifour

ENC 1145: Writing About Weird Fiction Section: 3309 Time: MWF Period 8 (3:00-3:50 pm) Room: Turlington 2349 Instructor: Spencer Chalifour Email: [email protected] Office: Turlington 4315 Office Hours: W Period 7 and by appointment Course Description: In his essay “Supernatural Horror in Fiction,” H.P. Lovecraft defines the weird tale as having to incorporate “a malign and particular suspension or defeat of those fixed laws of Nature which are our only safeguard against the assaults of chaos and the daemons of unplumbed space.” This course will focus on “weird fiction,” a genre originating in the late 19th century and containing elements of horror, fantasy, science fiction, and the macabre. In our examination of weird authors spanning its history, we will attempt to discover what differentiates weird fiction from similar genres and will use several theoretical and historical lenses to examine questions regarding what constitutes “The Weird.” What was the cultural and historical context for the inception of weird fiction? Why did British weird authors receive greater literary recognition than their American counterparts? Why since the 1980s are we experiencing a resurgence of weird fiction through the New Weird movement, and how do these authors continue the themes of their predecessors into the 21st century? Readings for this class will span from early authors who had a strong influence over later weird writers (like E.T.A. Hoffman and Robert Chambers) to the weird writers of the early 20th century (like Lovecraft, Robert Howard, Clark Ashton Smith, Lord Dunsany, and Algernon Blackwood) to New Weird authors (including China Miéville, Thomas Ligotti, and Laird Barron). -

2012 Twenty-Seven Years of Nominees & Winners FILM INDEPENDENT SPIRIT AWARDS

2012 Twenty-Seven Years of Nominees & Winners FILM INDEPENDENT SPIRIT AWARDS BEST FIRST SCREENPLAY 2012 NOMINEES (Winners in bold) *Will Reiser 50/50 BEST FEATURE (Award given to the producer(s)) Mike Cahill & Brit Marling Another Earth *The Artist Thomas Langmann J.C. Chandor Margin Call 50/50 Evan Goldberg, Ben Karlin, Seth Rogen Patrick DeWitt Terri Beginners Miranda de Pencier, Lars Knudsen, Phil Johnston Cedar Rapids Leslie Urdang, Dean Vanech, Jay Van Hoy Drive Michel Litvak, John Palermo, BEST FEMALE LEAD Marc Platt, Gigi Pritzker, Adam Siegel *Michelle Williams My Week with Marilyn Take Shelter Tyler Davidson, Sophia Lin Lauren Ambrose Think of Me The Descendants Jim Burke, Alexander Payne, Jim Taylor Rachael Harris Natural Selection Adepero Oduye Pariah BEST FIRST FEATURE (Award given to the director and producer) Elizabeth Olsen Martha Marcy May Marlene *Margin Call Director: J.C. Chandor Producers: Robert Ogden Barnum, BEST MALE LEAD Michael Benaroya, Neal Dodson, Joe Jenckes, Corey Moosa, Zachary Quinto *Jean Dujardin The Artist Another Earth Director: Mike Cahill Demián Bichir A Better Life Producers: Mike Cahill, Hunter Gray, Brit Marling, Ryan Gosling Drive Nicholas Shumaker Woody Harrelson Rampart In The Family Director: Patrick Wang Michael Shannon Take Shelter Producers: Robert Tonino, Andrew van den Houten, Patrick Wang BEST SUPPORTING FEMALE Martha Marcy May Marlene Director: Sean Durkin Producers: Antonio Campos, Patrick Cunningham, *Shailene Woodley The Descendants Chris Maybach, Josh Mond Jessica Chastain Take Shelter -

35 Years of Nominees and Winners 36

3635 Years of Nominees and Winners 2021 Nominees (Winners in bold) BEST FEATURE JOHN CASSAVETES AWARD BEST MALE LEAD (Award given to the producer) (Award given to the best feature made for under *RIZ AHMED - Sound of Metal $500,000; award given to the writer, director, *NOMADLAND and producer) CHADWICK BOSEMAN - Ma Rainey’s Black Bottom PRODUCERS: Mollye Asher, Dan Janvey, ADARSH GOURAV - The White Tiger Frances McDormand, Peter Spears, Chloé Zhao *RESIDUE WRITER/DIRECTOR: Merawi Gerima ROB MORGAN - Bull FIRST COW PRODUCERS: Neil Kopp, Vincent Savino, THE KILLING OF TWO LOVERS STEVEN YEUN - Minari Anish Savjani WRITER/DIRECTOR/PRODUCER: Robert Machoian PRODUCERS: Scott Christopherson, BEST SUPPORTING FEMALE MA RAINEY’S BLACK BOTTOM Clayne Crawford PRODUCERS: Todd Black, Denzel Washington, *YUH-JUNG YOUN - Minari Dany Wolf LA LEYENDA NEGRA ALEXIS CHIKAEZE - Miss Juneteenth WRITER/DIRECTOR: Patricia Vidal Delgado MINARI YERI HAN - Minari PRODUCERS: Alicia Herder, Marcel Perez PRODUCERS: Dede Gardner, Jeremy Kleiner, VALERIE MAHAFFEY - French Exit Christina Oh LINGUA FRANCA WRITER/DIRECTOR/PRODUCER: Isabel Sandoval TALIA RYDER - Never Rarely Sometimes Always NEVER RARELY SOMETIMES ALWAYS PRODUCERS: Darlene Catly Malimas, Jhett Tolentino, PRODUCERS: Sara Murphy, Adele Romanski Carlo Velayo BEST SUPPORTING MALE BEST FIRST FEATURE SAINT FRANCES *PAUL RACI - Sound of Metal (Award given to the director and producer) DIRECTOR/PRODUCER: Alex Thompson COLMAN DOMINGO - Ma Rainey’s Black Bottom WRITER: Kelly O’Sullivan *SOUND OF METAL ORION LEE - First -

True Detective and the States of American Wound Culture

True Detective and the States of American Wound Culture RODNEY TAVEIRA “Criminals should be publically displayed ... at the frontiers of the country.” Plato (qtd. in Girard 298) HE STATE INSTITUTIONS PORTRAYED IN THE HBO CRIME PROCEDU- ral True Detective are innately and structurally corrupt. Local T mayors’, state governors’, and district attorneys’ offices, city and county police, and sheriff’s departments commit and cover up violent crimes. These offices and departments comprise mostly mid- dle-aged white men. Masculinist desires for power and domination manifest as interpersonal ends and contact points between the indi- vidual and the state. The state here is a mutable system, both abstract and concrete. It encompasses the functions of the legal and political offices whose corruption is taken for granted in their shady rela- tions to criminal networks, commercial enterprises, and religious institutions. There is nothing particularly novel about this vision of the state. Masculinist violence and institutional corruption further damage vic- tims in the system (typically women, children, and disempowered and disenfranchised others, like migrant workers) who need a hero to solve the crimes committed against them—these tropes are staples of detective fiction, film noir, and many television crime procedurals. What then explains the popular and critical success of True Detective? Moreover, what does the show’s representation of the state—its aes- thetic strategies, narratives, and images—reveal about contemporary The Journal of Popular Culture, Vol. 50, No. 3, 2017 © 2017 Wiley Periodicals, Inc. 585 586 Rodney Taveira understandings and imaginings of the state, the individual, and the relations between them? While tracing the complex entanglement of the entertainment industries with femicidal and spectacular violence within a critical regionalism, carried out through digital modes of distribution, one can also see how government agencies shape content. -

The Honorable Mitch Mcconnell the Honorable Nancy Pelosi Majority Leader, U.S. Senate Speaker, U.S. House of Representatives Wa

The Honorable Mitch McConnell The Honorable Nancy Pelosi Majority Leader, U.S. Senate Speaker, U.S. House of Representatives Washington, DC 20510 Washington, DC 20515 The Honorable Charles Schumer The Honorable Kevin McCarthy Democratic Leader, U.S. Senate Republican Leader, U.S. House of Representatives Washington, DC 20510 Washington, DC 20515 September 30, 2020 Dear Leader McConnell, Speaker Pelosi, Leader Schumer, and Leader McCarthy: Thank you for your leadership at this challenging time for our country. As you consider forthcoming COVID-19 relief legislation, we ask you to prioritize assistance for the hardest-hit industries, like our country’s beloved movie theaters. No doubt you are hearing from many, many businesses that need relief. Movie theaters are in dire straits, and we urge you to redirect unallocated funds from the CARES Act to proposals that help businesses that have suffered the steepest revenue drops due to the pandemic, or to enact new proposals such as the RESTART Act (S. 3814/H.R. 7481). Absent a solution designed for their circumstances, theaters may not survive the impact of the pandemic. The pandemic has been a devastating financial blow to cinemas. 93% of movie theater companies had over 75% in losses in the second quarter of 2020. If the status quo continues, 69% of small and mid-sized movie theater companies will be forced to file for bankruptcy or to close permanently, and 66% of theater jobs will be lost. Our country cannot afford to lose the social, economic, and cultural value that theaters provide. The moviegoing experience is central to American life.