Learning Language and Literacy

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Literacy in India: the Gender and Age Dimension

OCTOBER 2019 ISSUE NO. 322 Literacy in India: The Gender and Age Dimension TANUSHREE CHANDRA ABSTRACT This brief examines the literacy landscape in India between 1987 and 2017, focusing on the gender gap in four age cohorts: children, youth, working-age adults, and the elderly. It finds that the gender gap in literacy has shrunk substantially for children and youth, but the gap for older adults and the elderly has seen little improvement. A state-level analysis of the gap reveals the same trend for most Indian states. The brief offers recommendations such as launching adult literacy programmes linked with skill development and vocational training, offering incentives such as employment and micro-credit, and leveraging technology such as mobile-learning to bolster adult education, especially for females. It underlines the importance of community participation for the success of these initiatives. Attribution: Tanushree Chandra, “Literacy in India: The Gender and Age Dimension”, ORF Issue Brief No. 322, October 2019, Observer Research Foundation. Observer Research Foundation (ORF) is a public policy think tank that aims to influence the formulation of policies for building a strong and prosperous India. ORF pursues these goals by providing informed analyses and in-depth research, and organising events that serve as platforms for stimulating and productive discussions. ISBN 978-93-89622-04-1 © 2019 Observer Research Foundation. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, copied, archived, retained or transmitted through print, speech or electronic media without prior written approval from ORF. Literacy in India: The Gender and Age Dimension INTRODUCTION “neither in terms of absolute levels of literacy nor distributive justice, i.e., reduction in gender Literacy is one of the most essential indicators and caste disparities, does per capita income of the quality of a country’s human capital. -

Literacy UN Acked: What DO WE MEAN by Literacy?

Memo 4 | Fall 2012 LEAD FOR LITERACY MEMO Providing guidance for leaders dedicated to children's literacy development, birth to age 9 L U: W D W M L? The Issue: To make decisions that have a positive What Competencies Does a Reader Need to impact on children’s literacy outcomes, leaders need a Make Sense of This Passage? keen understanding of literacy itself. But literacy is a complex concept and there are many key HIGH-SPEED TRAINS* service that moved at misunderstandings about what, exactly, literacy is. A type of high-speed a speed of one train was first hundred miles per Unpacking Literacy Competencies hour. Today, similar In this memo we focus specifically on two broad introduced in Japan about forty years ago. Japanese trains are categories of literacy competencies: skills‐based even faster, traveling The train was low to competencies and knowledge‐based competencies. at speeds of almost the ground, and its two hundred miles nose looked somewhat per hour. There are like the nose of a jet. Literacy many reasons that These trains provided high-speed trains are Reading, Wring, Listening & Speaking the first passenger popular. * Passage adapted from Good & Kaminski (2007) Skills Knowledge Dynamic Indicators of Basic Early Literacy Skills, 6th ed. ‐ Concepts about print ‐ Concepts about the ‐ The ability to hear & world Map sounds onto letters (e.g., /s/ /p/ /ee/ /d/) work with spoken sounds ‐ The ability to and blend these to form a word (speed) ‐ Alphabet knowledge understand & express Based ‐ Word reading complex ideas ‐ Recognize -

Dyslexia and Structured Literacy Fact Sheet

Dyslexia and Structured Literacy Fact Sheet Written by Belinda Dekker Dyslexia Support Australia https://dekkerdyslexia.wordpress.com/ Structured Literacy • Structured literacy is a scientifically researched based approach to the teaching of reading. Structured literacy can be in the form of teachers trained in the use of structured literacy methodologies and programs that adhere to the fundamental and essential components of structured literacy. • Structure means that there is a step by step clearly defined systematic process to the teaching of reading. Including a set procedure for introducing, reviewing and practicing essential concepts. Concepts have a clearly defined sequence from simple to more complex. Each new concept builds upon previously introduced concepts. • Knowledge is cumulative and the program or teacher will use continuous assessment to guide a student’s progression to the next clearly defined step in the program. An important fundamental component is the automaticity of a concept before progression. • Skills are explicitly or directly taught to the student with clear explanations, examples and modelling of concepts. ‘The term “Structured Literacy” is not designed to replace Orton Gillingham, Multi-Sensory or other terms in common use. It is an umbrella term designed to describe all of the programs that teach reading in essentially the same way'. Hal Malchow. President, International Dyslexia Association A Position Statement on Approaches to Reading Instruction Supported by Learning Difficulties Australia "LDA supports approaches to reading instruction that adopt an explicit structured approach to the teaching of reading and are consistent with the scientific evidence as to how children learn to read and how best to teach them. -

Orton-Gillingham Or Multisensory Structured Language Approaches

JUST THE FACTS... Information provided by The International Dyslexia Association® ORTON-GILLINGHAM-BASED AND/OR MULTISENSORY STRUCTURED LANGUAGE APPROACHES The principles of instruction and content of a Syntax: Syntax is the set of principles that dictate the multisensory structured language program are essential sequence and function of words in a sentence in order for effective teaching methodologies. The International to convey meaning. This includes grammar, sentence Dyslexia Association (IDA) actively promotes effective variation, and the mechanics of language. teaching approaches and related clinical educational Semantics: Semantics is that aspect of language intervention strategies for dyslexics. concerned with meaning. The curriculum (from the beginning) must include instruction in the CONTENT: What Is Taught comprehension of written language. Phonology and Phonological Awareness: Phonology is the study of sounds and how they work within their environment. A phoneme is the smallest unit of sound PRINCIPLES OF INSTRUCTION: How It Is Taught in a given language that can be recognized as being Simultaneous, Multisensory (VAKT): Teaching is distinct from other sounds in the language. done using all learning pathways in the brain Phonological awareness is the understanding of the (visual/auditory, kinesthetic-tactile) simultaneously in internal linguistic structure of words. An important order to enhance memory and learning. aspect of phonological awareness is phonemic awareness or the ability to segment words into their Systematic and Cumulative: Multisensory language component sounds. instruction requires that the organization of material follows the logical order of the language. The Sound-Symbol Association: This is the knowledge of sequence must begin with the easiest and most basic the various sounds in the English language and their elements and progress methodically to more difficult correspondence to the letters and combinations of material. -

Structured Literacy and the SIPPS® Program

Structured Literacy and the SIPPS® Program The International Dyslexia Association identifies Structured Literacy as an effective instructional approach for meeting the needs of students who struggle with learning to read. Structured Literacy utilizes systematic, explicit instruction to teach decoding skills including phonology, sound-symbol association, syllable types, morphology, syntax, and semantics. Structured Literacy instruction has been around for over a century and is sometimes referred to as systematic reading instruction, phonics-based reading instruction, the Orton-Gillingham Approach, or synthetic phonics, among other names. The SIPPS (Systematic Instruction in Phonological Awareness, Phonics, and Sight Words) program, developed by Dr. John Shefelbine, is a multilevel program that develops the word-recognition strategies and skills that enable students to become independent and confident readers and writers. Dr. Shefelbine’s research emphasizes systematic instruction, and in many ways parallels the Orton-Gillingham Approach. Structured Literacy The table below notes the elements of Structured Literacy aligned to the SIPPS program. Elements of Structured Literacy SIPPS Phonology Defined as the study of sound structure of spoken Phonological awareness activities appear in every words; includes rhyming, counting words in lesson in SIPPS Beginning, Extension, and Plus. spoken sentences, clapping syllables in spoken These activities begin with segmenting and words, and phonemic awareness (manipulation of blending, include rhyme, and increase in complexity sounds). to dropping and substituting phonemes. Sound-Symbol Association Defined as connecting sounds to print, including Spelling-sounds are explicitly taught throughout the blending and segmenting. This should occur two program. Sounds are taught in order of utility, which ways: visual to auditory (reading) and auditory to allows students to quickly begin to read connected visual (spelling). -

An Investigation Into Definitions of English As a Subject and the Relationship Between English, Literacy and ‘Being Literate’

What is literacy? An investigation into definitions of English as a subject and the relationship between English, literacy and ‘being literate’ A Research Report Commissioned by Cambridge Assessment January 2013 Contents 1 Introduction ........................................................................................................................................................ 3 2 How definitions of English as a school subject have evolved ............................................................................ 4 2.1 English in the 20th century ........................................................................................................................ 4 2.2 The impact of The National Literacy Strategy ........................................................................................... 6 2.3 Current concerns about English ................................................................................................................ 6 3 Literacy ............................................................................................................................................................... 8 3.1 Definitions of literacy ................................................................................................................................. 8 3.2 Literacy across the world......................................................................................................................... 10 3.3 Literacy – a high-stakes issue in other countries ................................................................................... -

L2 Literacies and Teachers' Work in the Context of High-Stakes School Reform

Available online at www.sciencedirect.com Journal of Second Language Writing 17 (2008) 274–291 Teachers as critical text analysts: L2 literacies and teachers’ work in the context of high-stakes school reform Meg Gebhard a,*, Jan Demers b, Zoe¨ Castillo-Rosenthal b a University of Massachusetts, 74 January Hills Road, Amherst, MA 01002, United States b Amherst Public Schools, United States Abstract The authors describe the professional development of L1 and L2 teachers from a comprehensive theoretical perspective that focuses on literacy as a critical social practice, the construction of student/teacher knowledge, and institutional forces that support and/or constrain the academic literacy development of L2 students in the United States. The authors begin with an articulation of the theoretical framework guiding this discussion. Next, they describe how this perspective was enacted in a graduate program designed to support K-12 teachers in developing an understanding of theories, research, and practices that form a critical approach to L2 academic literacy development. Last, following Hyland (2003, 2007), the authors reflect on the challenges, and ultimately the necessity, of critically reconceptualizing L1 and L2 teacher education to include greater attention to genre theory and genre-based pedagogies. This call for a reconceptualization of teacher education in the United States is warranted because of the combined impact of economic, demographic, and educational policies shaping the work of teachers and the literacy practices of L2 students. # 2008 Elsevier Inc. All rights reserved. Keywords: L2 literacy; English language learners; Teachers professional development; Critical discourse analysis; Genre-based pedagogy In their introductory remarks to a special edition of the Journal of Second Language Writing focusing on teacher education, Hirvela and Belcher (2007) maintain that many L2 writing scholars have not foregrounded the important role they play as ‘‘teachers of teachers of writing’’ (p. -

Evidence Based Practice: Visual Motor Integration for Building Literacy: the Role of Occupational Therapy Francis, T., & Beck, C

Evidence Based Practice: Visual Motor Integration for Building Literacy: The Role of Occupational Therapy Francis, T., & Beck, C. (2018). Visual Motor Integration for Building Literacy: The Role of Occupational Therapy. OT Practice 23(15), 14–18. The Research: Occupational therapy interventions for visual processing skills were found to positively affect academic achievement and social participation. Key elements of intervention activities needed for progress include: fine motor activities, copying skills, gross motor activities, and a high level of cognitive interaction with completing activities. What is it? Visual information processing skills refers to “a group of visual cognitive skills used for extracting and organizing visual information from the environment and integrating this information with other sensory modalities and higher cognitive functions”. Visual information processing skills are divided into three components: visual spatial, visual analysis, and visual motor. Visual motor integration skills (i.e. eye-hand coordination) are related to an individual’s ability to combine visual information processing skills with fine motor or gross motor movement. Studies have found that visual motor integration is a component of reading skills in children in elementary school Specific Combination of Intervention Strategies Found to be Successful Fine motor activities ● Intervention activities: Manipulating small items (e.g., beads, coins); opening the thumb web space, separating the two sides of the hand; practicing finger isolation; -

Abdul-Hakim, I

African American English Bibliography A Abdul-Hakim, I. (2002). Florida preservice teachers' attitudes toward African-American Vernacular English. (Doctoral dissertation, The Florida State University, 2002), Dissertation Abstracts International 64(10). (AAT 3109259) Abrahams, R. D. (1962). Playing the dozens. Journal of American Folklore, 75, 209-218. Abrahams, R. D. (1964). Deep down in the jungle...: Negro narrative folklore from the streets of Philadelphia. Hatboro, PA: Folklore Associates. Abrahams, R. D. (1970). Rapping and capping: Black talk as art. In J. F. Szwed (Ed.), Black American (pp. 132-142). New York: Basic Books, Inc. Abrahams, R. D. (1972). Joking: The training of the man of words in talking broad. In T. Kochman (Ed.), Rappin' and stylin' out: Communication in black America (pp. 215-240). Urbana, IL: University of Illinois Press. Abrahams, R. D. (1974). Black talking on the streets. In R. Bauman & J. Sherzer (Eds.), Explorations in the ethnography of speaking (pp. 240-262). London: Cambridge University Press. Abrahams, R. D. (1975). Negotiating respect: Patterns of presentation among black women. In C. R. Farrer (Ed.), Women and folklore (pp. 58-80). Austin: University of Texas Press. Abrahams, R. D. (1976). Talking black. Rowley, MA: Newbury House. Abrahams, R. D. (1993). Black talking on the streets. In L. M. Cleary & M. D. Linn (Eds.), Linguistics for teachers (pp. 173-198). New York: McGraw-Hill. Adams, T. M., & Fuller, D. B. (2006). The words have changed but the ideology remains the same: Misogynistic lyrics in rap music. Journal of Black Studies, 36(6), 938- 957. Adger, C. T. (1994). Enhancing the delivery of services to black special education students from non-standard English backgrounds. -

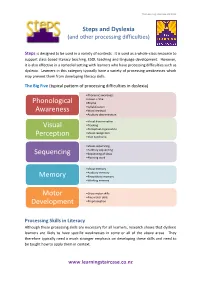

Phonological Awareness Visual Perception Sequencing Memory

The Learning Staircase Ltd 2012 Steps and Dyslexia (and other processing difficulties) Steps is designed to be used in a variety of contexts. It is used as a whole-class resource to support class-based literacy teaching, ESOL teaching and language development. However, it is also effective in a remedial setting with learners who have processing difficulties such as dyslexia. Learners in this category typically have a variety of processing weaknesses which may prevent them from developing literacy skills. The Big Five (typical pattern of processing difficulties in dyslexia) •Phonemic awareness •Onset + rime Phonological •Rhyme •Syllabification Awareness •Word retrieval •Auditory discrimination •Visual discrimination Visual •Tracking •Perceptual organisation •Visual recognition Perception •Irlen Syndrome •Visual sequencing •Auditory sequencing Sequencing •Sequencing of ideas •Planning work •Visual memory •Auditory memory Memory •Kinaesthetic memory •Working memory Motor •Gross motor skills •Fine motor skills Development •Proprioception Processing Skills in Literacy Although these processing skills are necessary for all learners, research shows that dyslexic learners are likely to have specific weaknesses in some or all of the above areas. They therefore typically need a much stronger emphasis on developing these skills and need to be taught how to apply them in context. www.learningstaircase.co.nz The Learning Staircase Ltd 2012 However, there are further aspects which are important, particularly for learners with literacy difficulties, such as dyslexia. These learners often need significantly more reinforcement. Research shows that a non-dyslexic learner needs typically between 4 – 10 exposures to a word to fix it in long-term memory. A dyslexic learner, on the other hand, can need 500 – 1300 exposures to the same word. -

Adolescent Literacy Addressing the Needs of Students in Grades 4–12

Adolescent Literacy Addressing the Needs of Students in Grades 4–12 By Joan Sedita Literacy skills in the 21st century are more essential than ever for success in education, work, citizenship, and our personal lives. However, far too many older students and adults do not have the necessary reading and writing skills to succeed in postsecondary education or the ever-increasing number of jobs that require strong literacy skills. During the 1990s and through 2008, significant emphasis was placed on the use of research to determine how children learn to read and why some students struggle with reading. Early literacy achievement, however, is not necessarily a guarantee that literacy skills will continue to grow as students move beyond Grade 3. In Reading Next, it is noted that: Recent National Assessment of Educational Progress (NAEP) reading results indicate that efforts to improve K–3 literacy are paying off at the 4th-grade level, but these improvements do not necessarily translate into better achievement among adolescents… Comparing the most recent NAEP results for all three grade levels (i.e., 4, 8, and 12) to those from 1992, the percentage of students scoring proficient has significantly improved among 4th graders, but not among 8th and 12th graders. (Biancarosa & Snow, 2006, pp. 7–8) Scores at the secondary level, where there has been relatively little investment, have remained flat since the 1970s (Heller & Greenleaf, 2007). The following observation from Time to Act: An Agenda for Advancing Adolescent Literacy for College and Career Success sums up the challenges faced after Grade 3: The truth is that good early literacy instruction does not inoculate students against struggle or failure later on. -

1 Writing Systems and Orthographies Volume 2: Literacy Barbara Burnaby the Ontario Institute for Studies in Education

Writing Systems and Orthographies Volume 2: Literacy Barbara Burnaby The Ontario Institute for Studies in Education 1 Introduction Academic discussion of writing systems (grammatology) extends to both detailed descriptions of the mechanics of particular systems and/or visceral theoretical debates involving linguistics, anthropology, archaeology, sociology, history, and/or psychology. Issues are raised concerning competing views of reality (e.g. Street, 1984, p. 130) and the power of Western thought in relation to non-Western knowledge and its dissemination (e.g. DeFrancis, 1989, p. xi). This review of literature leans towards cross-national and comparative studies, although it is biassed by the writer's limitation to works in English. Under the headings of definitions, typologies, values, first and second language literacy learning, and other factors, it only touches the surface of a massive body of work. What is a Writing System? Stubbs (1980, p. viii) rather dramatically states ...there is...nothing approaching a coherent theory about the relations between reading and writing, or between written and spoken language, or about the place of written language in society and the purposes it serves. 2 Authors generally agree with Gelb (1963, p. 12) that writing is `a system of human intercommunication by means of conventional visible marks' (italics in the original). If one construes `marks' liberally, body sign languages (as in sign languages used by the deaf) can be included, and the definition encompasses systems such as musical notation and those that indicate kinesics (e.g. Basso & Anderson, 1977). Gauer, equating writing with information storage, takes this stance (1984, p. 14). Many others (e.g.