Punk As Public, Punks As Texts: Some of This Is True

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Fray Over My Head Cable Car Sheet Music

Fray Over My Head Cable Car Sheet Music Download fray over my head cable car sheet music pdf now available in our library. We give you 2 pages partial preview of fray over my head cable car sheet music that you can try for free. This music notes has been read 3202 times and last read at 2021-09-28 18:00:27. In order to continue read the entire sheet music of fray over my head cable car you need to signup, download music sheet notes in pdf format also available for offline reading. Instrument: Drum Set, Percussion Ensemble: Mixed Level: Beginning [ READ SHEET MUSIC ] Other Sheet Music Over My Head Cable Car Intermediate Piano Over My Head Cable Car Intermediate Piano sheet music has been read 2443 times. Over my head cable car intermediate piano arrangement is for Intermediate level. The music notes has 3 preview and last read at 2021-09-27 17:09:19. [ Read More ] Into The Fray Into The Fray sheet music has been read 3653 times. Into the fray arrangement is for Intermediate level. The music notes has 4 preview and last read at 2021-09-28 06:13:13. [ Read More ] You Found Me Aka Amistad The Fray String Quartet You Found Me Aka Amistad The Fray String Quartet sheet music has been read 3015 times. You found me aka amistad the fray string quartet arrangement is for Intermediate level. The music notes has 6 preview and last read at 2021-09-28 14:48:35. [ Read More ] How To Save A Life By The Fray Arranged For String Quartet How To Save A Life By The Fray Arranged For String Quartet sheet music has been read 4302 times. -

'Judas Priest-On Tour' Violators Attacked

MARCH 18, 1978 VOL. 1, NO. 1 Benefiting FREE San Antonio For Your Austin• Houston Entertainment ~ 'Judas Priest-On Tour' JC 35296 The high priest of heavy rock 'n' roll with their inimitable style grace our shores once again. To change or not to change. That is what a rock and roll band must deal with. A group may develop a success ful formula for its music, which leads to personal and/ or commercial contentment. Musicians, upon reach ing this point, find their music evolving in a new direction or continuing their successful format. Judas Priest has choosen the security of proven success. Their first two ViolatorsAttacked domestic albums were well See story on page 10 received in this area. With the release of a new album "Stained Class" and • Elvis Costello an upcoming concert March INSIDETHIS • Radio Survey 24 their claim to fame is • Trivia Quiz sound. ISSUE! .-HELLO IT'SUS- / Welcome to It's Onlu Rock and , Muhammad Ali, chicken fried steak, Roll. What are you being welcomed cars with dead batteries, Rocky Hor to anyway? ror Picture Show and working over It's Only Rock and Roll is a time to afford concert tickets and newspaper/magazine of sorts put out vinyl habits. by a few people who know and love Sound comp'iicated, si1ly, insane, music and believe it's time for a unclear? It is all that and more. semi-intelligent, semi-informed rag Best of all it's fun and we' 11 attanpt about music on the local scene. to write about it: show pictures of Because no one is adequately it and make a meager living from it filling the music news and informa as long as it stays complicated, tion void in San Antonio, we decided silly, insane, unclear and fun. -

Gene Pitney, 1940-2006

10 Grapevine GRAPELEAVES Gene Pitney, 1940-2006 Singer/songwriter and News & notes: The James Gang rides Yoakam and others... There are two new Rock And Roll Hall Of again! For the first time in 35 years James titles in Music Video Distributors’ Under Fame member (2002), Gang members Joe Walsh, Jim Fox, and Review series, Velvet Underground, Gene Francis Allan Dale Peters will tour together. The first Under Review and Captain Beefheart, Pitney, age 66, died show kicks off Aug. 9 at Colorado’s Red Under Review. Each DVD features rare unexpectedly of natural Rocks Amphitheatre. Complete tour date performances and interviews along with causes in his Hilton info is available at jamesgang commentary and criticism from band Hotel room April 5, ridesagain.com... This spring will find members and music writers... Other 2006, in Cardiff, Wales. another band on the road for the first time recent DVD releases include Judas He was midway through in many years. Seattle’s Alice In Chains Priest, Live Vengeance ’82. This 17-song www.goldminemag.com GOLDMINE #673 May 12, 2006 • GOLDMINE #673 May www.goldminemag.com a 23-city United members Jerry Cantrell, Mike Inez, and set features the band’s 1982 Memphis, Kingdom tour; he had Sean Kinney haven’t toured together as a Tenn., show ripping out fan faves such just played Cardiff’s St. band since 1996. A re-linked Chains will as “The Hellion/Electric Eye,” “Heading David’s Hall and was hit the stage May 26 at Lisbon, Portugal’s Out To The Highway” and “Hell Bent scheduled to perform Super Bock Festival. -

Dazed N Confused Song List

Dazed n Confused Song List Ozzy Osbourne - Crazy Train - Solo’s, Paranoid 163 Whitesnake - Still of the Night -100 - Solo’s Aerosmith - Walk this Way 109 - Sweet Emotion 99 Uriah Heep - Easy Living 161 Robin Trower - Day of the Eagle 132, No time 127 Joe Walsh - Rocky Mountain Way 83 Molly Hatchet - Dream 106, Flirting w/ Disaster 120 April Wine - Roller 141, Sign of the gypsy queen 138 Rush - Tom Sawyer 175, Limelight 138 Bob Seeger - Strut 116 Ratt - Round and Round solo’s 127, Van Halen - Panama 141, Beautiful Girls 205, Jump 129, Poundcake 105 Thin Lizzy - Jailbreak 145 Rick Derringer - Rock n Roll Hoochie Koo 200 Billy Idol - Rebel Yell 166 Montrose - Space Station #5 168 Led Zeppelin - Immigrant Song 113, (Whole Lotta Love, Bring it on Home, How Many More Times) Foghat - I Just Wanna Make Love to You 127, Slowride 114, Fool for the city 140 Ted Nugent - Stranglehold, Dog Eat Dog 136, Cat Scratch Fever 127 Neil Young - Rockin in the Free World 132 Heart - Barracuda 137 James Gang - Funk 49 91, Walk Away 102 Poison - Nothin But a Good Time 129, Talk Dirty to Me 158 Motley Crue - Mr. Brownstone106, Smokin in the boys room 135, Looks that kill 136, Iron Maiden - Run to the Hills 173 Skid Row - Youth Gone Wild 117 ZZ Top - Tush, Sharped dressed man 125 Scorpions - Rock You Like a Hurricane 126 Grand Funk Railroad - American Band 129 Doucette - Mamma Let Him Play 136 Sammy Hagar - Heavy Metal, There’s only one way to rock 153, I don’t need love 106 Golden Earring - Radar Love -

Doctor Who 4 Ep 17.GREENS

Doctor Who 4 Episode 17 By Russell T Davies Shooting Script GREENS 18th April 2009 Prep starts: 23rd Feb Shooting starts: 30th March Tale Writer's The Doctor Who 4 Episode 17 SHOOTING SCRIPT 20/03/09 page 1 1 FX SHOT - PLANET EARTH 1 FX: THE EARTH, suspended in space, in all its beauty. Over this, the NARRATOR. An old, wise man. NARRATOR It is said that in the final days of Planet Earth, everyone had bad dreams. MIX TO: 2 EXT. SHOPPING STREET - NIGHT 1 2 CAMERA craning down a huge, outdoor CHRISTMAS TREE... NARRATOR To the west of the north of that world, the Human Race did gather, in celebration of a pagan rite, to banish the cold and the dark. ...craning down to find a SALVATION ARMY BRASS BAND. God Rest Ye Merry Gentlemen; the most mournful of carols. Moving round to find a few ONLOOKERS Tale(SHOPPERS in b/g). People, just dotted about, pausing. A woman & gran. Three teenagers. A family, mum, dad and little daughter... NARRATOR (CONT'D) Each and every one of those people had dreamt of the terrible things to come. But they forgot, because they must; they forgot their nightmares, of fire and war and insanity. Writer's They forgot... ...then finding WILFRED MOTT. NARRATOR (CONT'D) TheExcept for one. Wilf's troubled, uneasy, and on his CLOSE UP - INTERCUT, fast, violent - CU of a FACE, bleached, against black - manic laughter - a familiar face, it's - Wilf blinks. Shakes it off. Turns away... CUT TO WIDER. Wilf wandering along. Lost in thought. -

The Relationship Between Fame and Fortune in Performance Related Careers with A

International Journal of Health and Economic Development, 6(2), 36-46, July 2020 36 The Relationship between Fame and Fortune in Performance Related Careers with a Shorter Life Expectancy due to Accidents, Addiction, Homicide and Suicide S. Eric Anderson, Ginny Sim La Sierra University, Riverside, California, USA [email protected] Abstract Around 92% of the US population dies from natural causes. However, only 49% of famous musician stars die from natural causes resulting in performance related careers being one of the most dangerous professions in the United States. According to this study, musicians were 20 times more likely to die from an addiction, four times more likely to die from an accident, six times more likely to die of homicide and four times more likely to die of suicide than the general population. Why do dangerous profession lists fail to include musicians in the high risk career list categories? It is not the profession that is dangerous, but primarily the personality type gravitating towards the profession that creates risk. Should certain personality types be directed to non-performance related careers? Probably not, since performing on stage may be a more effective intervention than psychiatric treatment. Keywords: Accidents, Alcohol, Anxiety, depression, homicide, musicians and suicide. Introduction Is there a relationship between fame in performance related careers with the shorter life expectancy due to accidents, drug overdose, homicide and suicide? The number of musicians, Elvis Presley, Janis Joplin, Jimi Hendrix, Keith Moon, Sid Vicious, Kurt Cobain, Amy International Journal of Health and Economic Development, 6(2), 36-46, July 2020 37 Winehouse, Michael Jackson, Whitney Houston and Prince who died of addiction is staggering. -

Palladia to Exclusively Air 'The Fray: Live in NYC' Saturday, February 14 at 9Pm*

Palladia To Exclusively Air 'The Fray: Live In NYC' Saturday, February 14 at 9pm* NEW YORK, Feb. 11 -- Palladia, MTV Networks' high-definition music channel will exclusively premiere the sold-out performance of the GRAMMY award-nominated band The Fray, in "The Fray: Live In NYC" on Saturday, February 14 at 9pm. The concert which taped on February 4 at Webster Hall in New York City is part of The Rhapsody Rocks concert series and part of VH1 and Rhapsody's ultimate fan sweepstakes for The Fray's new album, The Fray (epic). In the concert, "The Fray: Live In NYC," the band will perform songs from their hit album How To Save A Life and songs from their new self-titled album, The Fray. Songs performed will include "You Found Me," "How To Save A Life," "Over My Head," "Never Say Never" and "Say When" among others. VH1 has also thrown their multiplatform support behind the band with the advance listen program "The Leak" on VH1.com/music which allowed fans to listen to The Fray and buy the album a week in advance of the February 3 release date. The video for "You Found Me" exclusively premiered on VH1's Top 20 Countdown on December 13 and The Fray will appear on a special Top 20 Video Countdown from VH1's Lift Ticket to Ride '09 event on March 14 from Beaver Creek, Colorado. About Palladia Palladia, MTV Networks' high-definition music channel, launched in January 2006 and features original music-based programming for a variety of music genres, including hip hop, rock, country, pop, reggaeton, soul and more, as well as HDTV acquisitions and original content from MTV Networks Music Group's MTV, VH1, and CMT family of services. -

Ramones 2002.Pdf

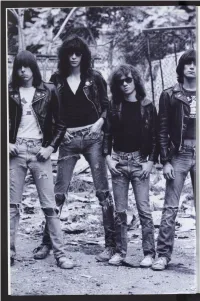

PERFORMERS THE RAMONES B y DR. DONNA GAINES IN THE DARK AGES THAT PRECEDED THE RAMONES, black leather motorcycle jackets and Keds (Ameri fans were shut out, reduced to the role of passive can-made sneakers only), the Ramones incited a spectator. In the early 1970s, boredom inherited the sneering cultural insurrection. In 1976 they re earth: The airwaves were ruled by crotchety old di corded their eponymous first album in seventeen nosaurs; rock & roll had become an alienated labor - days for 16,400. At a time when superstars were rock, detached from its roots. Gone were the sounds demanding upwards of half a million, the Ramones of youthful angst, exuberance, sexuality and misrule. democratized rock & ro|ft|you didn’t need a fat con The spirit of rock & roll was beaten back, the glorious tract, great looks, expensive clothes or the skills of legacy handed down to us in doo-wop, Chuck Berry, Clapton. You just had to follow Joey’s credo: “Do it the British Invasion and surf music lost. If you were from the heart and follow your instincts.” More than an average American kid hanging out in your room twenty-five years later - after the band officially playing guitar, hoping to start a band, how could you broke up - from Old Hanoi to East Berlin, kids in full possibly compete with elaborate guitar solos, expen Ramones regalia incorporate the commando spirit sive equipment and million-dollar stage shows? It all of DIY, do it yourself. seemed out of reach. And then, in 1974, a uniformed According to Joey, the chorus in “Blitzkrieg Bop” - militia burst forth from Forest Hills, Queens, firing a “Hey ho, let’s go” - was “the battle cry that sounded shot heard round the world. -

The Educative Experience of Punk Learners

University of Denver Digital Commons @ DU Electronic Theses and Dissertations Graduate Studies 6-1-2014 "Punk Has Always Been My School": The Educative Experience of Punk Learners Rebekah A. Cordova University of Denver Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.du.edu/etd Part of the Curriculum and Instruction Commons Recommended Citation Cordova, Rebekah A., ""Punk Has Always Been My School": The Educative Experience of Punk Learners" (2014). Electronic Theses and Dissertations. 142. https://digitalcommons.du.edu/etd/142 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate Studies at Digital Commons @ DU. It has been accepted for inclusion in Electronic Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ DU. For more information, please contact [email protected],[email protected]. “Punk Has Always Been My School”: The Educative Experience of Punk Learners __________ A Dissertation Presented to the Faculty of the Morgridge College of Education University of Denver __________ In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy __________ by Rebekah A. Cordova June 2014 Advisor: Dr. Bruce Uhrmacher i ©Copyright by Rebekah A. Cordova 2014 All Rights Reserved ii Author: Rebekah A. Cordova Title: “Punk has always been my school”: The educative experience of punk learners Advisor: Dr. Bruce Uhrmacher Degree Date: June 2014 ABSTRACT Punk music, ideology, and community have been a piece of United States culture since the early-1970s. Although varied scholarship on Punk exists in a variety of disciplines, the educative aspect of Punk engagement, specifically the Do-It-Yourself (DIY) ethos, has yet to be fully explored by the Education discipline. -

Rhino Reissues the Ramones' First Four Albums

2011-07-11 09:13 CEST Rhino Reissues The Ramones’ First Four Albums NOW I WANNA SNIFF SOME WAX Rhino Reissues The Ramones’ First Four Albums Both Versions Available July 19 Hey, ho, let’s go. Rhino celebrates the Ramones’ indelible musical legacy with reissues of the pioneering group’s first four albums on 180-gram vinyl. Ramones, Leave Home, Rocket To Russia and Road To Ruin look amazing and come in accurate reproductions of the original packaging. More importantly, the records sound magnificent and were made using lacquers cut from the original analog masters by Chris Bellman at Bernie Grundman Mastering. For these releases, Rhino will – for the first time ever on vinyl – reissue the first pressing of Leave Home, which includes “Carbona Not Glue,” a track that was replaced with “Sheena Is A Punk Rocker” on all subsequent pressings. Joey, Johnny, Dee Dee and Tommy Ramone. The original line-up – along with Marky Ramone who joined in 1978 – helped blaze a trail more than 30 years ago with this classic four-album run. It’s hard to overstate how influential the group’s signature sound – minimalist rock played at maximum volume – was at the time, and still is today. These four landmark albums – Ramones (1976), Leave Home (1977), Rocket To Russia (1977) and Road to Ruin (1978) – contain such unforgettable songs as: “Blitzkrieg Bop,” “Sheena Is Punk Rocker,” “Beat On The Brat,” “Now I Wanna Sniff Some Glue,” “Pinhead,” “Rockaway Beach” and “I Wanna Be Sedated.” RAMONES Side One Side Two 1. “Blitzkrieg Bop” 1. “Loudmouth” 2. “Beat On The Brat” 2. -

Occupational Therapy Games & Activity List 2019-2020

Occupational Therapy Games & Activity List 2019-2020 Compiled by Stacey Szklut MS, OTR/L & South Shore Therapies Staff Children learn through play and active exploration. The suggestions below may be helpful in choosing appropriate toys for holidays and other special times. They include sensory based activities to provide organizing sensation and encourage the development of body awareness, as well as games to promote eye- hand coordination, visual perception and planning. Approximate ages or skill levels have been given to help guide your choices. Many items can be purchased at toy stores or through the catalogues listed. Ask your occupational therapist for help in deciding which games or toys are the best choices for your child. Games to Develop Coordination, Problem Solving and Visual Perception: Younger Ages (3-6 years) Older Kids (7 and up) Acorn Soup Acuity Ants in the Pants Amazing Labyrinth Game Avalanche Fruit Stand Backseat Drawing Barbecue Party Batik Busytown (by Richard Scarry) Battleship Cat in the Hat I Can Do That! Blink Charades for Kids Blokus Cootie Bounce Off Crazy Cereal Brain vs Brain Puzzle Game (Young Explorers) Crocodile Hop Burger Mania Disney Jr Super Stretchy Game Cheese Louise Don’t Break the Ice Connect Four/ Conniption Don’t Spill the Beans Cover Your Tracks (Thinkfun) Dream Cakes Crab Stack Elefun Cranium Cadoo Elephant Balancing Game Crowded Waters Feed the Woozle Cubeez Frankie’s Food Truck Fiasco Doodle Dice Gobblet Gobblers Doodle Quest Gumball Grab (Lakeshore) Get the Picture Dot-to-Dot Race Hit the Hat Go Go Gelato Honey Bee Tree Guess Who Hungry Hungry Hippos Hang On Harvey I Spy Bingo and Memory Games IQ Fit Journey Through Time Eye Found it! Game Jenga Loopin’ Chewie/Loopin’ Louie Kerplunk/ Tumble Monkeying Around Laser Chess (Thinkfun) Mr. -

Savoy and Regent Label Discography

Discography of the Savoy/Regent and Associated Labels Savoy was formed in Newark New Jersey in 1942 by Herman Lubinsky and Fred Mendelsohn. Lubinsky acquired Mendelsohn’s interest in June 1949. Mendelsohn continued as producer for years afterward. Savoy recorded jazz, R&B, blues, gospel and classical. The head of sales was Hy Siegel. Production was by Ralph Bass, Ozzie Cadena, Leroy Kirkland, Lee Magid, Fred Mendelsohn, Teddy Reig and Gus Statiras. The subsidiary Regent was extablished in 1948. Regent recorded the same types of music that Savoy did but later in its operation it became Savoy’s budget label. The Gospel label was formed in Newark NJ in 1958 and recorded and released gospel music. The Sharp label was formed in Newark NJ in 1959 and released R&B and gospel music. The Dee Gee label was started in Detroit Michigan in 1951 by Dizzy Gillespie and Divid Usher. Dee Gee recorded jazz, R&B, and popular music. The label was acquired by Savoy records in the late 1950’s and moved to Newark NJ. The Signal label was formed in 1956 by Jules Colomby, Harold Goldberg and Don Schlitten in New York City. The label recorded jazz and was acquired by Savoy in the late 1950’s. There were no releases on Signal after being bought by Savoy. The Savoy and associated label discography was compiled using our record collections, Schwann Catalogs from 1949 to 1982, a Phono-Log from 1963. Some album numbers and all unissued album information is from “The Savoy Label Discography” by Michel Ruppli.