The Cinematicity of Literary Cyberpunk on the Example of Neuromancer by William Gibson

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Teaching Speculative Fiction in College: a Pedagogy for Making English Studies Relevant

Georgia State University ScholarWorks @ Georgia State University English Dissertations Department of English Summer 8-7-2012 Teaching Speculative Fiction in College: A Pedagogy for Making English Studies Relevant James H. Shimkus Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.gsu.edu/english_diss Recommended Citation Shimkus, James H., "Teaching Speculative Fiction in College: A Pedagogy for Making English Studies Relevant." Dissertation, Georgia State University, 2012. https://scholarworks.gsu.edu/english_diss/95 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Department of English at ScholarWorks @ Georgia State University. It has been accepted for inclusion in English Dissertations by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks @ Georgia State University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. TEACHING SPECULATIVE FICTION IN COLLEGE: A PEDAGOGY FOR MAKING ENGLISH STUDIES RELEVANT by JAMES HAMMOND SHIMKUS Under the Direction of Dr. Elizabeth Burmester ABSTRACT Speculative fiction (science fiction, fantasy, and horror) has steadily gained popularity both in culture and as a subject for study in college. While many helpful resources on teaching a particular genre or teaching particular texts within a genre exist, college teachers who have not previously taught science fiction, fantasy, or horror will benefit from a broader pedagogical overview of speculative fiction, and that is what this resource provides. Teachers who have previously taught speculative fiction may also benefit from the selection of alternative texts presented here. This resource includes an argument for the consideration of more speculative fiction in college English classes, whether in composition, literature, or creative writing, as well as overviews of the main theoretical discussions and definitions of each genre. -

On Screen Call Me Snake – the Future Noir of Escape from New York

Call Me Snake – The Future Noir Of Escape From New York | Cultured... http://www.culturedeluxe.com/2011/05/call-me-snake-the-future-noir-o... >< Stop Free stuff! IN FOCUS — THE ALIEN SAGA Music reviews Game reviews Movie reviews In print reviews On Screen » In Your Ears » In Digital » In Print » Archive Features » Call Me Snake – The Future Noir Of Escape From New York On Screen May 13, 2011 3 comments » Call Me Snake – The Future Noir Of Escape From New York 3 av 20 2011-10-02 19:50 Call Me Snake – The Future Noir Of Escape From New York | Cultured... http://www.culturedeluxe.com/2011/05/call-me-snake-the-future-noir-o... Share 0 “Down these mean streets a man must go who is not himself mean, who is neither tarnished nor afraid.. he must be the best man in his world.” Raymond Chandler’s words on noir detectives apply as much to Snake Plissken, who, according to writer/ director John Carpenter, is the one man with honour in a world gone mad. And what meaner streets than those of Manhattan Island prison? Escape From New York is ostensibly an action film in a dystopian setting. America and Russia are still engaged in WWIII, while domestically crime has risen 400%. It is implied that the population is gradually going crazy, due to various nerve agents used in the war. To cope with all the crazies, weirdos and violent criminals, Manhattan Island has been turned into one giant prison. Why a prime piece of real estate should be used like this is not made clear, but as a killer concept, it is great. -

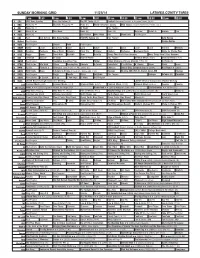

Sunday Morning Grid 11/23/14 Latimes.Com/Tv Times

SUNDAY MORNING GRID 11/23/14 LATIMES.COM/TV TIMES 7 am 7:30 8 am 8:30 9 am 9:30 10 am 10:30 11 am 11:30 12 pm 12:30 2 CBS CBS News Sunday Face the Nation (N) The NFL Today (N) Å Football Cincinnati Bengals at Houston Texans. (N) Å 4 NBC News (N) Å Meet the Press (N) Å News (N) World/Adventure Sports MLS Soccer: Eastern Conference Finals, Leg 1 5 CW News (N) Å In Touch Paid Program 7 ABC News (N) Å This Week News (N) News (N) News Å Vista L.A. Explore Paid 9 KCAL News (N) Joel Osteen Mike Webb Paid Woodlands Paid Program 11 FOX Paid Joel Osteen Fox News Sunday FOX NFL Sunday (N) Paid Program Auto Racing 13 MyNet Paid Program Pirates-Worlds 18 KSCI Paid Program Church Faith Paid Program 22 KWHY Como Local Jesucristo Local Local Gebel Local Local Local Local Transfor. Monkey 24 KVCR Painting Dewberry Joy of Paint Wyland’s Paint This Painting Kitchen Barbecue Heirloom Meals Home for Christy Rost 28 KCET Raggs Space Travel-Kids Biz Kid$ News Asia Biz Things That Aren’t Here Anymore More Things Aren’t Here Anymore 30 ION Jeremiah Youssef In Touch Hour Of Power Paid Program Criminal Minds (TV14) Criminal Minds (TV14) 34 KMEX Paid Program República Deportiva (TVG) Fútbol Fútbol Mexicano Primera División (9:50) (N) Al Punto (N) 40 KTBN Walk in the Win Walk Prince Redemption Liberate In Touch PowerPoint It Is Written B. Conley Super Christ Jesse 46 KFTR Tu Dia Fórmula 1 Fórmula 1 Gran Premio de Abu Dhabi. -

Das Universum Des William Gibson Und Seine Mediale Rezeption“

DIPLOMARBEIT Titel der Diplomarbeit „Das Universum des William Gibson und seine mediale Rezeption“ Verfasser Benjamin Schott angestrebter akademischer Grad Magister der Philosophie (Mag.phil.) Wien, 2013 Studienkennzahl lt. Studienblatt: A 317 Studienrichtung lt. Studienblatt: Theater-, Film- und Medienwissenschaft Betreuer: Ao. Univ.-Prof. Dr. Rainer Maria Köppl Inhaltsverzeichnis 1. Einleitung .............................................................................................................. 4 2. Biografie von William Gibson .............................................................................. 5 3. Das Genre Cyberpunk ......................................................................................... 10 3.1. Die Geschichte des Cyberpunks .................................................................. 10 3.2. Charakteristika ............................................................................................. 14 3.2.1. Postmoderne Zukunft in einem urbanen Handlungsort .................... 15 3.2.2. Einfluss von Technologie auf die menschliche Gesellschaft ............ 16 3.2.3. Verbindung zwischen Mensch und Maschine .................................. 17 3.2.4. Dezentralisierter Zugriff auf Informationen - (Cyberspace, Matrix) .................................................................................................... 18 3.2.5. Globlisierung oder: Die von Konzernen bzw. Organisationen angestrebte Weltherrschaft ............................................ 21 3.2.6. Underground, High-Tech und -

John Carpenter Tribute at the Aero Theater: "Escape from New York" &

John Carpenter Tribute at the Aero Theater: "Escape from New York" &... http://www.associatedcontent.com/article/824127/john_carpenter_tribu... Yahoo! Contributor Network: Sign in Sign up/Publish Community Help The world's largest source of community-created content.™ ENTERTAINMENT AUTO BUSINESS CREATIVE WRITING HEALTH HOME IMPROVEMENT LIFESTYLE NEWS SPORTS TECH TRAVEL BOOKS MOVIES MUSIC ALL CATEGORIES Home » Arts & Entertainment » Movies John Carpenter Tribute at the Aero 1 2 3 The Insiders Guide to Kids Activities in New York Theater: "Escape from New York" City's Bronx Borough & "Escape from LA" Summer Golf Escape Weekend in New York Clint Asay Says "Leave New York City, and Head to The Famed Director Discusses the Adventures of Snake Clint, Michigan" Plissken New York Subway System Flooding Takes New Yorkers-And MTA-"By Surprise" Ben Kenber, Yahoo! Contributor Network Kennedy and The Honorary Title Get Ready to Jun 16, 2008 "Contribute content like this. Start Here." Release New Music to the Masses Q & A with Rising New York DJ, Escape Death Wish Gallagher's Steak House in Las Vegas, Nevada A New York City architect becomes a Cast Members: one-man vigilante squad after his wife Charles Bronson (Paul Kersey) is murdered by street punks in which Hope Lange (Joanna Kersey) he randoml... Vincent Gardenia (Frank Ochoa) Read more » Steven Keats (Jack Toby) William Redfield (Sam Kreutzer) Director: Michael Winner View all » MORE: Escape from New York John Carpenter New Line Cinema Kurt Russell "Escape Artist: A Tribute to John Carpenter" continued Saturday night with the exploits of Snake Plissken who appeared in the double feature "Escape From New York" and "Escape From LA." This again brought the fans out in droves as the Aero Theater in Santa Monica was packed, and the emcee again welcomed us to a showing of "The Happening 2." He said it was a first in that he would show us the M. -

CHOMPING DOWN at SHONEY's ("The Rolls-Royce of Restaurants, Dammit!") Questions by Mike Cheyne

CHOMPING DOWN AT SHONEY'S ("The Rolls-Royce of restaurants, dammit!") Questions by Mike Cheyne General instructions for players and moderators: *A lot of the answerlines here are kind of tricky. I've tried to indicate what's required, what should be prompted on, and when specific terms are required. I can't anticipate everything though, so as a moderator, try and be fairly generous (if a specific term is required, though, that's what is needed for points). *If the answerline requires a film, readers can prompt players who only give partial answers by saying "what film is that in?" For example, if the answerline is something like "the hedge maze in The Shining," and a player only says "the hedge maze," the reader should say "From what film?" in that case. PACKET ONE TU 1. In a film, the wife of a murderous movie theater owner dies because she cannot perform this action, which the Vincent Price-played Dr. Warren Chapin discovers is the only way to stop a parasite present in the bodies of all humans. This action is the only way to stop the title creature in William Castle's film The Tingler. In another movie, fictional director Carl Denham tells one of his performers to do this action "for your life" while they are on an exotic island, marking the first of many times (*) Ann Darrow does this in a 1933 film. Fay Wray's character does this action almost incessantly in the original version of King Kong. For 10 points, name this loud action which actresses in horror movies frequently do. -

BAM Presents John Carpenter: Master of Fear, a Tribute to the Legendary Director and Composer, Feb 5—22

BAM presents John Carpenter: Master of Fear, a tribute to the legendary director and composer, Feb 5—22 Opens with a one-night-only conversation John Carpenter: Lost Themes with Brooke Gladstone Followed by a BAMcinématek retrospective of all of Carpenter’s feature films In conjunction with the release of Carpenter’s debut solo album, Lost Themes, out Feb 3 John Carpenter: Lost Themes with Brooke Gladstone BAM Howard Gilman Opera House (30 Lafayette Ave, Brooklyn) Feb 5 at 8pm Tickets: $25, 35, 50 John Carpenter: Master of Fear film retrospective BAM Rose Cinemas (30 Lafayette Ave, Brooklyn) Feb 6—22 Tickets: $14 general admission, $9 for BAM Cinema Club members Bloomberg Philanthropies is the 2014—2015 Season Sponsor. The Wall Street Journal is the title sponsor for BAM Rose Cinemas and BAMcinématek. Brooklyn, NY/Dec 15, 2014—Renegade auteur John Carpenter makes a rare New York appearance at BAM on Thursday, February 5 to discuss his legendary career and celebrate the release of his first solo album, Lost Themes. Boasting “one of the most consistent and coherent bodies of work in modern cinema” (Kent Jones, Film Comment), Carpenter injects B-movie genres—horror, sci-fi, action—with the bravura stylistic technique of classical Hollywood giants like Howard Hawks, John Ford, and Alfred Hitchcock, and composes the scores for nearly all of his films. He will be joined by Brooke Gladstone, host of NPR’s On the Media, for a wide-ranging discussion of his film and music. Lost Themes will be released in conjunction with the event on February 3 through Sacred Bones Records. -

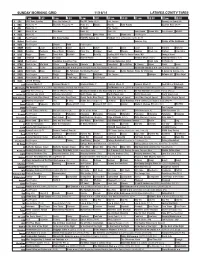

Sunday Morning Grid 11/16/14 Latimes.Com/Tv Times

SUNDAY MORNING GRID 11/16/14 LATIMES.COM/TV TIMES 7 am 7:30 8 am 8:30 9 am 9:30 10 am 10:30 11 am 11:30 12 pm 12:30 2 CBS CBS News Sunday Face the Nation (N) The NFL Today (N) Å Paid Program Courage in Sports (N) 4 NBC News (N) Å Meet the Press (N) Å News (N) Noodle Noodle Auto Racing Spartan Race (N) Å 5 CW News (N) Å In Touch Paid Program 7 ABC News (N) Å This Week News (N) News (N) Jack Hanna Ocean Mys. Sea Rescue Wildlife 9 KCAL News (N) Joel Osteen Mike Webb Paid Woodlands Paid Program 11 FOX Paid Program Fox News Sunday FOX NFL Sunday (N) Football 49ers at New York Giants. (N) Å 13 MyNet Paid Program Veterans Day Pirates of the Caribbean 18 KSCI Paid Program Church Faith Paid Program 22 KWHY Como Local Jesucristo Local Local Gebel Local Local Local Local Transfor. Transfor. 24 KVCR Painting Dewberry Joy of Paint Wyland’s Paint This Painting Cook Mexico Cooking Chefs Life Kitchen Ciao Italia 28 KCET Raggs Space Travel-Kids Biz Kid$ News Asia Biz Healing ADD With Dr. Daniel Amen, MD Younger Heart 30 ION Jeremiah Youssef In Touch Hour Of Power Paid Program Criminal Minds (TV14) Criminal Minds (TV14) 34 KMEX Paid Program República Deportiva (TVG) Premios Bandamax 2014 Hotel Todo Al Punto (N) 40 KTBN Walk in the Win Walk Prince Redemption Liberate In Touch PowerPoint It Is Written B. Conley Super Christ Jesse 46 KFTR Tu Dia Tu Dia Superman Returns ››› (2006) Brandon Routh, Kate Bosworth. -

Snake Plissken Timeline

SnakePlissken.Net - The Definitive Snake Plissken Site file:///C:/Andreas/theefnylapage/articles/timeline.php.htm Snake Plissken Timeline Timeline for Snake Plissken and the Escape Films - Compiled by Sylvia "Swan" Stevens My timeline is consistent with Carpenter's history but I have added details from interviews, from the book, scripts, other 'canon' sources, fleshed out such things as the Summer wars, etc. By 'canon' I mean that the statement was either uttered or written by John Carpenter, Debra Hill, or Kurt Russell in script or interview or recorded in the films or the book. Canon details include the dates and occurrences mentioned in EFLA and EFNY, details of the loss of Snake's eye, the events of Cleveland and Kansas City and the Leningrad Ruse. Extrapolations include precise details of Cleveland and Kansas City dates of Snake's birth and graduations, enlistment and injuries, the abdominal wound and Taylor's presence in Kansas City. It does not contain information from the newly released filmed bank robbery scene as I have not yet seen it. On a parenthetical note: The Purple Heart is NOT a medal for bravery, it is a medal obtained when a person is wounded in the line of duty. The "decorated by the President" would indicate the Congressional Medal of Honor and Carpenter is wrong. Snake cannot be "the youngest man ever decorated" because that honor is already taken historically by a 14 year old drummer boy in (IIRC) the Civil War or the Spanish American war. Also disregarded is the line in EFLA "S.D. "Bob" Plissken!" spoken by the USPF officer. -

Scraping Chunks from the Roof of My Skull with Various November, 2000 CARD NO.1 Phlegmish It Dogs Me, the Phlegm

Clues to the formula: Scraping Chunks What this? Magazine in trading card form. Each pack has 9 cards including from the actual handmade cards, some are screen Roof of My Skull printed this issue. If you should come across this magazine, please read it and then wonder, wonder what. Big fat what. November, Check on line edition for e-resources: Issue No. 3 2000 www.sledbag.com, follow Splooft, Scrape. Editorial Important Situation sorry. Why would I lie? Comment person Because it benefits me and the truth is a rude awakening. Way not ready Words Performance for that. Situation sorry. History Information —Brendan deVallance Ideas Pretty Picture Brendan deVallance [email protected] An End All production, ©2000 An End All production. © 2000 129 Ogden Ave, Jersey City NJ 07307 Pour me Pour me Head case creates the new world in his own image. The sound of it falling is still in my mind. The mess on the floor, a loud amp next to me, and for what I ask you? For what? For all time, that’s what. Oversized cut out hands with chest amplifier. Brendan deVallance Performing at P.S.122 in New York Optimistic (Watered Down) October 16, 1994 On Stage Scraping Chunks from the Roof of My Skull with various November, 2000 CARD NO.1 .2 CARD NO now! sale Phlegmish It dogs me, the phlegm. Poetry never sounded as good as that one word, swear to god. Empty moments are filled with contemplation of this stuff, saliva plus. Drip on tap, top of the world. Phlegm and all of its glory, Set sail for unchartered territories. -

Titles in Comicbase 9 2002 Tokyopop Manga Sampler 2010

Titles in ComicBase 9 2002 Tokyopop Manga Sampler 2010 2020 Visions Titles in blue are new to this edition. 2024 Please see the title notes at the bottom 2099 A.D. of this document for a list of titles that 2099 A.D. Apocalypse have been changed since the previous 2099 A.D. Genesis version. 2099: Manifest Destiny 2099 Special: The World of Doom 100% 2099 Unlimited 1,001 Nights of Bacchus, The 2099: World of Tomorrow 1001 Nights of Sheherazade, The 20 Nude Dancers 20 Year One Poster 100 Bullets Book 100 Degrees in the Shade 20 Nude Dancers 20 Year Two 100 Greatest Marvels of All Time, The 20th Century Eightball 100% Guaranteed How-To Manual 21 for Getting Anyone to Read Comic 2112 (John Byrne’s…) Books!!! (Christa Shermot’s…) 21 Down 100 Pages of Comics 22 Brides 100% True? 24 101 Other Uses For a Condom 2 Fun Flip Book 101 Ways to End the Clone Saga 2-Headed Giant 10th Muse 2 Hot Girls on a Hot Summer Night 10th Muse (Vol. 2) 2 Live Crew Comics 10th Muse/Demonslayer 2 To the Chest 10th Muse Gallery 300 1111 303 13: Assassin Comics Module 30 Days of Night 13 Days of Christmas, The: A Tale of 30 Days of Night: Return to Barrow the Lost Lunar Bestiary 32 Pages 13th of Never, The .357! 1963 39 Screams, The 1984 Magazine 3-D Adventure Comics 1994 Magazine 3-D Alien Terror 1st Folio 3-D Batman 2000 A.D. 3-D-ell 2000 A.D. Extreme Edition 3-D Exotic Beauties 2000 A.D. -

Snake Plissken's 24-Hour Countdown Watch Adds to New Escape from New York Merchandise

Snake Plissken’s 24-Hour Countdown Watch adds to new Escape From New York Merchandise LOS ANGELES, CA - In John Carpenter's classic, “Escape from New York”, Snake Plissken (Kurt Russell), has 24 hours to rescue the President from the country's largest prison, New York City. The United States Police Force gives Snake a gun, a two-way radio and a countdown watch to complete the mission. Ridgewood Watch Company, in partnership with Creative Licensing, has created a reboot, near- replica, version of this watch. The watch has a countdown timer that also displays the time and date, and is a smartwatch that can be paired with an iOS or Android device. The watch is being initially launched on Kickstarter. The campaign is now live and can be viewed here - https://www.kickstarter.com/projects/jonathanzufi/lifeclock-one-the-escape-from-new-york- inspired-sm The watch joins other new Escape from New York Partnerships including. • Cryptozoic Entertainment for board and card games • Silver Fox for collectible statues • Grey Matter for art posters • Bottleneck Gallery for art posters • Boom! Studios for a cross over comic series with “Big Trouble in Little China” The new Boom! Studios comic book cross over between “Escape from New York” and “Big Trouble in Little China” has been widely praised. In fact, John Carpenter in an interview with Greg Pak on Screen Rant said, “..the amazing thing about this is the comic’s style – the drawing style – is hilarious..just this exaggerated Kurt Russell is hilarious to look at. I’m loving it. Just loving it.